Khmer Empire

| Khmer Empire Kambujadesa Kingdom Kampuchea | |||||

| កម្វុជទេឝ | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Yasodharapura Hariharalaya Angkor | ||||

| Languages | Old Khmer Sanskrit | ||||

| Religion | Hinduism Mahayana Buddhism Theravada Buddhism | ||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy | ||||

| King | |||||

| - | 802–850 | Jayavarman II | |||

| - | 1113–1150 | Suryavarman II | |||

| - | 1181–1218 | Jayavarman VII | |||

| - | 1393–1463 | Ponhea Yat | |||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| - | Enthronement of Jayavarman II | 802 | |||

| - | Siamese invasion | 1431 | |||

| Area | |||||

| 1,200,000 km² (463,323 sq mi) | |||||

| Population | |||||

| - | 1150 est. | 4,000,000 | |||

| Today part of | |||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Cambodia |

|

| Early history |

| Dark ages |

| Colonial period |

| Contemporary era |

| Timeline |

| Cambodia portal |

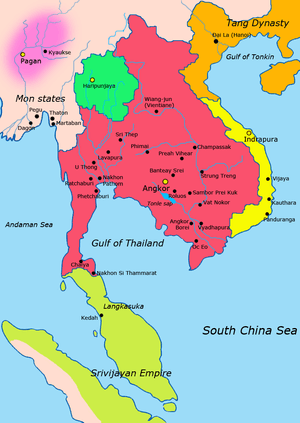

The Khmer Empire (Khmer: ចក្រភពខ្មែរ), now known as Kampuchea,("Srok Khmer" to Khmer people) and Cambodia to the west, was the powerful Khmer Hindu-Buddhist empire in Southeast Asia. The empire, which grew out of the former Kingdom of Funan and Chenla, at times ruled over and/or vassalized most of mainland Southeast Asia, parts of modern-day Laos, Thailand, and southern Vietnam.[1]

Its greatest legacy is Angkor, in present-day Cambodia, which was the site of the capital city during the empire's zenith. The majestic monuments of Angkor — such as Angkor Wat and Bayon — bear testimony to the Khmer empire's immense power and wealth, impressive art and culture, architectural technique and aesthetics achievements, as well as the variety of belief systems that it patronised over time. Recently satellite imaging has revealed Angkor to be the largest pre-industrial urban center in the world.[2]

The beginning of the era of the Khmer Empire is conventionally dated to 802 AD. In this year, king Jayavarman II had himself declared chakravartin ("king of the world", or "king of kings") on Phnom Kulen. The empire ended with the fall of Angkor in the 15th century.

Historiography

The history of Angkor as the central area of settlement of the historical kingdom of Kambujadesa is also the history of the Khmer kingdom from the 9th to the 13th centuries.[3]

From Kambuja itself — and so also from the Angkor region — no written records have survived other than stone inscriptions. Therefore the current knowledge of the historical Khmer civilization is derived primarily from:

- Archaeological excavation, reconstruction and investigation

- Stone inscriptions (most important are foundation steles of temples), which report on the political and religious deeds of the kings

- Reliefs in a series of temple walls with depictions of military marches, life in the palace, market scenes and also the everyday lives of the population

- Reports and chronicles of Chinese diplomats, traders and travellers.

History

Formation and growth

Jayavarman II — the founder of Angkor

According to Sdok Kok Thom inscription, circa 781 Indrapura was the first capital of Jayavarman II, located in Banteay Prei Nokor, near today Kompong Cham.[4] After he eventually returned to his home, the former kingdom of Chenla, he quickly built up his influence, conquered a series of competing kings, and in 790 became king of a kingdom called "Kambuja" by the Khmer. He then moved his court to northwest to Mahendraparvata, far inland north from the great lake of Tonle Sap.

