Kanae Yamamoto (artist)

| Kanae Yamamoto | |

|---|---|

_Self-portrait.jpg) Self-portrait, oil painting, 1915 | |

| Native name |

山本 鼎 Yamamoto Kanae |

| Born |

October 24, 1882 Okazaki, Aichi, Japan |

| Died |

October 8, 1946 (aged 63) Ueda, Nagano, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Alma mater | Tokyo School of Fine Arts |

| Movement | Sōsaku-hanga |

| Spouse(s) | Ieko Yamamoto (née Kitahara) |

Kanae Yamamoto (山本 鼎, Japanese: [ka.na.e], 24 October 1882 – 8 October 1946) was a Japanese artist, known primarily for his prints and yōga Western-style paintings. He is credited with originating the sōsaku-hanga ("creative prints") movement, which aimed at self-expressive printmaking, in contrast to the commercial studio systems of ukiyo-e and shin-hanga. He initiated movements in folk arts and children's art education that continue to be influential in Japan.

Kanae trained as a wood engraver in the Western style before studying Western-style painting. While at art school he executed a two-colour print of a fisherman he had sketched on a trip to Chiba. Its publication ignited an interest in the expressive potential of prints that developed into the sōsaku-hanga movement. Kanae spent 1912 to 1916 in Europe. He brought back to Japan ideas gleaned from exhibitions of peasant crafts and children's art in Russia and in the late 1910s founded movements the promotion of creative peasant crafts and in children's art education; the latter quickly gained adherents but was suppressed under Japan's growing militarism and had to wait until after World War II for a revival.

Though always a supporter, Kanae left behind printmaking in the 1920s and devoted his artistic output to painting until he suffered a stroke in 1942. He spent his remaining years in mountainous Nagano in the city of Ueda, where the Kanae Yamamoto Memorial Museum was erected in 1962.

Life and career

Early life and training (1882–1907)

Kanae Yamamoto descended from the Irie clan of hatamoto—samurai in the direct service of the Tokugawa shogunate of feudal Japan in Edo (modern Tokyo). His grandfather died 1868 in the Battle of Ueno, during the Boshin War which led to the fall of the Shogunate and the Meiji Restoration which returned power to the Emperor.[1] This orphaned Kanae's father Ichirō,[lower-alpha 1] and thereafter he grew up in Okazaki in Aichi Prefecture; how he got there is a matter of speculation.[2] Ryōsai Yamamoto[lower-alpha 2] took in Ichirō with the intention of raising him to marry the family's eldest daughter[3] Take.[lower-alpha 3][4]

Kanae was born 24 October 1882 in the Tenma-dōri 1-chōme neighbourhood of Okazaki.[lower-alpha 4] Ryōsai intended Ichirō to continue the Yamamoto line of specialists in traditional Chinese medicine, but when the Meiji government announced it grant medical licenses only to those who practised Western medicine, Ichirō moved to Tokyo to study it shortly after Kanae's birth. He lodged in the household of Mori Ōgai's father, where he performed household duties to earn his keep. To advance his studies he took part the clandestine digging up of fresh graves to find bodies to dissect.[3]

When he was five Kanae and his mother joined Ichirō in Tokyo and settled in a tenement house in the San'ya area.[3] His mother did sewing work to help support the family,[4] and with her sister Tama[lower-alpha 5] provided maid service to the Mori household, and thus Kanae often met his younger cousin, Kaita Murayama, who like Kanae was to make a career in art.[5] The painter Harada Naojirō , whom Ōgai had befirended when the two were studying in Germany,[lower-alpha 6] asked Kanae's mother, whom he had seen at the Mori household, to model for the painting Kannon Bodhisattva Riding the Dragon of 1890. Such aoocurances may have contributed to drawing Kanae to art.[6]

.jpg)

Harada Naojirō , oil on canvas, 1890.

