José María Valiente Soriano

| José María Valiente Soriano | |

|---|---|

| Born |

José María Valiente Soriano 1900 Chelva, Spain |

| Died |

1982 Valdecilla, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer, politician |

| Known for | Politician |

Political party | AP, CEDA, CT, UNE, DDE |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

José María Valiente Soriano (Chelva, 1900 - Valdecilla, 1982) was a Spanish Carlist politician.

Family and Youth

José María Valiente Soriano was born in the small Valencian town of Chelva to a petty bourgeoisie family; the son of José Valiente y Soriano and Micaela Soriano Alcaide, he had two sisters. His father was working as a notary; following his professional lot, the Valientes moved to Madrid during the last decades of the Restauración.

José María studied law first at the Universidad Central (later Universidad Complutense) in Madrid, to continue his juridical research with postgraduate doctoral thesis at the prestigious Università di Bologna (where he met Ramón Serrano Súñer, who was also studying jurisprudence). Valiente focused on the banking law and graduated cum laude in 1923. He commenced the career of a lawyer and an academic specialising in civil law at the faculty of law at the Universidad de Zaragoza, later to be also employed by the Universidad de Sevilla and the Universidad de la Laguna on the Canary Islands. Married to a Cantabrian aristocrat Consuelo Setién Rodríguez; the couple had three children.

Christian politician

In 1927 Valiente set up Juventud Católica de España, the ostensibly apolitical grouping concerned with defence and dissemination of Catholic values among the youth; in 1931 it was federated with Acción Católica, a broad organization of lay Catholics led by Ángel Herrera Oria. Later the same year, once the militantly secular course of the Republic began to take shape, he moved to politics by co-founding Acción Nacional (1932 to change its name to Acción Popular), a broad though heterogeneous conservative alliance, and became the vicepresident of its first National Committee. Since Acción Catolica banned its members from holding political party leadership roles Valiente had to resign from the JCE leadership.

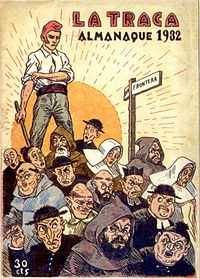

In 1933 Valiente proceeded to build the Acción Popular youth organisation, Juventudes de Acción Popular, and became its president. Soon afterwards AP transformed itself into Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas. JAP, now forming a juvenile branch of CEDA, retained its name and structure; Valiente continued to lead the organisation and became one of the national CEDA chieftains. Under his guidance Juventud became the aggressively anti-Lefist and pro-authoritarian group, though falling short of a typical "shirt organization" and denying similarity to Fascism. During the 1933 elections to the Cortes Valiente, thanks to his family Cantabrian links, negotiated a place on the local Unión de Derechas Agrarias list of candidates, and was comfortably elected from the Santander-Cantabria district.

Early 1934 Valiente at least twice secretly travelled to France to speak with Alfonso XIII. His aim was to negotiate the terms of modus vivendi between the monarchists and the accidentalist CEDA, and specifically to ask that for the time being the deposed king refrains from any statements that might impair CEDA's political fortunes. It is not exactly clear to what extent this mission was agreed with the party leader José Gil-Robles, since the two gave conflicting accounts of the incident, but it is usually accepted that the latter was at least approvingly aware. When the news of the Fontainebleau talks leaked to the press CEDA, the party which despite repeated declarations of loyalty towards the Republic was customarily accused of anti-Republican designs by the Left, found itself cornered and embarrassed. Eventually, the official version adopted by CEDA presented the incident as a monarchist plot within the organization. Valiente, apparently with his consent, was made a scapegoat and was expelled from the party. It is not unlikely that the militancy of JAP, perceived by the more acquiescent cedistas as compromising, might have contributed to the harsh line taken against Valiente. He had to leave JAP as well, replaced as its leader by José María Perez de Laborda.

