Keyboard technology

Computer keyboards can be classified by the switch technology that they use. Computer alphanumeric keyboards typically have 80–110 durable switches, one for each key. The choice of switch technology affects key response (the positive feedback that a key has been pressed) and travel (the distance needed to push the key to enter a character reliably). Newer keyboard models use hybrids of various technologies to achieve greater cost savings.

Types

Membrane keyboard

There are two types of membrane-based keyboards, flat-panel membrane keyboards and full-travel membrane keyboards:

Flat-panel membrane keyboards are most often found on appliances like microwave ovens or photocopiers. A common design consists of three layers. The top layer (and the one the user touches) has the labels printed on its front and conductive stripes printed on the back. Under this it has a spacer layer, which holds the front and back layer apart so that they do not normally make electrical contact. The back layer has conductive stripes printed perpendicularly to those of the front layer. When placed together, the stripes form a grid. When the user pushes down at a particular position, their finger pushes the front layer down through the spacer layer to close a circuit at one of the intersections of the grid. This indicates to the computer or keyboard control processor that a particular button has been pressed.

Generally, flat-panel membrane keyboards do not produce a noticeable "physical feedback". Therefore, devices using theses issue a beep or flash a light when the key is pressed. They are often used in harsh environments where water- or leak-proofing is desirable. Although used in the early days of the personal computer (on the Sinclair ZX80, ZX81 and Atari 400), they have been supplanted by the more tactile dome and mechanical switch keyboards.

Full-travel membrane-based keyboards are the most common computer keyboards today. They have one-piece plastic keytop/switch plungers which press down on a membrane to actuate a contact in an electrical switch matrix.

Dome-switch keyboard

Dome-switch keyboards are a hybrid of flat-panel membrane and mechanical-switch keyboards. They bring two circuit board traces together under a rubber or silicone keypad using either metal "dome" switches or polyurethane formed domes. The metal dome switches are formed pieces of stainless steel that, when compressed, give the user a crisp, positive tactile feedback. These metal types of dome switches are very common, are usually reliable to over 5 million cycles, and can be plated in either nickel, silver or gold. The rubber dome switches, most commonly referred to as polydomes, are formed polyurethane domes where the inside bubble is coated in graphite. While polydomes are typically cheaper than metal domes, they lack the crisp snap of the metal domes, and usually have a lower life specification. Polydomes are considered very quiet, but purists tend to find them "mushy" because the collapsing dome does not provide as much positive response as metal domes. For either metal or polydomes, when a key is pressed, it collapses the dome, which connects the two circuit traces and completes the connection to enter the character. The pattern on the PC board is often gold-plated.

Both are common switch technologies used in mass market keyboards today. This type of switch technology happens to be most commonly used in handheld controllers, mobile phones, automotive, consumer electronics and medical devices. Dome-switch keyboards are also called direct-switch keyboards.

See also: Chiclet keyboard

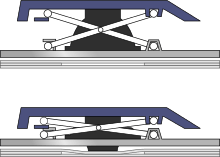

Scissor-switch keyboard

A special case of the computer keyboard dome-switch is the scissor-switch. The keys are attached to the keyboard via two plastic pieces that interlock in a "scissor"-like fashion, and snap to the keyboard and the key. It still uses rubber domes, but a special plastic 'scissors' mechanism links the keycap to a plunger that depresses the rubber dome with a much shorter travel than the typical rubber dome keyboard. Typically scissor-switch keyboards also employ 3-layer membranes as the electrical component of the switch. They also usually have a shorter total key travel distance (2 mm instead of 3.5 – 4 mm for standard dome-switch keyswitches). This type of keyswitch is often found on the built-in keyboards on laptops and keyboards marketed as 'low-profile'. These keyboards are generally quiet and the keys require little force to press.