Ichirō raised his son under the influence of the liberal educational principles of Nakae Chōmin.[7] At age 11,[8] after four years of primary school,[4] the family finances did not permit Kanae's schooling to continue.[7] He became an apprentice wood engraver and mastered Western techniques of tonal gradation[4] in the workshop of Sakurai Torakichi in Shiba.[8] His training focused on book and newspaper illustration, and included letterpress printing and photoengraving.[7] His skill developed quickly and soon won praise from those he worked with.[9] During this time printing technology underwent rapid change, brought to the forefront by the First Sino-Japanese War,[lower-alpha 7] which was reported in a variety of media, from paintings and woodblock prints to photographs.[10] Kanae completed his apprenticeship at 18, followed by an obligatory year of service with Sakurai.[10] By this time Ichirō had earned his medical license and set up a practice in Kangawa (now part of Ueda), a village in Nagano Prefecture.[11]

The rapid change in printing technology led Kanae to doubt his future prospects in wood engraving.[12] He aspired to become a painter[13] but knew his yet-indebted father was not in a position to pay for art school. He secretly enrolled at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1902,[11] where he studied yōga Western-style painting.[4] His instructors there included Masaki Naohiko , Tōru Iwamura , and Kuroda Seiki.[14]

To pay for school Kanae worked odd printing jobs for employers such as the Hochi Shimbun newspaper,[11] and from February 1903 lodged at the home of his friend Hakutei Ishii ,[14] the eldest son of the artist Ishii Teiko .[8] Kanae and the other aspiring artists lodged there talked into the night about art and hired a model for life drawing once a month.[14]

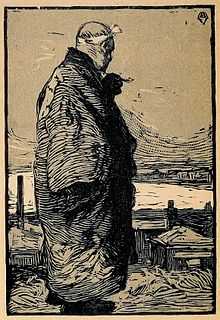

Prints and sōsaku hanga (1904–1912)

While at the School of Fine Arts, Kanae made a hiking trip in 1904 to Chōshi in Chiba Prefecture where he made a sketch of a fisherman dressed in ceremonial clothing overlooking a harbour. When he returned, he used the sketch as the basis of a wood engraving.[15] He engraved on both sides of a single piece of wood: the one side he printed in ochre, which filled in all the spaces except the towel on the fisherman's head; the other he printed in black, which provided outlines and details.[8] At the time, the art establishment saw woodblock printing as a commercial venture beneath the station of an aspiring fine artist.[16]

Hakutei noticed the print and had it published in the literary magazine Myōjō that July.[8] In a column in the issue Ishii promoted the print as revolutionary, as it had been done as a means of painterly spontaneous self-expression, and used methods Ishii associated with ukiyo-e traditions.[17] Soon the style Ishii dubbed tōga[lower-alpha 8] became a popular topic within Myōjō circles. This was to grow into the sōsaku-hanga ("creative prints") movement.[18]

In 1905 Kanae, Ishii Hakutei, Ishii Tsuzurō, and some other friends founded the short-lived magazine Heitan in which they published a number of their prints. It was in Heitan that the word hanga[lower-alpha 9] first appeared. The word was used interchangeably with tōga until the magazine came to an end in April 1906; thereafter tōga fell out of use and hanga went on to become the modern Japanese word for prints in general.[19]

After graduating in September 1906 from the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, Kanae took work at Rakuten Kitazawa's cartoon humour magazine Tokyo Puck, patterned after the American Puck. In May 1907,[20] Kanae, Hakutei, and a former art-school classmate of Kanae's, Morita Tsunetomo, founded the monthly magazine Hōsun.[lower-alpha 10][19] The contents were primarily literature, criticism, and art cartoons,[20] and its publishers paid fine attention to details of graphic design. They printed the magazine on fine paper at an unusually large size[lower-alpha 11] and mixed colour reproduction with black-and-white. Kanae's contributions included his own prints, haiku poetry, and the carving of printing blocks for the designs of others.[19] Kanae's former engraving teacher Sakurai Torakichi furnished the photographic printing plates.[21] The first issue was eight pages and included a supplementary print of Shiba Park by Kanae. The young artists distributed the issue themselves to bookstores. It sold well, and the circle of contributors grew, as did the page count, which expanded to sixteen.[22]

