Jozef Tiso

| Jozef Tiso | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Slovakia | |

| In office 26 October 1939 – 3 April 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Office created |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 October 1887 Bytča (Nagybiccse) Trencsén County, Kingdom of Hungary, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 18 April 1947 (aged 59) Bratislava, Czechoslovakia |

| Political party | Slovak People's Party |

| Profession | Politician, Cleric, Roman Catholic priest |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Jozef Tiso (13 October 1887 – 18 April 1947) was a Slovak Roman Catholic priest, and a leading politician of the Slovak People's Party. Between 1939 and 1945, Tiso was the head of the 1939–45 First Slovak Republic, a satellite state of Nazi Germany. After the end of World War II, Tiso was convicted and hanged for treason.

Early life

Tiso was born in Bytča to Slovak parents in what was then the Trencsén County of the Kingdom of Hungary, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Bishop of Nitra, Imre Bende, offered Tiso a chance to study for the priesthood, and, in 1911, Tiso graduated from the prestigious Pázmáneum in Vienna.[1] His early ministry was spent as an assistant priest in three parishes in today's Slovakia. After brief frontline service as a field curate in World War I, he was appointed as the Spiritual Director of the Nitra seminary by Bende's successor, Vilmos Batthyány.[2] Tiso was also active at this time as a school teacher and journalist. His articles for the local paper would later be controversial because of their strong support for the Hungarian war cause. During this period he frequently used the Hungarian form of his name, Tiszó József.[3]

With the collapse of Austria-Hungary and the creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918, Tiso suddenly embraced politics as a career, at the same time declaring himself in public as a Slovak.[4] Within a few weeks, he had joined the Slovak People's Party. In 1918 and 1919, he was editor of a newspaper, Nitra (Nyitra in its Hungarian edition), in which he made clear his highly antisemitic opinions.[5] In 1921 Tiso was appointed monsignor by the Vatican, although this appointment lapsed with the later death of Pope Benedict XV.[6] From 1921 to 1923, he served as the secretary to the new Slovak bishop of Nitra, Karol Kmeťko. During the same period, nationalist political agitation earned Tiso two convictions for incitement, one of which resulted in a short incarceration. Displeased, Kmeťko dropped him as secretary in 1923, but retained him as a Professor of Theology. In 1924, Tiso left Nitra to become parish priest and then dean of Bánovce nad Bebravou.[7] He was to remain an active priest throughout his political career.[8]

Political rise

Tiso became one of the leaders of the Slovak People's Party (otherwise known as the Ľudáks), which had been founded by Father Andrej Hlinka in 1913, while Austria-Hungary still ruled Slovakia. It sought Slovak autonomy within a Czechoslovak framework.[9] The extreme-nationalist lawyer Vojtech Tuka headed the party's radical wing, which during the 1930s moved steadily closer to National Socialism, complete with its Hlinka Guard paramilitary wing.[10]

Tiso first ran for parliament in 1920. Although the electoral results from his district were bright spots in what was otherwise a disappointing election for the Ľudáks, the party did not reward him with a legislative seat. Tiso, however, easily claimed one in the 1925 election, which also resulted in a breakthrough victory for the party. Until 1938, he was a fixture in the Czechoslovak parliament in Prague. From 1927 to 1929, despite a failed attempt to integrate the Ľudáks into the Czechoslovak polity, he also served as the Czechoslovak Minister of Health and Physical Education. Tiso was more inclined than Hlinka and Tuka to find compromises with other parties to form alliances, but for a decade after 1929 his initiatives were not successful.