Scissor-switch keyboards are typically slightly more expensive. They are harder to clean (due to the limited movement of the keys and their multiple attachment points) but also less likely to get debris in them as the gaps between the keys are often less (as there is no need for extra room to allow for the 'wiggle' in the key as you would find on a membrane keyboard).[1]

Capacitive keyboard

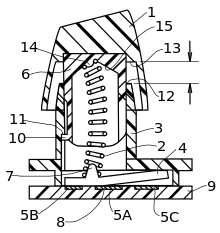

In this type of keyboard, pressing the key changes the capacitance of a pattern of capacitor pads. Unlike "dome switch" keyboards, the pattern consists of two D-shaped capacitor pads for each switch, printed on a printed circuit board (PCB) and covered by a thin, insulating film of soldermask which plays the role of a dielectric. The mechanism of capacitive switches is very simple, compared to mechanical ones. Its movable part is ended with a flat foam element (of dimensions near to a tablet of Aspirin) finished with aluminium foil below. The opposite side of the switch is a PCB with the capacitor pads.

When a key is pressed, the foil tightly clings to the surface of the PCB, forming a daisy chain of two capacitors between contact pads and itself separated with thin soldermask, and thus "shorting" the contact pads with an easily detectable drop of capacitive reactance between them. Usually this permits a pulse or pulse train to be sensed. The keys do not need to be fully pressed to be fired on, which enables some typists to work faster.

Mechanical-switch keyboard

Mechanical-switch keyboards use separate complete switches underneath every key. Each switch is composed of a base, a spring, and a stem. Depending on the shape of the stem, such keyboards have varying actuation and travel distance. Depending on the resistance of the spring, the key requires different amounts of pressure to actuate. Mechanical keyboards allow for the removal and replacement of keycaps.

The major mechanical switch producers are Cherry and Alps Electric. Companies such as Cooler Master, Corsair, Razer, Thermaltake, Logitech and SteelSeries offer a variety of mechanical model keyboards targeted towards gamers.

Buckling-spring keyboard

Many typists prefer buckling spring keyboards.[2] The buckling spring mechanism (expired U.S. Patent 4,118,611) atop the switch is responsible for the tactile and aural response of the keyboard. This mechanism controls a small hammer that strikes a capacitive or membrane switch.[3]

In 1993, two years after spawning Lexmark, IBM transferred its keyboard operations to the daughter company. New Model M keyboards continued to be manufactured for IBM by Lexmark until 1996, when Unicomp purchased the keyboard technology.

Today, new buckling-spring keyboards are manufactured by Unicomp. Unicomp also repairs old IBM and Lexmark keyboards.

Hall-effect keyboard

Hall effect keyboards use magnets and Hall effect sensors instead of an actual switch. When a key is depressed, it moves a magnet, which is detected by the solid-state sensor. These keyboards are extremely reliable, and can accept millions of keystrokes before failing. They are used for ultra-high reliability applications, in locations like nuclear powerplants or aircraft cockpits. They are also sometimes used in industrial environments. These keyboards can be easily made totally waterproof. They also resist large amounts of dust and contaminants. Because a magnet and sensor are required for each key, as well as custom control electronics, they are very expensive.

Laser keyboard

A laser projection device approximately the size of a computer mouse projects the outline of keyboard keys onto a flat surface, such as a table or desk. This type of keyboard is portable enough to be easily used with PDAs and cellphones, and many models have retractable cords and wireless capabilities. However, sudden or accidental disruption of the laser will register unwanted keystrokes. Also, if the laser malfunctions, the whole unit becomes useless, unlike conventional keyboards which can be used even if a variety of parts (such as the keycaps) are removed. This type of keyboard can be frustrating to use since it is susceptible to errors, even in the course of normal typing, and its complete lack of tactile feedback makes it even less user-friendly than the lowest quality membrane keyboards.

Roll-up keyboard

Keyboards made of flexible silicone or polyurethane materials can roll up in a moderately tight bundle. Tightly folding the keyboard may damage the internal membrane circuits. When they are completely sealed in rubber they are water resistant. Like membrane keyboards, they are reported to be very hard to get used to, as there is little tactile feedback, and silicone will tend to attract dirt, dust, and hair.

See Roll-away computer.

Optical keyboard technology

Also known as photo-optical keyboard, light responsive keyboard, photo-electric keyboard, and optical key actuation detection technology.

Optical keyboard technology was introduced in 1962 by Harley E. Kelchner for use in a typewriter machine with the purpose of reducing the noise generating by actuating the typewriter keys.

