Julian of Norwich

| Julian of Norwich | |

|---|---|

Julian of Norwich, as depicted in the church of Ss Andrew and Mary, Langham, Norfolk | |

| Julian of Norwich, Lady Julian of Norwich | |

| Born |

c. 8 November 1342 Norfolk |

| Died |

c. 1416 Norwich |

| Venerated in |

Anglican Communion Lutheran Church |

| Major shrine | Church of St Julian, Norwich |

| Feast | 8 May or 13 May |

| Major works | Revelations of Divine Love |

| Part of a series on | ||||||||

| Christian mysticism | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

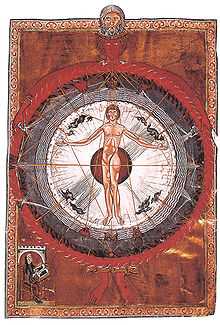

| ||||||||

|

Theologies · Philosophies |

||||||||

|

People by era or century | ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

Contemporary Papal views |

||||||||

Julian of Norwich (c. 8 November 1342 – c. 1416) was an English anchoress who is regarded as an important Christian mystic. She is venerated in the Anglican and Lutheran churches, but has never been canonised or beatified. Written around 1395, her work, Revelations of Divine Love, is the first book in the English language known to have been written by a woman.[1]

Personal life

Very little is known about Julian's life. Even her name is unknown; the name "Julian" simply derives from the fact that her anchoress's cell was built onto the wall of the Church of St Julian in Norwich. Her writings indicate that she was probably born around 1342 and died around 1416.[2][3][4] She may have been from a privileged family that lived in Norwich, or nearby. Norwich was at the time the second largest city in England. Plague epidemics were rampant during the 14th century and, according to some scholars, Julian may have become an anchoress whilst still unmarried or, having lost her family in the Plague, as a widow.[5] Becoming an anchoress may have served as a way to quarantine her from the rest of the population. There is scholarly debate as to whether Julian was a nun in a nearby convent or even a laywoman.[5]

When she was 30 and living at home, Julian suffered from a severe illness. Whilst apparently on her deathbed, Julian had a series of intense visions of Jesus Christ, which ended by the time she recovered from her illness on 13 May 1373.[6] Julian wrote about her visions immediately after they had happened (although the text may not have been finished for some years), in a version of the Revelations of Divine Love now known as the Short Text; this narrative of 25 chapters is about 11,000 words long.[7] It is believed to be the earliest surviving book written in the English language by a woman.[8]

Twenty to thirty years later, perhaps in the early 1390s, Julian began to write a theological exploration of the meaning of the visions, known as The Long Text, which consists of 86 chapters and about 63,500 words.[9] This work seems to have gone through many revisions before it was finished, perhaps in the first or even second decade of the fifteenth century.[7]

The English mystic Margery Kempe, who was the author of the first known autobiography written in England, mentioned going to Norwich to speak with her in around 1414.[10]

The Norwich Benedictine and Cardinal, Adam Easton, may have been Julian of Norwich's spiritual director and edited her Long Text Showing of Love. Birgitta of Sweden's spiritual director, Alfonso Pecha, the Bishop Hermit of Jaen, edited her Revelationes. Catherine of Siena's confessor and executor was William Flete, the Cambridge-educated Augustinian Hermit of Lecceto. Easton's Defense of St Birgitta echoes Alfonso of Jaen's Epistola Solitarii and William Flete's Remedies against Temptations, all of which are referred to in Julian's text.[11]

Revelations of Divine Love

The Short Text survives in only one manuscript, the mid-15th century Amherst Manuscript, which was copied from an original written in 1413 in Julian’s own lifetime.[12] The Short Text does not appear to have been widely read, and it was not edited until 1911.[7]

The Long Text appears to have been slightly better known, but still does not seem to have been widely circulated in late medieval England. The one surviving manuscript from this period is the mid- to late-fifteenth century Westminster Manuscript, which contains a portion of the Long Text (not naming Julian as its author), refashioned as a didactic treatise on contemplation.[13] The surviving manuscripts of the whole Long Text fall into two groups, with slightly different readings. On the one hand, there exists the late sixteenth century Brigittine Long Text manuscript, produced in exile in the Antwerp region, and now known as the Paris Manuscript. The other set of readings may be found in two manuscripts, now in the British Library's Sloane Collection.[14] It is believed these nuns had an original, perhaps a holograph, manuscript of the Long Text, written in Julian's Norwich dialect.[14] which were written out and preserved in the Cambrai and Paris houses of the English Benedictine nuns in exile in the mid-seventeenth century.[15]

The first printed version of the Revelations was edited by the Benedictine Serenus Cressy in 1670, and was reprinted in 1843, 1864 and again in 1902. Modern interest in the text increased with the 1877 publication of a new edition of the Long Text by Henry Collins. An important moment was the publication of Grace Warrack's 1901 version of the book, with its "sympathetic informed introduction" and modernised language, which introduced most early 20th century readers to Julian's writings.[16] Following the publication of the Warrack edition, Julian's name spread rapidly and she became a topic in many lectures and writings. Many editions of the works have been published in the last forty years (see below for further details), with translations into French (five times), German (four times), Italian, Finnish, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, Catalan, Greek and Russian.[13]

