John Milton

| John Milton | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Milton c. 1629, National Portrait Gallery, London. Unknown artist (detail) | |

| Born |

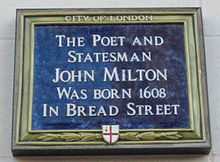

9 December 1608 Bread Street, Cheapside, London, England |

| Died |

8 November 1674 (aged 65) Bunhill, London, England |

| Resting place | St Giles-without-Cripplegate |

| Occupation | Poet, prose polemicist, civil servant |

| Language | English, Latin, French, German, Greek, Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, Aramaic, Syriac |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Christ's College, Cambridge |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell. He wrote at a time of religious flux and political upheaval, and is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost (1667), written in blank verse.

Milton's poetry and prose reflect deep personal convictions, a passion for freedom and self-determination, and the urgent issues and political turbulence of his day. Writing in English, Latin, Greek, and Italian, he achieved international renown within his lifetime, and his celebrated Areopagitica (1644)—written in condemnation of pre-publication censorship—is among history's most influential and impassioned defences of free speech and freedom of the press.

William Hayley's 1796 biography called him the "greatest English author,"[1] and he remains generally regarded "as one of the preeminent writers in the English language,"[2] though critical reception has oscillated in the centuries since his death (often on account of his republicanism). Samuel Johnson praised Paradise Lost as "a poem which...with respect to design may claim the first place, and with respect to performance, the second, among the productions of the human mind," though he (a Tory and recipient of royal patronage) described Milton's politics as those of an "acrimonious and surly republican".[3]

Biography

The phases of Milton's life parallel the major historical and political divisions in Stuart Britain. Under the increasingly personal rule of Charles I and its breakdown in constitutional confusion and war, Milton studied, travelled, wrote poetry mostly for private circulation, and launched a career as pamphleteer and publicist. Under the Commonwealth of England, from being thought dangerously radical and even heretical, the shift in accepted attitudes in government placed him in public office, and he even acted as an official spokesman in certain of his publications. The Restoration of 1660 deprived Milton, now completely blind, of his public platform, but this period saw him complete most of his major works of poetry.

Milton's views developed from his very extensive reading, as well as travel and experience, from his student days of the 1620s to the English Revolution.[4] By the time of his death in 1674, Milton was impoverished and on the margins of English intellectual life, yet famous throughout Europe and unrepentant for his political choices.

Early life

John Milton was born in Bread Street, London, on 9 December 1608, the son of the composer John Milton and his wife, Sarah Jeffrey. The senior John Milton (1562–1647) moved to London around 1583 after being disinherited by his devout Catholic father, Richard Milton, for embracing Protestantism. In London, the senior John Milton married Sarah Jeffrey (1572–1637) and found lasting financial success as a scrivener.[5] He lived in, and worked from, a house on Bread Street, where the Mermaid Tavern was located in Cheapside. The elder Milton was noted for his skill as a musical composer, and this talent left his son with a lifelong appreciation for music and friendships with musicians such as Henry Lawes.[6]

Milton's father's prosperity provided his eldest son with a private tutor, Thomas Young, a Scottish Presbyterian with an M.A. from the University of St. Andrews. Research suggests that Young's influence served as the poet's introduction to religious radicalism.[7] After Young's tutorship Milton attended St Paul's School in London. There he began the study of Latin and Greek, and the classical languages left an imprint on his poetry in English (he also wrote in Italian and Latin).

Milton's first datable compositions are two psalms done at age 15 at Long Bennington. One contemporary source is the Brief Lives of John Aubrey, an uneven compilation including first-hand reports. In the work, Aubrey quotes Christopher, Milton's younger brother: "When he was young, he studied very hard and sat up very late, commonly till twelve or one o'clock at night".[8]

In 1625 Milton began attending Christ's College, Cambridge. He graduated with a B.A. in 1629,[9] and ranked fourth of 24 honours graduates that year in the University of Cambridge.[10] Preparing to become an Anglican priest, Milton stayed on to obtain his Master of Arts degree on 3 July 1632.

Milton was probably rusticated (suspended) for quarrelling in his first year with his tutor, Bishop William Chappell. He was certainly at home in the Lent Term 1626; there he wrote his Elegia Prima, a first Latin elegy, to Charles Diodati, a friend from St Paul's. Based on remarks of John Aubrey, Chappell "whipt" Milton.[8] This story is now disputed, though certainly Milton disliked Chappell.[11] Historian Christopher Hill cautiously notes that Milton was "apparently" rusticated, and that the differences between Chappell and Milton may have been either religious or personal.[12] It is also possible that, like Isaac Newton four decades later, Milton was sent home because of the plague, by which Cambridge was badly affected in 1625. Later, in 1626, Milton's tutor was Nathaniel Tovey.

At Cambridge, Milton was on good terms with Edward King, for whom he later wrote Lycidas. He also befriended Anglo-American dissident and theologian Roger Williams. Milton tutored Williams in Hebrew in exchange for lessons in Dutch.[13] At Cambridge Milton developed a reputation for poetic skill and general erudition, but experienced alienation from his peers and university life as a whole. Watching his fellow students attempting comedy upon the college stage, he later observed 'they thought themselves gallant men, and I thought them fools'.[14]

Milton was disdainful of the university curriculum, which consisted of stilted formal debates on abstruse topics, conducted in Latin. His own corpus is not devoid of humour, notably his sixth prolusion and his epitaphs on the death of Thomas Hobson. While at Cambridge he wrote a number of his well-known shorter English poems, among them On the Morning of Christ's Nativity, his Epitaph on the admirable Dramatick Poet, W. Shakespeare, his first poem to appear in print, L'Allegro and Il Penseroso.

Study, poetry, and travel

It appears in all his writings that he had the usual concomitant of great abilities, a lofty and steady confidence in himself, perhaps not without some contempt of others; for scarcely any man ever wrote so much, and praised so few. Of his praise he was very frugal; as he set its value high, and considered his mention of a name as a security against the waste of time, and a certain preservative from oblivion.[15]

Upon receiving his M.A. in 1632, Milton retired to Hammersmith, his father's new home since the previous year. He also lived at Horton, Berkshire, from 1635 and undertook six years of self-directed private study. Christopher Hill argues that this was not retreat into a rural idyll: Hammersmith was then a "suburban village" falling into the orbit of London, and even Horton was becoming deforested, and suffered from the plague.[16] He read both ancient and modern works of theology, philosophy, history, politics, literature and science, in preparation for a prospective poetical career. Milton's intellectual development can be charted via entries in his commonplace book (like a scrapbook), now in the British Library. As a result of such intensive study, Milton is considered to be among the most learned of all English poets. In addition to his years of private study, Milton had command of Latin, Greek, Hebrew, French, Spanish, and Italian from his school and undergraduate days; he also added Old English to his linguistic repertoire in the 1650s while researching his History of Britain, and probably acquired proficiency in Dutch soon after.[17]

Milton continued to write poetry during this period of study: his Arcades and Comus were both commissioned for masques composed for noble patrons, connections of the Egerton family, and performed in 1632 and 1634 respectively. Comus argues for the virtuousness of temperance and chastity.

He contributed his pastoral elegy Lycidas to a memorial collection for one of his Cambridge classmates. Drafts of these poems are preserved in Milton’s poetry notebook, known as the Trinity Manuscript because it is now kept at Trinity College, Cambridge.

