Kashubians

|

Flag and coat of arms of Kashubia | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~ 500,000 (2002)[1] of which 233,000[2] as nationality (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

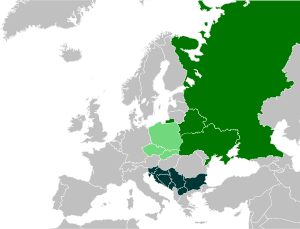

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Kashubian, Polish, among emigrants English, German | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Poles · Slovincians · Sorbs |

Kashubians (Kashubian: Kaszëbi; Polish: Kaszubi; German: Kaschuben) also spelled as Kaszubians, Kassubians, Cassubians, Cashubes or Kashubs, and formerly known as Kashubes,[3] are a West Slavic ethnic group[4] in Pomerelia, north-central Poland. Their settlement area is referred to as Kashubia (Kashubian: Kaszëbë, Polish: Kaszuby, German: Kaschubei, Kaschubien). They speak the Kashubian language, classified either as a separate language or a Polish dialect.[5][6] In analogy to the linguistic classification, Kashubians are considered either an ethnic or a linguistic group.[6] Kashubians are closely related to Poles and their language is, even if considered a separate language, closely related to Polish.

Kashubians are grouped with the Slovincians as Pomeranians. Similarly the Slovincian and Kashubian languages are grouped as the Pomeranian language, with Slovincian being either a closely related language[7] or a Kashubian dialect.[8][9]

Modern Kashubia

Among larger cities, Gdynia (Gdiniô) contains the largest proportion of people declaring Kashubian origin. However, the biggest city of the Kashubia region is Gdańsk (Gduńsk), the capital of the Pomeranian Voivodeship and the traditional capital of Kashubia. Between 80.3% and 93.9% people of the people in Linia, Sierakowice, Szemud, Kartuzy, Chmielno, Żukowo, etc. are of Kashubian descent.[10]

The traditional occupations of Kashubians have been agriculture and fishing. These have been joined by the service and hospitality industries, as well as agrotourism. The main organization that maintains the Kashubian identity is the Kashubian-Pomeranian Association. The recently formed "Odroda" is also dedicated to the renewal of Kashubian culture.

The traditional capital has been disputed for a long time and includes Kartuzy (Kartuzë) among the seven contenders.[11] The biggest cities claiming to be the capital are: Gdańsk (Gduńsk),[12] Wejherowo (Wejrowò),[13] and Bytów (Bëtowò).[14][15]

Population

The total number of Kashubians varies depending on one's definition. A common estimate is that over 300,000 people in Poland are of the Kashubian ethnicity. The most extreme estimates are as low as 50,000 or as high as 500,000. In the Polish census of 2002, only 5,100 people declared Kashubian nationality, although 51,000 declared Kashubian as their native language. Most Kashubians declare Polish nationality and Kashubian ethnicity, and are considered both Polish and Kashubian. However, on the 2002 census there was no option to declare one nationality and a different ethnicity, or more than one nationality. At the 2011 census however, the number of persons declaring "Kashubian" as their only identity was 16,000, and 233,000 including those who declared Kashubian as first or second ethnicity.[2]

History

Kashubs are a Slavic people living on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Studies have shown that Kashubs are the remnant of the Medieval Pomeranian people which arrived in Pomerania prior to the arrival of the Poles.

Kashubs have their own language and traditions, having lived somewhat isolated for centuries. They have natural claims to the territory which they occupy, as it has been their home from remote ages. They founded the city of Gdańsk.

Origin

Kashubians descend from the Slavic Pomeranian tribes, who had settled between the Oder and Vistula Rivers after the Migration Period, and were at various times Polish and Danish vassals. While most Slavic Pomeranians were assimilated during the medieval German settlement of Pomerania (Ostsiedlung), especially in the Pomeranian Southeast (Pomerelia) some kept and developed their customs and became known as Kashubians. The oldest known mention of "Kashubia" dates from 19 March 1238 – Pope Gregor IX wrote about Bogislaw I dux Cassubie – the Duke of Kashubia. The old one dates from the 13th century (a seal of Barnim I from the House of Pomerania, Duke of Pomerania-Stettin). The Dukes of Pomerania hence used "Duke of (the) Kashubia(ns)" in their titles, passing it to the Swedish Crown who succeeded in Swedish Pomerania when the House of Pomerania became extinct.