Tokyo during the Meiji period (1868–1912) had a great openness to foreign—especially European—influence, and Western trends in art were quickly replacing traditional Japanese ones until word was heard of the impact exported ukiyo-e had had on art in the West. Artists who had all but abandoned the culture of the Edo period began to reconsider it and mix elements of it with Western approaches.[23] Kanae took part in meetings of the Pan no Kai groups of writers and artists whose goal was to replicate the atmosphere of Parisian cafés such as Café Guerbois of the Impressionists. At one of these rowdy bohemian meetings, a drunken Kanae fell through a window and landed in the garden below, wrapped in a shōji paper screen; he returned to the gathering as if nothing had happened. The police kept watch over these meetings whose members they suspected of having socialist sympathies and held grudges over caricatures some of the members had published. Pan no Kai lasted until 1911;[24] that July Hōsun came to an end after thirty-five issues.[19]

_S%C5%8Dga_butai_sugata_-_Ch%C5%8Dj%C5%ABr%C5%8D_no_Atsumori.jpg)

Kanae wanted to revive the spirit of Edo-period ukiyo-e in his prints, and to this end in 1911 he founded the Tokyo Print Club to produce and distribute such prints. He advertised for members in Hōsun, but after the magazine's demise most of the associated artists left Tokyo and the only member he could recruit was Hanjirō Sakamoto. The pair began a series titled Sōga-butai sugata ("Stage Figure Sketches") of portraits of kabuki actors in the vein of the yakusha-e genre of ukiyo-e. The subjects were sketched from performances at the just-built Imperial Theatre and were captioned in French on the front and on the back in Japanese. Though Kanae had announced that prints were to come from thirty-four theatre pieces only three sets of four prints—two by each artist in each set—appeared in June, July, and September that year.[25] The work represents a major turning point in his career as he turned away from the Western techniques that had defined his work toward a more Japanese approach such as the use flat areas of colour.[26]

Europe (1912–1916)

Kanae had wanted to marry Ishii Mitsu, but her family forbade it—especially her mother and brother Hakutei. This rejection embittered him and he broke his friendship with Hakutei, though he remained friends with Tsuruzō.[27] Kanae wished to study painting in Paris, so his father organized the distribution and sale of his son's work to raise funds for it while he was away.[28] He set off on the Tango Maru from Kobe on on 6 July 1912,[4] and fifty-three days later landed in Marseilles. While on board he made what was likely the first of the prints he father was to sell for him by subscription: titled Wild Chickens, it depicted three Chinese prostitutes with bound feet inspired by prostitutes he saw when he passed through Shanghai. He printed it in Paris, where in his first few months he studied etching at the École des Beaux-Arts.[28]

Upon arrival Kanae contacted the painter Sanzo Wada, who had been in Paris since 1907. Wada introduced him to Kunishirō Mitsutani, and Kanae soon moved into a studio next to Mitsutani's. He found French difficult to master and associated mostly with expatriate Japanese artists such as Ryuzaburo Umehara and Sōtarō Yasui.[29] His closest friend there was Misei Kosugi, a contributor to Hōsun who arrived in March 1913 to spend a year travelling Europe.[30]

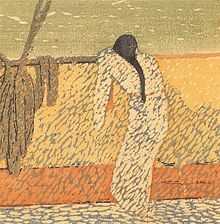

In 1913 the writer Tōson Shimazaki visited Kanae, whom he had known from Ueda. The two shared the recent experience of having been denied a marriage. Tōson wrote of the print On the Deck that Kanae was finding difficult to finish: a print of a long-haired woman on the deck of the Tango Maru as it was in Singapore. It was made with six cherry woodblocks on mulberry washi paper, materials Kanae had brought from Japan. The print was sent to Japan that May.[31] The pair went to seaside Brittany for six weeks from that July, and soon were joined by a number of other artists, all of whom were drawn there by the tales of the beauty of the region Kuroda Seiki had written in the 19th century.[31] Kanae was particularly productive of prints while in Brittany.[32]

Kanae felt isolated from the culture and found little art there that he appreciated. He disliked the paintings of van Gogh, Monet, and Édouard Manet.[30] He liked the works of Renoir and Sisley, and Puvis de Chavannes,[30] admired the paintings of Cézanne, but denied any connection between them and those of the Cubists whose works he denigrated;[33] he wrote that only one in three thousand paintings of Matisse were good.[33]