Jayavarman II (r. 790-850) is widely regarded as a king who set the foundations of the Angkor period in Cambodian history, beginning with a grandiose consecration ritual that he conducted in 802 on the sacred Mount Mahendraparvata, now known as Phnom Kulen, to celebrate the independence of Kambuja from Javanese dominion.[5] At that ceremony Prince Jayavarman II was proclaimed a universal monarch (Cambodian: Kamraten jagad ta Raja) or God King (Sanskrit: Deva Raja). He declared himself Chakravartin, in a ritual taken from the Indian-Hindu tradition. Thereby he not only became the divinely appointed and therefore uncontested ruler, but also simultaneously declared the independence of his kingdom from Java. According to some sources, Jayavarman II had resided for some time in Java during the reign of Sailendras, or "The Lords of Mountains", hence the concept of Deva Raja or God King was ostensibly imported from Java. At that time, Sailendras allegedly ruled over Java, Sumatra, the Malay Peninsula and parts of Cambodia,[6] around Mekong delta.

The first pieces of information on Jayavarman II came from K.235 stone inscription on a stele in Sdok Kok Thom temple, Isan region, dating 1053. it recounts two and a half centuries of service that members of the temple's founding family provided for the Khmer court, mainly as chief chaplains of the Shaivite Hindu religion.[7]

According to an older established interpretation, Jayavarman II was supposed to be a prince who lived at the court of Sailendra in Java (today Indonesia) and brought back to his home the art and culture of the Javanese Sailendran court to Cambodia.[8] This classical theory was revisited by modern scholars, such as Claude Jacques[9] and Michael Vickery, who noted that Khmer called chvea the Chams, their close neighbours.[10] Moreover Jayavarman's political career began at Vyadhapura (probably Banteay Prei Nokor) in eastern Cambodia, which make more probable long time contacts with them (even skirmishes, as the inscription suggests) than a long stay in distant Java.[11] Finally, many early temples on Phnom Kulen shows both Cham (e.g. Prasat Damrei Krap) and Javanese influences (e.g. the primitive "temple-mountain" of Aram Rong Cen and Prasat Thmar Dap), even if their asymmetric distribution seems typically khmer.[12]

In the following years he extended his territory and eventually, later in his reign, he moved from Mahendraparvata and established his new capital of Hariharalaya near the modern Cambodian town of Roluos. He thereby laid the foundation of Angkor, which was to arise some 15 km to the northwest. Jayavarman II died in the year 834 and he was succeeded by his son Jayavarman III.[13] Jayavarman III died in 877 and was succeeded by Indravarman I.

The successors of Jayavarman II continually extended the territory of Kambuja. Indravarman I (reigned 877 – 889) managed to expand the kingdom without wars, and he began extensive building projects, thanks to the wealth gained through trade and agriculture. Foremost were the temple of Preah Ko and irrigation works. Indravarman I developed Hariharalaya further by constructed Bakong circa 881. Bakong in particular bears striking similarity to the Borobudur temple in Java, which strongly suggests that it was served as the prototype for Bakong. There must had been exchanges of travelers, if not mission, between Khmer kingdom and the Sailendras in Java. Transmitting to Cambodia not only ideas, but also technical and architectural details.[14]

Yasodharapura — the first city of Angkor

Indravarman I was followed by his son Yasovarman I (reigned 889 – 915), who established a new capital, Yasodharapura – the first city of Angkor. The city's central temple was built on Phnom Bakheng, a hill which rises around 60 m above the plain on which Angkor sits. Under Yasovarman I the East Baray was also created, a massive water reservoir of 7.5 by 1.8 km.

At the beginning of the 10th century the kingdom split. Jayavarman IV established a new capital at Koh Ker, some 100 km northeast of Angkor. Only with Rajendravarman II (reigned 944 – 968) was the royal palace returned to Yasodharapura. He took up again the extensive building schemes of the earlier kings and established a series of temples in the Angkor area, not the least being the East Mebon, on an island in the middle of the East Baray, and several Buddhist temples and monasteries. In 950, the first war took place between Kambuja and the kingdom of Champa to the east (in the modern central Vietnam).

