Kālidāsa

| Kālidāsa | |

|---|---|

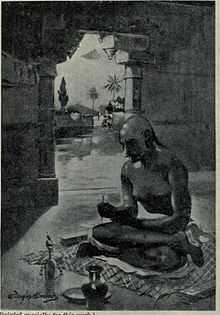

Kalidasa inditing the cloud Messenger, A.D. 375 | |

| Born | 4th century AD |

| Died |

5th century AD Gupta Empire, possibly in Ujjain or Sri Lanka |

| Occupation | Playwright and poet |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Ethnicity | Indian |

| Genre | Sanskrit drama, Classical literature |

| Subject | Epic poetry, Hindu Puranas |

| Notable works | Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Raghuvaṃśa, Meghadūta, Vikramōrvaśīyam, Kumārasambhava |

| Spouse | Said to have been married to a princess; her name was Vidyotama. |

Kālidāsa ("servant of Kali" Sanskrit: कालिदास) was a Classical Sanskrit writer, widely regarded as the greatest poet and dramatist in the Sanskrit language. His floruit cannot be dated with precision, but most likely falls within the 5th century AD.[1]

His plays and poetry are primarily based on the Hindu Puranas.

Early life

Scholars have speculated that Kālidāsa may have lived either near the Himalayas, or in the vicinity of Ujjain, or in Kalinga. The three speculations are based respectively on Kālidāsa's detailed description of the Himalayas in his Kumārasambhava, the display of his love for Ujjain in Meghadūta, and his highly eulogistic descriptions of Kalingan emperor Hemāngada in Raghuvaṃśa (sixth sarga).

But some scholars tend to describe him as a Kashmiri[2][3][4] since the pioneering research done by Lakshmi Dhar Kalla (1891-1953) in his continuously re-edited book The birth-place of Kalidasa, with notes, references and appendices (1926), saying that, far from being contradictory, these facts just show that he was born in Kashmir (based on topographic descriptions, rural folklore, the region's fauna and flora, ... only local populations could know) but moved for diverse reasons souther and sought the patronage of local rulers to prosper.

It is believed that he was from humble origin, married to princess and challenged by his wife, studied poetry to become great poet.[5] Some believe that he visited Kumaradasa, the king of Ceylon and, because of some treachery, Kalidasa was murdered there.[5] His wife's name was Vidyotama.

Period

His period was linked to the reign of one Vikramaditya. And Chandraguptha II (380 CE – 415 CE) and Skandagupta (455 CE – 480 CE), were titled Vikramaditya and Kalidasa's living period is linked to their reign.[6] It was also argued that Kalidasa lived in first century B.C. during the period of another Vikramaditya of Ujjain, but now it is generally accepted that Kalidasa's period falls between 5th and 6th Century C.E.[7] His name, along with poet Bharavi's name, is mentioned in a stone inscription dated 634 C.E. found at Aihole, located in present day Karnataka.[8]

Works

Plays

Kālidāsa wrote three plays. Among them, Abhijñānaśākuntalam ("Of Shakuntala recognised by a token") is generally regarded as a masterpiece. It was among the first Sanskrit works to be translated into English, and has since been translated into many languages.[9]

- Mālavikāgnimitram ("Mālavikā and Agnimitra") tells the story of King Agnimitra, who falls in love with the picture of an exiled servant girl named Mālavikā. When the queen discovers her husband's passion for this girl, she becomes infuriated and has Mālavikā imprisoned, but as fate would have it, Mālavikā is in fact a true-born princess, thus legitimizing the affair.

- Abhijñānaśākuntalam ("Of Shakuntala recognised by a token") tells the story of King Dushyanta who, while on a hunting trip, meets Shakuntalā, the adopted daughter of a sage, and marries her. A mishap befalls them when he is summoned back to court: Shakuntala, pregnant with their child, inadvertently offends a visiting sage and incurs a curse, by which Dushyanta will forget her completely until he sees the ring he has left with her. On her trip to Dushyanta's court in an advanced state of pregnancy, she loses the ring, and has to come away unrecognized. The ring is found by a fisherman who recognizes the royal seal and returns it to Dushyanta, who regains his memory of Shakuntala and sets out to find her. After more travails, they are finally reunited.