_Cow.jpg)

Kanae imagined himself a realist[33] and was distressed at the avant-garde that was coming to dominate the European art world;[34] he found it difficult to comprehend and reconcile it with his understanding of a realist ideal in Western art.[32] His disappointment and confusion impacted his productivity; he produced few of the prints that were supposed to fund his stay, and the language barrier made it difficult to find buyers.[35] A Tokyo agent of his committed suicide after appropriating money from Kanae and other clients. He could not bring himself to reveal his and his parents' financial situation, so he had another agent, Rokurō Watanabe, send money to Paris just so he could send it back to his parents, who were under pressure from a loan shark.[35] Along with his disappointment in the Western art world, Kanae witnessed first-hand the impact Japanese art had had there. Though he kept such thoughts to himself he began to feel a sense of the superiority of Japanese art—of the same traditions he had denied himself during his years of training.[36]

Kanae managed to acquire funds from connections and refused to return early to Japan despite the urgings of friends and associates. Troubles thickened in mid-1914 when World War I broke out and he learned that Mitsu Ishii had married. The war drove him from Paris to London where he stayed for four months, much of it sick with bronchitis.[34] He returned to Paris on 11 January 1915,[37] but work was scarce and the museums were closed. He resolved to return to Japan the following spring, but first moved with a group of Japanese compatriots to Lyon where he found work that brought in enough money for a trip to Italy in March 1916 to see the Renaissance masterpieces. Upon returning to Lyon he learned of the death of Sakurai and finally prepared to go back to Japan.[38]

The least expensive route for Kanae to Japan was through Russia. He set off from Paris on 30 June 1916 via England, Norway, and Sweden. In Moscow he met the Japanese consul and the social critic Noburu Katagami; the latter introduced him to proletarian art[38] and encouraged him to visit Yasnaya Polyana, Leo Tolstoy's home which he had made into a farmers' school. The experienced moved Kanae, who later was to write, "While I was staying in Moscow in the summer of 1916, I felt that I had two important missions. One was promotion of children's free painting and the other was establishment of farmers' art."[38] Kanae visited the Moscow Kustar' Museum, which had exhibited peasant arts and crafts since 1885. He praised its sturdy quality and ethnic design, and lamented that industrialization had brought about a degradation in its perceived value and was threatening its survival.[39] An exhibition of children's art impressed Kanae with its free expressiveness.[40]

Towards the end of 1916 Kanae made the long rail trip across Siberia. Along the way he received a telegram from the poet Hakushū Kitahara. The two had been negotiating the hand of Kitahara's sister Ieko and had finally reached an agreement.[41]

Return to Japan and later career (1916–1935)

Kanae returned to Japan in December 1916 and took over Sakurai's struggling printing company, which he renamed Seiwadō. In autumn 1917 he had seventeen yōga oil paintings displayed at the Nihon Bijutsuin's Inten exhibition. The same year he married Ieko Kitahara, had an instruction book on oil painting published, and finished a number of prints whose subscriptions had been paid for.[41]

Kanae aimed at putting together a creative prints association.[42] In June 1918 Kanae co-founded the Nihon Sōsaku-Hanga Kyōkai ("Japan Creative Print Cooperative Society") with lithographer Kazuma Oda, etcher Takeo Terasaki, and woodblock artist Kogan Tobari; this last had been a member of the Pan no Kai and had also recently returned from several years in Europe. The group held its first exhibition at the art gallery in the Mitsukoshi building in Nihonbashi on 15–20 January 1919.[43] It represented 277 works by 26 artists, including seventeen woodblock prints and two etchings by Kanae. The show drew twenty thousand visitors and was widely reported in the media, including a special sōsaku-hanga issue that March of the prominent art magazine Mizu-e which included an article in which Kanae outlined the principles of the artform and the goals of the Nihon Sōsaku-Hanga Kyōkai. That May the show was repeated at the Mitsukoshi location in Osaka.[44]