Administrative history of Kashubia

The westernmost (Slovincian) parts of Kashubia, located in the medieval Lands of Schlawe and Stolp and Lauenburg and Bütow Land, were integrated into the Duchy of Pomerania in 1317 and 1455, respectively, and remained with its successors (Brandenburgian Pomerania and Prussian Pomerania) until 1945, when the area became Polish. The bulk of Kashubia since the 12th century was within the medieval Pomerelian duchies, since 1308 in the Monastic state of the Teutonic Knights, since 1466 within Royal Prussia, an autonomous territory of the Polish Crown, since 1772 within West Prussia, a Prussian province, since 1920 within the Polish Corridor of the Second Polish Republic, since 1939 within the Reichsgau Danzig-West Prussia of Nazi Germany, and since 1945 within the People's Republic of Poland, and after within the Third Polish Republic.

German and Polish impact

German Ostsiedlung in Kashubia was first initiated by the Pomerelian dukes[16] and focussed on the towns, whereas much of the countryside remained Kashubian.[17] An exception was the German settled Vistula delta[17] (Vistula Germans), the coastal regions,[16] and the Vistula valley.[16] Following the centuries of interaction between local German and Kashubian population, Aleksander Hilferding (1862) and Alfons Parczewski (1896) confirmed a progressive language shift in the Kashubian population from their Slavonic vernacular to the local German dialect (Low German Ostpommersch, Low German Low Prussian, or High German).[7]

On the other hand, Pomerelia since the Middle Ages was assigned to the Kuyavian Diocese of Leslau and thus retained Polish as the church language. Only the Slovincians in 1534 adopted Lutheranism after the Protestant Reformation had reached the Duchy of Pomerania,[18][19][20] while the Kashubes in Pomerelia remained Roman Catholic. The Prussian parliament (Landtag) in Königsberg changed the official church language from Polish to German in 1843, but this decision was soon repealed.

In the 19th century the Kashubian activist Florian Ceynowa undertook efforts to identify the Kashubian language, and its culture and traditions. He awakened Kashubian self-identity, thereby opposing both Germanisation and Prussian authority, and Polish nobility and clergy.[21] He believed in a separate Kashubian identity and strove for a Russian-led pan-Slavic federacy,[21] He considered Poles "born brothers".[22] Ceynowa attempted to take the Prussian garrison in Preußisch Stargard (Starogard Gdański) during 1846,[23] but the operation failed when his 100 combatants, armed only with scythes, decided to abandon the site before the attack was carried out.[24] Some later Kashubian activists rejected the idea of a separate Kashub nation and considered themselves a unique branch of the Polish nation, manifested in the words of Kashubian journalist and activist Hieronim Derdowski "There is no Cassubia without Poland, and no Poland without Cassubia" (Nie ma Kaszeb bez Polski a bez Kaszeb Polski").[22] The Society of Young Kashubians (Towarzystwo Młodokaszubskie) has decided to follow in this way, and while they the sought to create a strong Kashubian identity, at the same time saw in Kashubs "One branch, of many, of the great Polish nation".[22]

The leader of the movement was Aleksander Majkowski, a doctor educated in Chełmno thanks to the Society of Educational Help in Chełmno. In 1912 he founded the Society of Young Kashubians and started the newspaper "Gryf". Kashubs voted for Polish lists in elections, which strengthened the representation of Poles in the Pomerania region.[22][25][26][27][28]