In May 1638, Milton embarked upon a tour of France and Italy that lasted up to July or August 1639.[18] His travels supplemented his study with new and direct experience of artistic and religious traditions, especially Roman Catholicism. He met famous theorists and intellectuals of the time, and was able to display his poetic skills. For specific details of what happened within Milton's "grand tour", there appears to be just one primary source: Milton's own Defensio Secunda. Although there are other records, including some letters and some references in his other prose tracts, the bulk of the information about the tour comes from a work that, according to Barbara Lewalski, "was not intended as autobiography but as rhetoric, designed to emphasise his sterling reputation with the learned of Europe."[19]

In [Florence], which I have always admired above all others because of the elegance, not just of its tongue, but also of its wit, I lingered for about two months. There I at once became the friend of many gentlemen eminent in rank and learning, whose private academies I frequented—a Florentine institution which deserves great praise not only for promoting humane studies but also for encouraging friendly intercourse.[20]

He first went to Calais, and then on to Paris, riding horseback, with a letter from diplomat Henry Wotton to ambassador John Scudamore. Through Scudamore, Milton met Hugo Grotius, a Dutch law philosopher, playwright and poet. Milton left France soon after this meeting. He travelled south, from Nice to Genoa, and then to Livorno and Pisa. He reached Florence in July 1638. While there, Milton enjoyed many of the sites and structures of the city. His candour of manner and erudite neo-Latin poetry earned him friends in Florentine intellectual circles, and he met the astronomer Galileo, who was under house arrest at Arcetri, as well as others.[21] Milton probably visited the Florentine Academy and the Academia della Crusca along with smaller academies in the area including the Apatisti and the Svogliati.

He left Florence in September to continue to Rome. With the connections from Florence, Milton was able to have easy access to Rome's intellectual society. His poetic abilities impressed those like Giovanni Salzilli, who praised Milton within an epigram. In late October, Milton, despite his dislike for the Society of Jesus, attended a dinner given by the English College, Rome, meeting English Catholics who were also guests, theologian Henry Holden and the poet Patrick Cary.[22] He also attended musical events, including oratorios, operas and melodramas. Milton left for Naples toward the end of November, where he stayed only for a month because of the Spanish control.[23] During that time he was introduced to Giovanni Battista Manso, patron to both Torquato Tasso and to Giovanni Battista Marino.[24]

Originally Milton wanted to leave Naples in order to travel to Sicily, and then on to Greece, but he returned to England during the summer of 1639 because of what he claimed, in Defensio Secunda,[25] were "sad tidings of civil war in England."[26] Matters became more complicated when Milton received word that Diodati, his childhood friend, had died. Milton in fact stayed another seven months on the continent, and spent time at Geneva with Diodati's uncle after he returned to Rome. In Defensio Secunda, Milton proclaimed he was warned against a return to Rome because of his frankness about religion, but he stayed in the city for two months and was able to experience Carnival and meet Lukas Holste, a Vatican librarian, who guided Milton through its collection. He was introduced to Cardinal Francesco Barberini who invited Milton to an opera hosted by the Cardinal. Around March Milton travelled once again to Florence, staying there for two months, attending further meetings of the academies, and spent time with friends. After leaving Florence he travelled through Lucca, Bologna, and Ferrara before coming to Venice. In Venice, Milton was exposed to a model of Republicanism, later important in his political writings, but he soon found another model when he travelled to Geneva. From Switzerland, Milton travelled to Paris and then to Calais before finally arriving back in England in either July or August 1639.[27]

Civil war, prose tracts, and marriage

On returning to England, where the Bishops' Wars presaged further armed conflict, Milton began to write prose tracts against episcopacy, in the service of the Puritan and Parliamentary cause. Milton's first foray into polemics was Of Reformation touching Church Discipline in England (1641), followed by Of Prelatical Episcopacy, the two defences of Smectymnuus (a group of Presbyterian divines named from their initials: the "TY" belonged to Milton's old tutor Thomas Young), and The Reason of Church-Government Urged against Prelaty. With frequent passages of real eloquence lighting up the rough controversial style of the period, and deploying a wide knowledge of church history, he vigorously attacked the High-church party of the Church of England and their leader, William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury.

Though supported by his father's investments, at this time Milton became a private schoolmaster, educating his nephews and other children of the well-to-do. This experience, and discussions with educational reformer Samuel Hartlib, led him to write in 1644 his short tract, Of Education, urging a reform of the national universities.

In June 1642, Milton paid a visit to the manor house at Forest Hill, Oxfordshire, and returned with a 16-year-old bride, Mary Powell.[28][29] A month later, finding life difficult with the severe 35-year-old schoolmaster and pamphleteer, Mary returned to her family. Partly because of the outbreak of the Civil War,[28] she did not return until 1645; in the meantime her desertion prompted Milton, over the next three years, to publish a series of pamphlets arguing for the legality and morality of divorce. (Anna Beer, one of Milton's most recent biographers, points to a lack of evidence and the dangers of cynicism in urging that it was not necessarily the case that the private life so animated the public polemicising.) In 1643, Milton had a brush with the authorities over these writings, in parallel with Hezekiah Woodward, who had more trouble.[30] It was the hostile response accorded the divorce tracts that spurred Milton to write Areopagitica, his celebrated attack on pre-printing censorship. In Areopagitica, Milton not only aligns himself with the parliamentary cause, he also begins to synthesize the ideal of neo- Roman liberty with that of Christian liberty.[31][32]

Secretary for Foreign Tongues

With the parliamentary victory in the Civil War, Milton used his pen in defence of the republican principles represented by the Commonwealth. The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1649) defended popular government and implicitly sanctioned the regicide; Milton's political reputation got him appointed Secretary for Foreign Tongues by the Council of State in March 1649. Though Milton's main job description was to compose the English Republic's foreign correspondence in Latin, he also was called upon to produce propaganda for the regime and to serve as a censor.[33] In October 1649, he published Eikonoklastes, an explicit defence of the regicide, in response to the Eikon Basilike, a phenomenal best-seller popularly attributed to Charles I that portrayed the King as an innocent Christian martyr. A month after Milton had tried to break this powerful image of Charles I (the literal translation of Eikonoklastes is 'the image breaker'), the exiled Charles II and his party published a defence of monarchy, Defensio Regia pro Carolo Primo, written by the leading humanist Claudius Salmasius. By January of the following year, Milton was ordered to write a defence of the English people by the Council of State. Given the European audience and the English Republic's desire to establish diplomatic and cultural legitimacy, Milton worked more slowly than usual, as he drew on the learning marshalled by his years of study to compose a riposte. On 24 February 1652, Milton published his Latin defence of the English People, Defensio pro Populo Anglicano, also known as the First Defence. Milton's pure Latin prose and evident learning, exemplified in the First Defence, quickly made him a European reputation, and the work ran to numerous editions.[34] He also published in 1652 his Sonnet 16 in praise of "Cromwell, our cheif of men".

.jpg)

In 1654, in response to an anonymous Royalist tract "Regii sanguinis clamor", a work that made many personal attacks on Milton, he completed a second defence of the English nation, Defensio secunda, which praised Oliver Cromwell, now Lord Protector, while exhorting him to remain true to the principles of the Revolution. Alexander Morus, to whom Milton wrongly attributed the Clamor (in fact by Peter du Moulin), published an attack on Milton, in response to which Milton published the autobiographical Defensio pro se in 1655. In addition to these literary defences of the Commonwealth and his character, Milton continued to translate official correspondence into Latin. By 1654, Milton had become totally blind; the cause of his blindness is debated but bilateral retinal detachment or glaucoma are most likely.[36] His blindness forced him to dictate his verse and prose to amanuenses (helpers), one of whom was the poet Andrew Marvell. One of his best-known sonnets, On His Blindness, is presumed to date from this period.