The son of Rajendravarman II, Jayavarman V, reigned from 968 to 1001. After he had established himself as the new king over the other princes, his rule was a largely peaceful period, marked by prosperity and a cultural flowering. He established a new capital slightly west of his father's and named it Jayendranagari; its state temple, Ta Keo, was to the south. At the court of Jayavarman V lived philosophers, scholars, and artists. New temples were also established: the most important of these are Banteay Srei, considered one of the most beautiful and artistic of Angkor, and Ta Keo, the first temple of Angkor built completely of sandstone.

_(6844745654).jpg)

A decade of conflict followed the death of Jayavarman V. Kings reigned for only for a few years and were replaced violently by their successors until Suryavarman I (reigned 1010 – 1050) gained the throne. Suryavarman I established diplomatic relations with the Chola dynasty of south India.[15] Suryavarman I sent a chariot as a present to the Chola Emperor Rajaraja Chola I.[16] His rule was marked by repeated attempts by his opponents to overthrow him and by military conquests. Suryavarman was successful in taking control of the Khmer capital city of Angkor Wat.[17] At the same time, Angkor Wat came into conflict with the Tambralinga kingdom of the Malay peninsula.[17][18] In other words, there was a three-way conflict in mainland Southeast Asia. After surviving several invasions from his enemies, Suryavarman requested aid from the powerful Chola Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty against the Tambralinga kingdom.[17][19][20] After learning of Suryavarman's alliance with Rajendra Chola, the Tambralinga kingdom requested aid from the Srivijaya king Sangrama Vijayatungavarman.[17][18] This eventually led to the Chola Empire coming into conflict with the Srivijiya Empire. The war ended with a victory for the Chola dynasty and of the Khmer Empire, and major losses for the Sri Vijaya Empire and the Tambralinga kingdom.[17][18] This alliance somewhat also has religious nuance, since both Chola and Khmer empire are Hindu Shivaist, while Tambralinga and Srivijaya are Mahayana Buddhist. There is some indication that after these incidents Suryavarman I sent a gift to Rajendra Chola I the Emperor of the Chola Empire to possibly facilitate trade.[21] At Angkor, construction of the West Baray began under Suryavarman I, the second and even larger (8 by 2.2 km) water reservoir after the Eastern Baray. No one knows if he had children or wives.

Golden age

Suryavarman II — Angkor Wat

The 11th century was a time of conflict and brutal power struggles. Under Suryavarman II (reigned 1113–1150) the kingdom united internally and extended externally, and the largest temple of Angkor was built in a period of 37 years: Angkor Wat, dedicated to God Vishnu. Suryavarman II conquered the Mon kingdom of Haripunjaya to the west (in today's central Thailand) and the area farther west to the border with the kingdom of Bagan (modern Burma). In the south he conquered parts of the Malay peninsula down to the kingdom of Grahi (corresponding roughly to the modern Thai province of Nakhon Si Thammarat). In the east several provinces of Champa were added, as well as lands to the north as far as the southern border of modern Laos. Suryavarman II sent a mission to the Chola dynasty of south India and presented a precious stone to the Chola Emperor Kulothunga Chola I in 1114.[22][23] Suryavarman II's end is unclear. The last inscription mentioning his name, in connection with a planned invasion of Vietnam, is from the year 1145. He died during a failed military expedition in Đại Việt territory sometime between 1145 and 1150.

Another period followed in which kings reigned briefly and were violently overthrown by their successors. Finally in 1177 Kambuja was defeated in a naval battle on the Tonlé Sap lake by the army of the Chams and was incorporated as a province of Champa.

Jayavarman VII — Angkor Thom

The future king Jayavarman VII (reigned 1181–1219), generally considered as Cambodian Greatest King, was already a military leader as a prince under previous kings. After the Cham had conquered Angkor, he gathered an army and regained the capital. He attacked his father, believing it was his destiny to be king. He ascended the throne and continued the war against the neighbouring eastern kingdom for another 22 years, until the Khmer defeated Champa in 1203 and conquered large parts of its territory.

