John Marshall (publisher)

| John Marshall (publisher) | |

|---|---|

|

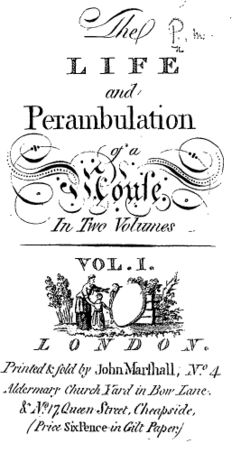

Title page from Dorothy Kilner's Life and Perambulation of a Mouse, with one of Marshall's imprints | |

| Born |

Baptized November 28, 1756, London, St Mary Aldermary |

| Died |

July 1824 London |

| Occupation | Publisher, printer, printseller |

| Spouse(s) | Eleanor Marshall |

| Children | Eleanor Elizabeth Marshall, John Marshall jnr. |

| Parent(s) | Richard Marshall (printer, publisher, printseller) and Ellenor Marshall |

- For other people named John Marshall, see John Marshall (disambiguation).

John Marshall (1756–1824) was a London publisher who specialized in children's literature, chapbooks, educational games and teaching schemes. He described himself as "The Children's Printer" and referred to children as his "young friends"[1] He was the preeminent children's book publisher in England from about 1780 until 1800.[2] After 1795 he became the publisher of Hannah More's Cheap Repository Tracts, and following a dispute with More he published his own similar series. About 1800 Marshall began to publish a series of miniature libraries, games and picture books for children. He died in July 1824 and his business was continued either by his widow or his unmarried daughter, both of whom were named Eleanor.

Life

John Marshall was baptized 28 November 1756 in the parish church of St Mary Aldermary, London, the son of Richard Marshall (fl 1752–1779) and his wife Ellenor.[3] His father was a junior partner, then full partner, and subsequently owner of the successful chapbook and popular print business at No. 4 Aldermary Churchyard, (off Watling Street), that had been established in 1755 by William and Cluer Dicey. He was bound apprentice to the printer Edward Gilberd of Watling Street 3 September 1771, but transferred to his father's business a year later, and became a freeman of the Stationers’ Company 6 October 1778.[4] He inherited his father's business the following year.

John married Eleanor Blashfield 4 December 1788; they had two children, Eleanor Elizabeth born 8 March 1790 and John born 28 May 1792.[3] He died during the summer of 1824.[5]

History of the business

Richard Marshall left 50% of his business to his son John, and 25% each to his nephew James and his widow.[6] It continued to operate as John Marshall and Co. until November 1789 when the partnership was voluntarily wound up and John continued in business on his own.[7] In October 1806 Marshall moved his business to 140 Fleet Street,[8] where it remained until his death in 1824. According to his will (made in 1813) his business was to be left to his widow Eleanor Marshall, but probate was granted on 14 July 1824 to his unmarried daughter Eleanor Elizabeth Marshall.[9] One of these ladies was the "E. Marshall" who continued to operate the business until c. 1829.

Street literature

Richard's business was based on the sale of popular prints, maps, chapbooks, broadside ballads and other forms of street literature.[10] These publications continued to represent an important part of the output of the press until the mid-1790s. There are examples of all of these categories of literature which contain John Marshall's imprint, but the extent of his involvement is difficult to ascertain as many of these works were undated and carried the imprint 'Printed and sold in Aldermary Churchyard'.

Children's literature

During the 1770s Richard had begun to publish children's books as a sideline, and this aspect of the work was greatly expanded by John and his partners after 1780. Marshall recruited a number of new female authors and published some of the most important children's literature of the time,[11] notably:

- Mary Ann Kilner – The adventures of a pincushion, The adventures of a whipping-top, Jemima Placid, Memoirs of a peg-top, or William Sedley;

- Dorothy Kilner – Anecdotes of a boarding-school, The histories of more children than one, The life and perambulation of a mouse, The Rotchfords;

- Ellenor Fenn (Mrs Teachwell) – Cobwebs to catch flies, Fables in monosyllables, The mother's grammar, The rational dame, Rational sports, School occurrences;

- Sarah Trimmer – Scripture lessons, various series of prints depicting biblical and historical scenes, with accompanying descriptions, for use in Sunday and other schools.

- Lucy Peacock – The life of a bee, Emily; or, The test of sincerity

All of these works all went through several editions; some went through innumerable editions, and remained in print well into the 19th century – such as Cobwebs to catch flies or The life and perambulation of a mouse, which was praised by Sarah Trimmer and Mary Wollstonecraft alike.[12]

Marshall's catalogue for May 1793 listed 113 children's book titles, two children's magazines, as well as various teaching aids.[13]

Teaching aids

Marshall ventured into the publication of teaching aids c.1785 with Mrs Teachwell's Set of Toys, for enabling Ladies to instill the Rudiments of Spelling, Reading, Grammar, and Arithmetic, under the Idea of Amusement, which was accompanied by an instruction manual 'The Art of teaching in sport.[14] Other teaching aids listed in the 1793 catalogue were Miss Cowley's Pocket Sphere (for teaching geography), and Alphabetical Cards for enticing Children to acquire an early Knowledge of their Letters. A dissected map of England, (a forerunner of modern Jigsaw puzzles) was also advertised by him between 1795 and 1801.