The Restoration

Though Cromwell's death in 1658 caused the English Republic to collapse into feuding military and political factions, Milton stubbornly clung to the beliefs that had originally inspired him to write for the Commonwealth. In 1659, he published A Treatise of Civil Power, attacking the concept of a state-dominated church (the position known as Erastianism), as well as Considerations touching the likeliest means to remove hirelings, denouncing corrupt practises in church governance. As the Republic disintegrated, Milton wrote several proposals to retain a non-monarchical government against the wishes of parliament, soldiers and the people.

- A Letter to a Friend, Concerning the Ruptures of the Commonwealth, written in October 1659, was a response to General Lambert's recent dissolution of the Rump Parliament.

- Proposals of certain expedients for the preventing of a civil war now feared, written in November 1659.

- The Ready and Easy Way to Establishing a Free Commonwealth, in two editions, responded to General Monck's march towards London to restore the Long Parliament (which led to the restoration of the monarchy). The work is an impassioned, bitter, and futile jeremiad damning the English people for backsliding from the cause of liberty and advocating the establishment of an authoritarian rule by an oligarchy set up by unelected parliament.

Upon the Restoration in May 1660, Milton went into hiding for his life, while a warrant was issued for his arrest and his writings burnt. He re-emerged after a general pardon was issued, but was nevertheless arrested and briefly imprisoned before influential friends, such as Marvell, now an MP, intervened. On 24 February 1663, Milton remarried, for a third and final time, a Wistaston, Cheshire-born woman, Elizabeth (Betty) Minshull, then aged 24, and spent the remaining decade of his life living quietly in London, only retiring to a cottage—Milton's Cottage—in Chalfont St. Giles, his only extant home, during the Great Plague of London.

During this period, Milton published several minor prose works, such as a grammar textbook, Art of Logic, and a History of Britain. His only explicitly political tracts were the 1672 Of True Religion, arguing for toleration (except for Catholics), and a translation of a Polish tract advocating an elective monarchy. Both these works were referred to in the Exclusion debate—the attempt to exclude the heir presumptive, James, Duke of York, from the throne of England because he was Roman Catholic—that would preoccupy politics in the 1670s and 80s and precipitate the formation of the Whig party and the Glorious Revolution.

Milton died of kidney failure on 8 November 1674 and was buried in the church of St Giles Cripplegate, Fore Street, London.[37] According to an early biographer, his funeral was attended by “his learned and great Friends in London, not without a friendly concourse of the Vulgar.”[38] A monument by John Bacon the Elder was added in 1793.

Family

Milton and his first wife, Mary Powell (1625–1652) had four children:

- Anne (born 7 July 1646)

- Mary (born 25 October 1648)

- John (16 March 1651 – June 1652)

- Deborah (2 May 1652 – ?)

Mary Powell died on 5 May 1652 from complications following Deborah's birth. Milton's daughters survived to adulthood, but he had always a strained relationship with them.

On 12 November 1656, Milton was married again, to Katherine Woodcock. She died on 3 February 1658, less than four months after giving birth to a daughter, Katherine, who also died.

Milton married for a third time on 24 February 1662, to Elizabeth Mynshull (1638–1728), the niece of Thomas Mynshull, a wealthy apothecary and philanthropist in Manchester. Despite a 31-year age gap, the marriage seemed happy, according to John Aubrey, and was to last more than 12 years until Milton's death. (A plaque on the wall of Mynshull's House in Manchester describes Elizabeth as Milton's "3rd and Best wife".) Samuel Johnson, however, claims that Mynshull was "a domestic companion and attendant" and that Milton's nephew, Edward Phillips, relates that Mynshull "oppressed his children in his lifetime, and cheated them at his death".[39]

Two nephews (sons of Milton's sister Anne), Edward and John Phillips, were educated by Milton and became writers themselves. John acted as a secretary, and Edward was Milton's first biographer.

Poetry

Milton's poetry was slow to see the light of day, at least under his name. His first published poem was On Shakespear (1630), anonymously included in the Second Folio edition of William Shakespeare. In the midst of the excitement attending the possibility of establishing a new English government, Milton collected his work in 1645 Poems. The anonymous edition of Comus was published in 1637, and the publication of Lycidas in 1638 in Justa Edouardo King Naufrago was signed J. M. Otherwise, the 1645 collection was the only poetry of his to see print, until Paradise Lost appeared in 1667.

Paradise Lost

Milton's magnum opus, the blank-verse epic poem Paradise Lost, was composed by the blind and impoverished Milton from 1658 to 1664 (first edition) with small but significant revisions published in 1674 (second edition). As a blind poet, Milton dictated his verse to a series of aides in his employ. It has been argued that the poem reflects his personal despair at the failure of the Revolution, yet affirms an ultimate optimism in human potential. Some literary critics have argued that Milton encoded many references to his unyielding support for the "Good Old Cause".[40]

On 27 April 1667,[41] Milton sold the publication rights to Paradise Lost to publisher Samuel Simmons for £5, equivalent to approximately £7,400 income in 2008,[42] with a further £5 to be paid if and when each print run of between 1,300 and 1,500 copies sold out.[43] The first run, a quarto edition priced at three shillings per copy, was published in August 1667 and sold out in eighteen months.[44]

Milton followed up Paradise Lost with its sequel, Paradise Regained, published alongside the tragedy Samson Agonistes, in 1671. Both these works also resonate with Milton's post-Restoration political situation. Just before his death in 1674, Milton supervised a second edition of Paradise Lost, accompanied by an explanation of "why the poem rhymes not" and prefatory verses by Marvell. Milton republished his 1645 Poems in 1673, as well a collection of his letters and the Latin prolusions from his Cambridge days. A 1668 edition of Paradise Lost, reported to have been Milton's personal copy, is now housed in the archives of the University of Western Ontario.

Views

An unfinished religious manifesto, De doctrina christiana, probably written by Milton, lays out many of his heterodox theological views, and was not discovered and published until 1823. Milton's key beliefs were idiosyncratic, not those of an identifiable group or faction, and often they go well beyond the orthodoxy of the time. Their tone, however, stemmed from the Puritan emphasis on the centrality and inviolability of conscience.[45] He was his own man, but it is Areopagitica, where he was anticipated by Henry Robinson and others, that has lasted best of his prose works.

Philosophy

By the late 1650s, Milton was a proponent of monism or animist materialism, the notion that a single material substance which is "animate, self-active, and free" composes everything in the universe: from stones and trees and bodies to minds, souls, angels, and God.[46] Milton devised this position to avoid the mind-body dualism of Plato and Descartes as well as the mechanistic determinism of Hobbes. Milton's monism is most notably reflected in Paradise Lost when he has angels eat (5.433–39) and engage in sexual intercourse (8.622–29) and the De Doctrina, where he denies the dual natures of man and argues for a theory of Creation ex Deo.

