John Knatchbull (Royal Navy captain)

John Knatchbull (c. 1791 – 13 February 1844) was a naval captain and convict found guilty of murder in 1844. He was one of the earliest to raise in a British court the plea of moral insanity (unsuccessfully).

Biography

Knatchbull was born in Mersham, Kent, England, probably the son of Sir Edward Knatchbull 8th Baronet of Mersham Hatch.[1]

He attended Winchester College and volunteered for the navy in 1804 serving until 1818 and rising to the rank of a captain. He served in the Ardent, Revenge, Zealand, Sybille, Téméraire, Leonidas, Cumberland, Ocean and Ajax. In November 1810 he passed his lieutenant's examination, served in Sheerwater until August 1812 when he was invalided home, and then in Benbow and Queen. In December 1813 he was commissioned to command Doterell, but missed the ship and was reappointed in September 1814. After the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815, the navy was reduced and Knatchbull retired on full pay until March 1818, when his pay was stopped by the Admiralty because of a debt he had incurred in the Azores.[1]

Transportation

In August 1824 he was found guilty of stealing with force and arms at the Surrey Assizes under the name of John Fitch. Knatchbull was given a 14 year sentence and transported to New South Wales on the Asia.[2]

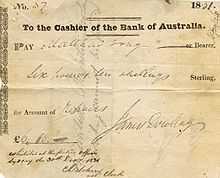

In New South Wales he was assigned to Bathurst. He was given a ticket of leave in 1829 after apprehending eight runaways.[3] His ticket was altered to Liverpool when he became an overseer on the Parramatta Road. On 31 December 1831 he was charged with forging Judge Dowling's signature to a cheque on the Bank of Australia; he was found guilty and sentenced to death in 1832. This sentence was commuted to transportation for seven years to Norfolk Island.[1]

While on Norfolk Island, he took part in two mutinies. En route to Norfolk Island in 1832 Knatchbull conspired with other convicts on board ship to poison the crews' and guards' food with arsenic.[4] The mutineers were informed on and the arsenic was found, but it was seen as too much trouble to return the prisoners to the mainland for trial and they became known among their fellow convicts as "Tea-Sweeteners".[5] In the second mutiny of 1834 planned against the governor of the convict settlement and his deputy, Knatchbull escaped punishment by informing on his fellow mutineers.[5]

While Knatchbull was on Norfolk Island, Thomas Atkins, an Independent clergyman who was sent to Norfolk Island as a Chaplain in November 1836 on the recommendation of the London Missionary Society, said of Knatchbull

from his personal appearance and conversation, as all traces of a gentleman had long disappeared, he exhibited no evidence that he had been in a higher social position; indeed he appeared to be in his natural place.[6]

Knatchbull returned to Sydney in 1839 to serve out the remainder of his original sentence (the 14 years for stealing with force and arms).[2]

Murder of Ellen Jamieson and death

In January 1844 he murdered shopkeeper Ellen Jamieson with a tomahawk while stealing money for his upcoming marriage. He was tried on 24 January and found guilty of murder and sentenced to be hanged.[2]

During the early part of 1844, two murders of a very horrible character were committed in Sydney. In one case, a Norfolk Island expiree, who held a ticket of leave, had gone into the shop of a poor widow, named Ellen Jamieson, and asked for some trifling article. While Mrs. Jamieson was serving him, the ruffian raised a tomahawk, which he held in his hand, and clove the unfortunate woman's head in a savage manner. She lingered for a few days, and died, leaving two orphan children. The murderer, whose name was John Knatchbull, was proved to have been a wretch of the most abominable description; and though an attempt was made to set up a plea of insanity, a barrister being employed by the agent for the suppression of capital punishment, so foul a villain could not be saved from the gallows. It is gratifying to add, that Sir Edward Knatchbull, the brother of the criminal, has sent out a handsome donation for the orphans of Mrs. Jamieson.[7]

Knatchbull's defence was conducted by Robert Lowe, 1st Viscount Sherbrooke. Lowe argued on Knatchbull's behalf that insanity of the will could exist apart from insanity of the intellect. He argued that Knatchbull had yielded to an irresistible impulse and could not be held responsible for his crime. This was a novel defence for the time. The court, however, found Knatchbull guilty. The Lowes subsequently adopted the murdered woman's two young children, Bobby and Polly Jamieson.[8] Knatchbull's brother provided money for the children's education.[4][7]

Knatchbull appealed unsuccessfully on the grounds that the judge had not directed that his body be dissected and anatomized, as required by law.[1] His hanging on 13 February 1844 occurred in Taylor Square and was witnessed by 10,000.[9][10]

John Knatchbull sentenced to hang for the murder of Ellen Jamieson: The execution to be held outside the gates of the three-year-old [Darlinghurst] gaol, was scheduled for 9a.m. At the crack of dawn scores of people, children included, were swarming across the racecourse (Hyde Park) towards Darlinghurst Hill. The Australian newspaper judged the throng to be 10,000 strong. The paper was disdainful of the ghoulish mob yet, at the same time, congratulated them on their good behavior. Captain John Knatchbull aged 56 years, was led out into Forbes Street, at the gaol gates on the Darlinghurst Ridge. Wearing genteel black broadcloth, Captain Knatchbull then "ascended the fatal scaffold without trepidation or fear, and was launched into another world with a noble and fervent prayer trembling on his lips". The bell of St Phillip's tolled thrice and John Knatchbull was dead.[11]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Knatchbull, John (1792? - 1844)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. 1967. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Convict records". Archives. State Records Authority of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ "image of Knatchbull's ticket of leave". State Records of NSW. Archived from the original on 2008-01-17. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 West, John. The History of Tasmania - Volume II (of 2). Launceston, Tasmania: Henry Dowling. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bennett, Bruce (2006). "In the shadows: the spy in Australian literary and cultural history". Goliath reproducing an article from Antipodes. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ Sargent, Clem (2005). "The British Garrison in Australia 1788-1841: the mutiny of the 80th regiment at Norfolk Island". Goliath reproducing an article from Sabretache. Retrieved 2008-03-13. citing Reverend Thomas Atkins, 1869, Reminiscences of Twelve Years' Residence in Tasmania and New South Wales, Malvern, England, p. 57 and also Colin Roderick, 1963, John Knatchbull from Quarterdeck to Gallows, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, pp. 156-240

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Braim, Thomas Henry (2005) [1846]. A History of New South, Wales: From Its Settlement to the Close of the Year 1844. Google books. pp. pages 95–6. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ Knight, R. L. (1967). "Lowe, Robert [Viscount Sherbrooke] (1811 - 1892)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- ↑ Norrie, Philip Anthony (2007). "An Analysis of the Causes of Death in Darlinghurst Gaol 1867-1914 and the Fate of the Homeless in Nineteenth Century Sydney" (pdf of 187 pages). Thesis for Master of Arts (Research). University of Sydney. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

page 103: The most famous public hanging at the goal was that of aristocrat John Knatchbull at 7 a.m. on Tuesday 13 February 1844. He was executed for murdering Ellen Jamieson and a crowd of over 10,000 witnessed his death. The last public hanging occurred on 21 September 1852, when murderer, Thomas Green, was dispatched.

- ↑ Pelly, John (31 January 2005). "History in the dock". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

These public events continued until John Knatchbull - found guilty of murder after the court rejected the colony's first recorded insanity plea - met his fate in Taylor Square in February 1844. The newspapers offered disapproving words about the number of women and children in the crowd of 10,000.

- ↑ "Darlinghurst Gaol". darlinghurst.biz. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-07.