- Vikramōrvaśīyam ("Pertaining to Vikrama and Urvashi") tells the story of mortal King Pururavas and celestial nymph Urvashi who fall in love. As an immortal, she has to return to the heavens, where an unfortunate accident causes her to be sent back to the earth as a mortal with the curse that she will die (and thus return to heaven) the moment her lover lays his eyes on the child which she will bear him. After a series of mishaps, including Urvashi's temporary transformation into a vine, the curse is lifted, and the lovers are allowed to remain together on the earth.

Poems

Minor poems

Kālidāsa also wrote two khandakavyas (minor poems):

- Ṛtusaṃhāra describes the six seasons by narrating the experiences of two lovers in each of the seasons.[N 1]

- Meghadūta or Meghasāndesa is the story of a Yaksha trying to send a message to his lover through a cloud. Kalidasa set this poem to the 'mandākrānta' meter known for its lyrical sweetness. It is one of Kalidasa's most popular poems and numerous commentaries on the work have been written.

Translations

Montgomery Schuyler, Jr. published a bibliography of the editions and translations of the drama Shakuntala while preparing his work "Bibliography of the Sanskrit Drama".[N 2][10] Schuyler later completed his bibliography series of the dramatic works of Kālidāsa by compiling bibliographies of the editions and translations of Vikramorvaçī and Mālavikāgnimitra.[11]

Later culture

Many scholars have written commentaries on the works of Kālidāsa. Among the most studied commentaries are those by Kolāchala Mallinātha Suri, which were written in the 15th century during the reign of the Vijayanagar king, Deva Rāya II. The earliest surviving commentaries appear to be those of the 10th-century Kashmirian scholar Vallabhadeva.[12] Eminent Sanskrit poets like Bāṇabhaṭṭa, Jayadeva and Rajasekhara have lavished praise on Kālidāsa in their tributes. A well-known Sanskrit verse ("Upamā Kālidāsasya...") praises his skill at upamā, or similes. Anandavardhana, a highly revered critic, considered Kālidāsa to be one of the greatest Sanskrit poets ever. Of the hundreds of pre-modern Sanskrit commentaries on Kālidāsa's works, only a fraction have been contemporarily published. Such commentaries show signs of Kālidāsa's poetry being changed from its original state through centuries of manual copying, and possibly through competing oral traditions which ran alongside the written tradition.

Kālidāsa's Abhijñānaśākuntalam was one of the first works of Indian literature to become known in Europe. It was first translated to English and then from English to German, where it was received with wonder and fascination by a group of eminent poets, which included Herder and Goethe.[13]

Willst du die Blüthe des frühen, die Früchte des späteren Jahres,

Willst du, was reizt und entzückt, willst du was sättigt und nährt,

Willst du den Himmel, die Erde, mit Einem Namen begreifen;

Nenn’ ich, Sakuntala, Dich, und so ist Alles gesagt.—GoetheWouldst thou the young year's blossoms and the fruits of its decline

And all by which the soul is charmed, enraptured, feasted, fed,

Wouldst thou the earth and heaven itself in one sole name combine?

I name thee, O Sakuntala! and all at once is said.—translation by E. B. Eastwick

"Here the poet seems to be in the height of his talent in representation of the natural order, of the finest mode of life, of the purest moral endeavor, of the most worthy sovereign, and of the most sober divine meditation; still he remains in such a manner the lord and master of his creation."—Goethe, quoted in Winternitz[14]

Kālidāsa's work continued to evoke inspiration among the artistic circles of Europe during the late 19th century and early 20th century, as evidenced by Camille Claudel's sculpture Shakuntala.

Koodiyattam artist and Natya Shastra scholar Māni Mādhava Chākyār (1899–1990) choreographed and performed popular Kālidāsā plays including Abhijñānaśākuntala, Vikramorvaśīya and Mālavikāgnimitra.

The Kannada films Mahakavi Kalidasa (1955), featuring Honnappa Bagavatar, B. Sarojadevi and later Kaviratna Kalidasa (1983), featuring Rajkumar and Jayaprada,[15] were based on the life of Kālidāsa. V. Shantaram made the Hindi movie Stree (1961) based on Kālidāsa's Shakuntala. R.R. Chandran made the Tamil movie Mahakavi Kalidas (1966) based on Kālidāsa's life. Chevalier Nadigar Thilagam Sivaji Ganesan played the part of the poet himself. Mahakavi Kalidasu (Telugu, 1960) featuring Akkineni Nageswara Rao[16] was similarly based on Kālidāsa's life and work.