Retail bookselling

In 1787 the business opened a retail bookshop at 17 Queen Street, Cheapside (hitherto the Aldermary Churchyard premises had principally served as a wholesale supplier and printing office).[15] The shop seems to have closed about 1799 when the business appears to have suffered a financial setback following his break with Hannah More.

Children's periodicals

On four occasions during his career Marshall attempted to start periodicals for children. These were:

- The Juvenile magazine; or, An instructive and entertaining miscellany for youth of both sexes edited by Lucy Peacock, 1788.

- The Family magazine; or, a Repository of religious instruction, and rational amusement edited by Sarah Trimmer, 1788-9.

- The Children's magazine; or, Monthly repository of instruction and delight, 1799.

- The Picture magazine, or, monthly exhition for young people, 1800–1801.

Cheap Repository Tracts

Marshall was the London printer and publisher of Hannah More's Cheap Repository Tracts between 1795 and December 1797. Following a dispute with More in 1797 Marshall published his own series of Cheap Repository Tracts until 1799.[16] Following the formation of the Religious Tract Society in 1799 Marshall abandoned tract publishing and concentrated on new forms of publication for children.

Miniature libraries and Cabinets

Marshall published a range of attractive miniature libraries in wooden cases, after 1799, including "The Child's Latin Library", "The Doll's Library", "The Infant's Library", or "The Juvenile; or child's library".[17] Similarly, he published a range of "Cabinets" (wooden boxes containing sets of picture cards and miniature books) such as The Cabinet of Beasts, The Cabinet of Birds, The Cabinet of Fishes, The Infant's Alphabetical Cabinet, The Infant's Cabinet of the Cries of London or The Doll's Casket.

Picture Books

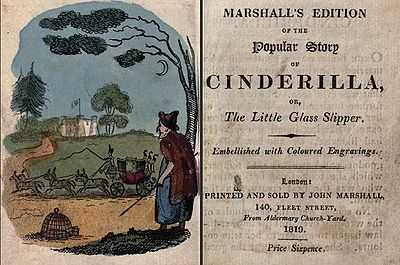

Marshall was an early innovator in the publication of coloured picture books for children, illustrated with hand-coloured etchings. During the early 19th century he published editions of many traditional fairy tales such as Cinderella, Puss in Boots or Aladdin, and accumulative rhymes and games such as 'The House that Jack built', 'The Barn that Tom built', or 'The Gaping Wide-mouth'd Waddling Frog', with hand-coloured illustrations.[18] He was also noteworthy for publishing a range of books of humorous verses illustrated by the caricaturist Isaac Robert Cruikshank.

Other activities

In common with other contemporary printers and publishers, John Marshall was involved in the sale of patent medicines, although in his case these were aimed specifically at children. He advertised 'an improved preparation of Dr. Waite’s Worm Medicine ... impossible to distinguish it from the most agreeable Gingerbread Nut', from premises at 44, Long-lane, West Smithfield, in 1793.[19]

He also appears to have been a supporter of the movement to abolish the slave trade in Britain. He printed a number of anti-slavery tracts as well as a print depicting "The cruel treatment of slaves in the West Indies", 1793.[20]

Children's literature

After the death of John Newbery, the first publisher to make a profit publishing children’s literature, many firms began to enter the business, but none ever had the monopoly Newbery did.[21] Marshall was one of the most successful and he published "the most original books", popularizing fictional biography for juvenile readers.[21] In general, Marshall published books that were more serious than Newbery’s, emphasizing the "instruction" part of "to instruct and delight", the imperative of 18th-century children’s literature. His catalogue included this announcement:

Ladies, Gentlemen, and the Heads of Schools, are requested to observe, that the beforementioned Publications are original,, and not compiled: as also, that they were written to suit the various Ages for which they are offered; but on a more liberal Plan, and in a different Style from the Generality of Works designed for young People: being entirely divested of that prejudicial Nonsense (to young Minds) the Tales of Hobgoblins, Witches, Fairies, Love, Gallantry, etc. with which such little Performances heretofore abounded.[22]

However, although Marshall advocated more disciplined stories, he also published Newbery-inspired stories that “stressed amusement” and would sell well, including fairy tales.[23] By the mid-1780s, he was focusing almost exclusively on moral works that had a strong Christian element. As Samuel Pickering, Jr., a scholar of 18th-century children’s literature, explains, “he was a shrewd publisher and, reading the market well, he saw that instruction would sell. While keeping a selection of old-fashioned, amusing books in print….he established a reputation as a printer of moral works.”[24] Mary Jackson describes his strategy in sharper terms, saying he engaged in "apparent duplicity and sharp tricks", claiming that he was a reforming publisher but issuing tales that had little moral redemption in the eyes of Trimmer, Fenn, Kilner, and others.[25] In 1795, he became a printer for Hannah More’s Cheap Repository Tracts.[24]