Political thought

In his political writing, Milton addressed particular themes at different periods. The years 1641–42 were dedicated to church politics and the struggle against episcopacy. After his divorce writings, Areopagitica, and a gap, he wrote in 1649–54 in the aftermath of the execution of Charles I, and in polemic justification of the regicide and the existing Parliamentarian regime. Then in 1659–60 he foresaw the Restoration, and wrote to head it off.[47]

Milton's own beliefs were in some cases both unpopular and dangerous, and this was true particularly to his commitment to republicanism. In coming centuries, Milton would be claimed as an early apostle of liberalism.[48] According to James Tully:

... with Locke as with Milton, republican and contraction conceptions of political freedom join hands in common opposition to the disengaged and passive subjection offered by absolutists such as Hobbes and Robert Filmer.[49]

A friend and ally in the pamphlet wars was Marchamont Nedham. Austin Woolrych considers that although they were quite close, there is "little real affinity, beyond a broad republicanism", between their approaches.[50] Blair Worden remarks that both Milton and Nedham, with others such as Andrew Marvell and James Harrington, would have taken the problem with the Rump Parliament to be not the republic, but the fact that it was not a proper republic.[51] Woolrych speaks of "the gulf between Milton's vision of the Commonwealth's future and the reality".[52] In the early version of his History of Britain, begun in 1649, Milton was already writing off the members of the Long Parliament as incorrigible.[53]

He praised Oliver Cromwell as the Protectorate was set up; though subsequently he had major reservations. When Cromwell seemed to be backsliding as a revolutionary, after a couple of years in power, Milton moved closer to the position of Sir Henry Vane, to whom he wrote a sonnet in 1652.[54][55] The group of disaffected republicans included, besides Vane, John Bradshaw, John Hutchinson, Edmund Ludlow, Henry Marten, Robert Overton, Edward Sexby and John Streater; but not Marvell, who remained with Cromwell's party.[56] Milton had already commended Overton, along with Edmund Whalley and Bulstrode Whitelocke, in Defensio Secunda.[57] Nigel Smith writes that

... John Streater, and the form of republicanism he stood for, was a fulfilment of Milton's most optimistic ideas of free speech and of public heroism [...][58]

As Richard Cromwell fell from power, he envisaged a step towards a freer republic or “free commonwealth”, writing in the hope of this outcome in early 1660. Milton had argued for an awkward position, in the Ready and Easy Way, because he wanted to invoke the Good Old Cause and gain the support of the republicans, but without offering a democratic solution of any kind.[59] His proposal, backed by reference (amongst other reasons) to the oligarchical Dutch and Venetian constitutions, was for a council with perpetual membership. This attitude cut right across the grain of popular opinion of the time, which swung decisively behind the restoration of the Stuart monarchy that took place later in the year.[60] Milton, an associate of and advocate on behalf of the regicides, was silenced on political matters as Charles II returned.

Theology

Like many Renaissance artists before him, Milton attempted to integrate Christian theology with classical modes. In his early poems, the poet narrator expresses a tension between vice and virtue, the latter invariably related to Protestantism. In Comus, Milton may make ironic use of the Caroline court masque by elevating notions of purity and virtue over the conventions of court revelry and superstition. In his later poems, Milton's theological concerns become more explicit.

Milton embraced many heterodox Christian theological views. He rejected the Trinity, in the belief that the Son was subordinate to the Father, a position known as Arianism; and his sympathy or curiosity was probably engaged by Socinianism: in August 1650 he licensed for publication by William Dugard the Racovian Catechism, based on a non-trinitarian creed.[61][62] A source has interpreted him as broadly Protestant, if not always easy to locate in a more precise religious category.

In his 1641 treatise, Of Reformation, Milton expressed his dislike for Catholicism and episcopacy, presenting Rome as a modern Babylon, and bishops as Egyptian taskmasters. These analogies conform to Milton's puritanical preference for Old Testament imagery. He knew at least four commentaries on Genesis: those of John Calvin, Paulus Fagius, David Pareus and Andreus Rivetus.[63]

Through the Interregnum, Milton often presents England, rescued from the trappings of a worldly monarchy, as an elect nation akin to the Old Testament Israel, and shows its leader, Oliver Cromwell, as a latter-day Moses. These views were bound up in Protestant views of the Millennium, which some sects, such as the Fifth Monarchists predicted would arrive in England. Milton, however, would later criticise the "worldly" millenarian views of these and others, and expressed orthodox ideas on the prophecy of the Four Empires.[64]

The Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660 began a new phase in Milton's work. In Paradise Lost, Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes, Milton mourns the end of the godly Commonwealth. The Garden of Eden may allegorically reflect Milton's view of England's recent Fall from Grace, while Samson's blindness and captivity—mirroring Milton's own lost sight—may be a metaphor for England's blind acceptance of Charles II as king. Illustrated by Paradise Lost is mortalism, the belief that the soul lies dormant after the body dies.[65]

Despite the Restoration of the monarchy, Milton did not lose his personal faith; Samson shows how the loss of national salvation did not necessarily preclude the salvation of the individual, while Paradise Regained expresses Milton's continuing belief in the promise of Christian salvation through Jesus Christ.

Though he may have maintained his personal faith in spite of the defeats suffered by his cause, the Dictionary of National Biography recounted how he had been alienated from the Church of England by Archbishop William Laud, and then moved similarly from the Dissenters by their denunciation of religious tolerance in England.

Milton had come to stand apart from all sects, though apparently finding the Quakers most congenial. He never went to any religious services in his later years. When a servant brought back accounts of sermons from nonconformist meetings, Milton became so sarcastic that the man at last gave up his place.

Religious toleration

Milton called in the Areopagitica for "the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties" (applied, however, only to the conflicting Protestant sects, and not to atheists, Jews, Muslims or Catholics[66]). "Milton argued for disestablishment as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration. Rather than force a man's conscience, government should recognise the persuasive force of the gospel."[67]

Divorce

Milton wrote The Doctrine & Discipline of Divorce in 1643, at the beginning of the English Civil War. In August of that year, he presented his thoughts to the Westminster Assembly of divines, which had been created by the Long Parliament to bring greater reform to the Church of England. The Assembly convened on 1 July against the will of King Charles I.

Milton's thinking on divorce caused him considerable trouble with the authorities. An orthodox Presbyterian view of the time was that Milton's views on divorce constituted a one-man heresy:

The fervently Presbyterian Edwards had included Milton’s divorce tracts in his list in Gangraena of heretical publications that threatened the religious and moral fabric of the nation; Milton responded by mocking him as “shallow Edwards” in the satirical sonnet “On the New Forcers of Conscience under the Long Parliament”, usually dated to the latter half of 1646.[68]

Even here, though, his originality is qualified: Thomas Gataker had already identified "mutual solace" as a principal goal in marriage.[69] Milton abandoned his campaign to legitimise divorce after 1645, but he expressed support for polygamy in the De Doctrina Christiana, the theological treatise that provides the clearest evidence for his views.[70]

Milton wrote during a period when thoughts about divorce were anything but simplistic; rather, there was active debate among thought-leaders. However, Milton's basic approval of divorce within strict parameters set by the biblical witness was typical of many influential Christian intellectuals, particularly the Westminster divines. Milton addressed the Assembly on the matter of divorce in August 1643,[71] at a moment when the Assembly was beginning to form its opinion on the matter. In the Doctrine & Discipline of Divorce, Milton argued that divorce was a private matter, not a legal or ecclesiastical one. Neither the Assembly nor Parliament condemned Milton or his ideas. In fact, when the Westminster Assembly wrote the Westminster Confession of Faith they allowed for divorce ('Of Marriage and Divorce,' Chapter 24, Section 5) in cases of infidelity or abandonment. Thus, the Christian community, at least a majority within the 'Puritan' sub-set, approved of Milton's views.