Surendra Verma's Hindi play Athavan Sarga, published in 1976, is based on the legend that Kālidāsa could not complete his epic Kumārasambhava because he was cursed by the goddess Parvati, for obscene descriptions of her conjugal life with Lord Shiva in the eighth canto. The play depicts Kālidāsa as a court poet of Chandragupta who faces a trial on the insistence of a priest and some other moralists of his time.

Asti Kashchid Vagarthiyam is a five-act Sanskrit play written by Krishna Kumar in 1984. The story is a variation of the popular legend that Kālidāsa was mentally challenged at one time and that his wife was responsible for his transformation. Kālidāsā, a mentally challenged shepard, is married to Vidyottamā, a learned princess, through a conspiracy. On discovering that she has been tricked, Vidyottamā banishes Kālidāsa, asking him to acquire scholarship and fame if he desires to continue their relationship. She further stipulates that on his return he will have to answer the question, Asti Kashchid Vāgarthah" ("Is there anything special in expression?"), to her satisfaction. In due course, Kālidāsa attains knowledge and fame as a poet. Kālidāsa begins Kumārsambhava, Raghuvaṃśa and Meghaduta with the words Asti ("there is"), Kashchit ("something") and Vāgarthah ("speech").

Bishnupada Bhattacharya's "Kalidas o Robindronath" is a comparative study of Kalidasa and the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Ashadh Ka Ek Din is a play based on fictionalized elements of Kalidasa life.

Further reading

- K. D. Sethna. Problems of Ancient India, p. 79-120 (chapter: "The Time of Kalidasa"), 2000 New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-026-7 (about the dating of Kalidasa)

- V. Venkatachalam. Fresh light on Kalidasa's historical perspective, Kalidasa Special Number (X), The Vikram, 1967, pp. 130–140.

See also

References

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Kalidasa (Indian author)".

- ↑ Ram Gopal (1 January 1984). Kālidāsa: His Art and Culture. Concept Publishing Company. p. 3.

- ↑ P. N. K. Bamzai (1 January 1994). Culture and Political History of Kashmir 1. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-81-85880-31-0.

- ↑ M. K. Kaw (1 January 2004). Kashmir and It's People: Studies in the Evolution of Kashmiri Society. APH Publishing. p. 388. ISBN 978-81-7648-537-1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "About Kalidasa". Kalidasa Academi. Retrieved 21 July 2013.

- ↑ Gaurīnātha Śāstrī 1987, p. 78

- ↑ Gaurīnātha Śāstrī 1987, p. 77

- ↑ Gaurīnātha Śā ihihhistrī 1987, p. 80

- ↑ Kalidas, Encyclopedia Americana

- ↑ Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1901). "The Editions and Translations of Çakuntalā". Journal of the American Oriental Society 22: 237–248. JSTOR 592432.

- ↑ Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1902). "Bibliography of Kālidāsa's Mālavikāgnimitra and Vikramorvaçī". Journal of the American Oriental Society 23: 93–101. JSTOR 592384.

- ↑ Dominic Goodall and Harunaga Isaacson, The Raghupañcikā of Vallabhadeva, Volume 1, Groningen, Egbert Forsten, 2004.

- ↑ Maurice Winternitz and Subhadra Jha, History of Indian Literature

- ↑ Maurice Winternitz; Moriz Winternitz (1 January 2008). History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 238. ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4.

- ↑ Kavirathna Kalidasa (1983) Kannada Film at IMDb

- ↑ Mahakavi Kalidasu, 1960 Telugu film at IMDb.

Notes

- ↑ Ṛtusaṃhāra was translated into Tamil by Muhandiram T. Sathasiva Iyer

- ↑ It was later published as the third volume of the 13-volume Columbia University Indo-Iranian Series, published by the Columbia University Press in 1901-32 and edited by A. V. Williams Jackson

Bibliography

- Raghavan, V. (January–March 1968). "A Bibliography of translations of Kalidasa's works in Indian Languages". Indian Literature 11 (1): 5–35. JSTOR 23329605.

- Gaurīnātha Śāstrī (1987). A Concise History of Classical Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0027-4.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Kālidāsa |

- Kalidasa: Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works by Arthur W. Ryder

- Biography of Kalidasa

- Works by Kalidasa at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Kālidāsa at Internet Archive

- Clay Sanskrit Library publishes classical Indian literature, including the works of Kalidasa with Sanskrit facing-page text and translation. Also offers searchable corpus and downloadable materials.

- Kalidasa at The Online Library of Liberty

- Kālidāsa at the Internet Movie Database

| ||||||||||

|