Jurij Vega

| Jurij Vega | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

March 23, 1754 Zagorica pri Dolskem, Slovenia |

| Died |

September 26, 1802 (aged 48) Nußdorf near Vienna, Austria |

Baron Jurij Bartolomej Vega (also correct Veha; official Latin: Georgius Bartholomaei Vecha; German: Georg Freiherr von Vega) (born Vehovec, March 23, 1754 – September 26, 1802) was a Slovene mathematician, physicist and artillery officer.

Early life

Born to a farmer's family[1] in the small village of Zagorica east of Ljubljana in Slovenia, Vega was 6 years old when his father Jernej Veha died. Vega was educated first in Moravče and later attended high school for six years (1767–1773) in Ljubljana, studying Latin, Greek, religion, German, history, geography, science, and mathematics. At that time there were about 500 students there. He was a schoolfellow of Anton Tomaž Linhart, a Slovenian writer and historian. Vega completed high school when he was 19, in 1773. After completing Lyceum in Ljubljana he became a navigational engineer. Tentamen philosophicum, a list of questions for his comprehensive examination, was preserved and is available in the Mathematical Library in Ljubljana. The problems cover logic, algebra, metaphysics, geometry, trigonometry, geodesy, stereometry, geometry of curves, ballistics, and general and special physics.

Military service

Vega left Ljubljana five years after graduation and entered military service in 1780 as a professor of mathematics at the Artillery School in Vienna. At that time he started to sign his last name as Vega and no longer Veha. When Vega was 33 he married Josefa Svoboda (Jožefa Swoboda) (1771–1800), a Czech noble from České Budějovice who was 16 at that time.

Vega participated in several wars. In 1788 he served under Austrian Imperial Field-Marshal Ernst Gideon von Laudon (1717–1790) in a campaign against the Turks at Belgrade. His command of several mortar batteries contributed considerably to the fall of the Belgrade fortress. Between 1793 and 1797 he fought French Revolutionaries under the command of Austrian General Dagobert-Sigismond de Wurmser (1724–1797) with the European coalition on the Austrian side. He fought at Fort Louis, Mannheim, Mainz, Wiesbaden, Kehl, and Dietz. In 1795 he had two 30-pound (14 kilogram) mortars cast, with conically drilled bases and a greater charge, for a firing range up to 3000 metres (3300 yards). The old 60 lb (27 kg) mortars had a range of only 1800 m (2000 yd).

In September 1802 Vega was reported missing. After a few days' search his body was found. The police report concluded that it was an accident. However, the true cause of his death remains a mystery, but it is believed that he died on 26 September 1802 in Nußdorf on the Danube, near the Austrian capital, Vienna. There is a well-backed theory about his death: he loved horses, and apparently he found out a miller owned a magnificent one. When he went to the miller to negotiate about the price, the miller, upon seeing his Lord and military insignia, took interest in the money he was carrying with him, murdered him; one of Vega's tools (compass) was found in the mill one year after his disappearance and it had "J V" initials on it.

Mathematical accomplishments

Vega published a series of books of logarithm tables. The first one appeared in 1783. Much later, in 1797 it was followed by a second volume that contained a collection of integrals and other useful formulae. His Handbook, which was originally published in 1793, was later translated into several languages and appeared in over 100 issues. His major work was Thesaurus Logarithmorum Completus (Treasury of all Logarithms) that was first published 1794 in Leipzig. This table was actually based on Adriaan Vlacq's tables, but corrected a number of errors and extended the logarithms of trigonometric functions for the small angles. An engineer, Franc Allmer, honourable senator of the Technical university of Graz, has found Vega's logarithmic tables with 10 decimal places in the Museum of Carl Friedrich Gauss in Göttingen. Gauss used this work frequently and he has written in it several calculations. Gauss has also found some of Vega's errors in the calculations in the range of numbers, of which there are more than a million. A copy of Vega's Thesaurus belonging to the private collection of the British mathematician and computing pioneer Charles Babbage (1791–1871) is preserved at the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh.

Over the years Vega wrote a four volume textbook Vorlesungen über die Mathematik (Lectures about Mathematics). Volume I appeared in 1782 when he was 28 years old, Volume II in 1784, Volume III in 1788 and Volume IV in 1800. His textbooks also contain interesting tables: for instance, in Volume II one can find closed form expressions for sines of multiples of 3 degrees, written in a form easy to work with.

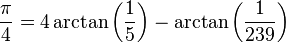

Vega wrote at least six scientific papers. On August 20, 1789 Vega achieved a world record when he calculated pi to 140 places, of which the first 126 were correct. This calculation he proposed to the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg (Санкт Петербург) in the booklet V. razprava (The fifth discussion), where he had found with his calculating method an error on the 113th place from the estimation of Thomas Fantet de Lagny (1660–1734) from 1719 of 127 places. Vega retained his record 52 years until 1841 and his method is mentioned still today. His article was not published by the Academy until six years later, in 1795. Vega had improved John Machin's formula from 1706:

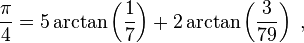

with his formula, which is equal to Euler's formula from 1755:

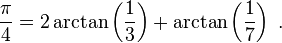

and which converges faster than Machin's formula. He had checked his result with the similar Hutton's formula:

He had developed the second term in the series only once.

Although he worked in the subjects of ballistics, physics and astronomy, his major contributions are to the mathematics of the second half of the 18th century.

In 1781 Vega tried to push further his idea in the Austrian Habsburg monarchy about the usage of the decimal metric system of units. His idea was not accepted, but it was introduced later under the emperor Franz Josef I in 1871.

Vega was a member of the Academy of Practical Sciences in Mainz, the Physical and Mathematical Society of Erfurt, the Bohemian Scientific Society in Prague, and the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. He was also an associate member of the British Scientific Society in Göttingen. He was awarded the Order of Maria Theresa on May 11, 1796. In 1800 Vega obtained a title of hereditary baron including the right to his own coat of arms.

Things referencing Jurij Vega

Post of Slovenia has issued a stamp honouring Vega and the National Bank of Slovenia has issued a 50 tolar banknote in his honour.

Vega (crater) on the Moon is named after him.

An asteroid 14966 Jurijvega, discovered on July 30, 1997, is named after him. Also, a free open-source physics library for 3D deformable object simulation Vega FEM has been named after Vega.

The Astronomical Society Vega - Ljubljana of Slovenia is named after both Jurij Vega and the star Vega. The star, though, is not named after Jurij Vega and the name is much older.

See also

References

- ↑ Šuman, Josef; Simonič, Franz. Die Völker Oesterreich-ungarns. Ethnographische und culturhistorische Schilderungen, Vol. 10., K. Prochaska Press, 1881., p. 182. (German)

Der Bauernsohn Georg Vega, geboren 1754 zu Zagoric in der Moräutscher Pfarre (Moravče), betrat unter Kaiser Josef seine Ruhmesbahn.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jurij Vega. |

- Jurij Vega on the Slovenian 50 Tolars banknote.

- University of St Andrews' page on Vega: http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Mathematicians/Vega.html

- Vega and his time

- Vega FEM library

|