KV2

| KV2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Burial site of Ramesses IV | |||

| |||

KV2 | |||

| Coordinates | 25°44′29.2″N 32°36′07.7″E / 25.741444°N 32.602139°ECoordinates: 25°44′29.2″N 32°36′07.7″E / 25.741444°N 32.602139°E | ||

| Location | East Valley of the Kings | ||

| Discovered | Open since antiquity | ||

| Excavated by | Edward R. Ayrton | ||

| Decoration |

| ||

|

| |||

Tomb KV2, found in the Valley of the Kings, is the tomb of Ramesses IV, and is located low down in the main valley, between KV7 and KV1. It has been open since antiquity and contains a large amount of graffiti.

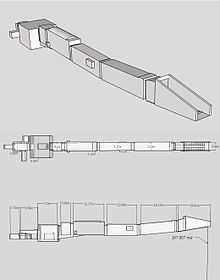

Contemporary plans of the tomb

There are two known plans of the tomb's layout contemporary to its construction. One on papyrus (now located at the Egyptian Museum in Turin) provides a detailed depiction of the tomb at 1:28 scale. All of the passages and chambers are present, with measurements written in hieratic script. The papyrus plan also depicts the pharaoh's sarcophagus surrounded by four concentric sets of shrines, the same layout of shrines that were found intact within Tutankhamun's tomb.[1] The other plan of the tomb was found inscribed on a slab of limestone not far from the tomb's entrance, and is a rough layout of the tomb depicting the location of its doors. The latter plan may have just been a "workman's doodle"[2] but the papyrus plan almost certainly had a deeper ritual meaning, and may have been used to consecrate the tomb after it was built.[1]

Tomb layout

A hieratic ostracon has been discovered mentioning the founding of the tomb, its place selected by the local Governor and two of the pharaoh's chief attendants in the second year of his reign.[3] Ramesses IV ascended the throne late in life, and to ensure that he would have a sizable tomb (during what would be a relatively brief reign of about six years), he doubled the size of the existing work gangs at Deir el-Medina to a total of 120 men.[4] Though sizable, KV2 has been described as being "simplistic" in its design and decoration.[5] The tomb was excavated at the base of a hill on the northwest side of the Valley of the Kings.

Like other tombs of the 20th Dynasty, KV2 is laid out along a straight axis. The successors of Ramesses III from this dynasty constructed tombs that follow this pattern and most were decorated in a similar manner to each other.

The tomb has a maximum length of 88.66 m[6] and consists of three slowly descending corridors labeled B, C, and D. This is followed by an enlarged chamber (E), and then the burial chamber (J). Past the burial chamber lies a narrow corridor (K) flanked by three side chambers [Ka, Kb and Kc].[7]

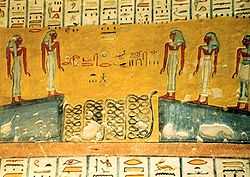

The tomb is mostly intact and is decorated with scenes from the Litany of Ra, Book of Caverns, Book of the Dead, Book of Amduat and the Book of the Heavens.

The sarcophagus is broken (probably in antiquity), and the mummy was relocated to the mummy cache in KV35.[8]

Visits in antiquity

The tomb was one of about eleven tombs open to early travelers. KV2 contains the second-highest number of ancient graffiti within it (after KV9), with 656 individual griffitos left by both Ancient Greek and Roman visitors.[9] This tomb also contains around 50 or so examples of Coptic graffiti, mostly sketched onto the right wall by the entranceway,[10] The tomb was likely used as a dwelling by Coptic monks,[11] and there are also depictions of Coptic saints and crosses on the tomb's walls.[7]

Early European visitors to the area included Richard Pococke, who visited KV2 and designated it "Tomb B" in his Observations of Egypt, published in 1743.[12]

The savants accompanying Napoleon's campaign in Egypt surveyed the Valley of the Kings and designated KV2 as "IIe Tombeau" ("2nd Tomb") in their list.[12] Other visitors of note included James Burton who mapped out the tomb in 1825, and the Franco-Tuscan Expedition of 1828-1829 did an epigraphic survey of the tomb's inscriptions.[7]

Modern archeological work

Archeologist Edward Ayrton excavated the entranceway to the tomb during 1905/1906, followed by Howard Carter in 1920. Both of them found remnants of the materials which had originally come from inside the tomb, such as shabtis, numerous ostraca and fragments of wood, glass and Faience.[11]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dodson, Aidan and Ikram, Salima. The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. p. 27. Thames & Hudson. 2008. ISBN 0-500-05139-9

- ↑ Dodson, Aidan and Ikram, Salima. The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. p. 162. Thames & Hudson. 2008. ISBN 0-500-05139-9

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas. Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Valley of the Kings. Thames & Hudson. p. 162. 1997. (Reprint) ISBN 0-500-05080-5

- ↑ Dodson, Aidan and Ikram, Salima. The Tomb in Ancient Egypt. p. 32. Thames & Hudson. 2008. ISBN 0-500-05139-9

- ↑ The Tomb of Ramesses IV, Valley of the Kings, Egypt, accessed July 15, 2009

- ↑ KV 2 (Rameses IV) - Theban Mapping Project, accessed July 14, 2009

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 KV 2 (Rameses IV) - Theban Mapping Project, accessed July 15, 2009

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas. Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Valley of the Kings. p. 163. Thames & Hudson. 1997. (Reprint) ISBN 0-500-05080-5

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas. Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Valley of the Kings. p. 51. Thames & Hudson. 1997. (Reprint) ISBN 0-500-05080-5

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas. Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Valley of the Kings. p. 50. Thames & Hudson. 1997. (Reprint) ISBN 0-500-05080-5

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Reeves, Nicholas. Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Valley of the Kings. p. 162. Thames & Hudson. 1997. (Reprint) ISBN 0-500-05080-5

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Reeves, Nicholas. Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Valley of the Kings. p. 52-53. Thames & Hudson. 1997. (Reprint) ISBN 0-500-05080-5

References

- Reeves, N & Wilkinson, R.H. The Complete Valley of the Kings, 1996, Thames and Hudson, London

- Siliotti, A. Guide to the Valley of the Kings and to the Theban Necropolises and Temples, 1996, A.A. Gaddis, Cairo

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to KV2. |

- Theban Mapping Project: KV2 - Includes description, images, and plans of the tomb.

| ||||||||||||||||||||