Jayavarman VII stands as the last of the great kings of Angkor, not only because of his successful war against the Cham, but also because he was not a tyrannical ruler in the manner of his immediate predecessors. He unified the empire and carried out noteworthy building projects. The new capital, now called Angkor Thom (literally: "Great City"), was built. In the centre, the king (himself a follower of Mahayana Buddhism) had constructed as the state temple the Bayon, with towers bearing faces of the boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara, each several metres high, carved out of stone. Further important temples built under Jayavarman VII were Ta Prohm, Banteay Kdei, and Neak Pean, as well as the reservoir of Srah Srang. An extensive network of roads was laid down connecting every town of the empire, with 121 rest-houses built for traders, officials, and travellers. In addition, he established 102 hospitals.

Jayavarman VII — the last blooming

After the death of Jayavarman VII, his son Indravarman II (reigned 1219–1243) ascended the throne. Like his father, he was a Buddhist, and completed a series of temples begun under his father's rule. As a warrior he was less successful. In the year 1220, under mounting pressure from increasingly powerful Đại Việt, and its Cham alliance, the Khmer withdrew from many of the provinces previously conquered from Champa. aluacqai In the west, his Thai subjects rebelled, established the first Thai kingdom at Sukhothai and pushed back the Khmer. In the following 200 years, the Thais would become the chief rivals of Kambuja.

Indravarman II was succeeded by Jayavarman VIII (reigned 1243–1295). In contrast to his predecessors, Jayavarman VIII was a devotee of the Hindu deity Shiva and an aggressive opponent of Buddhism. He destroyed most of the Buddha statues in the empire (archaeologists estimate the number at over 10,000, of which few traces remain) and converted Buddhist temples to Hindu temples. From the outside, the empire was threatened in 1283 by the Mongols under Kublai Khan's general Sogetu (sometimes known as Sagatu or Sodu), who was the governor of Guangzhou, China.[24] It was a small detachment from the main campaign against Champa and Dai Viet. The king avoided war with his powerful opponent, who at this time ruled over all China, by paying annual tribute to him.[24] Jayavarman VIII's rule ended in 1295 when he was deposed by his son-in-law Srindravarman (reigned 1295–1309). The new king was a follower of Theravada Buddhism, a school of Buddhism that had arrived in southeast Asia from Sri Lanka and subsequently spread through most of the region.

In August 1296, the Chinese diplomat Zhou Daguan arrived at Angkor and remained at the court of king Srindravarman until July 1297. He was neither the first nor the last Chinese representative to visit Kambuja. However, his stay is notable because Zhou Daguan later wrote a detailed report on life in Angkor. His portrayal is today one of the most important sources of understanding historical Angkor. Alongside descriptions of several great temples (the Bayon, the Baphuon, Angkor Wat, for which we have him to thank for the knowledge that the towers of the Bayon were once covered in gold), the text also offers valuable information on the everyday life and the habits of the inhabitants of Angkor.

Decline

After 1327 no further large temples were established. Historians suspect a connection with the kings' adoption of Theravada Buddhism: they were therefore no longer considered "devarajas", and there was no need to erect huge temples to them, or rather to the gods under whose protection they stood. The retreat from the concept of the devaraja may also have led to a loss of royal authority and thereby to a lack of workers. The water-management apparatus also degenerated, meaning that harvests were reduced by floods or drought. While previously three rice harvests per year were possible — a substantial contribution to the prosperity and power of Kambuja — the declining harvests further weakened the empire.

Looking at the archaeological record, however, archaeologists noticed that not only were the structures ceasing to be built, but the Khmer's historical inscription was also lacking from roughly 1300-1600. With this lack of historical content, there is unfortunately very limited archaeological evidence to work with. Archaeologists have been able to determine that the sites were abandoned and then reoccupied later by different individuals.[25]

The western neighbour of the Khmer, the first Thai kingdom of Sukhothai, after repelling Angkorian hegemony, was conquered by another stronger Thai kingdom in the lower Chao Phraya Basin, Ayutthaya, in 1350. From the fourteenth century, Ayutthaya became Angkor's rival. According to its accounts, Ayutthaya launched several attacks. Eventually, it was said, Angkor was subjugated. The Siamese army drew back, leaving Angkor ruled by local nobles, loyal to Ayutthaya. The story of Angkor faded from historical accounts from then on.