In 1919 Kanae founded the Japan Children's Free Drawing Association[lower-alpha 12] and held its first exhibition. The public was impressed by its democratic ideals, as the idea of democratic education was gaining momentum in Japan during the Taishō period (1912–26). Kanae propounded the importance of teaching students freedom, without which they cannot grow, and denigrated the tradition of teaching drawing through copying. He promoted this ideas in 1921 with the book Free Drawing Education[40] and the monthly magazine Education of Arts and Freedom.[lower-alpha 13][45] Kanae's methods were widely adopted, and it became common for teachers to take students outdoors to draw from nature.[40] These ideas did not escape criticism, and the rise of militarism in Japan put an end to Kanae's movement in 1928; it was not to be revived until after World War II.[45]

Later in 1919 Kanae moved to Ueda, the mountainous Nagano village where his parents lived. He secured funding from the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Agriculture, and Mitsubishi to set up a school[46][lower-alpha 14] that December[47] to teach to the rural population arts and crafts skills they could use to augment their incomes during the long winter months[46] as part of a peasant art movement that combined creativity and utility,[39][lower-alpha 15] inspired by the peasant crafts he had seen in Russia.[39]

In 1921, brothers-in-law Rinzō Satake and Shōkō Sasaki consulted with Kanae to develop a pastel crayon with an oil binder; development took three years and resulted in the world's first oil pastel, marketed under the name Cray-Pas through the Sakura Color Products Corporation.[48]

The peasant hart movement had success in intellectual and government circles. A show at Mitsukoshi of works by sixteen youths was well received. In 1923 Kanae established the Japan Peasant Art Institute[lower-alpha 16] which expanded throughout the country with the help of increased government funding in 1925.[39] Critics of the movement saw it as an anachronism or of stripping rural handicrafts of their original charm through commercialism;[39] Kanae saw movement as motivated by a desire to keep creative vitality alive, and not by a sense of nostalgia or desire to preserve older ways.[39]

The police suspected Kanae of socialist sympathies as he had brought the idea from Russia.[46] The police so harassed him that he asked Un'ichi Hiratsuka, who was teaching frame-making there, to give up wearing his Russian-style jacket and to cut his long hair.[49] Kanae's initial enthusiasm dwindled over the next five years—funding shrank, finding other patrons was wearying, the village mayor went bankrupt,[46] and his attempts to find ways for the farmers to make money off their artwork found little success.[50] After five years the venture went bankrupt.[49]

Kanae turned his focus from printmaking to painting. He was a founding member in 1922 of the Shunyōkai association for painters who wished to maintain connections with Japanese traditions in the face of the Westernization of academic painting in Japan. He was editor of the association's members' magazine Atorie.[lower-alpha 17] He continued to promote the work of print artists and the legitimacy of prints as art. In 1928 the magazine devoted an issue to sōsaku hanga, and from the same year Shunyōkai included a prize in the print category in its annual exhibitions.[51]

In 1924 Kanae travelled to Taiwan for a month to observe local folk craft and advise the government on how to develop the industry. The utilitarian craftwork of the aboriginal Taiwanese people impressed him beyond his expectations.[52] Taiwanese authorities thought to promote the production of bamboo and rattan craftwork, but Kanae thought they could not compete with similar products from Japan and promoted instead the production of products both traditional and new with a distinctive local flavour using traditional designs for sale as souvenirs and exports.[53]

After the 1919 show, Kanae passed the leadership of the Nihon Sōsaku-Hanga Kyōkai[lower-alpha 18] to Kōshirō Onchi.[54] In 1931 it became the more comprehensive Nihon Hanga Kyōkai ("Japan Print Cooperative Society").[43] The same year the Seiwadō printing company went out of business.[41]

Return to painting and final years (1935–1946)

_Haruna-ko_shosh%C5%AB.jpg)

In 1935 Kanae settled in Tokyo and returned to painting full-time. He produced a number of oils and watercolours that were exhibited in January 1940 at the Mitsukoshi gallery. The show was well received and attended, and in a dinner that followed Kanae proclaimed, "I shall live until May of my eighty-fifth year. Therefore, I am going to sit back now, and drink sake, and paint to my heart's content."[50]