Dissenting Carlist

Late 1935, amid a blaze of publicity, Valiente decided to join Comunión Tradicionalista. For the Carlists he was a valuable acquisition; the JAP militancy and the monarchist episode, embarrassing to the loyalist CEDA, were welcome credentials for the Traditionalists, who made little secret of their intention to do away with the godless regime as soon as possible. During the 1936 elections to the Cortes he ran on the Carlist ticket from the rather conservative Burgos constituency and was elected. His political standing on the national political scene was demonstrated when Valiente carried the coffin at the funeral of José Calvo Sotelo.

During the anti-Republican conspiracy Valiente's role was reduced to negotiations with the would-be Alfonsist allies in the Burgos province, where he resided during the coup of July 18. He became member of the Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra, where he took care of religious affairs. When Franco expulsed the Carlist leader Manuel Fal Conde from Spain, Valiente acted as his informal substitute. In 1937, facing the Franco's pressure to unite the Carlists and Falange, he shared neither the alacrity of Conde Rodezno nor the intransigence of Fal Conde. As one of 11 Carlists he entered the 50-member Consejo Nacional of the new organization (though not Junta Politica) and assumed the Burgos province jefatura, resigning his post in the Junta de Guerra. More than amalgamation within a motley grouping artificially created by the military he feared the breakup of Carlism into rodeznistas and falcondistas.

Having personal authorisation of the regent-claimant Don Javier Valiente remained in the Falangist Consejo Nacional (until 1942), but he refused the offer of Rodezno, who assumed the Ministry of Justice in the first Francoist cabinet of 1938 and asked Valiente to be his sub-secretary (the post went to Luis Arellano instead). Until 1942, when Franco ignored Don Javier's proposal of forming a Carlist-Francoist government, Valiente seemed to hope for a compromise, but he switched to opposition against Francoism later on. In 1945, following the Carlist anti-Francoist demonstrations in Pamplona, he was detained and expected facing the firing squad; eventually the sanctions adopted were relatively mild, especially compared to the terror employed against the Left.

As one of the key mid-age Carlist followers of Don Javier and his Jefe Delegado Fal Conde, Valiente was courted by Conde Rodezno. The latter invited him to join the juanistas, the group notionally loyal to the regency, but pressing the candidacy of Don Juan, the Alfonsist claimant, as the prospective Carlist king. Valiente refused to adhere; he ignored also the much smaller faction advocating the claim of Karl Pius Habsburg, styled as Carlos VIII and seemingly popular with some sections of the Falange. Valiente remained loyal to Don Javier - though less than enthusiastic - also in 1952, when the latter decided to end the regency and announced his own claim to the throne.

Collaborative Carlist

Around the mid-1950s the growing feeling among the javieristas was that the intransigent opposition, pursued by Manuel Fal Conde, produced few if any results. Don Javier seemed to agree. Following the resignation of Fal Conde, in 1955 he created Secretaría Nacional, a new collegial governing body of the movement, naming Valiente its president. Consistently opposing the plans of monarchical union, pursued by José María Arauz de Robles, Valiente engineered a more collaborative approach towards Francoism. The time seemed particularly opportune in 1957, when totalitarian plans of the Falangist leader José Arrese were rejected by Franco; the dictator started to make references to Traditionalism and to movimiento-comunión. The law on Principios Fundamentales del Movimiento, adopted in 1958, declared Spain to be Monarquía Tradicional.

The new strategy of posibilismo was welcomed with mixed feelings among the Carlists; older regional junteros grumbled and a young Navarrese, disguised as a priest, assaulted Valiente in a Pamplona street. His key ally against the internal opposition turned out to be the son of Don Javier, Carlos Hugo, who made a fulminant Príncipe de Asturias entry at the 1957 annual Carlist Montejurra amassment. The prince, greeted with exploding enthusiasm of the youth, delivered his La Proclama de Montejurra which, apart from social novelties, presaged modernization of the party and a more activist policy, which might have been interpreted as an offer to Franco. As Carlos Hugo moved permanently from France to Madrid, his cooperation with Valiente went well, resulting in Valiente's nomination to Jefe Delegado in 1960.