Due to their Catholic faith, the Kashubians were subject to Prussia's Kulturkampf in the late 19th century.[29] The Kashubians faced Germanification efforts, including those by evangelical Lutheran clergy. These efforts were successful in Lauenburg (Lębork) and Leba (Łeba), where the local population used the Gothic alphabet.[22] While resenting the disrespect shown by some Prussian officials and junkers, Kashubians lived in peaceful coexistence with the local German population until World War II, although during the interbellum, the Kashubian ties to Poland were either overemphasized or neglected by Polish and German authors, respectively, in arguments regarding the Polish Corridor.[29]

During the Second World War, Kashubians were considered by the Nazis as being either of "German stock" or "extraction", or "inclined toward Germanness" and "capable of Germanisation", and thus classified third category of Deutsche Volksliste (German ethnic classification list) if possible ties to the Polish nation could be dissolved.[30] However, Kashubians who were suspected to support the Polish cause,[29] particularly those with higher education,[29] were arrested and executed, the main place of executions being Piaśnica (Groß Plaßnitz),[31] where 12,000 were executed.[32][33] The German administrator of the area Albert Forster considered Kashubians of "low value" and didn't support any attempts to create Kashubian nationality.[34] Some Kashubians organized anti-Nazi resistance groups, "Gryf Kaszubski" (later "Gryf Pomorski"), and the exiled "Zwiazek Pomorski" in Great Britain.[29]

When integrated into Poland, those envisioning Kashubian autonomy faced a Communist regime striving for ethnic homogeneity and presenting Kashubian culture as merely folklore.[29] Kashubians were sent to Silesian mines, where they met Silesians facing similar problems.[29] Lech Bądkowski from the Kashubian opposition became the first spokesperson of Solidarność.[29]

Language

In 2011 Population Census about 108,100 Kashubians declares Kashubian as their language.[35]

The classification of Kashubian as a language or dialect has been controversial.[6] From a diachronic point of view of historical linguistics, Kashubian like Slovincian, Polabian and Polish is a Lechitic West Slavic language, while from a synchronic point of view it is a group of Polish dialects.[6] Given the past nationalist interests of Germans and Poles in Kashubia, Barbour and Carmichel state: "As is always the case with the division of a dialect continuum into separate languages, there is scope here for manipulation".[6]

A "Standard" Kashubian language does not exist despite attempts to create one, rather a variety of dialects are spoken that differ significantly from each other.[6] The vocabulary is influenced by both German and Polish.[6]

There are other traditional Slavic ethnic groups inhabiting Pomerania, including the Kociewiacy, Borowiacy and Krajniacy. These dialects tend to fall between Kashubian and the Polish dialects of Greater Poland and Mazovia. This might indicate that they are not only descendants of ancient Pomeranians, but also of settlers who arrived in Pomerania from Greater Poland and Masovia in the Middle Ages. However, this is only one possible explanation.

In the 16th and 17th century Michael Brüggemann (also known as Pontanus or Michał Mostnik), Simon Krofey (Szimon Krofej) and J.M. Sporgius introduced Kashubian into the Lutheran Church.[36] Krofey, pastor in Bütow (Bytow), published a religious song book in 1586, written in Polish but also containing some Kashubian words.[36] Brüggemann, pastor in Schmolsin, published a Polish translation of some works of Martin Luther (catechism) and biblical texts, also containing Kashubian elements.[36] Other biblical texts were published in 1700 by Sporgius, pastor in Schmolsin.[36] His "Schmolsiner Perikopen", most of which is written in the same Polish-Kashubian style as Krofey's and Brüggemann's books, also contain small passages ("6th Sunday after Epiphany") written in pure Kashubian.[36] Scientific interest in the Kashubian language was sparked by Christoph Mrongovius (publications in 1823, 1828), Florian Ceynowa and the Russian linguist Aleksander Hilferding (1859, 1862), later followed by Leon Biskupski (1883, 1891), Gotthelf Bronisch (1896, 1898), Jooseppi Julius Mikkola (1897), Kazimierz Nitsch (1903). Important works are S. Ramult's, Słownik jezyka pomorskiego, czyli kaszubskiego, 1893, and Friedrich Lorentz, Slovinzische Grammatik, 1903, Slovinzische Texte, 1905, and Slovinzisches Wörterbuch, 1908. Zdzisław Stieber was involved in producing linguistic atlases of Kashubian (1964–78).