There is evidence that the "Black Death" had affected the situation described above, as the plague first appeared in China around 1330 and reached Europe around 1345. Most seaports along the line of travel from China to Europe felt the impact of the disease, which had a severe impact on life throughout South East Asia.

The new centre of the Khmer kingdom was in the southwest, at Oudong in the region of today's Phnom Penh. However, there are indications that Angkor was not completely abandoned. One line of Khmer kings could have remained there, while a second moved to Phnom Penh to establish a parallel kingdom. The final fall of Angkor would then be due to the transfer of economic — and therewith political — significance, as Phnom Penh became an important trade centre on the Mekong. Besides, the severe droughts and ensuing floods were considered as the one of the contributing factors to its fall.[26] The empire focused more on regional trade after the first drought.[27] Overall, climate change, costly construction projects, and conflicts over power between the royal family sealed the end of the Khmer empire.

Ecological failure and infrastructural breakdown is a new alternative theory regarding the end of the Khmer Empire. Scientists working on the Greater Angkor Project believe that the Khmers had an elaborate system of reservoirs and canals used for trade, travel, and irrigation. The canals were used for harvesting rice. As the population grew there was more strain on the water system. During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, there were also severe climatic changes impacting the water management system. Periods of drought led to decreases in agricultural productivity, and violent floods due to monsoons damaged the infrastructure during this vulnerable time.[28] To adapt to the growing population, trees were cut down from the Kulen hills and cleared out for more rice fields. That created rain runoff carrying sediment to the canal network. Any damage to the water system would have enormous consequences.[29]

In any event, there is evidence for a further period of use of Angkor. Under the rule of king Barom Reachea I (reigned 1566–1576), who temporarily succeeded in driving back the Thai, the royal court was briefly returned to Angkor. Inscriptions from the 17th century testify to Japanese settlements alongside those of the remaining Khmer. The best-known inscription tells of Ukondafu Kazufusa, who celebrated the Khmer New Year there in 1632.

For social and religious reasons, many aspects contributed to the decline of the Khmer empire. The relationship between the ruler and their elites was unstable — among the 27 Angkorian rulers, eleven lacked legitimate claim to the power, and civil wars were frequent. The Khmer empire focused more on domestic economy and didn't take advantage of the international maritime network. In addition, the input of Buddhist ideas conflicted and disturbed the state order built under predominately Hinduism religion. [30]

Culture and society

Much of what is known of the ancient Khmer society comes from the many bas-reliefs and also the first-hand Chinese accounts of Zhou Daguan, which provide information on 13th-century Cambodia and earlier. The bas-reliefs of Angkor temples, such as those in Bayon, describe everyday life of the ancient Khmer kingdom, including scenes of palace, naval battles on the river or lakes, and common scenes of the marketplace.

Economy and agriculture

The ancient Khmers were a traditional agricultural community, relying heavily on rice farming. The farmers, who formed the majority of kingdom's population, planted rice near the banks of the lake or river, in the irrigated plains surrounding their villages, or in the hills when lowlands were flooded. The rice paddies were irrigated by a massive and complex hydraulics system, including networks of canals and Barays, or giant water reservoirs. This system enabled the formation of large-scale rice farming communities surrounding Khmer cities. Sugar palm trees, fruit trees, and vegetables were grown in the orchards by the villages, providing other sources of agricultural produce such as palm sugar, palm wine, coconut, various tropical fruits, and vegetables.