Nevertheless, reaction among Puritans to Milton's views on divorce was mixed. Herbert Palmer (Puritan) condemned Milton in the strongest possible language. Palmer, who was a member of the Westminster Assembly, wrote:

If any plead Conscience ... for divorce for other causes then Christ and His Apostles mention; Of which a wicked booke is abroad and uncensured, though deserving to be burnt, whose Author, hath been so impudent as to set his Name to it, and dedicate it to your selves ... will you grant a Toleration for all this? (The Glasse of God’s Providence Towards His Faithfull Ones, 1644, p. 54).[72]

Palmer expressed his disapproval in a sermon addressed to the Westminster Assembly. The Scottish commissioner Robert Baillie described Palmer's sermon as one “of the most Scottish and free sermons that ever I heard any where.”[73]

History

History was particularly important for the political class of the period, and Lewalski considers that Milton "more than most illustrates" a remark of Thomas Hobbes on the weight placed at the time on the classical Latin historical writers Tacitus, Livy, Sallust and Cicero, and their republican attitudes.[74] Milton himself wrote that "Worthy deeds are not often destitute of worthy relaters", in Book II of his History of Britain. A sense of history mattered greatly to him:[75]

The course of human history, the immediate impact of the civil disorders, and his own traumatic personal life, are all regarded by Milton as typical of the predicament he describes as "the misery that has bin since Adam".[76]

Legacy and influence

Once Paradise Lost was published, Milton's stature as epic poet was immediately recognised. He cast a formidable shadow over English poetry in the 18th and 19th centuries; he was often judged equal or superior to all other English poets, including Shakespeare. Very early on, though, he was championed by Whigs, and decried by Tories: with the regicide Edmund Ludlow he was claimed as an early Whig,[77] while the High Tory Anglican minister Luke Milbourne lumped Milton in with other "Agents of Darkness" such as John Knox, George Buchanan, Richard Baxter, Algernon Sidney and John Locke.[78]

Early reception of the poetry

John Dryden, an early enthusiast, in 1677 began the trend of describing Milton as the poet of the sublime.[79] Dryden's The State of Innocence and the Fall of Man: an Opera (1677) is evidence of an immediate cultural influence. In 1695, Patrick Hume became the first editor of Paradise Lost, providing an extensive apparatus of annotation and commentary, particularly chasing down allusions.[80]

In 1732, the classical scholar Richard Bentley offered a corrected version of Paradise Lost.[81] Bentley was considered presumptuous, and was attacked in the following year by Zachary Pearce. Christopher Ricks judges that, as critic, Bentley was both acute and wrong-headed, and "incorrigibly eccentric"; William Empson also finds Pearce to be more sympathetic to Bentley's underlying line of thought than is warranted.[82][83]

There was an early, partial translation of Paradise Lost into German by Theodore Haak, and based on that a standard verse translation by Ernest Gottlieb von Berge. A subsequent prose translation by Johann Jakob Bodmer was very popular; it influenced Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock. The German-language Milton tradition returned to England in the person of the artist Henry Fuseli.

Many enlightenment thinkers of the 18th century revered and commented on Milton's poetry and non-poetical works. In addition to John Dryden, among them were Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, Thomas Newton, and Samuel Johnson. For example, in The Spectator,[84] Joseph Addison wrote extensive notes, annotations, and interpretations of certain passages of Paradise Lost. Jonathan Richardson, senior, and Jonathan Richardson, the younger, co-wrote a book of criticism.[85] In 1749, Thomas Newton published an extensive edition of Milton's poetical works with annotations provided by himself, Dryden, Pope, Addison, the Richardsons (father and son) and others. Newton's edition of Milton was a culmination of the honour bestowed upon Milton by early Enlightenment thinkers; it may also have been prompted by Richard Bentley's infamous edition, described above. Samuel Johnson wrote numerous essays on Paradise Lost, and Milton was included in his Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets (1779–1781).

Blake

William Blake considered Milton the major English poet. Blake placed Edmund Spenser as Milton's precursor, and saw himself as Milton's poetical son.[86] In his Milton a Poem, Blake uses Milton as a character.

Romantic theory

Edmund Burke was a theorist of the sublime, and he regarded Milton's description of Hell as exemplary of sublimity as an aesthetic concept. For Burke, it was to set alongside mountain-tops, a storm at sea, and infinity.[87] In The Beautiful and the Sublime, he wrote: "No person seems better to have understood the secret of heightening, or of setting terrible things, if I may use the expression, in their strongest light, by the force of a judicious obscurity than Milton."[88]

The Romantic poets valued his exploration of blank verse, but for the most part rejected his religiosity. William Wordsworth began his sonnet "London, 1802" with "Milton! thou should'st be living at this hour"[89] and modelled The Prelude, his own blank verse epic, on Paradise Lost. John Keats found the yoke of Milton's style uncongenial;[90] he exclaimed that "Miltonic verse cannot be written but in an artful or rather artist's humour."[91] Keats felt that Paradise Lost was a "beautiful and grand curiosity", but his own unfinished attempt at epic poetry, Hyperion, was unsatisfactory to the author because, amongst other things, it had too many "Miltonic inversions".[91] In The Madwoman in the Attic, Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar note that Mary Shelley's novel Frankenstein is, in the view of many critics, "one of the key 'Romantic' readings of Paradise Lost."[92]

Later legacy

The Victorian age witnessed a continuation of Milton's influence, George Eliot[93] and Thomas Hardy being particularly inspired by Milton's poetry and biography. Hostile 20th-century criticism by T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound did not reduce Milton's stature.[94] F. R. Leavis, in The Common Pursuit, responded to the points made by Eliot, in particular the claim that "the study of Milton could be of no help: it was only a hindrance," by arguing, "As if it were a matter of deciding not to study Milton! The problem, rather, was to escape from an influence that was so difficult to escape from because it was unrecognized, belonging, as it did, to the climate of the habitual and 'natural'."[95] Harold Bloom, in The Anxiety of Influence, wrote that "Milton is the central problem in any theory and history of poetic influence in English [...]".[96]

Milton's Areopagitica is still cited as relevant to the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[97] A quotation from Areopagitica—"A good book is the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose to a life beyond life"—is displayed in many public libraries, including the New York Public Library.

The title of Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy is derived from a quotation, "His dark materials to create more worlds", line 915 of Book II in Paradise Lost. Pullman was concerned to produce a version of Milton's poem accessible to teenagers,[98] and has spoken of Milton as "our greatest public poet".[99]

T. S. Eliot believed that "of no other poet is it so difficult to consider the poetry simply as poetry, without our theological and political dispositions... making unlawful entry".[100]

Literary legacy

Milton's use of blank verse, in addition to his stylistic innovations (such as grandiloquence of voice and vision, peculiar diction and phraseology) influenced later poets. At the time, poetic blank verse was considered distinct from its use in verse drama, and Paradise Lost was taken as a unique examplar.[101] Said Isaac Watts in 1734, "Mr. Milton is esteemed the parent and author of blank verse among us".[102] "Miltonic verse" might be synonymous for a century with blank verse as poetry, a new poetic terrain independent from both the drama and the heroic couplet.