While at by Lake Haruna in Gunma Prefecture[55] in 1942 Kanae suffered a cerebral hemorrhage[50] which partially paralyzed him and hindered his ability to paint. He continued to paint as much as he could for the rest of his life, hindered by war shortages, and turned to watercolour when oil painting was too demanding under his disability. In spring 1943[55] he moved to Ueda in Nagano where he spent his remaining years. He died on 8 October 1946[56] undergoing surgery for a volvulus at the Nisshindō hospital in Ueda.[47]

Style

In his prints, Kanae's primary tool was a curved-blade chisel; in ukiyo-e this tool was normally for clean up and a straight chisel for the main carving. His carving followed the Western approach of carving out planes and lines to appear in white, whereas the traditional Japanese technique was to carve around the lines to be printed.[57]

- Prints by Kanae Yamamoto

-

_Chinese_Woman.jpg)

Chinese Woman, 1917

-

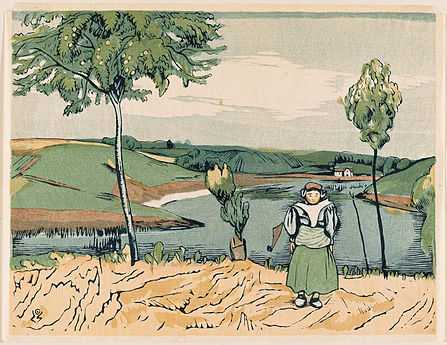

Dutch Girl in Landscape, 1915

-

_Burutonnu.jpg)

Breton Woman, 1920

-

Fishermen

- Paintings by Kanae Yamamoto

-

_Kach%C5%8D.jpg)

Mosquito Net, 1905

-

_Burut%C4%81nyu_no_natsu.jpg)

Summer in Breton, 1913

-

_Takahashi_Hama_sh%C5%8Dz%C5%8D.jpg)

Portrait of Hama Takahashi, 1917

-

_Tokko_Sanroku_Sh%C5%ABi.jpg)

Signs of Autumn at the Foot of Mount Tokko, 1926

-

_Kami-Ide_no_Fuji.jpg)

Mount Fuji from Kami-Ide, 1938

-

_K%C5%8Dgen_-_Iizuna.jpg)

Iizuna Highlands, 1939

Legacy

When an idea excited him he would bury himself in it. Sacrifice meant nothing. It was the same with creative hanga, his school, and his free-art movement. He was a selfless man, a passionate man, a man of great sensitivity. I guess if I had to describe him in one word it would be—artist.

Kanae's European work had an immediate effect on artists of his generation. In them Kōshirō Onchi saw the potential of of the woodcut medium, though his style owes more to European artists.[59] Un'ichi Hiratsuka came to believe "a real artist ... must cut his own blocks and do his own printing" as "Dürer and Bewick worked".[60] Sōsaku-hanga artists followed Kanae's lead in using a curved chisel to carve out planes rather than to define lines as in Japanese tradition.[57]

The dating of most of Kanae's work is uncertain. It is believed that the works he signed in Roman characters were made after he returned to Japan from Europe.[61] The number of copies of Kanae's prints is unknown; it is supposed the subscription prints he made in Europe numbered around 25 to 50.[61] Kanae made few printings of the Fisherman print—perhaps only one or two—and none have survived. The Ishiis discovered the block in their house decades later, and Oliver Statler had Hashimoto Okiie make forty copies of a commemorative edition in 1960.[18]

Modern Japanese thought on art education begins with Kanae's Free Drawing Education approach.[62] His stature in the history of child art and art education is similar to that of Franz Cižek's in the West.[63] Elementary schools teachers took to his ideas quickly in the wake of their dissatisfaction with the New Textbooks of Drawing [lower-alpha 19] textbooks the government had mandated in 1910 that emphasized copying and neglected personal expression. Yamamoto's was the first public criticism of the textbooks, and his methods led to a sharp decline in their use in the 1920s.[62] Yamamoto encouraged teachers to take children outdoors to sketch, a practice that continues to be common in Japanese elementary schools.[63] Though Japanese militarism put his ideas on hold from the late 1920s[45] educators revived and expanded them beginning in the 1950s.[63]