Marshall learned from Anna Laetitia Barbauld’s innovative children’s literature and began to use large fonts and margins; he also began to publish graduated readers like her Lessons for Children. Ellenor Fenn wrote a series for him which began with Cobwebs to Catch Flies.[26] He also recognized the value of illustrations in children’s books. Beginning in the mid-1780s, he and Sarah Trimmer published several sets of illustrated stories about the Bible and ancient history.[27]

In common with most contemporary commercial publishers Marshall was driven by profit and he paid his writers poorly. Mrs Fenn received no monetary payment for her works, merely printed copies of Marshall's works to give away as gifts to her friends and neighbours.[28] Mrs Trimmer's Description of a Set of Prints of Scripture History and Description of a Set of Prints of Ancient History, among others, went through many editions and no doubt made money for Marshall, but she did not see much of the profits. She complained that he treated her like "a mere bookseller's fag".[29] More described him as "selfish, tricking and disobliging from first to last" and resented his desire to make as much money as possible from the Cheap Repository Tracts. However, she saw their publication as a moral crusade, whereas he had grown up publishing such works as a business. When More took her publishing elsewhere, thereby seriously undermining Marshall's business, he responded by issuing his own series of tracts in competition.[30]

Like Newbery, Marshall’s authors advertised his books within their texts. For example, in Anecdotes of a Boarding School, a mother gives her daughter Marshall’s Dialogues and Letters and Adventures of a Pincushion as she is going off to school. In Jemima Placid, the heroine reads books that could "be bought at Mr. Marshall’s" and her father determines to buy many for his friends.[31]

External links

Notes

- ↑ Laws, Emma. "The Children’s Printer". Miniature Libraries. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 5 April 2007..

- ↑ Darton, p. 164.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Familysearch

- ↑ McKenzie, p. 140.

- ↑ Will – National Archives PROB 11/1688.

- ↑ National Archives PCC wills, PROB 11/1057, July 1779.

- ↑ London Gazette 30 March 1790, p. 201.

- ↑ The Times, 16 October 1806; p. 1.

- ↑ National Archives PROB 11/1688.

- ↑ O'Connell, 56–60, and Shephard, 25-9, Simmons.

- ↑ Darton, pp. 137-38 & 161-4.

- ↑ Pickering, p. 92.

- ↑ British Museum Dept of Prints and Drawings Heal, 17.97.

- ↑ Stoker, pp. 827–832.

- ↑ Pollard, p. 20.

- ↑ Spinney

- ↑ Alderson, 'Miniature libraries'

- ↑ Alderson and de Marez Oyens, pp. 135-8.

- ↑ The World, 11 November 1793.

- ↑ O'Connell, p. 57.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Pickering, p. 91.

- ↑ Quoted in Darnton, p. 161.

- ↑ Pickering, p. 177.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Pickering, p. 180.

- ↑ Jackson, pp. 124–126.

- ↑ Pickering, pp. 188, 192.

- ↑ Pickering, p. 188.

- ↑ Stoker, p. 836.

- ↑ Jackson, p. 122.

- ↑ Jackson, p. 124.

- ↑ Pickering, p. 229.

References

- Brian Alderson, "Miniature libraries for the young", The Private Library, 3rd series 6. (1983), 3–38.

- Brian Alderson and de Marez Oyens, Felix, Be merry and wise: origins of children’s book publishing in England 1650–1850, New York: The Pierpoint Morgan Library, 2006.

- Darton, F. J. Harvey. Children’s Books in England. 3rd ed. Rev. Brian Alderson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Jackson, Mary V. Engines of Instruction, Mischief, and Magic: Children’s Literature in England from Its Beginnings to 1839. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1989.

- Laws, Emma The Children’s Printer', Miniature Libraries, London: Victoria and Albert Museum http://www.vam.ac.uk/vastatic/wid/exhibits/miniaturelibraries/childrensprinter.html

- McKenzie, D. F. (ed.), Stationers’ company apprentices 1701–1800, Oxford Bibliographical Society, 1978.

- O'Connell, Sheila The popular print in England 1550–1850, London: British Museum, 1999.

- Pollard, Graham (ed.), The Earliest Directory of the Book Trade by John Pendred (1785), London: the Bibliographical Society, 1955.

- Pickering, Samuel F., Jr. John Locke and Children’s Books in Eighteenth-Century England. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

- Shepard, Leslie, John Pitts ballad printer of Seven Dials, London 1765–1844, London: Private Libraries Association, 1969.

- Simmons, R. C. (ed.), The Dicey-Marshall Catalogue http://www.diceyandmarshall.bham.ac.uk/.

- Spinney, G. H., "Cheap Repository Tracts; Hazard and Marshall edition", The Library, Vol. 20, Fourth Series, (1939–40), pp. 295–340.

- Stoker, David. "Ellenor Fenn as 'Mrs Teachwell' and 'Mrs Lovechild': a pioneer late eighteenth century children’s writer, educator and philanthropist". Princeton University Library Chronicle (2007). pp. 816–850.

|