Lack of rhyme was sometimes taken as Milton's defining innovation. He himself considered the rhymeless quality of Paradise Lost to be an extension of his own personal liberty:

This neglect then of Rhime ... is to be esteem'd an example set, the first in English, of ancient liberty recover'd to heroic Poem from the troublesom and modern bondage of Rimeing.[103]

This pursuit of freedom was largely a reaction against conservative values entrenched within the rigid heroic couplet.[104] Within a dominant culture that stressed elegance and finish, he granted primacy to freedom, breadth and imaginative suggestiveness, eventually developed into the romantic vision of sublime terror. Reaction to Milton's poetic worldview included, grudgingly, acknowledgement that of poet's resemblance to classical writers (Greek and Roman poetry being unrhymed). Blank verse came to be a recognised medium for religious works and for translations of the classics. Unrhymed lyrics like Collins' Ode to Evening (in the meter of Milton's translation of Horace's Ode to Pyrrha) were not uncommon after 1740.[105]

A second aspect of Milton's blank verse was the use of unconventional rhythm:

His blank-verse paragraph, and his audacious and victorious attempt to combine blank and rhymed verse with paragraphic effect in Lycidas, lay down indestructible models and patterns of English verse-rhythm, as distinguished from the narrower and more strait-laced forms of English metre.[106]

Before Milton, "the sense of regular rhythm ... had been knocked into the English head so securely that it was part of their nature".[107] The "Heroick measure", according to Samuel Johnson, "is pure ... when the accent rests upon every second syllable through the whole line The repetition of this sound or percussion at equal times, is the most complete harmony of which a single verse is capable",[108] Caesural pauses, most agreed, were best placed at the middle and the end of the line. In order to support this symmetry, lines were most often octo- or deca-syllabic, with no enjambed endings. To this schema Milton introduced modifications, which included hypermetrical syllables (trisyllabic feet), inversion or slighting of stresses, and the shifting of pauses to all parts of the line.[109] Milton deemed these features to be reflective of "the transcendental union of order and freedom".[110] Admirers remained hesitant to adopt such departures from traditional metrical schemes: “The English ... had been writing separate lines for so long that they could not rid themselves of the habit”.[111] Isaac Watts preferred his lines distinct from each other, as did Oliver Goldsmith, Henry Pemberton, and Scott of Amwell, whose general opinion it was that Milton's frequent omission of the initial unaccented foot was "displeasing to a nice ear".[112] It was not until the late 18th century that poets (beginning with Gray) began to appreciate "the composition of Milton's harmony ... how he loved to vary his pauses, his measures, and his feet, which gives that enchanting air of freedom and wilderness to his versification".[113]

While neo-classical diction was as restrictive as its prosody, and narrow imagery paired with uniformity of sentence structure resulted in a small set of 800 nouns circumscribing the vocabulary of 90% of heroic couplets ever written up to the eighteenth century,[114] and tradition required that the same adjectives attach to the same nouns, followed by the same verbs, Milton's pursuit of liberty extended into his vocabulary as well. It included many Latinate neologisms, as well as obsolete words already dropped from popular usage so completely that their meanings were no longer understood. In 1740, Francis Peck identified some examples of Milton's "old" words (now popular).[115] The “Miltonian dialect” as it was called, was emulated by later poets; Pope used the diction of Paradise Lost in his Homer translation, while the lyric poetry of Gray and Collins was frequently criticised for their use of “obsolete words out of Spenser and Milton”.[116] The language of Thomson's finest poems (e.g. The Seasons, Castle of Indolence) was self-consciously modelled after the Miltonian dialect, with the same tone and sensibilities as Paradise Lost. Following to Milton, English poetry from Pope to John Keats exhibited a steadily increasing attention to the connotative, the imaginative and poetic, value of words.[117]

Works

Poetry and drama

- 1631: L'Allegro

- 1631: Il Penseroso

- 1634: A Mask Presented at Ludlow Castle, 1634 commonly known as Comus (a masque)

- 1638: Lycidas

- 1645: Poems of Mr John Milton, Both English and Latin

- 1655: On the Late Massacre in Piedmont

- 1667: Paradise Lost

- 1671: Paradise Regained

- 1671: Samson Agonistes

- 1673: Poems, &c, Upon Several Occasions

Prose

- Of Reformation (1641)

- Of Prelatical Episcopacy (1641)

- Animadversions (1641)

- The Reason of Church-Government Urged against Prelaty (1642)

- Apology for Smectymnuus (1642)

- Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce (1643)

- Judgement of Martin Bucer Concerning Divorce (1644)

- Of Education (1644)

- Areopagitica (1644)

- Tetrachordon (1645)

- Colasterion (1645)

- The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates (1649)

- Eikonoklastes (1649)

- Defensio pro Populo Anglicano [First Defence] (1651)

- Defensio Secunda [Second Defence] (1654)

- A Treatise of Civil Power (1659)

- The Likeliest Means to Remove Hirelings from the Church (1659)

- The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth (1660)

- Brief Notes Upon a Late Sermon (1660)

- Accedence Commenced Grammar (1669)

- History of Britain (1670)

- Artis logicae plenior institutio [Art of Logic] (1672)

- Of True Religion (1673)

- Epistolae Familiaries (1674)

- Prolusiones (1674)

- A brief History of Moscovia, and other less known Countries lying Eastward of Russia as far as Cathay, gathered from the writings of several Eye-witnesses (1682)[118]

- De Doctrina Christiana (1823)

Notes

- ↑ McCalman 2001 p. 605.

- ↑ Contemporary Literary Criticism. "Milton, John – Introduction".

- ↑ Murphy, Arthur (1837). The Works of Samuel Johnson, LL. D.: An essay on the life and genius of Samuel Johnson. New York, NY: George Dearborn.

- ↑ Masson 1859 pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Forsyth, Neil (2008). "St. Paul's". John Milton A Biography (1st ed.). Wilkinson House, Jordan Hill Road, Oxford OX2 8DR, England: Lion Hudson. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7459-5310-6.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 p. 3.

- ↑ Skerpan-Wheeler, Elizabeth. "John Milton." British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500-1660: Second Series. Ed. Edward A. Malone. Detroit: Gale, 2003. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 281. Literature Resource Center.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dick 1962 pp. 270–5.

- ↑ "Milton, John (MLTN624J)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Hunter 1980 p. 99.

- ↑ Wedgwood 1961 p. 178.

- ↑ Hill 1977 p. 34.

- ↑ Pfeiffer 1955 pp. 363–373.

- ↑ Milton 1959 pp. 887–8.

- ↑ Johnson 1826 Vol. I. p. 64.

- ↑ Hill 1977 p. 38.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 p. 103.

- ↑ Chaney 1985 and 2000.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Milton 1959 Vol. IV part I. pp. 615–617.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 pp. 88–94.

- ↑ Chaney 1985 and 2000 and Lewalski p. 96.

- ↑ Chaney 1985 p. 244–51 and Chaney 2000 p. 313.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 pp. 94–98.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 p. 98.

- ↑ Milton 1959 Vol. IV part I pp. 618–619.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 pp. 99–109.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Campbell, Gordon (2004). "Milton, John (1608–1674)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18800. Retrieved 2013-10-25. (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ↑ Lobel 1957 pp. 122–134.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003 pp. 181–82, 600.

- ↑ Ann Hughes, 'Milton, Areopagitica, and the Parliamentary Cause', The Oxford Handbook of Milton, ed. Nicholas McDowell and Nigel Smith, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ↑ Blair Hoxby, 'Areopagitica and Liberty', The Oxford Handbook of Milton, ed. Nicholas McDowell and Nigel Smith, Oxford University Press, 2009

- ↑ C. Sullivan, 'Milton and the Beginning of Civil Service', in Literature in the Public Service (2013), Ch. 2.

- ↑ von Maltzahn 1999 p. 239.

- ↑

Stephen, Leslie (1894). "Milton, John (1608-1674)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 38. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Stephen, Leslie (1894). "Milton, John (1608-1674)". In Lee, Sidney. Dictionary of National Biography 38. London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ Sorsby, A. (1930). "On The Nature Of Milton's Blindness". British Journal of Ophthalmology 14 (7): 339–54. doi:10.1136/bjo.14.7.339. PMC 511199. PMID 18168884.