The municipal Kanae Yamamoto Memorial Museum[lower-alpha 20] in Ueda in Nagano Prefecture dates from 1962. It houses 1,800 items, including artwork and documents by Kanae and early examples of peasant crafts and children's artwork done under his instruction.[64]

Notes

- ↑ Yamamoto Ichirō, 山本 一郎

- ↑ Yamamoto Ryōsai, 山本 良斎

- ↑ Yamamoto Take, 山本 タケ

- ↑ The bombing of Okazaki in World War II obliterated the neighbourhood and much of central Okazaki, and no trace remains of the house of Kanae's birth.[1]

- ↑ Template:Tranls, 山本 タマ, third daughter of Ryōsai

- ↑ Ōgai studied medicine via the Imperial Japanese Army from 1884 to 1888; Harada studied art there from 1884 to 1887.

- ↑ At the height of the war, the teenage Kanae gave serious consideration to a future career in the military.[9]

- ↑ tōga (刀画, "blade picture")

- ↑ Hanga (版画 printed picture)

- ↑ hōsun (方寸, "one's mind; the space occupied by one's heart")

- ↑ The pages of Hōsun were 31.3 × 23.2 centimetres (12.3 × 9.1 in)

- ↑ Japan Children's Free Drawing Association (日本児童自由画協会 Nihon jidō jiyūga kyōkai)

- ↑ Education of Arts and Freedom (芸術自由教育 Geijutsu jiyū kyōiku)[45]

- ↑ Kanae set up the school in part of Kangawa Elementary School in the village of Kangawa (now part of Ueda).[47]

- ↑ Peasant art movement (農民美術運動 nōmin bijutsu undō)[39]

- ↑ Japan Peasant Art Institute (農民美術練習所 Nōmin bijutsu renshūjo)

- ↑ Atorie is the Japanese pronunciation of the French word atelier "workshop".

- ↑ Nihon Sōsaku-Hanga Kyōkai, (日本版画協会 , "Japan Creative Prints Society")

- ↑ Shintei gachō (新定画帖)

- ↑ Kanae Yamamoto Memorial Museum (山本鼎記念美術館 Yamamoto Kanae Kinen Bijutsukan)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Kosaki 1979, p. 12.

- ↑ Kosaki 1979, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Kosaki 1979, p. 13.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Merritt 1990, p. 156.

- ↑ Kuboshima 2007, p. 50.

- ↑ Kosaki 1979, p. 14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Nakazawa 1976, p. 38.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Merritt 1990, p. 111.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kosaki 1979, p. 15.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kosaki 1979, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Kosaki 1979, p. 17.

- ↑ Kosaki 1979, p. 16.

- ↑ Statler 1959, p. 10.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Kosaki 1979, p. 18.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 109.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 110.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Merritt 1990, p. 112.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Merritt 1990, p. 113.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Nakazawa 1976, p. 42.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 116.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 114.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 120.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 123.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Merritt 1990, p. 157.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Merritt 1990, p. 159.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Merritt 1990, p. 158.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Merritt 1990, p. 161.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Merritt 1990, p. 160.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Merritt 1990, p. 164.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Merritt 1990, p. 162.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Merritt 1990, p. 165.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 Long 2012, p. 162.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Kaneda 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Long 2012, p. 166.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Merritt 1990, p. 138.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Kaneda 2003, p. 4.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Statler 1959, p. 15.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Municipal Museum Kanae Yamamoto staff.

- ↑ Baggetta, Schneider & Rohlander 2010, p. 90.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Statler 1959, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Statler 1959, p. 16.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 143.

- ↑ Kikuchi 2007, p. 219.

- ↑ Kikuchi 2007, pp. 219–220.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Merritt 1990, p. 176.

- ↑ Statler 1959, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Statler 1959, p. 13.

- ↑ Statler 1959, p. 17.

- ↑ Michener 1983, p. 249.

