John Willie

| John Willie | |

|---|---|

| Born |

John Alexander Scott Coutts 9 December 1902 Singapore |

| Died |

5 August 1962 (aged 59) England |

| Occupation | Photographer, artist, comic strip cartoonist, Editor of Bizarre Magazine (1946-1956) |

John Alexander Scott Coutts (9 December 1902 – 5 August 1962), better known by the pseudonym John Willie, was the artist, fetish photographer, editor, and publisher of the soft-porn cult magazine Bizarre. Willie is best known for his bondage comic strips, specifically "Sweet Gwendoline", featuring the villain Sir Dystic d'Arcy. Coutts was able to avoid controversy in censorship through careful attention to guidelines and the use of humor. Though "Bizarre" was a small format magazine, it had a huge impact on later kink publications and experienced a resurgence in popularity along with well-known fetish model, Bettie Page, in the 1980s.

Early life

John Coutts was born in 1902 to a British family in Singapore, but moved with his family to England in 1903, where he grew up during the Edwardian era. It has been suggested that the restrictive fashions worn by women of that time, such as whale-bone corsets, and the constant repression of sex and sexual desire characteristic of this era, may "go some distance to explain [Willie’s] fluency in the semiotics of dress." [1] He is said to have had a rather typical upbringing in a middle-class family and attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Although he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant into the Royal Scots, Coutts was forced to resign in 1925 when he married a night-club hostess, Eveline Fisher, without the permission of his commanding officer. He migrated with his wife to Australia, where their marriage ended in divorce in 1930.[2]

Early career

After moving to Brisbane, Australia, in 1926, Coutts was able to put his affinity for fetish wear to use when he joined the High Heel Club, where he was probably introduced to the print media of a community of "shoe lovers" and other fetishists.[3] He met his future second wife, Holly Anna Faram, sometime in the early 1930s, and the couple married in 1942.[4] She became his muse and modelled for him often. When one compares Willie’s drawings and photographs of his wife, one is left with the impression that Faram incorporated his ideal body type, tall and slender, and she is said to have shared the artist’s interest in bondage and high heels.[1] Because of his access to the High Heel Club’s mailing list, Willie was able to begin producing and selling his own illustrations and photography. He worked at a variety of jobs as well as pursuing his hobby and eventually established a company to produce exotic footwear, called "Achilles". In 1945, Willie moved to North America, while Holly chose to remain in Australia, where she died in 1983 at the age of 70. Willie hoped to settle in New York but was forced to remain in Montreal, Canada, for a year or so because of immigration issues.[3]

John Willie's Work and Bizarre

Bizarre magazine began in 1946, while Coutts was living in Canada.[1] He published the magazine under the phallic pseudonym of "John Willie" a name he kept for the duration of his career as publisher of the magazine. Willie also worked with Irving Klaw, the infamous BDSM photographer who was tried in New York for obscenity in 1955, and many other girlie magazines, but he is best known for his character Sweet Gwendoline, which he drew in a clear, anatomically correct style that influenced later artists such as ENEG and Eric Stanton. Other characters include U69 (censored to U89 in some editions), the raven-haired dominatrix who ties up Gwendoline, and Sir Dystic d'Arcy, the only prominent male character and probably a parody of Willie himself.[5] Sweet Gwendoline was published as a serial in Robert Harrison's mainstream girlie magazine Wink from June 1947 to February 1950.

Bizarre was published, at somewhat irregular intervals, from 1946 to 1959 (compare with ENEG's work in Exotique magazine, published 1956-59). The magazine included many photographs, often of Willie's wife, and drawings of costume designs, some based on ideas from readers. There were also many letters from readers; he was accused of inventing these but insisted that they were genuine. The letters covered interests such as high heels, bondage, amputee fetishism, sadomasochism, transvestism, corsets, and body modification. "Bizarre" is known for its gender-bending nature and included editorials from men such as R. W., who wrote in issue no. 13: "Dear Sir:... Since my wife has been reading Bizarre she has realized my interests are not so strange and that others do likewise. Thanks to you Mr. Editor I can now dress as I please on occasion. As a corset lover this means high heels and real original wasp waisted corsets laced to give a five or six inch reduction in waist measure. I have been collecting these for some time."[6]

Willie was very careful always to portray gender-bending and male-to-female as well as female-male transvestitism as heteronormative, ignoring the idea that many suggested which was the link from homosexuality to subverting gender norms. This also allows Willie to be credited with transgressing against the traditional understanding of the male gaze, where man looks upon woman and woman acts as an object upon which to be gazed. Although the figures in the magazine were most often female-bodied, it is never clear that the intended audience is male. In fact, because of the "bizarre" nature of the magazine, the intended audience was understood as female, male, intersex, or any in-between. Further subverting the idea that the magazine was produced specifically for men is the fact that in every single image of bondage where a woman is being tied up, it is another woman who is doing the tying. According to Julia Pine, this could allude to lesbian play and was "intended for the titillation of both male and female."[1] Coutts was very attentive to satisfying all readers of his work and often wrote editorials on the subject.