- ↑ Hibbert, Christopher; Ben Weinreb; John Keay; Julia Keay. (2010). The London Encyclopaedia. London: Pan Macmillan. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

- ↑ Toland 1932 p. 193.

- ↑ Johnson 1826 Vol. I 86.

- ↑ Hill 1977.

- ↑ Lindenbaum, Peter (1995). "Authors and Publishers in the Late Seventeenth Century: New Evidence on their Relations". The Library (Oxford University Press). s6-17 (3): 250–269. doi:10.1093/library/s6-17.3.250. ISSN 0024-2160.

- ↑ MeasuringWorth, 2010, "Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present". Access date: 13 March 2011.

- ↑ Darbishire, Helen (October 1941). The Review of English Studies (Oxford University Press) 17 (68): 415–427. JSTOR 509858. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "John Milton's Paradise Lost". The Morgan Library & Museum. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- ↑ See, for instance, Barker, Arthur. Milton and the Puritan Dilemma, 1641–1660. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1942: 338 and passim; Wolfe, Don M. Milton in the Puritan Revolution. New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1941: 19.

- ↑ Stephen Fallon, Milton Among the Philosophers (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991), p. 81.

- ↑ Blair Worden, Literature and Politics in Cromwellian England: John Milton, Andrew Marvell and Marchamont Nedham (2007), p. 154.

- ↑ Milton and Republicanism, ed. David Armitage, Armand Himy, and Quentin Skinner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- ↑ James Tully, An Approach to Political Philosophy: Locke in Contexts (1993), p. 301.

- ↑ Austin Woolrych, Commonwealth to Protectorate (1982), p. 34.

- ↑ Worden p. 149.

- ↑ Austin Woolrych, Commonwealth to Protectorate (1982), p. 101.

- ↑ G. E. Aylmer (editor), The Interregnum: The Quest for Settlement 1646–1660 (1972), p. 17.

- ↑ Christopher Hill, God's Englishman (1972 edition), p. 200.

- ↑ "Online Library of Liberty – To S r Henry Vane the younger. – The Poetical Works of John Milton". Oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ↑ "John W. Creaser – Prosodic Style and Conceptions of Liberty in Milton and Marvell – Milton Quarterly 34:1". Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ↑ William Riley Parker and Gordon Campbell, Milton (1996), p. 444.

- ↑ Nigel Smith, Popular Republicanism in the 1650s: John Streater's 'heroick mechanics ', p. 154, in David Armitage, Armand Himy, Quentin Skinner (editors), Milton and Republicanism (1998).

- ↑ Blair Worden, Literature and Politics in Cromwellian England: John Milton, Andrew Marvell and Marchamont Nedham (2007), Ch. 14, Milton and the Good Old Cause.

- ↑ Austin Woolrych, Last Quest for Settlement 1657–1660, p. 202, in G. E. Aylmer (editor), The Interregnum: The Quest for Settlement 1646–1660 (1972), p. 17.

- ↑ Lewalski, Life of Milton, p. 253.

- ↑ William Bridges Hunter, A Milton Encyclopedia (1980), Vol. VIII, p. 13.

- ↑ Arnold Williams, Renaissance Commentaries on "Genesis" and Some Elements of the Theology of Paradise Lost, PMLA, Vol. 56, No. 1 (Mar. 1941), pp. 151–164.

- ↑ Walter S. H. Lim, John Milton, Radical Politics, and Biblical Republicanism (2006), p. 141.

- ↑ John Rogers, The Matter of Revolution (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), p. xi.

- ↑ Hill, C. Milton and the English Revolution. Faber & Faber. 1977. pp 155-157

- ↑ Hunter, William Bridges. A Milton Encyclopedia, Volume 8 (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1980). pp. 71, 72. ISBN 0-8387-1841-8.

- ↑ (PDF) Nicholas McDowell, Family Politics; Or, How John Phillips Read His Uncle's Satirical Sonnets, Milton Quarterly Vol. 42 Issue 1, pp. 1–21. Published online: 17 April 2008.

- ↑ Christopher Hill, Milton and the English Revolution" (1977), p. 127.

- ↑ John Milton, The Christian Doctrine in Complete Poems and Major Prose, ed. Merritt Hughes (Hackett: Indianapolis, 2003), pp. 994–1000; Leo Miller, John Milton among the Polygamophiles (New York: Loewenthal Press, 1974).

- ↑ http://www.dartmouth.edu/~milton/reading_room/ddd/book_1/notes.shtml

- ↑ Ernest Sirluck, “Introduction,” Complete Prose Works of John Milton, New Haven: Yale U. Press, 1959, II, 103

- ↑ Baillie, Letters and Journals, Edinburgh, 1841, II, 220.

- ↑ Lewalski, Life of Milton, p. 199.

- ↑ Nicholas Von Maltzahn, Milton's History of Britain: republican historiography in the English Revolution, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991

- ↑ Timothy Kenyon, Utopian Communism and Political Thought in Early Modern England (1989), p. 34.

- ↑ Kevin Sharpe, Remapping Early Modern England: The Culture of Seventeenth-century Politics (2000), p. 7.

- ↑ J. P. Kenyon, Revolution Principles (1977), p. 77.

- ↑ Al-Zubi, Hasan A. (2007). "Audience and human nature in the poetry of Milton and Dryden/Milton ve Dryden'in siirlerinde izleyici ve insan dogasi – Interactions – Find Articles at BNET". Findarticles.com. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- ↑ Joseph M. Levine, The Battle of the Books: History and Literature in the Augustan Age (1994), p. 247.

- ↑ "Online text of one book". Andromeda.rutgers.edu. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Christopher Ricks, Milton's Grand Style (1963), pp. 9, 14, 57.

- ↑ William Empson, Some Versions of Pastoral (1974 edition), p. 147.

- ↑ Nos 267, 273, 279, 285, 291, 297, 303, 309, 315, 321, 327, 333, 339, 345, 351, 357, 363, and 369.

- ↑ Explanatory Notes and Remarks on Milton's Paradise Lost (1734).

- ↑ S. Foster Damon, A Blake Dictionary (1973), p. 274.

- ↑ Bill Beckley, Sticky Sublime (2001), p. 63.

- ↑ Part II, Section I: Adelaide.edu.au.

- ↑ "Francis T. Palgrave, ed. (1824–1897). The Golden Treasury. 1875". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Thomas N. Corns, A Companion to Milton (2003), p. 474.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Leader, Zachary. "Revision and Romantic Authorship". Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. 298. ISBN 0-19-818634-7.

- ↑ Cited from the original in J. Paul Hunter (editor), Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1996), p. 225.

- ↑ Nardo, Anna K. George Eliot's Dialogue with Milton.

- ↑ Printz-Påhlson, Göran. Letters of Blood and Other Works in English. pp. 10-14

- ↑ Leavis, F. R. The Common Pursuit. http://books.google.com/books?id=9Yl1ax4_hukC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Harold Bloom, The Anxiety of Influence: A theory of poetry (1997), p. 33.

- ↑ "Milton's Areopagitica and the Modern First Amendment by Vincent Blasi". Nationalhumanitiescenter.org. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Imitating Milton: The Legacy of Paradise Lost". Christs.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ "Philip Pullman opens Bodleian Milton exhibition – University of Oxford". Ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Eliot 1947 p. 63.

- ↑ Saintsbury 1908 ii. 443.