- ↑ Michener 1983, pp. 252–253.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Statler 1959, p. 185.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Romans 2005, p. 232.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Romans 2005, p. 235.

- ↑ Suzuki 1985, pp. 105–107.

Works cited

- Baggetta, Marla; Schneider, William; Rohlander, Nathan (2010). The Art of Pastel: Discover Techniques for Creating Beautiful Works of Art in Pastel. Walter Foster. ISBN 978-1-60058-195-3.

- Kaneda, Takuya (Winter 2003). "The Concept of Freedom in Art Education in Japan". Journal of Aesthetic Education (University of Illinois Press) 37 (4): 12–19. JSTOR 3527329.

- Kikuchi, Yūko (2007). Refracted Modernity: Visual Culture and Identity in Colonial Taiwan. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3050-2.

- Kosaki, Gunji (1979). Yamamoto Kanae hyōden: Yume ōki senkaku no gaka 山本鼎評伝: 夢多き先覚の画家 [Kanae Yamamoto critical biography: Pioneer artist of many dreams]. Shinanoji. OCLC 33580621.

- Long, Hoyt (2012). On Uneven Ground: Miyazawa Kenji and the Making of Place in Modern Japan. Stanford University Press. (subscription required (help)).

- Merritt, Helen (1990). Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. University of Hawaii Press. (subscription required (help)).

- Michener, James Albert (1983). The Floating World. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0873-0.

- Municipal Museum Kanae Yamamoto staff. "Nōmin bijutsu hachijū shūnen yakushi nenpyō" 農民美術80周年略史年表 [80th anniversary of farmers' art: Brief chronology]. Municipal Museum Kanae Yamamoto website (in Japanese). Ueda City Multimedia Information Center. Archived from the original on 2006-07-17. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- Nakazawa, Kanao (1976-03-31). "Yamamoto Kanae no geijutsu shisō to jiyūga kyōiku-ron" 山本鼎の芸術思想と自由画教育論 [Idea on fine art of Kanae Yamamoto and his educational theory of the "Jiyuga (Children's free drawing)"] (PDF). Jinbun Gakuhō (11): 37–89.

- Romans, Mervyn (2005). Histories of Art and Design Education: Collected Essays. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-84150-131-4.

- Statler, Oliver (1959). Modern Japanese Prints: An Art Reborn. Charles E. Tuttle Company. ISBN 978-1-4629-0955-1.

- Suzuki, Kiyoshi (1985). Shinshū no bijutsukan 信州の美術館 [Art Museums of Shinshū] (in Japanese). Hoikusha. ISBN 978-4-586-50680-4.

- Kuboshima, Seiichirō (2007). Kanae Kaita e no tabi 鼎、槐多への旅 [Trip to Kanae, Kaita] (in Japanese). Shinano Mainichi Shimbunsha. ISBN 978-4-7840-7055-8.

Further reading

- Kanda, Aiko (2009). Yamamoto Kanae monogatari: Jidō jiyūga to nōmin bijutsu Shinshū Ueda kara yume wo otta otoko 山本鼎物語: 児童自由画と農民美術信州上田から夢を追った男 [The tale of Yamamoto Kanae: Children's free drawing and farmers' art, the man who followed his dream from Ueda, Nagano] (in Japanese). Shinano Mainichi Shimbunsha. ISBN 978-4-7840-7106-7.

- Kuboshima, Seiichirō (1999). Kanae to Kaita: Waga-seimei no homura Shinano no sora ni todoke 鼎と槐多: わが生命の焔(ほむら)信濃の天(そら)にとどけ [Kanae and Kaita: The flame of life–to the skies of Shinano] (in Japanese). Shinano Mainichi Shimbunsha. ISBN 978-4-7840-9852-1.

- Miyazaka, Katsuhiko (1988). Yamamoto Kanae: Taito naki yume mote 山本鼎: 退路なき夢もて [Kanae Yamamoto: No retreat from the dream] (in Japanese). Ginga Shobō.

External links

-

Media related to Yamamoto Kanae (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yamamoto Kanae (category) at Wikimedia Commons - Municipal Museum Kanae Yamamoto in Ueda, Nagano

|