Jolie Stahl

Jolie Stahl (born 1950) is a North American painter, sculptor, printer, and photographer. She has worked as a journalist and anthropologist and is also known for her active philanthropy in social work, humanitarian issues, and the applied arts.

Early career

Stahl spent her childhood in Los Angeles, California and later moved to New York where she attended the Dalton School. She then studied painting at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1968-1972); the Institute Allende in San Miguel, Mexico (1978); and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Skowhegan, Maine (1979). In 1979 she returned to New York and in 1982 joined COLAB (Collaborative Projects) a movement dedicated to furthering the critical social function of art in opposition to the galloping forces of commercialization and urban gentrification. She transferred her paintings and drawings to small “multiples” such as plastic shopping bags, gravestone-rubbing placemats, and jigsaw puzzles that became part of an exhibition entitled “The A. More Store.” The exhibit parodied the senseless commodification of the fine arts and appeared from 1982–84 at Barbara Gladstone Gallery, Artists Space, ABC No Rio, and the Jack Tilton Gallery, and Printed Matter in New York. This exhibition featured inexpensive works by some 150 artists, including then unknowns Tom Otterness, Kiki Smith, Jenny Holzer, and Barbara Kruger.[1]

Painting

Stahl’s early paintings were large oil portraits of her friends and fellow artists. Some canvases depicted bathers on Atlantic coast beaches. Other paintings attested to a fascination with books as objects that would recur in her Polaroid photography. The oils were exhibited in one-woman shows: “Artists Choose Artists” at Artists Space (New York), “Paintings in Praise of Joan Didion” at Atlantic Gallery (Boston) and “Seated Bathers” at Merrimack College (Massachusetts).

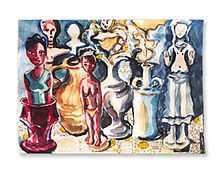

Beginning a period of extensive travel and journalistic work in 1985 Stahl took up aquarelle and collage as a more portable medium suitable for recording the variations of color and light in distant lands. While conducting ethnographic fieldwork in West Africa in 1991, she began collecting colons, vernacular wooden sculptures depicting African men and women in non-traditional jobs as seamstresses, dentists, attorneys, medical doctors, soldiers, filmmakers, race car drivers, and colonial administrators.[2] Originally, these tribal objects embodied a ritual negotiation of the political and social vicissitudes of early 20th century colonial life in French West Africa.[3] They symbolized the growing secularization of modernist development and a vested, yet ever ambiguous indigenous power versus the global cash economy.[4][5] Once discovered by foreign travelers the colons entered into circulation ironically as commodities for tourists seeking ‘authentic’ African souvenirs,[6] hence Stahl’s fascination at discovering an organized artistic dissidence evoking themes similar to those she explored in Colab’s “A. More Store.”

Her watercolors amplified these ironies by inviting the colons into the spaces and narratives of European Renaissance art. The startling juxtapositions were a trenchant commentary on global inequalities – virtual African tourists at the celebrated monuments of Western arts and culture, consuming their exploiters’ food and wine, appropriating their religious icons, meeting them face-to-face on the level playing field of artistic imagination. In exploring these themes Stahl resuscitated the moribund still-life painting style. She often embellished her paintings with collage and encaustic to secure a tactile bond among disparate compositional elements against background simulacra of Dutch wax print cottons, fusing modern & traditional motifs. Her extraordinarily dense works were the subject of a series of exhibitions from 1999-2006 including “Colon Watercolors” at the Museum for African Art, NY; “Mise en Place” at Lori Bookstein Gallery, NY; “Tuscan Travelogue and Other Watercolors” at the Palazzo Pretorio, San Donato, Italy; “The Genie’s Out of the Bottle” at Lori Bookstein Gallery, NY; “Bricolage” at the Convent of the Sacred Heart, Greenwich, CT; “Prima Luce” at Hudson Guild Gallery, NY; and “Watercolors” at Lori Bookstein Gallery, NY.