The first activist of the Kashubian national movement was Florian Ceynowa. Among his accomplishments, he documented the Kashubian alphabet and grammar by 1879 and published a collection of ethnographic-historic stories of the life of the Kashubians (Skórb kaszébsko-slovjnckjé mòvé, 1866–1868). Another early writer in Kashubian was Hieronim Derdowski. The Young Kashubian movement followed, led by author Aleksander Majkowski, who wrote for the paper "Zrzësz Kaszëbskô" as part of the "Zrzëszincë" group. The group would contribute significantly to the development of the Kashubian literary language. Another important writer in Kashubian was Bernard Sychta (1907–1982).

Cultural traditions

Pussy willows appear to have been adopted as an alternative to the palm leaves used elsewhere in Easter celebrations, which were not obtainable in Kashubia. They were blessed by priests on Palm Sunday, following which parishioners whipped each other with the pussy willow branches, saying Wierzba bije, jô nie bijã. Za tidzéń wiôldżi dzéń, za nocë trzë i trzë są Jastrë ('The willow strikes, it's not me who strikes, in a week, on the great day, in three and three nights, there is the Easter').

The blessed by priests pussy willows were treated as sacred charms that could prevent lightning strikes, protect animals and encourage honey production. They were believed to bring health and good fortune to people as well, and it was traditional for one pussy willow bud to be swallowed on Palm Sunday to promote good health.

According to the old tradition, on Easter Monday Kashubian boys chase girls whipping gently their legs with juniper twigs. This is to bring good fortune in love to the chased girls. This was usually accompanied by a boy's chant Dyngus, dyngus - pò dwa jaja, Nie chcã chleba, leno jaja ('Dyngus, dyngus, for two eggs; I don't want bread but eggs'). Sometimes a girl would be whipped when still in her bed. Girls would give boys painted eggs.[37]

Pottery, one of the ancient Kashubians crafts, has survived to the present day. Famous is Kashubian embroidery.

The Pope’s John Paul II visit in June 1987, during which he appealed to the Kashubes to preserve their traditional values including their language, was very important[38].

Today

In 2005, Kashubian was for the first time made an official subject on the Polish matura exam (roughly equivalent to the English A-Level and French Baccalaureat). Despite an initial uptake of only 23 students, this development was seen as an important step in the official recognition and establishment of the language. Today, in some towns and villages in northern Poland, Kashubian is the second language spoken after Polish, and it is taught in regional schools.

Since 2005 Kashubian enjoys legal protection in Poland as an official regional language. It is the only tongue in Poland with this status. It was granted by an act of the Polish Parliament on January 6, 2005. Old Kashubian culture has partially survived in architecture and folk crafts such as pottery, plaiting, embroidery, amber-working, sculpturing and glasspainting.

In the 2011 census, 233,000 people in Poland declared their identity as Kashubian, 216,000 declaring it together with Polish and 16,000 as their only national-ethnic identity.[2] Kaszëbskô Jednota is an association of people who have the latter view.

Kashubian cuisine

Kashubian cuisine contains many elements from the wider European culinary tradition. Local specialities include:

- Czernina (Czarwina) – a type of soup made of goose blood

- Brzadowô zupa – a kind of sweet soup with e.g. apples

- Plińce

- Prażnica

Diaspora

Immigrant Kashubians kept a distinct identity among Polish Canadians and Polish Americans.

In 1858 Kashubians emigrated to Upper Canada and created the settlement of Wilno, in Renfrew County, Ontario, which still exists. Today Kashubs from Canada go to the homeland (Kashubia) to find out their own heritage. Kashubian immigrants founded St. Josaphat parish in Chicago's Lincoln Park community in the late 19th century, as well as the parish of Immaculate Heart of Mary in Irving Park, the vicinity of which was dubbed as "Little Cassubia". In the 1870s a fishing village was established in Jones Island in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, by Kashubian immigrants. The settlers however did not hold deeds to the land, and the government of Milwaukee evicted them as squatters in the 1940s, with the area soon after turned into industrial park. The last trace of this Milwaukee fishing village that had been settled by Kaszubs on Jones Island is in the name of the smallest park in the city, Kaszube's Park.[39]

See also Polish Canadians#Group-settlers, Paul Breza#Kashubian American activism.