Initially the rapprochement, masterminded by Valiente and the leading hugocarlista Ramón Massó, looked promising. The socially radical Falangist leaders, José Solis and Raimundo Fernández-Cuesta, started to frequent Carlist meetings. Valiente had long audiences with Franco in 1961 and 1962, hearing from the dictator that he had not decided on his succession yet; Carlos Hugo was personally admitted to the Caudillo later. Franco allowed formation of Círculos Culturales Vázquez de Mella, semi-official Carlist offices, and authorized a few new Carlist periodicals. However, any other tangible results failed to materialize. The prince was ultimately denied the Spanish citizenship, no javierista Carlist landed any key position (though Valiente was rumored to take Ministry of Justice) and the regime failed to take a traditionalist turn.

Valiente, late 1950s dubbed "the strong man of Carlism", was gradually losing ground within the Comunión. In 1962 he had to share power with the new Secretaría Política, directed by Massó. In 1963 Zavala assumed presidency of Junta de Gobierno, a new executive Carlist body, leaving Valiente with still less powers of Jefe Delegado. Valiente was quoted saying there are many horses racing; we control neither the pace nor direction, but we have to run, an expression of his growing skepticism. Among the Carlists the frustration with the apparently unproductive collaborationist strategy was already rife. The policy crashed altogether when Valiente submitted his resignation in 1967 and Carlos Hugo was expulsed from Spain in 1968.

Traditionalist Carlist

In the mid-1960s the differences over posibilismo were becoming a function of an even more fundamental conflict. Valiente was alarmed when noticed that social radicalism of Carlos Hugo was losing its pro-Falangist tone and was taking an increasingly Marxist turn instead. The Basque question proved to be another field of discontent. In the late 1960s the young hugocarlistas already controlled the Carlist student organization AET, the trade-unionist MOT and the new militia GAC, and launched an open bid for control. The campaign, shrewdly engineered by Massó, accused the older leaders of over-committing to Francoism; the Civil-War Requeté leader José Luis Zamanillo was ousted and Valiente was left outmanoeuvred. Always loyal to Don Javier and usually enjoying his support in return, he was gradually estranged by the aging claimant, who accepted his resignation as Jefe Delegado in 1968. Despite his decline, Valiente maintained cordial relations with Don Javier. It changed when Valiente was designated to the Cortes as Franco's personal appointee. In what was an odd twist-and-turn of the failed collaborationist policy, the dictator decided to play Valiente against Carlos Hugo and to strengthen his position by making him a parliamentary deputy. Don Javier demanded that the nominee decline the assignment, but Valiente was already determined to confront the Left-bound hugocarlistas. In a personal letter to the claimant, dated November 1970, he underlined his loyalty to the Traditionalist principles, implicitly suggesting that it was Don Javier who might have abandoned them.

The open conflict lasted until 1971, but Valiente failed to gather enough support. At that time, the generation change within Carlism has already occurred. The Civil War leaders either died or due to their age were politically inactive; the Civil War rank-and-file were approaching retirement. The movement was gradually taken over by members who hardly remembered the Civil War and were raised in the Francoist Spain. With their support, during the series of Los Congresos del Pueblo Carlista, Carlos Hugo transformed the movement into Partido Carlista, adopted the titoist socialismo autogestionario platform and got Valiente expelled. When joined the next Cortes in 1971, Valiente was already representing himself only.

Juancarlista

In 1969 Franco formally designated Juan Carlos de Borbón as his successor. Valiente considered the young prince an acceptable future king, a leader loyal to the traditional conservative values and averse to liberal democratic ideas, apparently nurtured by his father, thought to be an opportunist. In 1972 he addressed the successor-in-waiting with a letter, suggesting it was a favorable moment to build a conservative monarchy departing from the Francoist model. Following relaxation of the law on political organizations, Valiente started working around a new broadly based monarchist party, possibly with titular presidency of Juan Carlos. The organization eventually materialized in 1975 as Unión Nacional Española, co-founded with Zamanillo, Antonio de Oriol and Miguel Fagoaga, though falling dramatically short of the original designs and missing the royal support.