Although Tiso seemed destined in the late 1920s to succeed Hlinka, he spent the 1930s instead competing for Hlinka's mantle with party radicals, most notably the rightist Karol Sidor - Tuka was in prison for much of this period for treason. In this context, Tiso, who had put aside much of the anti-Jewish rhetoric of his earlier journalistic activities, represented the moderate wing of the Ľudáks. However, he still upheld the 'separatist' Slovak policies of the party, strongly pro-Catholic and suspicious of Czech supremacy and socialism. When Hlinka died in 1938, Tiso quickly consolidated control of the Ľudák party.[11]

Slovak secession

In October 1938, Nazi Germany annexed and occupied the Sudetenland, the German-speaking parts of Czechoslovakia. By making an alliance with the Slovak Agrarian Party that committed the latter to Tiso's views on Slovak separatism, he became leader of the government of the resulting Slovak autonomous region.[12] In November 1938, Hungary, having never really accepted the separation of Slovakia from its control in 1918, took advantage of the situation and persuaded Germany and Italy to cede one third of Slovak territory to Hungary in the First Vienna Award. In the same month, all Czech or Slovak political parties in Slovakia (except for the Communists) voluntarily joined forces and set up the "Party of Slovak National Unity", which created the basis for the future authoritarian regime in Slovakia. In January 1939, the Slovak government prohibited all parties apart from the Party of Slovak National Unity and two parties of minority populations, the "German Party" and the "Unified Hungarian Party".

As part of their aim to dismantle the remaining Czechoslovak state, German representatives in February 1939 tried to persuade Tiso to declare Slovakia fully independent. During February 1939 Tiso secretly began direct meetings with the Austrian representative Arthur Seyss-Inquart, in which Tiso initially expressed doubts as to whether an independent Slovakia would be a viable entity. Eventually Czech security units occupied Slovakia and forced Tiso out of office on 9 March 1939.[13]

Tiso's nationalist feelings initially inhibited him from what appeared to be selling out his country to the Germans.[14] However, within a few days Hitler invited Tiso to Berlin, and offered assistance for Slovak nationhood.[15] Hitler threatened that if Slovakia did not immediately declare independence "under German protection", Hungary was preparing to annex the remaining territory of Slovakia. Under these circumstances, Tiso signed an agreement in Berlin (without the consent of the Slovak Assembly) and effectively presented it as a fait accompli at the Slovak Assembly which, on the initiative of the nationalist president of the assembly, Martin Sokol, endorsed a declaration of independence.[16] On 15 March, after coercing Hacha into asking for German protection, Germany occupied the Czech lands.

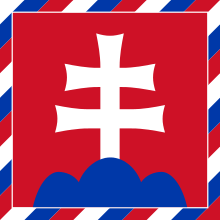

Slovakia became the Slovak Republic, a nominally independent state, but in fact a puppet state of Nazi Germany. Tiso was initially Prime Minister from 14 March 1939 until 26 October 1939. On 1 October 1939 Tiso became official president of the Slovak People's Party. On 26 October he became President of Slovakia and appointed Tuka as Prime Minister. After 1942, Tiso was also styled Vodca ("Leader"), an imitation in the national language of Führer.[10]

Anti-semitism and deportation of Jews

.jpg)

At a conference held in Salzburg, Austria on 28 July 1940, an agreement was reached to establish a National Socialist regime in Slovakia. Tuka attended the conference, as did Hitler, Tiso, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Alexander Mach (head of the Hlinka Guards), and Franz Karmasin, head of the local German minority. As a result of the conference, two state agencies were created to deal with "Jewish affairs".[17][18] The "Salzburg Summit" resulted in closer collaboration with Germany, and in Tuka and other political leaders increasing their powers at the expense of Tiso's original concept of a Catholic corporate state. The agreement called for dual command by the Slovak People’s Party and the Hlinka Guard (HSĽS), and also an acceleration in Slovakia's anti-Jewish policies. The Reich appointed Stormtrooper leader Manfred von Killinger as the German representative in Slovakia. Tiso however accepted these changes in subsequent conversation with Hitler.[19] SS Officer Dieter Wisliceny was dispatched to Slovakia to act as an 'adviser' on Jewish issues.[20] The Party under Tiso and Tuka's leadership aligned itself with Nazi policy with anti-Semitic legislation in Slovakia. The main act was the Jewish Code, under which Jews in Slovakia could not own any real estate or luxury goods, were excluded from public office and free occupations, could not participate in sport or cultural events, were excluded from secondary schools and universities, and were required to wear the star of David in public. Tiso himself had anti-Semitic views (as his earlier journalism made clear). Although there are dissenting opinions by modern politicians on his role in the Jewish deportations from Slovakia,[21] it is clear that, in line with his earlier anti-semitism, he welcomed and encouraged these actions, despite condemnation of the deportations from some Slovak bishops. In 1942 he gave a speech in Holíč in which he justified ongoing deportations of Slovak Jews; Hitler commented after this speech "It is interesting how this little Catholic priest Tiso is sending us the Jews!".[22]

