John Fraser (botanist)

| John Fraser FLS, F.R.H.S. | |

|---|---|

.png) John Fraser (lithograph of an 18th-century portrait) | |

| Born | 14 October 1750 |

| Died | 26 April 1811 (aged 60) |

| Occupation | Botanist and plant collector |

| Years active | 1780–1810 |

| Known for | Discovery and introduction of the flora of the Americas to Europe |

John Fraser, FLS, F.R.H.S.,[1] (14 October 1750 – 26 April 1811) was a Scottish botanist who collected plant specimens around the world, from North America and the West Indies to Russia and points between, with his primary career activity from 1780 to 1810.[2][3][4] Fraser was a commissioned plant collector for Catherine, Czar of Russia in 1795, Paul I of Russia in 1798,[5] and for the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna in 1806;[6] he issued nursery catalogues c. 1790 and 1796,[7] and had an important herbarium that was eventually sold to the Linnean Society.[3][8][9]

Family and early life

Family

Fraser was born during the Age of Enlightenment at Tomnacross, the Aird, Inverness-shire on 14 October 1750. His father was Donald Fraser, (a.k.a. Donald Down, a patronymic descriptive of hair color traditional amongst the Scots Highlanders); his mother was Mary McLean, and his siblings included a brother James (b. 16 March 1753) and sister Christiana (b. 5 December 1756).[9] Fraser's eldest son John Jr. (c. 1779–1852) continued in his father's footsteps as a plant hunter after Fraser's death[3] and became a respected nurseryman in his own right (ALS 1848).[10] John Jr. also owned the Hermitage Nursery at Ramsgate (1817–1835) and when he retired he sold his nursery to William Curtis in 1835.[9] John Jr. met with the celebrated American botanist Asa Gray in 1839, early on in Gray's career, and ultimately sold the Fraser herbarium to the Linnean Society in 1849.[9] Fraser's younger son James Thomas directed the family nursery at Chelsea with his older brother until 1811 and then on his own until 1827.[10] Fraser's grandson John became a member of the Royal Horticultural Society, attending meetings in 1877.[5]

Early life

In 1770, five years before the American War of Independence and coincident with Captain James Cook's discovery of the eastern Australian coast, Fraser arrived in London as a young man to make his way in the city, at first following the trade of a hosier (a draper working with linen).[5] He soon came to know the Chelsea Physic Garden, and it was through his visits there that he became inspired with a desire to advance horticulture in England.[5] He married Frances Shaw on 21 June 1778 and settled down in a small shop in Paradise Bow, Chelsea.[9]

Starting out

.jpg)

Not long content with life in London, Fraser soon began to quit the mercantile counter as often as he could to watch the gardeners at work.[5] He befriended William Forsyth who at that time had charge of the Apothecaries' Garden;[5] through that acquaintance he would have become familiar with his predecessor Mark Catesby's travels, as some of Catesby's specimens from his travels were housed at the Chelsea Physic Garden, and Catesby's writings and engravings on the flora of the Americas were also published by the time Fraser moved to London.

Fraser took up botanical collecting and, two years after the United States of America had named itself, departed England for Newfoundland in 1780 with Admiral Campbell.[6] Upon returning to England, he sailed again in 1783 to explore the New World with his eldest son John Jr.[5] Fraser's early expeditions were financed by William Aiton of Kew Gardens, William Forsyth, and James Edward Smith of the Linnean Society.[11] In the 1780s Fraser established the American Nursery at Sloane Square, King's Road, which his sons continued after his death in partnership from 1811–1817.[3] The nursery was on the east side of the Royal Military School and extended over twelve acres.[3]

Travels

As the 18th century came to a close, botanists who hunted plants afar were adventurers and explorers, John Fraser among them, fielding shipwrecks, sieges, slavery, pirates, escaped convicts and hostile natives.[12] Fraser travelled extensively, from Scotland to England, the Americas, the West Indies, Russia, and points between. He began by collecting in Newfoundland from 1780 to 1783 or 1784,[13] and then moved on to the Appalachian Mountains in eastern North America,[2] all without the benefit of railroads or well-established highways. By the time he completed his journeys, John Fraser had introduced about 220 distinct species of plants from the Americas to Europe and beyond.[6]

Appalachia and the Alleghenies

Fraser made his first trip to the American south, and specifically to Charleston, South Carolina in 1783 or 1784,[14] sending home consignments of plants to a Frank Thorburn of Old Brompton. Returning to England in 1785 with the expectation of recompense for his labour and risk, he was astonished to learn that all the valuable plants he had forwarded were dead, and the survivors, which were common, could not be disposed of.[5] Vexed, Fraser subsequently entered into a lawsuit over the matter, a suit long and very expensive to both parties,[14] but sailed again for South Carolina in the autumn nonetheless.[5]