An optical keyboard technology utilizes light-emitting devices and photo sensors to optically detect actuated keys. Most commonly the emitters and sensors are located at the perimeter, mounted on a small PCB. The light is directed from side to side of the keyboard interior, and it can only be blocked by the actuated keys. Most optical keyboards require at least 2 beams (most commonly a vertical beam and a horizontal beam) to determine the actuated key. Some optical keyboards use a special key structure that blocks the light in a certain pattern, allowing only one beam per row of keys (most commonly a horizontal beam).

The mechanism of the optical keyboard is very simple – a light beam is sent from the emitter to the receiving sensor, and the actuated key blocks, reflects, refracts or otherwise interacts with the beam, resulting in an identified key.

Some earlier optical keyboards were limited in their structure and required special casing to block external light, no multi-key functionality was supported and the design was very limited to a thick rectangular case.

The advantages of optical keyboard technology are that it offers a real waterproof keyboard, resilient to dust and liquids; and it uses about 20% PCB volume, compared with membrane or dome switch keyboards, significantly reducing electronic waste. Additional advantages of optical keyboard technology over other keyboard technologies such as Hall effect, laser, roll-up, and transparent keyboards lie in cost (Hall effect keyboard) and feel – optical keyboard technology does not require different key mechanisms, and the tactile feel of typing has remained the same for over 60 years.

The specialist Datahand keyboard uses optical technology to sense keypresses with a single light beam and sensor per key. The keys are held in their rest position by magnets; when the magnetic force is overcome to press a key, the optical path is unblocked and the keypress is registered.

Debouncing

When striking a keyboard key, the key oscillates (or bounces) against its contacts several times before settling. When released, it oscillates again until it reverts to its rest state. Although it happens on such a small scale as to be invisible to the naked eye, it's sufficient for the computer to register multiple key strokes inadvertently.

To resolve this problem, the processor in a keyboard "debounces" the keystrokes, by aggregating them across time to produce one "confirmed" keystroke that (usually) corresponds to what is typically a solid contact. Early membrane keyboards had limited typing speed because they had to do significant debouncing. This was a noticeable problem on the ZX81.

Keytops

Keytops are used on full-travel keyboards. While modern keycaps are typically surface-printed, they can also be 2-shot molded, laser printed, sublimation printed, engraved, or they can be made of transparent material with printed paper inserts.

There are also Keycaps, which are thin shells that are placed over keytop bases. These were used on IBM PC keyboards.

Other parts of the PC keyboard

The modern PC keyboard also includes a control processor and indicator lights to provide feedback to the user about what state the keyboard is in. Depending on the sophistication of the controller's programming, the keyboard may also offer other special features. The processor is usually a single chip 8048 microcontroller variant. The keyboard switch matrix is wired to its inputs and it processes the incoming keystrokes and sends the results down a serial cable (the keyboard cord) to a receiver in the main computer box. It also controls the illumination of the "caps lock", "num lock" and "scroll lock" lights.

A common test for whether the computer has crashed is pressing the "caps lock" key. The keyboard sends the key code to the keyboard driver running in the main computer; if the main computer is operating, it commands the light to turn on. All the other indicator lights work in a similar way. The keyboard driver also tracks the shift, alt and control state of the keyboard.

Keyboard switch matrix

The keyboard switch matrix is often drawn with horizontal wires and vertical wires in a grid which is called a matrix circuit. It has a switch at some or all intersections, much like a multiplexed display. Almost all keyboards have only the switch at each intersection, which causes "ghost keys" and "key jamming" when multiple keys are pressed (rollover). Certain, often more expensive, keyboards have a diode between each intersection, allowing the keyboard microcontroller to accurately sense any number of simultaneous keys being pressed, without generating erroneous ghost keys.[4]

References

- ↑ "Mechanical vs membrane keyswitches", Keyboards, CA: Ergo.

- ↑ "IBM 42H1292 and 1391401 keyboards", Dan's Data (review), 13 Nov 2007 [15 August 1999]

- ↑ "Tech: buckling spring", Qwerters Clini, Wakwak.

- ↑ Dribin, Dave. "Keyboard Matrix Help".

External links

- Taking apart a dome-switch keyboard, Wei Wong.