- ↑ Watts 1810 iv. 619.

- ↑ Milton 1668 xi.

- ↑ Gordon 2008 p. 234.

- ↑ Dexter 1922 p. 46.

- ↑ Saintsbury 1908 ii. 457.

- ↑ Saintsbury 1916 p. 101.

- ↑ Johnson 1751 no. 86.

- ↑ Dexter 1922 p. 57.

- ↑ Saintsbury 1908 ii. 458–59.

- ↑ Dexter 1922 p. 59.

- ↑ Saintsbury 1916 p. 114.

- ↑ Gray 1748 Observations on English Metre.

- ↑ Hobsbaum 1996 p. 40.

- ↑ They included "self-same", "hue", "minstrelsy", "murky", "carol", and "chaunt". Among Milton's naturalized Latin words were "humid", "orient", "hostil", "facil", "fervid", "jubilant", "ire", "bland", "reluctant", "palpable", "fragil", and "ornate". Peck 1740 pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Scott 1785 63.

- ↑ Saintsbury 1908 ii. 468.

- ↑ "Online Library of Liberty – Titles". Oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

References

- Beer, Anna. Milton: Poet, Pamphleteer, and Patriot. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2008.

- Campbell, Gordon and Corns, Thomas. John Milton: Life, Work, and Thought. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Chaney, Edward, The Grand Tour and the Great Rebellion: Richard Lassels and 'The Voyage of Italy' in the Seventeenth Century (Geneva, CIRVI, 1985) and "Milton's Visit to Vallombrosa: A literary tradition", The Evolution of the Grand Tour, 2nd ed (Routledge, London, 2000).

- Dexter, Raymond. The Influence of Milton on English Poetry. London: Kessinger Publishing. 1922

- Dick, Oliver Lawson. Aubrey's Brief Lives. Harmondsworth, Middl.: Penguin Books, 1962.

- Eliot, T. S. "Annual Lecture on a Master Mind: Milton", Proceedings of the British Academy 33 (1947).

- Fish, Stanley. Versions of Antihumanism: Milton and Others. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1-107-00305-7.

- Gray, Thomas. Observations on English Metre. "The Works of Thomas Gray". ed. Mitford. London: William Pickering, 1835.

- Hawkes, David, John Milton: A Hero of Our Time (Counterpoint Press: London and New York, 2009) ISBN 1582434379

- Hill, Christopher. Milton and the English Revolution. London: Faber, 1977.

- Hobsbaum, Philip. "Meter, Rhythm and Verse Form". New York: Routledge, 1996.

- Hunter, William Bridges. A Milton Encyclopedia. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, 1980.

- Johnson, Samuel. "Rambler #86" 1751.

- Johnson, Samuel. Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets. London: Dove, 1826.

- Leonard, John. Faithful Labourers: A Reception History of Paradise Lost, 1667-1970. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Lewalski, Barbara K. The Life of John Milton. Oxford: Blackwells Publishers, 2003.

- A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 5: Bullingdon Hundred. 1957. pp. 122–134.

- Masson, David. The Life of John Milton and History of His Time, Vol. 1. Cambridge: 1859.

- McCalman, Iain. et al., An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture, 1776–1832. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Milner, Andrew. John Milton and the English Revolution: A Study in the Sociology of Literature. London: Macmillan, 1981.

- Milton, John. Complete Prose Works 8 Vols. gen. ed. Don M. Wolfe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959.

- Milton, John. The Verse, "Paradise Lost". London, 1668.

- Peck, Francis. "New Memoirs of Milton". London, 1740.

- Pfeiffer, Robert H. "The Teaching of Hebrew in Colonial America", The Jewish Quarterly Review (April 1955).

- Rosenfeld, Nancy. The Human Satan in Seventeenth-Century English Literature: From Milton to Rochester. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008.

- Saintsbury, George. "The Peace of the Augustans: A Survey of Eighteenth Century Literature as a Place of Rest and Refreshment". London: Oxford University Press. 1946.

- Saintsbury, George. "A History of English Prosody: From the Twelfth Century to the Present Day". London: Macmillan and Co., 1908.

- Scott, John. "Critical Essays". London, 1785.

- Stephen, Leslie (1902). "New Lights on Milton". Studies of a Biographer 4. London: Duckworth & Co. pp. 86–129.

- Sullivan, Ceri. Literature in the Public Service: Divine Bureaucracy (2013).

- Toland, John. Life of Milton in The Early Lives of Milton. Ed. Helen Darbishere. London: Constable, 1932.

- von Maltzahn, Nicholas. "Milton's Readers" in The Cambridge Companion to Milton. ed. Dennis Richard Danielson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Watts, Isaac. "Miscellaneous Thoughts" No. lxxiii. Works 1810

- Wedgwood, C. V. Thomas Wentworth, First Earl of Strafford 1593–1641. New York: Macmillan, 1961.

- Wilson, A. N. The Life of John Milton. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Milton. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: John Milton |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: John Milton |

- Works by John Milton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Milton at Internet Archive

- Works by John Milton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Biography of John Milton Encyclopædia Britannica

- "The masque in Milton's Arcades and Comus" by Gilbert McInnis

- Milton's cottage

- Famous quotations

- Site dedicated to Milton

- Books on Milton's life and works

- Open Milton – an open set of Milton's works, together with ancillary information and tools, in a form designed for reuse, launched on Milton's 400th Birthday by the Open Knowledge Foundation

- Milton Reading Room – online, almost fully annotated, collection of all of Milton's poetry and selections of his prose

- Milton-L Homepage – a scholarly website devoted to the life, literature and times of Milton. It hosts the webpage for the Milton Society of America, as well as the Milton listserv, an Internet discussion group for Milton.

- John Milton index entry at Poets' Corner

- Milton 400th Anniversary – lots of Milton material and details of the Milton 400th Anniversary Celebrations, from Christ's College, Cambridge, where Milton studied

- Thomas Ellwood's Epitaph for John Milton

- A common-place book of John Milton, and a Latin essay and Latin verses presumed to be by Milton. Cornell University Library Historical Monographs Collection. {Reprinted by} Cornell University Library Digital Collections

- "John Milton-poet or politician?" on BBC Radio 4's In Our Time, featuring John Carey, Lisa Jardine, Blair Worden

- Heroic Milton: Happy Birthday - Frank Kermode in The New York Review of Books

- Audio: Robert Pinsky reads "Methought I Saw My Late Espoused Saint" by John Milton (via poemsoutloud.net)

- Timeline of the Life and Works of Milton at The Online Library Of Liberty

- Areopagitica (Jebb ed.) [1664]. See original text in The Online Library Of Liberty.

- The Poetical Works of John Milton, edited after the Original Texts by the Rev. H.C. Beeching M.A. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1900). See original text in The Online Library Of Liberty.

- The Prose Works of John Milton: With a Biographical Introduction by Rufus Wilmot Griswold. In Two Volumes (Philadelphia: John W. Moore, 1847). See original text in The Online Library Of Liberty.

- The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth, edited with Introduction, Notes, and Glossary by Evert Mordecai Clark (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1915). See original text in The Online Library Of Liberty

- Online exhibition at Christ's College celebrating the 400th anniversary of Milton's birth

- The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates, edited with Introduction and Notes by William Talbot Allison (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1911). See original text in The Online Library Of Liberty.

- Australian radio interview, Stephen Fallon and Nigel Smith on Milton at 400

- Australian radio feature on John Milton at 400

- L'Allegro, Il Penseroso, Comus and other John Milton's works in HTML format.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||