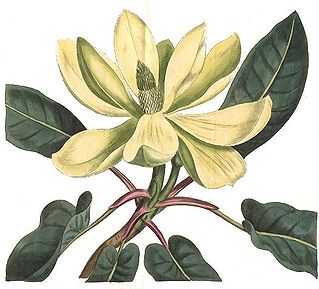

On his return trip that autumn he made his way north through Berkeley County to the Santee River, befriending Thomas Walter along the way.[15] He continued on to the Piedmont region of the Appalachians, discovering Phlox stolonifera (Creeping Phlox) in Georgia along the southeastern edge of the southern Blue Ridge,[16] and in 1787 arrived in Pickens County near Cherokee land during the Chickamauga Wars. There he collected what became known later as Magnolia fraseri.[15] Fraser gave his contemporary William Bartram his original specimen of Magnolia fraseri; the specimen is housed in the Walter Herbarium in the British Museum of Natural History collection.[15] The Hortus Kewensis recorded 16 new plants as having been introduced by Fraser in 1786, and five more in 1787.[14]

| “ | One of the most enterprising, indefatigable, and persevering men that ever embarked in the cause of botany and natural science. | ” |

| —J. C. Loudon, | ||

Fraser trekked the Allegheny Mountains in 1789 when trans-Allegheny travel was limited to indigenous peoples' trails and one military trail, Braddock Road, built in 1751 and too far north of his journeys to be of help. He travelled with François André Michaux, and on the summit of the Great Roan was the first European to discover the Rhododendron catawbiense, now cultivated in many varieties.[2] Of the rhododendrons he wrote "We supplied ourselves with living plants, which were transmitted to England, all of which grew, and were sold for five guineas each."[6]

Charleston nursery

John's brother James was actively involved with the American side of Fraser's plant export-import business, and from at least 1791 they jointly leased some land in Charleston until May 1800. In 1796, the brothers additionally mortgaged 406 acres on Johns Island along the marshy edge of Stono River, originally a part of the Fenwick Hall estate.[9] The brothers had difficulties with their land deals though, and in 1798 they fell behind in their payment obligations to the extent that their creditors instituted litigation to collect past due sums.[9] Despite their problems with lawsuits, leases, mortgages, and land too marshy to be perfectly suited to their enterprise, in 1810, the year prior to Fraser's death, large numbers of rhododendrons, magnolias, and other native plants were still being shipped from the Fraser brothers' Charleston nursery by their agents there.[9]

Russia and shipwreck

In 1795 Fraser made a first visit to Saint Petersburg where he sold a choice collection of plants to the Empress Catherine;[5] to his delight she requested he set his own price.[6] While there, he bought Black and White Tartarian cherries in 1796, thereafter introducing them for the first time to England.[6] In 1797 Czar Paul I ordered that Fraser be paid 4,000 rubles for his plants that year, and by the next spring, Fraser had received £500 sterling for his efforts.[9] In 1798 Fraser travelled again to Russia, returning afterward with the commission Botanical Collector to the Emperor Paul,[5] under the signature of each Paul and Catherine and dated Pavlovskoe, August, 1798.[14]

Based on his trust in the Imperial commission[9] and in furtherance of carrying out the duties it imposed upon him,[14] Fraser and his eldest son John started out once more in 1799, bound for America and the West Indies.[2] They visited with Thomas Jefferson at Monticello and made an extended journey through Kentucky, eastern Tennessee, and northern Georgia, returning to Charleston in December 1800.[9] From there they set out for Cuba, but the sailing was a perilous one since between Havana and the United States they were shipwrecked on a coral reef, about 40 miles (64 km) from land and 80 miles (130 km) from Havana,[6] escaping only with great difficulty.[5] "For six days they, with sixteen of the crew, endured the greatest privations until picked up by a Spanish boat and conveyed to land."[6] The trip was nearly disastrous and the men barely escaped with their lives.[9]

Cuba

While collecting specimens in Cuba, "a time when the sea [was] swarming with pirates",[17] Fraser met the explorers Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland on their circuitous journey from the Amazon to Cartagena.[3] John's son returned to England first, transporting a large botanical collection of Humboldt's after he had kindly intervened on their behalf during their sojourn to keep them safe.[9] Fraser returned from Cuba to America and then to England in 1801 or 1802 with "a goodly collection of rarities,"[5][18] one of which was his discovery (as a European) of Jatropha pandurifolia.[10] In 1807, both father and son again sailed for North America and the West Indies.[2] On his next trip to London after collecting in Matanzas, Fraser brought home a tropical palm with silvered leaves, Corypha miraguama,[19] and made a manufacturing proposal for hand-weaving of hats and bonnets from its leaves; Fraser's sister Christiana "Christy" Fraser, opened an establishment for the purpose under the Queen's patronage (the Queen herself was an amateur botanist) and employed a number of people,[14] but the scheme ultimately failed, possibly through scarcity of material.[5][9]