Located by the massive Tonlé Sap lake, and also near numerous rivers and ponds, many Khmer people relied on fresh water fisheries for their living. Fishing gave the population their main source of protein, which was turned into Prahok — dried or roasted or steamed fish paste wrapped in banana leaves. Rice was the main staple along with fish. Other source of protein included pigs, cattle, and poultry, which were kept under the farmers' houses that were on stilts to protect them from flooding.

Society and politics

The Khmer empire was founded upon extensive networks of agricultural rice farming communities. A distinct settlement hierarchy is present in the region. Small villages clustered around regional centers, such as the one at Phimai, which in turn sent their goods to large cities like Angkor in return for other goods, such as pottery and foreign trade items from China.[31] The king and his officials were in charge of irrigation management and water distribution, which consisted of an intricate series of hydraulics infrastructure, such as canals, moats, and massive reservoirs called barays. Society was arranged in a hierarchy reflecting the Hindu caste system, where the commoners — rice farmers and fishermen — formed the large majority of the population. The kshatriyas — royalty, nobles, warlords, soldiers, and warriors — formed a governing elite and authorities. Other social classes included brahmins (priests), traders, artisans such as carpenters and stonemasons, potters, metalworkers, goldsmiths, and textile weavers, while on the lowest social level are slaves.

The extensive irrigation projects provided rice surpluses that could support a large population. The state religion was the cult of Devaraja, elevating the Khmer kings as possessing the divine quality of living gods on earth, attributed to the incarnation of Vishnu or Shiva.[32] In politics, this status was viewed as the divine justification of a king's rule. The cult enabled the Khmer kings to embark on massive architectural projects, constructing majestic monuments such as Angkor Wat and Bayon to celebrate the king's divine rule on earth.

Khmer kings were often involved in series of wars and conquests. The large population of Angkor enabled the kingdom to support large free standing armies, which were sometimes deployed to conquer neighboring princedoms or kingdoms. Series of conquests were led to expand the kingdom's influence over areas surrounding Angkor and Tonle Sap, the Mekong valley and delta, and surrounding lands. Some Khmer kings embarked on military conquests and war against neighboring Champa, Dai Viet, and Thai warlords. Khmer kings and royal families were also often involved in incessant power struggle over successions or rivalries over principalities.

Religion

The main religion was Hinduism, followed by Buddhism in popularity. Initially the kingdom revered Hinduism as their main state religion. Vishnu and Shiva were the most revered deities, worshipped in Khmer Hindu temples. Temples such as Angkor Wat are actually known as Preah Pisnulok (Vara Vishnuloka in Sanskrit) or the realm of Vishnu, to honor the posthumous king Suryavarman II as Vishnu.

Hindu ceremonies and rituals performed by brahmins Hindu priests, usually only held among ruling elites of king's family, nobles and the ruling class. The empire's official religions included Hinduism and Mahayana Buddhism, until Theravada Buddhism prevailed, even among the lower classes, after its introduction from Sri Lanka in the 13th century.[33]

Art and architecture

The Khmer empire produced numerous temples and majestic monuments to celebrate the divine authority of Khmer kings. Khmer architecture reflects the Hindu belief that the temple was built to recreate the abode of Hindu gods, Mount Meru, with its five peaks and surrounded by seas represented by ponds and moats. The early Khmer temples built in the Angkor region and the Bakong temple in Hariharalaya (Roluos) employed stepped pyramid structures to represent the sacred temple-mountain.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khmer architecture. |

Khmer art and architecture reached their aesthetic and technical peak with the construction of the majestic temple Angkor Wat. Other temples are also constructed in the Angkor region, such as Ta Phrom and Bayon. The construction of the temple demonstrates the artistic and technical achievements of the Khmer Empire through its architectural mastery of stone masonry.

Culture and way of life

.jpg)

Houses of farmers were situated near the rice paddies on the edge of the cities. The walls of the houses were made of woven bamboo, with thatched roofs, and they were on stilts. A house was divided into three rooms by woven bamboo walls. One was the parents' bedroom, another was the daughters' bedroom, and the largest was the living area. Sons slept wherever they could find space. The kitchen was at the back or in a separate room. Nobles and kings lived in the palace and much larger houses in the city. They were made of the same materials as the farmers' houses, but the roofs were wooden shingles and had elaborate designs as well as more rooms.