Revelations is a celebrated work in Catholicism and Anglicanism because of the clarity and depth of Julian's visions of God.[17] Julian of Norwich is now recognised as one of England's most important mystics.[18]

Theology

Julian of Norwich lived in a time of turmoil, but her theology was optimistic and spoke of God's love in terms of joy and compassion, as opposed to law and duty. For Julian, suffering was not a punishment that God inflicted, as was the common understanding. She believed that God loved everyone and wanted to save them all. Popular theology, magnified by catastrophic contemporary events such as the Black Death and a series of peasant revolts, asserted that God punished the wicked. Julian suggested a more merciful theology, which some[19] say leaned towards universal salvation.[20] She believed that behind the reality of hell is a greater mystery of God's love. In modern times, she has been classified[20] as a proto-universalist, although she did not claim more than hope that all might be saved.[21]

Although Julian's views were not typical, the authorities might not have challenged her theology because of her status as an anchoress. A lack of references to her work during her own time may indicate that the religious authorities did not count her worthy of refuting, since she was a woman. Her theology was unique in three aspects: her view of sin; her belief that God is all-loving and without wrath; and her view of Christ as mother.[20]

Julian believed that sin was necessary because it brings someone to self-knowledge, which leads to acceptance of the role of God in their life.[22] She taught that humans sin because they are ignorant or naive, and not because they are evil, the reason commonly given by the mediaeval church to explain sin.[23] Julian believed that to learn we must fail, and to fail we must sin. She also believed that the pain caused by sin is an earthly reminder of the pain of the passion of Christ and that as people suffer as Christ did they will become closer to him by their experiences.

Julian saw no wrath in God. She believed wrath existed in humans, but that God forgives us for this. She wrote, "For I saw no wrath except on man's side, and He forgives that in us, for wrath is nothing else but a perversity and an opposition to peace and to love."[24] Julian believed that it was inaccurate to speak of God's granting forgiveness for sins, because forgiving would mean that committing the sin was wrong. She preached that sin should be seen as a part of the learning process of life, not a malice that needed forgiveness. She wrote that God sees us as perfect and waits for the day when human souls mature so that evil and sin will no longer hinder us.[25]

Julian's belief in God as mother was controversial. According to Julian, God is both our mother and our father. As Caroline Walker Bynum showed, this idea was also developed by Bernard of Clairvaux and others from the 12th century onward.[26] Some scholars think this is a metaphor rather than a literal belief or dogma. For example, in her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving and merciful. F. Beer asserted that Julian believed that the maternal aspect of Christ was literal and not metaphoric: Christ is not like a mother, he is literally the mother.[27] Julian believed that the mother's role was the truest of all jobs on earth. She emphasised this by explaining how the bond between mother and child is the only earthly relationship that comes close to the relationship a person can have with Jesus.[28] She also connected God with motherhood in terms of "the foundation of our nature's creation", "the taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins" and "the motherhood at work". She wrote metaphorically of Jesus in connection with conception, nursing, labour and upbringing, but saw him as our brother as well.

Legacy

The 20th-century poet T.S. Eliot incorporated the saying that "…All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well", as well as Julian's "the ground of our beseeching" from the 14th Revelation, into Little Gidding, the fourth of his Four Quartets:[29]

- Whatever we inherit from the fortunate

- We have taken from the defeated

- What they had to leave us—a symbol:

- A symbol perfected in death.

- And all shall be well and

- All manner of thing shall be well

- By the purification of the motive

- In the ground of our beseeching.

Julian's feast day in the Roman Catholic tradition is on 13 May.[5] In the Anglican and Lutheran traditions, her feast day is on 8 May.

In 1981 Sydney Carter wrote the song "Julian of Norwich" (sometimes called "The Bells of Norwich"), based on words of Julian.

The University of East Anglia honoured Julian in 2013 by naming the new study centre (with 280 seat lecture theatre, seminar rooms, and high ecological standards) the "Julian Study Centre."[30]

Each year, beginning in 2013, there has been a week-long celebration of Julian of Norwich in her home city, Norwich England. With concerts, lectures, workshops, and tours, the week aims to educate all interested people about Julian of Norwich, presenting Julian as a cultural, historical, literary, spiritual, and religious figure of international significance.

See also

- Sydney Carter, author of a 1981 song about Julian

- Visions of Jesus and Mary

- List of Catholic saints

References

- ↑ "10 things to know about Norwich" (PDF). UNESCO. November 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- ↑ Ritchie, Ronald, Joy, Kate (2001). Available Means: An Anthology of Women's Rhetoric. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 25–28.

- ↑ Beer, F., Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, page 130. Boydell Press, 1992

- ↑ She was certainly still alive in 1413, since the introduction to the Short Text written in the Amherst Manuscript, which is preserved in the British Library, names Julian and refers to her as alive; Margery Kempe visited her around 1414, indicating she was still alive then.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bhattacharji, Santha. "Julian of Norwich (1342 – c. 1416)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online Ed. Oxford: OUP. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ "Julian of Norwich". Encyclopædia Britannica Profiles. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Bernard McGinn, The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism, (New York: Herder & Herder, 2012), p425.