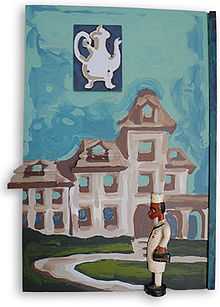

Responding to the Great Collapse of the housing market in 2008 Stahl began contemplating ideas of home in depictions of single-family houses and high-rise urban apartments. She created this new subject matter appropriately with latex house paints on wood scraps retrieved from housing construction sites. In several instances her colons reappear, visiting the Gilded Age mansions of Newport, Rhode Island as witnesses to the destructive havoc of overwrought economic speculation. This time, however, the African carvings are literally hewn and glued to the scene, presumably to add materiality to the ephemeral luxuries of the super-rich. These paintings debuted in a 2014 exhibition entitled “Home Economics” at the Hudson Guild Gallery part of New York’s oldest settlement house. The show also featured sculpture by Tom Otterness and photographs by Todd Hido.

Sculpture

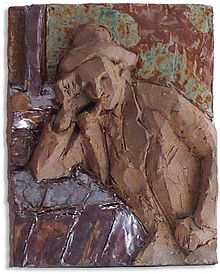

During the first decade of the 21st century Stahl carried her interests in narrative into the realm of terracotta reliefs where she revisits classical and modern depictions of Bible stories and myths. Sometimes using glazes or oil paint she reanimates the works of Cézanne, Chardin, Durer, Degas, Beckman, Balthus, Gaugin, Picasso, Piero della Francesca, Titian, and Mantegna. The collection recapitulates the narrative of Western art history while demonstrating a simultaneous command of mixed media in a burst of hues, colors, and fired textures. Examples appeared in 2011 alongside the reliefs of Natalie Charnoff, Jock Ireland, and Cynthia Harmon in “Relief: Drawing in Depth” at the Hudson Guild Gallery.

Prints and textiles

Her earliest silkscreen prints were part of a COLAB project and also printed original inserts for the East Village literary publication, Between C & D Magazine in 1984.[7] With Andrea Callard, a New York artist and filmmaker, she co-founded the Avocet Portfolio printmaking studio at Art Awareness in the Catskill Mountain town of Lexington, New York. With a grant from the New York State Council on the Arts, Avocet ran a two-year summer retreat (1985–86) where visiting artists, Becky Howland, Kiki Smith, and Richard Tobias contributed to a portfolio of fine art prints. Stahl’s own prints were made from rubbings of early American gravestones and featured many classical motifs. In addition to making paper silkscreen prints, she experimented with cotton textile productions, the results of which were presented to the annual meeting of the American Gravestone Society in early 1987. Later Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, an avant-garde Parisian designer purchased these textiles for his collection, commenting, “You Americans are so preoccupied with finality.” Stahl’s fascination with West African arts extended to textiles, principally the syncretic, profane, and whimsical motifs featured in wax print cottons. She turned examples from her collection into apparel and also incorporated them into her paintings.

Photography

Many of her early oil portraits were made from Polaroid SX-70 photos of her friends, fellow artists, and others. Some of these works were acquired by the permanent collection of the Polaroid Corporation. From that moment she became a devotee of this medium making abstract photos of books exhibited as “Books: The Physical Evidence” in 2012 at the Hudson Guild Gallery. Polaroid went bankrupt in 2001 and stopped producing its instant film in 2009, yet Stahl continues to experiment with the medium using SX-70 compatible film manufactured by The Impossible Project.

Stahl began work as a documentary photographer in 1985 using 35-mm black & white and color film in SLR and Rangefinder cameras. She worked as freelance photojournalist covering the armed resistance to the covert American military operations in Nicaragua and El Salvador, and the U.S.-backed fascist contras in Honduras; the popular rebellion against the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines; the Moro National Liberation Front separatist movement in Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago;[8] and squatter settlements in the cemeteries of Manila.[9] The stories were also published in NACLA Report on the Americas and Hijrah Magazine. From 1988 to 1993 as a contributing photographer to The City Sun, a Brooklyn weekly newspaper, she shot numerous features of cultural and social significance.[10] Her photograph of “Dr." Rasheed Abdullah Rasheed taken in 1988 became a breaking news story when he was identified as an American co-conspirator in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.[11]