Notable Kashubians

- Lech Bądkowski (1920–1984) writer, journalist, translator, political, cultural, and social activist

- Józef Borzyszkowski (1946- ) historian, politician, founder of the Kashubian Institute

- Paul Breza (1937- ) American priest, Kashubian-American activist

- Jan Romuald Byzewski (1842-1905) Kashubian-born American priest and social activist

- Florian Ceynowa (1817–1881) political activist, writer, linguist, and revolutionary

- Hieronim Derdowski (1852–1902) Kashubian-born American writer, newspaper editor, and political activist

- Konstantyn Dominik (1870-1942) auxiliary bishop of Chełmno (now Pelplin)

- Günter Grass (1927-2015 ) Nobel Prize-winning German author of Kashubian descent

- Yurek K. Hinz (1965- ) American computer scientist - professor

- Marian Jeliński (1949- ) Veterinarian, author, Kashubian activist

- Wojciech Kasperski (1981- ) film director, screenwriter

- Zenon Kitowski (1962- ) clarinet player

- Józef Kos (1900–2007) World War I veteran

- Gerard Labuda (1916–2010) historian

- Mark Lilla (1956-) American writer, intellectual historian

- Aleksander Majkowski (1876–1938) author, publicist, play writer, cultural activist

- Marian Majkowski (1926-2012) author, architect

- Paul Mattick (1904-1981) Marxist writer, social revolutionary

- Mestwin II (1220–1294) ruler of united Eastern Pomerania

- Paul Nipkow (1860–1940) inventor of the first television system called the nipkow disc

- Jerzy Samp (1951- ) writer, publicist, historian, and social activist

- Wawrzyniec Samp (1939- ) sculptor and graphic artist

- Franziska Schanzkowska (1896–1984); a.k.a. Anna Anderson, impostor who claimed to be, Anastasia Romanova, daughter of Tsar Nicholas II

- Danuta Stenka (1962- ) actress

- Swantopolk II (1195–1266) powerful ruler of Eastern Pomerania

- Brunon Synak is a professor of sociology and a Kashubian activist

- David Shulist (Kashubian: Dawid Szulëst) (1951- ) Mayor of Madawaska Valley, Ontario (Canada) and Kashubian activist

- Friedrich Bogislav von Tauentzien (1710-1791), Prussian general of the Seven Years' War

- Bogislav Friedrich Emanuel Graf Tauentzien von Wittenberg (1760-1824), Prussian general of the Napoleonic Wars and namesake of Tauentzienstraße in Berlin

- Jerzy Treder (1942- ), philologist and linguist, known as an expert in Kashubian studies

- Jan Trepczyk (1907-1989) poet, song-writer, lexicographer and creator of the Polish-Kashubian dictionary

- Donald Tusk (1957- ) historian, politician, leader of Civic Platform, Prime Minister of Poland and President of the EU

- Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg (1759-1830) Prussian Field Marshal of the Napoleonic era

- Erich von Manstein (Fritz Erich Georg Eduard von Lewinski) (1887–1973), German Field Marshal

- Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski (1899-1972)

- Emil von Zelewski (1854-1891), Prussian Officer

- Paul Yakabuski (1922-1987), First Kasubian MPP elected in Canada in 1963

- Jim Peplinski (1960- ), Captain of the NHL Flames and winner of the 1989 Stanley Cup

In literature

Important for Kashubian literature was Xążeczka dlo Kaszebov by Doctor Florian Ceynowa (1817–1881). Hieronim Derdowski (1852-1902) was another significant author who wrote in Kashubian, as was Doctor Aleksander Majkowski (1876–1938) from Kościerzyna, who wrote the Kashubian national epic The Life and Adventures of Remus. Jan Trepczyk was a poet who wrote in Kashubian, as was Stanisław Pestka. Kashubian literature has been translated into Czech, Polish, English, German, Belarusian, Slovene and Finnish. A considerable body of Christian literature has been translated into Kashubian, including the New Testament.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kashubians. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Kashubians |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Kashubes. |

References

- ↑ "The Institute for European Studies, Ethnological institute of UW" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-08-16.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Przynależność narodowo-etniczna ludności – wyniki spisu ludności i mieszkań 2011. GUS. Materiał na konferencję prasową w dniu 29. 01. 2013. p. 3. Retrieved on 2013-03-06.