In February 1942, the regime agreed to begin deportations of Jews and Slovakia became the first Nazi ally to agree to deportations.[23] The Nazis had asked for 20,000 young able-bodied Jews. Tiso hoped that compliance would aid in the return of 120,000 Slovak workers from Germany.[24] Later in 1942, amid Vatican protests as news of the fate of the deportees filtered back, and the German advance into Russia was halted, Slovakia became the first of Hitler's puppet states to shut down the deportations.[25] "By the end of June 1942, some 52,000 Slovak Jews had been deported, mainly to Auschwitz and to their death. Then, however, the deportations slowed to a standstill. The intervention of the Vatican, followed by the bribing of Slovak officials upon the initiative of a group of local Jews ["Working Group"] did eventually play a role ... That bribing the Slovaks contributed to a halt in the deportations for two years is most likely ...".[26]

Knowledge of the conditions at Auschwitz began to spread. Mazower wrote: "When the Vatican protested, the government responded with defiance: 'There is no foreign intervention which would stop us on the road to the liberation of Slovakia from Jewry', insisted President Tiso".[27] Distressing scenes at railway yards of deportees being beaten by Hlinka guards had spurred community protest, including from leading churchmen such as Bishop Pavol Jantausch.[28] The Vatican called in the Slovak ambassador twice to enquire what was happening in Slovakia. These interventions, wrote Evans, "caused Tiso, who after all was still a priest in holy orders, to have second thoughts about the programme".[29] Giuseppe Burzio and others reported to Tiso that the Germans were murdering the deported Jews. Tiso hesitated and then refused to deport Slovakia's 24,000 remaining Jews.[23] According to Mazower "Church pressure and public anger resulted in perhaps 20,000 Jews being granted exemptions, effectively bringing the deportations there to an end".[27]

When in 1943 rumours of further deportations emerged, the Papal Nuncio in Istanbul, Msgr. Angelo Roncalli (later Pope John XXIII) and Burzio helped galvanize the Holy See into intervening in vigorous terms. On 7 April 1943, Burzio challenged Tuka over the extermination of Slovak Jews. The Vatican condemned the renewal of the deportations on 5 May and the Slovakian episcopate issued a pastoral letter condemning totalitarianism and antisemitism on 8 May 1943.[9] "Tuka", wrote Evans, was "forced to backtrack by public protests, especially from the Church, which by this time had been convinced of the fate that awaited the deportees. Pressure from the Germans, including a direct confrontation between Hitler and Tiso on 22 April 1943, remained without effect."[29]

In August 1944, the Slovak National Uprising rose against the Tiso regime. German troops were sent to quell the rebellion and with them came security police charged with rounding up Slovakia's remaining Jews.[23] Burzio begged Tiso directly to at least spare Catholic Jews from transportation and delivered an admonition from the Pope: "the injustice wrought by his government is harmful to the prestige of his country and enemies will exploit it to discredit clergy and the Church the world over."[9] Tiso ordered the deporation of the nation's remaining Jews, who were sent to the Concentration Camps - most to Auschwitz.[29] Although the Germans allowed Tiso to remain in office, under their effective occupation his presidency was relegated to a mostly titular role as Slovakia lost whatever de facto independence it still had. During the 1944–1945 German occupation, another 13,500 Jews were deported and 5,000 imprisoned. Some were murdered in Slovakia itself, in particular at Kremnicka and Nemecká.

