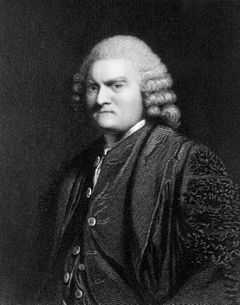

John Pringle

| Sir John Pringle, Bt | |

|---|---|

|

John Pringle | |

| Born |

10 April 1707 Stitchel, Roxburgh, Scotland[1] |

| Died |

18 January 1782 London, England[2] |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Fields | physician |

| Alma mater | University of St Andrews |

| Known for | antiseptics |

| Notable awards | Copley Medal (1752) |

Sir John Pringle, 1st Baronet, PRS (10 April 1707 – 18 January 1782) was a Scottish physician who has been called the "father of military medicine" (although Ambroise Paré and Jonathan Letterman have also been accorded this sobriquet).

Biography

Youth and early career

John Pringle was the youngest son of Sir John Pringle, 2nd Baronet, of Stichill, Roxburghshire (1662–1721), by his spouse Magdalen (d. December 1739), daughter of Sir Gilbert Elliot, of Stobs.

He was educated at St Andrews, at Edinburgh, and at Leiden. In 1730 he graduated with a degree of Doctor of Physic at the last-named university, where he was an intimate friend of Gerard van Swieten and Albrecht von Haller.

He settled in Edinburgh at first as a physician, but between 1733 and 1744 was also Professor of Moral Philosophy at Edinburgh University.

In 1742 he became physician to the Earl of Stair, then commanding the British army in Flanders. About the time of the battle of Dettingen in Bavaria in June 1743, when the British army was encamped at Aschaffenburg, Pringle, through the Earl of Stair, brought about an agreement with the Duc de Noailles, the French commander, that military hospitals on both sides be considered as neutral, immune sanctuaries for the sick and wounded, and should be mutually protected. The International Red Cross, as constituted by the modern Geneva Conventions, developed from this conception and agreement.[3]

In 1744 he was appointed by the Duke of Cumberland physician-general to the forces in the Low Countries. In 1749, having settled in a smart house in Pall Mall, London, he was made physician in ordinary to the Duke of Cumberland.

On 1 April 1752 he married Charlotte (d. Dec 1753) second daughter of Dr William Oliver (1695–1764) of Bath, the inventor of Bath Oliver biscuits, but they had no issue.

On 5 June 1766 John Pringle was created a baronet, and in 1774 he was appointed Physician to His Majesty King George III.

He was also a frequent travel companion to Benjamin Franklin.

Academia

His first book, Observations on the Nature and Cure of Hospital and Jayl Fevers, was published in 1750, and in the same year he contributed to the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society three papers on Experiments on Septic and Antiseptic Substances, which gained him the Copley Medal. Two years later he published his important work, Observations on the Diseases of the Army in Camp and Garrison, which entitles him to be regarded as the founder of modern military medicine.

In November 1772 he was elected president of the Royal Society, a position he held until 1778. In this capacity he delivered six discourses, which were afterwards collected into a single volume (1783).

Pringle was a regular correspondent and friend of James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, the Scottish philosopher. Monboddo was an important thinker in pre-evolutionary theory, and some scholars actually credit him with the concept of evolution; however, Monboddo was also quite eccentric, which was one reason for Monboddo's not receiving credit for the evolution concepts. It was in a letter to Pringle in 1773 that Monboddo revealed he did not really hold to a belief of men being born with tails, which was the chief point of his ridicule.[4]

After passing his seventieth year he went, briefly, to Edinburgh in 1780, but returned to London in September 1781, and died in the following year.

Legacy

There is a monument to Pringle in Westminster Abbey, executed by Nollekens. At Sir John's death his baronetcy became extinct.

After a legal case in 2004, the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh was able to open the Pringle papers it holds to the public.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/476980/Sir-John-Pringle-1st-Baronet

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/476980/Sir-John-Pringle-1st-Baronet

- ↑ The Evolution of Preventive Medicine in the United States Army 1607–1939: The Colonial Period (1607–1775)

- ↑ Letter from Lord Monboddo to Sir John Pringle, 16 June 1773; reprinted by William Knight 1900 ISBN 1-85506-207-0

- ↑ http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/scotland/4007407.stm

- Selwyn, S (1966), "Sir John Pringle: hospital reformer, moral philosopher and pioneer of antiseptics", Medical history (July 1966) 10 (3): 266–74, doi:10.1017/s0025727300011133, PMC 1033606, PMID 5330009

- Hamilton, D (1965), "Sir John Pringle (1707–1782), Military Physician and Hygienist", Revue international des services de santé des armées de terre, de mer et de l'air (June 1965) 38: 497–8, PMID 14348441

- "Sir John Pringle (1707–1782), Military Physician and Hygienist", JAMA (Nov 30, 1964) 190, 1964: 849–50, doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03070220055019, PMID 14205667

- Hamilton, D (1964), "Sir John Pringle", Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps 110: 138–47, PMID 14189958

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1896). "Pringle, John". Dictionary of National Biography 46. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 386–8.

Lee, Sidney, ed. (1896). "Pringle, John". Dictionary of National Biography 46. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 386–8. - Extinct and Dormant Baronetcies of England, Ireland, and Scotland, by Messrs. John and John Bernard Burke, 2nd edition, London, 1841, p. 428.

- Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage, edited by Peter Townend, London, 1970, 105th edition, p. 2186.

- ClanPringle.org.uk

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pringle, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Pringle, Sir John". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| Preceded by New creation |

Baronet (of Pall Mall) 1766–1782 |

Succeeded by Extinct |

| ||||||||||

|