The common people wore a sampot where the front end was drawn between the legs and secured at the back by a belt. Nobles and kings wore finer and richer fabrics. Women wore a strip of cloth to cover the chest, while noble women had a lengthened one that went over the shoulder. Men and women wore a Krama. Along with depictions of battle and the military conquests of kings, the bas-reliefs of Bayon depict the mundane everyday life of common Khmer people, including scenes of the marketplace, fishermen, butchers, people playing a chess-like game, and gambling during cockfighting.

Relations with regional powers

During the formation of the empire, the Khmer had close cultural, political, and trade relations with Java,[6] and later with the Srivijaya empire that lay beyond Khmer's southern seas. The Khmer rulers established relations with the Chola dynasty of south India[34] and also China. The empire also was involved in series of wars and rivalries with the neighboring kingdoms of Champa, Tambralinga, Đại Việt, Sukhothai and Ayutthaya.

Arab writers of the 9th and 10th century hardly mention Europe for anything other than its backwardness, but they considered the king of Al-Hind (India and Southeast Asia) as one of the four great kings in the world.[35] The ruler of the Rashtrakuta Dynasty is described as the greatest king of Al-Hind, but even the lesser kings of Al-Hind including the kings of Java, Pagan Burma, and the Khmer kings of Cambodia are invariably depicted by the Arabs as extremely powerful and as being equipped with vast armies of men, horses, and often tens of thousands of elephants. They were also known to have been in possession of vast treasures of gold and silver.[36]

Gallery of temples

- Angkorian Temples in Cambodia

- Angkorian Temples in Thailand

|

|

|

- Angkorian Temples in Laos

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Khmer Empire. |

- Dark ages of Cambodia

- List of kings of Cambodia — Chronological listing with reign, title and posthumous title(s), where known

References

- ↑ infopleace

- ↑ Damian Evans; et al. (2009-04-09). "A comprehensive archaeological map of the world's largest preindustrial settlement complex at Angkor, Cambodia". PNAS 104 (36): 14277–82. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702525104. PMC 1964867. PMID 17717084. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ Thai websites web page

- ↑ Higham 1989, p.324ff

- ↑ Albanese, Marilia (2006). The Treasures of Angkor. Italy: White Star. p. 24. ISBN 88-544-0117-X.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Widyono, Benny (2008). Dancing in shadows: Sihanouk, the Khmer Rouge, and the United Nations in Cambodia. Rowman & Littlefield Publisher. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- ↑ David Chandler, A History of Cambodia (Westview Press: Boulder, Colorado, 2008) p. 39.

- ↑ Coedès, George (1986). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized states of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawai`i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ↑ Jacques, Claude (1972). "La carrière de Jayavarman II". BEFEO (in French) 59: 205–220. ISSN 0336-1519.

- ↑ Vickery, 1998

- ↑ Higham, 2001, pp.53–59

- ↑ Jacques Dumarçay et al. (2001). Cambodian Architecture, Eight to Thirteenth Century. Brill. ISBN 90-04-11346-0. pp.44–47

- ↑ David Chandler, A History of Cambodia, p. 42.

- ↑ David G. Marr, Anthony Crothers Milner (1986). Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th Centuries. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. p. 244. ISBN 9971-988-39-9. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ↑ A History of Early Southeast Asia: Maritime Trade and Societal Development by Kenneth R. Hall p.182

- ↑ Indian History by Reddy: p.64

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Kenneth R. Hall (October 1975), "Khmer Commercial Development and Foreign Contacts under Sūryavarman I", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 18 (3), pp. 318-336, Brill Publishers

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 R. C. Majumdar (1961), "The Overseas Expeditions of King Rājendra Cola", Artibus Asiae 24 (3/4), pp. 338-342, Artibus Asiae Publishers

- ↑ Early kingdoms of the Indonesian archipelago and the Malay Peninsula by Paul Michel Munoz p.158

- ↑ Society and culture: the Asian heritage : by Juan R. Francisco, Ph.D. University of the Philippines Asian Center p.106

- ↑ Economic Development, Integration, and Morality in Asia and the Americas by Donald C. Wood p.176

- ↑ A History of India, Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund: p.125.