- ↑ "Kashubes" in the Encyclopædia Britannica 11th ed., Vol. 15. 1911.

- ↑ Agata Grabowska, Pawel Ladykowski, The Change of the Cashubian Identity before Entering the EU, 2002

- ↑ Harry Hulst, Georg Bossong, Eurotyp, Walter de Gruyter, 1999, p. 837, ISBN 3-11-015750-0

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael, Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 199, ISBN 0-19-823671-9

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dicky Gilbers, John A. Nerbonne, J. Schaeken, Languages in Contact, Rodopi, 2000, p. 329, ISBN 90-420-1322-2

- ↑ Christina Yurkiw Bethin, Slavic Prosody: Language Change and Phonological Theory, pp. 160ff, Cambridge University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-521-59148-1.

- ↑ Edward Stankiewicz, The Accentual Patterns of the Slavic Languages, Stanford University Press, 1993, p. 291, ISBN 0-8047-2029-0

- ↑ Jan Mòrdawsczi: Geografia Kaszub/Geògrafia Kaszëb. dolmaczënk: Ida Czajinô, Róman Drzéżdżón, Marian Jelińsczi, Karól Rhode, Gdańsk Wydawn. Zrzeszenia Kaszubsko-Pomorskiego, Gduńsk 2008, p. 69

- ↑ A.Pielowski (28 November 2012), Historia Kartuz: Pochodzenie Kaszubów Kartuzy-Pradzieje.pl: Featured poem by Maryla Wolska: "Siedem miast od dawna / Kłóci się ze sobą, / Które to jest z nich / Wszech Kaszub głową: / Gdańsk – miasto liczne, / Kartuzy śliczne, / Święte Wejherowo, / Lębork, Bytowo, / Cna Kościerzyna / I Puck – perzyna."

- ↑ Kaszuby.info.pl, Przewodnik: "Kartuzy". Kaszubski Portal Internetowy.

- ↑ nowa.magazynswiat.pl/index

- ↑ Biuro RCS - Przemysław Rombel. "Kościerzyna kaszuby". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Bytów: Bytów stolicą Kaszub". 5 September 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Hartmut Boockmann, Ostpreussen und Westpreussen, Siedler 2002, p. 161,ISBN 3-88680-212-4

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Klaus Herbers, Nikolas Jaspert, Grenzräume und Grenzüberschreitungen im Vergleich: Der Osten und der Westen des mittelalterlichen Lateineuropa, 2007, pp. 76ff, ISBN 3-05-004155-2

- ↑ Werner Buchholz, Pommern, Siedler, 1999, pp.205-212, ISBN 3-88680-272-8

- ↑ Richard du Moulin Eckart, Geschichte der deutschen Universitäten, Georg Olms Verlag, 1976, pp.111,112, ISBN 3-487-06078-7

- ↑ Gerhard Krause, Horst Robert Balz, Gerhard Müller, Theologische Realenzyklopädie, Walter de Gruyter, 1997, pp.43ff, ISBN 3-11-015435-8

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Jerzy Jan Lerski, Piotr Wróbel, Richard J. Kozicki, Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1996, p. 62, ISBN 0-313-26007-9

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Historia Polski 1795-1918 Andrzej Chwalba, p. 439

- ↑ The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795-1918 (History of East Central Europe) Piotr S. Wandycz page 135