Trial and death

Tiso lost all remnants of power when the Soviet Army conquered the last parts of western Slovakia in April 1945. He fled first to Austria, then to a Capuchin monastery in Altötting, Bavaria. In June 1945 he was captured by the Americans and extradited to the reconstituted Czechoslovakia to stand trial in October 1945.[30] On 15 April 1947, the Czechoslovak National Court (Národný súd) found him guilty of many (but not all) of the allegations against him, and sentenced him to death for "state treason, betrayal of the Slovak National Uprising and collaboration with Nazism". They concluded that Tiso's government had been responsible for the break-up of the Czechoslovak Republic and that "Tiso was an initiator, and, when not an initiator, then an inciter of the most radical solution of the Jewish question." Tiso appealed to the Czech President Edvard Beneš and expected a reprieve; his prosecutor had recommended clemency. However no reprieve was forthcoming.[31] Wearing his clerical outfit, Tiso was hanged (in an execution which was initially botched, so that he died slowly from suffocation, not instantly from a broken neck) in Bratislava on 18 April 1947. The Czechoslovak government buried him secretly to avoid having his grave become a shrine, although followers of Tiso mistakenly identified a recent grave as his and created a memorial there.[32]

Reputation

Under Communism, Tiso was formulaically denounced as a 'clerical Fascist'. With the fall of Communism in 1989, and the subsequent independence of Slovakia, heated debate began again on his role. James Mace Ward writes: "At its worst, [the debate] was fuel for an ultranationalist attempt to reconstruct Slovak society, helping to destabilize Czechoslovakia. At its best, the debate inspired a thoughtful reassessment of Tiso and encouraged Slovaks to grapple with the legacy of collaboration."[33]

See also

- Slovak Republic (1939–1945)

References

- Notes

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 21,

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 29-32.

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 21.

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 39.

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 42-54.

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 74.

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 80-4.

- ↑ For Tiso's early years, see Ward (2013) chapters 1-3.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 The Churches and the Deportation and Persecution of Jews in Slovakia; by Livia Rothkirchen; Vad Yashem.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Evans (2009) p.395

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 150-5. For Tiso's interwar political career, see also Felak (1995)

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 156-8

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 178-9.

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 179.

- ↑ Ian Kershaw; Hitler a Biography; 2008 Edn; W.W. Norton & Co; London; p. 476

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 181-2.

- ↑ Birnbaum, Eli (2006). "Jewish History 1940–1949". The History of the Jewish People. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ Bartl (2002) p. 142

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 211-213.

- ↑ Evans (2009) p.396

- ↑ See e.g. Ward (2013), pp. 271-280.

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 8 and pp. 234-7.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 "The Holocaust in Slovakia". Ushmm.org. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Mazower (2008) p. 394.

- ↑ Mazower (2008) p.395

- ↑ Friedländer, S. "Nazi Germany and The Jews 1933–1945". Harper Perennial, 2009. p. 306.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Mazower (2008) p.396

- ↑ Evans (2009) p. 396–397

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Evans (2009) p.397

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 258-9.

- ↑ Ward (2013) pp. 264-5.

- ↑ Ward (2013), p. 266.

- ↑ Ward (2013) p. 267.

- Bibliography

- Evans, Richard J. (2009). The Third Reich at War. New York: Penguin Press.

- Felak, James Ramon (1995). "At the Price of the Republic": Hlinka's Slovak People's Party, 1929–1938. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822937791.

- Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire - Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7139-9681-4.

- Ward, James Mace (2013). Priest, Politician, Collaborator: Jozef Tiso and the Making of Fascist Slovakia. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4988-8.

External links

- The Tiso plaque controversy

- Slovak Jews fear campaign to make fascism respectable

- Jozef Tiso - Slovak statehood at the bitter price of allegiance to Nazi Germany

| ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|