Kate Shelley

Catherine Carroll "Kate" Shelley (December 12, 1863 – January 21, 1912[1]) was a midwestern United States railroad heroine, and the first woman in the United States to have a bridge named for her. She was also one of the few women to ever have a train named after her, the Kate Shelley 400.[2]

Background

Kate Shelley was born at Loughaun, a crossroads near the village of Dunkerrin and the town of Moneygall, in County Offaly, Ireland.[3] Dunkerrin Catholic Church records show that her parents, Michael Shelly and Margaret Dwan, married on February 24, 1863, and Catherine was baptized on December 12, 1863. Her tombstone says she was born on September 25, 1865 and died January 21, 1912. The family name was originally spelled Shelly, which is how Kate wrote her name, but the spelling Shelley was later adopted.[4]

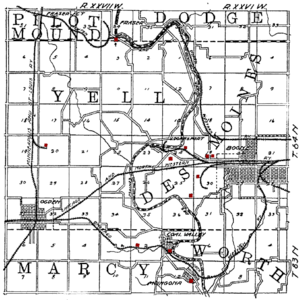

Michael Shelley was likely a tenant farmer in Ireland. The family emigrated to the United States when Catherine was a baby.[3] They first lived with relatives in Freeport, Illinois, then built a home on 160 acres (0.65 km2) at Honey Creek, near Moingona, Boone County, Iowa.[3] Michael Shelley became foreman of a section crew, building tracks for the Chicago and North Western Railway.[3]

Michael Shelley died of "consumption," the name for what was later identified as tuberculosis, in 1878. Kate had to help support the family by plowing, planting and harvesting crops, and hunting.[3] The 1880 federal census for Worth Township, Boone County, Iowa showed 35-year old Margaret, 15-year-old Kate, both born in Ireland, and Mary (8), Margaret (6) and John (4), all born in Iowa.[5] Michael and Margaret Shelley had another child, James (also born in Iowa), but he drowned while swimming in the Des Moines River when he was only ten years old.[6]

The story

On the afternoon of July 6, 1881, heavy thunderstorms caused a flash flood of Honey Creek, washing out timbers that supported the railroad trestle. A pusher locomotive sent from Moingona to check track conditions crossed the Des Moines River bridge, but plunged into Honey Creek when the bridge fell away at about 11 p.m., with a crew of four: Ed Wood, A.P. Olmstead, Adam Agar and Patrick Donahue.[7]

Kate Shelley heard the crash, and knew an eastbound passenger train was due in Moingona about midnight, stopping shortly before heading east over the Des Moines River and then Honey Creek. She found the surviving crew members and shouted that she would get help, then started to cross the damaged span of the Honey Creek bridge followed by the Des Moines River bridge. Although she'd started with a lantern, it had failed, and she crawled the span on hands and knees with only lightning for illumination. Once across, she ran a half-mile to the Moingona depot to sound the alarm, then led a party back to rescue two of the engine crew survivors.[7] Wood, perched in a tree, grasped a rope thrown to him, and came ashore hand-over-hand.[8] Agar couldn't be reached until the flood waters began to recede.[8] Donahue's corpse was eventually found in a cornfield a quarter mile downstream from the bridge, but Olmstead, the fireman, was never found. The passenger train was stopped at Ogden, Iowa, with 200 aboard.[3]

The aftermath

The passengers who had been saved took up a collection for her. The children of Dubuque gave her a medal,[7] and the state of Iowa gave her another one, crafted by Tiffany & Co.,[9] and $200.[7] The C&NW gave her $100, a half barrel of flour, half a load of coal and a life-time pass.[7] The Order of Railway Conductors gave her a gold watch and chain.[7]

News of her bravery spread nationwide; poems and songs were composed honoring her. The Chicago & Northwestern Railroad built a new steel bridge in 1901 and named it the Boone Viaduct, but people quickly nicknamed it the Kate Shelley Bridge or Kate Shelley High Bridge.[10] It was the first and, until the Betsy Ross Bridge in Philadelphia was opened in 1976, the only bridge in the United States named for a woman. A second bridge was built alongside the old by the Union Pacific Railroad from 2006 through 2009. The new structure can accommodate heavy trains, features two tracks and can handle two trains simultaneously at a speed of 70 mph. It was opened on October 1, 2009 as the new Kate Shelley Bridge, one of North America's tallest double-track rail bridges.