- ↑ Commerce and Culture in the Bay of Bengal, 1500-1800 by Om Prakash, Denys Lombard p.29-30

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Cœdès 1966, p. 127

- ↑ Welch, David (1998). "Archaeology of Northeast Thailand in Relation to the Pre-Khmer and Khmer Historical Records". International Journal of Historical Archaeology 2: 205 - 233.

- ↑ Buckley, B. M., Anchukaitis, K. J., Penny, D., Fletcher, R., Cook, E. R., Sano, M., ... & Hong, T. M. (2010). Climate as a contributing factor in the demise of Angkor, Cambodia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(15), 6748-6752.

- ↑ Vickery, M. T. (1977). Cambodia after Angkor: The chronicular evidence for the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries (Vol. 2). Yale University..

- ↑ Buckley, B. M., Anchukaitis, K. J., Penny, D., Fletcher, R., Cook, E. R., Sano, M., ... & Hong, T. M. (2010). Climate as a contributing factor in the demise of Angkor, Cambodia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(15), 6748-6752.

- ↑ Miranda Leitsinger (June 13, 2004). "Scientists dig and fly over Angkor in search of answers to golden city's fall". Associated Press. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ↑ Stark, M. T. (2006). From Funan to Angkor: Collapse and regeneration in ancient Cambodia. After collapse: The regeneration of complex societies, 144-167.

- ↑ Welch, D. J. (1998). Archaeology of northeast Thailand in relation to the pre-Khmer and Khmer historical records. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 2(3), 205-233.

- ↑ Sengupta, Arputha Rani (Ed.) (2005). "God and King : The Devaraja Cult in South Asian Art & Architecture". ISBN 8189233262. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ↑ Keyes, 1995, pp.78–82

- ↑ India: A History by John Keay p.223

- ↑ India and Indonesia During the Ancien Regime: Essays by P. J. Marshall, Robert Van Niel

- ↑ India and Indonesia During the Ancien Regime: Essays by P. J. Marshall, Robert Van Niel: p.41

Bibliography

- Cœdès, George (1966). The making of South East Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-05061-4

- Freeman, Michael; Jacques, Claude (2006). Ancient Angkor. River Books. ISBN 974-8225-27-5.

- Higham, Charles (2001). The Civilization of Angkor. Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-84212-584-7.

- Vittorio Roveda: Khmer Mythology, River Books, ISBN 974-8225-37-2

- Bruno Dagens (engl: Ruth Sharman): Angkor — Heart of an Asian Empire, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-30054-2

- Keyes, Charles F. (1995). The Golden Peninsula. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1696-4.

- Rooney, Dawn F. (2005). Angkor: Cambodia's wondrous khmer temples (5th ed.). Odissey. ISBN 978-962-217-727-7.

- David P. Chandler: A History of Cambodia, Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-3511-6

- Zhou Daguan: The Customs of Cambodia, The Siam Society, ISBN 974-8359-68-9

- Henri Mouhot: Travels in Siam, Cambodia, Laos, and Annam, White Lotus Co, Ltd., ISBN 974-8434-03-6

- Vickery, Michael (1998). Society, economics, and politics in pre-Angkor Cambodia: the 7th–8th centuries. Toyo Bunko. ISBN 978-4-89656-110-4.

- Benjamin Walker, Angkor Empire: A History of the Khmer of Cambodia, Signet Press, Calcutta, 1995.

- I.G. Edmonds, The Khmers of Cambodia:the story of a mysterious people

Coordinates: 13°26′N 103°50′E / 13.433°N 103.833°E

_(6832283873).jpg)

.jpg)

_(6953384297).jpg)

_(6983006145).jpg)