- ↑ Ireneus Lakowski, Das behinderten-bildungswesen im Preussischen Osten: Ost-west-gefälle, Germanisierung und das Wirken des Pädagogen, LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2001, pp.25ff, ISBN 382585261

- ↑ Gdańskie Zeszyty Humanistyczne: Seria pomorzoznawcza, p. 17, Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna (Gdańsk). Wydział Humanistyczny, Instytut Bałtycki, Instytut Bałtycki (Poland) - 1967

- ↑ Położenie mniejszości niemieckiej w Polsce 1918-1938, p. 183, Stanisław Potocki, 1969

- ↑ Rocznik gdański organ Towarzystwa Przyjaciół Nauki i Sztuki w Gdańsku - p. 100, 1983

- ↑ Do niepodległości 1918, 1944/45, 1989: wizje, drogi, spełnienie p. 43, Wojciech Wrzesiński - 1998

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 Jozef Borzyszkowski in Hans-Henning Hahn, Peter Kunze, Nationale Minderheiten und staatliche Minderheitenpolitik in Deutschland im 19. Jahrhundert, Akademie Verlag, 1999, p. 96, ISBN 3-05-003343-6

- ↑ Diemut Majer, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939-1945, Von Diemut Majer, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, JHU Press, 2003, p. 240, ISBN 0-8018-6493-3

- ↑ "Senat Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej / Nie znaleziono szukanej strony...". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Wiadomości - Aktualności - Musieliśmy się ukrywać : Nasze Kaszuby". Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ↑ "Erika z Rumii" Piotr Szubarczyk, IPN Bulletin 5(40) May 2004

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/LUD_ludnosc_stan_str_dem_spo_NSP2011.pdf

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 Peter Hauptmann, Günther Schulz, Kirche im Osten: Studien zur osteuropäischen Kirchengeschichte und Kirchenkunde, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2000, pp.44ff, ISBN 3-525-56393-0

- ↑ Malicki L.: Rok obrzędowy na Kaszubach, Wojewódzki Ośrodek Kultury, Gdańsk 1986, p. 35-39

- ↑ Gustavsson S: Polish, Kashubian and Sorbian, in: The Baltic Sea Region: Cultures, Politics, Societies, pp. 264-266,2002;Uppsala University Library

- ↑ A small patch of green where land and water meet

Further reading

- Synak, Brunon (December 1997). "The Kashubes during the post-communist transformation in Poland". Nationalities Papers 25 (4): 715–728. doi:10.1080/00905999708408536.

- Polish Cultural Institute (July 2001). "The Kashubian Polish Community of Southeastern Minnesota (MN) (Images of America)".

- Borzyszkowski J.: The Kashubs, Pomerania and Gdańsk; [transl. by Tomasz Wicherkiewicz] Gdańsk : Instytut Kaszubski : Uniwersytet Gdański ; Elbląg : Elbląska Uczelnia Humanistyczno-Ekonomiczna, 2005, ISBN 83-89079-35-6

- Obracht-Prondzyński C.: The Kashubs today : culture, language, identity; [transl. by Tomasz Wicherkiewicz] Gdańsk : Instytut Kaszubski, 2007, ISBN 978-83-89079-78-7

- Szulist W.: Kaszubi w Ameryce : Szkice i materiały, MPiMK-P Wejherowo 2005 (English summary).

- "The Kashubs Today" ISBN 978-83-89079-78-7

External links

- Kashubs 2002

- (Polish) http://www.zk-p.pl/

- (English) (Polish) http://kaszebsko.com/who-we-are-and-what-are-our-objectives.html

- (English) http://www.kashub.com/

- (English) (German) (Kashubian) (Polish) http://kaszubia.com/

- (Polish) (German) (English) http://www.republika.pl/modraglina/kaszlink.html

- http://www.cassubia-slavica.com/

- (English) (Kashubian) http://www.inyourpocket.com/poland/city/kashubia.html

- (English) Canada's Kashubian community celebrates heritage at Wilno

- (English) The Wilno Heritage Society

- (English) The Polish Cultural Institute and Museum of Winona, Minnesota

- (English) Cashubes

| ||||||||||||||||