Frances E. Willard, a reformer and temperance leader, wrote her friend, Isabella W. Parks, who was the wife of the president of Simpson College at Indianola, Iowa, offering $25 toward an advanced education for Kate Shelley. Mrs. Parks raised additional funds for Kate Shelley to attend during the term of 1883–84, but she didn't come back the following term.[7]

Later in life

In 1890, the Chicago Tribune revealed that the Shelley home was mortgaged for $500 at 10% and was near foreclosure. An Armenian rug, woven in the display window of a Chicago furniture store, was auctioned for $500, retiring the mortgage, and other Chicagoans donated an additional $417.[7]

In July 1896, it was reported that Shelley had applied to the Iowa Legislature for employment in the State House as a menial, because she was destitute and had to support her mother and invalid brother.[11] She did work at the Iowa Capitol more than once, but the rumor of an invalid brother was untrue, as her surviving brother worked for the Chicago & North Western Railroad for most of his life.

Although there were apparently men interested in her, supposedly including the switchman in the yard at Moingona,[12] Kate Shelley never married and lived with her mother and sister Mary or "Mayme" (pronounced "maim") until their mother died in 1909.[7]

Kate Shelley held many odd jobs, including that of teacher in Boone County, until 1903, when the Chicago & North Western gave her the job of station agent at the new Moingona depot,[13] the old depot having burned down in 1901.[14]

In 1910, Kate's health began to decline. In June 1911, doctors at Carroll Hospital removed her appendix. After more than a month in the hospital, she returned to Boone and stayed with her brother John.[14] She was reported to be a little better by September, but she died on January 12, 1912 from Bright's disease (acute nephritis).[15]

Years later, the Chicago and North Western began operating streamlined passenger trains, and named one the Kate Shelley 400. It operated from 1955 to 1971, although the name was officially dropped in 1963.[2]

Legacy

The Boone County Historical Society maintains the Kate Shelley Railroad Museum on the site of the Moingona depot. The Shelley family donated a collection of letters and papers of family members of Kate Shelley, 1860–1911, to Iowa State University. The timetable accents for Metra's Union Pacific/West Line are printed in "Kate Shelley Rose" pink.[16]

The original high steel bridge nicknamed the Kate Shelley High Bridge (officially called the Boone Viaduct) still stands. In 2009, the Union Pacific Railroad completed a new concrete and steel bridge next to the Boone Viaduct and christened the new one the Kate Shelley Bridge.

The Iowa poet and politician, John Brayshaw Kaye, wrote a poem in her honor called, 'Our Kate', in his collection Songs of Lake Geneva (1882).[17]

Margaret Wetterer wrote a children's book called "Kate Shelley and the Midnight Express" in 1991 telling the story of Kate Shelley, a book which was featured in an episode of the children's television program Reading Rainbow.

References

- ↑ http://www.kateshelley.com/about-kate.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Scribbins, Jim (2008) [1982]. The 400 Story. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816654499. OCLC 191760067.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Irish Midland Ancestry

- ↑ Kate Shelley: Railway Heroine

- ↑ U.S. Census Year: 1880; Census Place: Worth, Boone, Iowa; Roll: T9_328; Family History Film: 1254328; Page: 155.1000; Enumeration District: 10; Image: 0394.

- ↑ Boone County Republican, July 16, 1879

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Kate Shelley story

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 The Kate Shelley Story

- ↑ Burlington Hawkeye, Burlington, Des Moines, Iowa March 30, 1882

- ↑ Kate Shelley bridge

- ↑ The Batavia [Illinois] Herald, 22 July 1896

- ↑ Burlington Hawkeye, May 4, 1882

- ↑ Daily Iowa State Press Iowa City, Johnson, Iowa October 17, 1903

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kate Shelley, Railroader

- ↑ Washington Post, January 22, 1912

- ↑ "Did you know?". On the Bi-Level: 3. June 2009.

- ↑ Songs of Lake Geneva (1882) and other poems, G.P.Putnam's Sons, New York

External links

- http://www.kateshelley.com Kate Shelley, Heroine of the High Bridge