From 1996 to 2000 she was the curator of photography at the Elsa Mott Ives Gallery in New York where her work was featured in “Family Ties,” “The Sporting Life,” and “Infinite Possibilities.” In 1997 her work appeared in the “Festival of Women Photographers” at the New York Public Library that gave rise to the exhibition’s groundbreaking catalogue.[12]

Visual ethnography

Stahl is the co-author with her husband Robert Dannin of Black Pilgrimage to Islam, the result of independently financed research about the propagation of normative Islam in the US and Canada.[13] This undertaking was the first successful and comprehensive ethnographic study about the propagation of orthodox Islam among black Americans, a phenomenon originating in early 20th century. From 1988-94 she performed fieldwork among American Muslim women and documented the entire project photographically. Some of this unprecedented research took place in maximum-security penitentiaries in New York, California and Ohio where they studied the development of Muslim prison subcultures.[14] Questions concerning cross-cultural relations in the Islamic world also led her to Senegal to study the participation of young black Americans in the Tijaniyyah, one of West Africa's transnational Sufi brotherhoods. Black Pilgrimage to Islam and other scholarly publications featured her photographs and received enthusiastic reviews in The Times Literary Supplement,[15] The Washington Post,[16] The Chronicle of Higher Education,[17] and Le Monde Diplomatique.[18] Her photographic documentation was acquired in 2013 by the New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Philanthropy

Jolie Stahl is the founding director and president of the Ddora Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving American arts and handicrafts. The foundation supports teachers and students of such traditional crafts as woodworking, blacksmithing, basket making, boat building, decorative arts, and historic preservation. From 1998-2012 she served on the Board of Directors of the International Medical Corps, an NGO that sends physicians and medical supplies to assist the civilian victims of natural disasters and political upheavals. She was the founder and chief fundraiser for the Next Generation Teen Center run by New York’s Children's Aid Society as an afterschool home and counseling forum for high school students in the South Bronx.

References

- ↑ Alan W. Moore and Marc Miller, eds., ABC No Rio Dinero: The Story of a Lower East Side Art Gallery, (Collaborative Projects (Colab), NY, 1985).

- ↑ Eliane Girard and Brigitte Kernel, Colons, Statuettes Habillées D’Afrique De L’Ouest, (Paris: Syros Alternatives, 1993).

- ↑ Fritz Kramer, The Red Fez, Art and Spirit Possession in Africa, (New York: Verso, 1993).

- ↑ Philip Ravenhill, Dreams and Reveries, Images of Other World Mates Among the Baule, West Africa, (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996).

- ↑ Robert Farris Thompson, Flash of the Spirit, (New York: Vintage, 1984).

- ↑ Christopher B. Steiner, African Art in Transit, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.)

- ↑ Joel Rose, Between C & D: New Writing from the Lower East Side Fiction Magazine, (New York: Penguin, 1987).

- ↑ “Bangsa Moro! Muslim Insurgency in the Philippines" Il Venerdi di Repubblica, 15 May 1988

- ↑ ”The Manila Cemetery Provides a Home for Living and Dead” and “The Chinese Cemetery in Manila”, American Cemetery Magazine, 1986.

- ↑ The 'Holy War' on Crack," The City Sun, (23 August 1988); "Masjid Sankore," The City Sun, (22 November 1989); "Still Angry - After All These Years," The City Sun, (13 February 1990).

- ↑ Francis X. Clines, “U.S. Suspect in Bombing Plots – Zealous Causes and Civic Roles,” New York Times, 28 June 1993.

- ↑ Naomi Rosenblum, A History of Women Photographers, (Abbeville Press, 1994).

- ↑ Robert Dannin & Jolie Stahl, Black Pilgrimage to Islam, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- ↑ ”Faith Behind Bars” Newsday Magazine, 4 June 1989.

- ↑ Malise Ruthven, "The Muslim's Cell," The Times Literary Supplement, 28 February 2003, page 28.

- ↑ Sonsyrea Tate,"The Call of the Prophet,"Washington Post, 3 March 2002; page BW09.

- ↑ Peter Monaghan,"Rescuing a History from Obscurity", The Chronicle of Higher Education,19 April 2002, page A18.

- ↑ “Ces musulmans courtisés et divisés," Le Monde Diplomatique, (February 1993).