- ↑ Julian of Norwich. Showings (Paulist Press). 1978.

- ↑ Jantzen, G. Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian, pgs. 4–5. Paulist Press, 1988

- ↑ "The Book of Margery Kempe, Book I, Part I". The Book of Margery Kempe. TEAMS Middle English Texts. 1996. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- ↑ Julia Bolton Holloway, Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of Norwich and Adam Easton, O.S.B. Analecta Cartusiana, 2008

- ↑ The manuscript is now in the British Library.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Bernard McGinn, The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism, (New York: Herder & Herder, 2012), p426.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Crampton. The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, pg. 17. Western Michigan University, 1993

- ↑ All the Julian manuscripts have been edited diplomatically by Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P. and Julia Bolton Holloway in their 2001 edition (Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo).

- ↑ Crampton. The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, pg. 18. Western Michigan University, 1993

- ↑ "Julian of Norwich". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- ↑ Pelphrey, B. Christ Our Mother: Julian of Norwich, pg. 14. Michael Glazier Inc., 1989

- ↑ http://www.christianhistoryinstitute.org/incontext/article/julian/

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2

- ↑ John Hick, The Fifth Dimension: An Exploration of the Spiritual Realm, Oxford: One World, 2004.

- ↑ Beer, F: Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, pg. 143. Boydell Press, 1992

- ↑ Beer, F: Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, pg. 144. Boydell Press, 1992

- ↑ Revelations of Divine Love, p. 45. ed., D.S. Brewer, 1998

- ↑ Revelations of Divine Love, p. 50. D.S. Brewer, 1998

- ↑ Bynum, Caroline Walker (1982). Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Beer, F: Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, p. 152. Boydell Press, 1992

- ↑ Beer, F: Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages, p. 155. Boydell Press, 1992

- ↑ Newman, Barbara (2011). "Eliot's Affirmative Way: Julian of Norwich, Charles Williams, and Little Gidding". Modern Philology 108: 427–61. doi:10.1086/658355.

- ↑ https://www.uea.ac.uk/mac/comm/media/press/2013/June/julian-study-centre

Modern editions and translations

Editions:

- The Writings of Julian of Norwich, ed. Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. Penn State University Press, 2006. [An edition and commentary of both the Short Text and Long Text. The Long Text is here generally based on the Paris manuscript]

- Denise N. Baker (2005), of the Long Text, based on the Paris manuscript

- Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translation, ed. Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P., and Julia Bolton Holloway. Florence: SISMEL Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2001. ISBN 88-8450-095-8. [A “quasi-fascimile” of each version of the Showing of Love in the Westminster, Paris, Sloane and Amherst Manuscripts.]

- The Shewings of Julian of Norwich, ed. Georgia Crampton. (Kalamazoo, MI: Western Michigan University, 1994). [Of the Long Text, based largely on one of the two Sloane manuscripts.]

- Colledge, Edmund, and James Walsh, Julian of Norwich: Showings, Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1978. (a fully annotated edition of both the Short Text and Long Text, basing the latter on the Paris manuscript but using alternative readings from the Sloane manuscript when these were judged to be superior)

Translations:

- Fr. John-Julian, "The Complete Julian of Norwich". Orleans,MA; Paraclete Press, 2009

- Dutton, Elisabeth. A Revelation of Love (Introduced, Edited & Modernized). Rowman & Littlefield, 2008

- Showing of Love, Trans. Julia Bolton Holloway. Collegeville: Liturgical Press; London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. [Collates all the extant manuscript texts]

- Wolters, Clifton, Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love, (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966) (the Long Text, based on the Sloane manuscripts)

Bibliography

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Dutton, E.M. (2008). Julian of Norwich: The Influence of Late-medieval Devotional Compilations. Boydell & Brewer.

- Holloway, J.B., Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of Norwich and Adam Easton, O.S.B., Analecta Cartusiana, 2008; ISBN 978-3-902649-01-0.

- Jantzen, Grace. Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian. London: SPCK. 1987.

- McAvoy, L. H., ed., A Companion to Julian of Norwich, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 2008.

- McEntire, S., ed., Julian of Norwich: A Book of Essays, Taylor & Francis, 1998.

- Turner, D., Julian of Norwich, Theologian, Yale University Press, 2011

- Nicholas Watson (1992). "The Trinitarian Hermeneutic in Julian of Norwich's Revelation of Love". In Glasscoe, M. The Medieval Mystical Tradition in England V: Papers read at Dartington Hall, July 1992. D.S. Brewer. pp. 79–100.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Julian of Norwich |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Julian of Norwich. |

- "Julian of Norwich", Luminarium Website, Life, works, essays

- "Juliana of Norwich", Catholic Encyclopedia

- "Julian of Norwich", Umilta Website, Life, manuscripts, texts and contexts

- Works by or about Julian of Norwich in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

|