Valiente welcomed the dismantling of Francoism, though not in the democratic direction eventually adopted during the transición. His new party, founded on the conservative, monarchist and Catholic basis, failed to gain popular support. UNE formed part of the broad right-of-the-centre Alianza Popular. In the 1977 elections AP arrived fourth with 8% of the votes, trailing far behind the Center and Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and losing slightly to the Communists. He abandoned the Alliance in 1978, refusing to endorse the 1978 constitution; at that time Valiente already nurtured no illusions about Juan Carlos as a king ensuring some sort of conservative, possibly Traditionalist continuity. In 1979 he joined Derecha Democrática Española, a renewed and failed attempt to build a popular conservative party; it was dissolved a year after Valiente's death, in 1982.

See also

References

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Julian Sanz Hoya, De la resistencia a la reacción: las derechas frente a la Segunda República, Salamanca 2006, ISBN 8481024201

- Sid Lowe, Catholicism, War and the Foundation of Francoism, Portland 2010, ISBN 9781845193737

- Jeremy Macclancy, The Decline of Carlism, Reno 2000, ISBN 9780874173444

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis], Valencia 2009

- Manuel Martorell Pérez, Retorno a la lealtad; el desafío carlista al franquismo, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788497391115

- José Luis Rodríguez Jiménez, Reaccionarios y golpistas. La extrema derecha en España: del tardofranquismo a la consolidación de la democracia (1967-1982), Salamanca 1994, ISBN 9788400074425

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, José María Valiente Soriano: Una semblanza política [in:] Memoria y Civilización 2012 (15), pp. 249–265, ISSN 11390107

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, Juanistas y carlistas: el intendio de unión monarquica de 1957, [in:] Aportes 57, XX, 1/2005, pp. 77–93

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del Carlismo hacia la colaboración con el regimen (1955-1956) [in:] Hispania LXIX / 231, pp. 179–208, ISSN 00182141

- Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El papel del carlismo navarro en el inicio de la fragmentación definitiva de la comunión tradicionalista (1957-1960), [in:] Principe de Viana 254, Pamplona 2011, ISSN 00328472

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, El carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo, Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788487863714

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, Los incidentes del 3 de diciembre de 1945 en la Plaza del Castillo, [in:] Principe de Viana 212, Pamplona 1997, pp. 629–650

- Aurora Villanueva Martinez, Organizacion, actividad y bases del carlismo navarro durante el primer franquismo [in:] Geronimo de Uztariz 19, pp. 97–117

External links

- political biography of Valiente

- Valiente in the "Gallery of Traitors" by a hugocarlista historian

- Sevilla University catalogue

- Bologna University catalogue

- JAP monography

- nobiliarios chronicle 1938

- Church and the Republic

- Catholicism and the Republic

- Carlism after 1937

- Carlism struggling to preserve identity under Francoism

- 1933 Cantabria elections

- Historical Index of Deputies

- Carlism after 1937

- Carlist Navarrese organisation during early Francoism

- Pamplona Dec 1945 incidents

- the collaborative turn of 1955-56

- Valiente and the Basque question

- Franco, Valiente and dynastical issues

- 1957-1960 breakup in Carlism

- political evolution 1968-1975 briefly discussed

- Dios y Patria propaganda (movie) on YouTube

- Carlos Hugo triumphant at Montejurra 1960s (movie) on YouTube

- Montejurra aplec pictures 1950-1970s

- Navarra during the transition

- they come, in numbers and weapons far greater than our own - Narnia version of the ultimate battle on YouTube

- Vizcainos! Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda on YouTube