The magazine was suspended completely from 1947 to 1951 because of paper shortages and other lasting effects of the Second World War. By 1956 Coutts was ready to give up the magazine, and that year he sold it to someone described only as R.E.B., who published six more issues before "Bizarre" finally folded in 1959. There was no mention within the magazine that it had changed hands, but in issue 23 Mahlon Blaine was introduced by the editor as the artist who was to replace Willie as the primary illustrator.[7]

After publishing the first 23 issues of Bizarre, Coutts moved to Hollywood, California, where in 1961 he developed a brain tumor and was forced to stop his mail-order business. He destroyed his archives and returned home to England, where he died in his sleep in August 1962.

Willie was portrayed by Jared Harris in the movie The Notorious Bettie Page (2006), which featured a fictional meeting between Willie and Page.

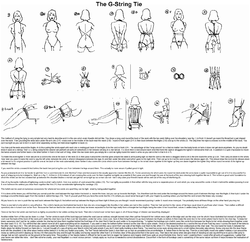

G-string tie

The g-string tie method of bondage was popularised by John Willie. He regarded it as exceptionally difficult to escape from, claiming that even Harry Houdini did not like trying to escape from it. His published description is available online.

Controversy and censorship

Despite the pornographic nature of the magazine, Coutts was able to circumvent censorship and orders to cease publication because he was careful to avoid "nudity, homosexuality, overt violence, or obvious depictions of things that might be read as perverse or immoral and that might rankle those parties who were capable of banning, censoring, or blocking circulation."[1]

Quotations

"Unless a model is a good actress, and has 'that type' of face, it's difficult for her to look sad and miserable when working for me. My studio is a pretty cheerful place, and quite unlike the atmosphere that surrounds Gwendoline when the Countess gets hold of her." [8]

"Bizarre. The magazine for pleasant optimists who frown on convention. The magazine of fashions and fantasies fantastic! Innumerable journals deal with ideas for the majority. Must all sheeplike follow in their wake? Bizarre is for those who have the courage of their own convictions. Conservative? —Old fashioned? —Not by any means! Where does a complete circle begin or end? And doesn't fashion move in a circle? Futuristic? Not even that—there is nothing new in fashion, it is only for the application of new materials—new ornaments—a new process of making—coupled with the taste and ability to create the unusual and unorthodox to the trend of the moment."[9]

“As for sex, ignorance is abysmal, because for centuries those who could not satisfy themselves, except by denying pleasure to others, have taught generation after generation that "sex is taboo." Thou shalt not think about it or discuss it. In fact, it's a dreadful thing, but it's all right as long as you don't enjoy it. If you have any other ideas on the subject, you are a pervert. The basis of a decent society is a happy home. Marriages break up almost invariably because of sex. What you do, or do not do, is your own business, all that matters is that the enjoyment be mutual,—and the time to discuss these things is before you get hitched up. There is a partner to suit everyone somewhere, but the search will be difficult until we can discuss our likes and dislikes, openly, in good taste, without threat from our own brand of standardized Police State.”[10]

See also

- Fetish artist

- Eric Stanton

- Irving Klaw

- Sexual fetishism

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 http://utexas.metapress.com/content/r05x577r3n1g7r50/

- ↑ Investigatpr.records.nsw.gov.au

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Rund, The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline, pp. v-viii.

- ↑ Bdm.nsw.gov.au

- ↑ Glenn Daniel Wilson, Variant sexuality: research and theory, Taylor & Francis, 1987, ISBN 0-7099-3698-2, p.15

- ↑ R. W., Bizarre, no. 13 (1954): 57

- ↑ R.E.B., Bizarre no. 23 (1958): 8

- ↑ John Willie, The Art of John Willie, Sophisticated Bondage - Book Two, p. 1

- ↑ Coutts, Bizarre, no. 3 (1946): 2

- ↑ Coutts, Bizarre no. 17 (1956): 5

Further reading

- A John Willie Portfolio, n. 1 (a cura di Carl McGuire), Van Nuys, CA., London Ent. Ltd., 1987

- Bizarre: The Complete Reprint of John Willie's Bizarre, Vols. 1-26; ISBN 3-8228-9269-6 Taschen. Edited by Eric Kroll.

- Plusieurs possibilités. Photographies de John Willie, Paris, Futuropolis, 1985

- The Art of John Willie - Sophisticated Bondage (Book One)

- An illustrated biography edited by Stefano Piselli & Riccardo Morrocchi (128 pages)

- The Art of John Willie - Sophisticated Bondage (Book Two)

- An illustrated biography edited by Stefano Piselli & Riccardo Morrocchi (128 pages)

- The Bound Beauties of Irving Klaw & John Willie, vol 2, Van Nuys, CA., Harmony Comm., 1977

- The First John Willie Bondage Photo Book, Van Nuys, CA., London Ent. Ltd., 1978

- The Second John Willie Bondage Photo Book, Van Nuys, CA., London Ent. Ltd., 1978

- The Works of John Willie (a cura di Peter Stevenson), s.l., s.e., s.d.*

- The Adventures of Sweet Gwendoline (Second Edition, Revised & Enlarged) New York: Bélier Press, 1999. 368 pp. ISBN 0-914646-48-6

External links

- Lambiek.net

- "The Rembrandt of Pulp"

- Belierpress.com

- American Fetish - Scholarly resources for the study of SM and Fetishism in American Culture