Business difficulties

When Fraser made his next visit to the Romanov court in 1805 expecting remuneration, to his great disappointment he discovered that the new Emperor would have nothing to do with him.[5][9] Undaunted, he repeated the trip, visiting both Moscow and Saint Petersburg, but in vain.[5] After the Emperor Paul I's assassination in March, 1801, the new Emperor Alexander I declined to recognise Fraser's appointment. Fraser petitioned his cause for two years, finally resorting to seeking assistance from the British ambassadorial corps, and was ultimately paid 6,000 rubles by royal decree in April, 1803.[9] The Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, an enthusiastic amateur botanist herself, supported his efforts, giving him a diamond ring and commissioning him for specimens for the Imperial Gardens of Gatchina and Pavlovsk Palace.[6] The director of the Imperial Botanic Garden at Saint Petersburg catalogued 18 of Fraser's North American species in the early years of the 19th century, with some of the specimens surviving as of 1997 in the Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences.[9]

After the Romanov affair, Fraser faced severe financial difficulty, though again he sailed to America.[9] While successful in his researches there, his nursery at home fell into neglect through his absence and money problems.[5] His financial situation may have affected his relationship with his brother James, since in 1809 Fraser sued his brother as former business partner in the Charleston Court of Common Pleas for debts exceeding £1,042.[20]

Later voyages

Fraser made his seventh and last voyage to the United States in 1807. Near Charleston he fell from his horse and broke several of his ribs, an injury from which he never fully recovered.[6] His final voyage before returning to England was from America to Cuba in 1810 for a last visit to a country that welcomed him despite the nationalistic differences of the day, and from which he had a richly rewarding collecting history.[6]

Death

Although he was known to his contemporaries as "John Fraser, the indefatigable",[13] owing to his business and travel vexations and possibly also to exhaustion from his injuries after his fall, and his frequent and fatiguing journeys, his life was shortened — though a robust man, he died in April, 1811 in London, Sloane Square,[21] at only 60, leaving two sons;[5] his wife died a few years afterwards.[10] He did live long enough to see one grandchild, William, born to John Jr. and his wife Sarah on 30 June 1808, and more offspring came later from both his sons.[9] Fraser's financial difficulties must have been a heavy burden to his family even after he died, since two years afterward he was declared to have been bankrupt at his death.[9] Fraser did take care of his family though, as the terms of his will gave his unmarried sister Christy a place in his home and financial aid from his sons; in 1818 Christy was still receiving her support as specified by that will.[9]

Legacy

Throughout his travels, Fraser sent his collections to his nursery in London for reproduction and general sale to gardeners and architects coming to London to look for plants; to his herbarium (later becoming that of the Linnean Society) for further study; and to his clients, including Catherine the Great, the Emperor Paul I, the Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna, the Chelsea Physic Garden, William Aiton (head gardener of Kew Gardens), Sir James Edward Smith (founder of the Linnean Society), and others.[22] William Roscoe wrote of him: "John Fraser brought more plants into this kingdom [Britain] than any other person."[23]

Though Fraser died young, his sons carried on their father's work; John Jr. returned to America where he continued his own botanic excursions until 1817 before returning to England and founding his own nursery.[2] Fraser was hailed early on by his biographers as "[O]ne of the most enterprising, indefatigable, and persevering men that ever embarked in the cause of botany and natural science."[14]

Family tree

- Donald Fraser & Mary McLean[24]

- John Fraser & Frances Shaw

- John Fraser Jr. & Sarah

- William

- John

- James

- James Thomas & Margaret

- John Francis

- Robert Charles

- Edmund William

- John Fraser Jr. & Sarah

- James Fraser & Elizabeth Martin

- Elizabeth

- Michael

- Thomas Martin

- John Martin

- Christiana "Christy" Fraser

- John Fraser & Frances Shaw

Species named for Fraser

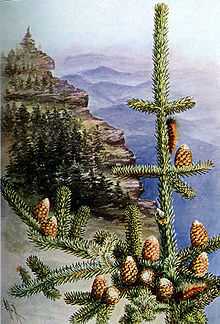

Species named after Fraser include, among others, Abies fraseri (Fraser Fir), Magnolia fraseri (Fraser Magnolia), and the gentianworts, Frasera.[1] A 50-foot Fraser Fir was used in 1998 as the U.S. Capitol Christmas Tree; the species was also used in 1974.[25]

Publications

- Fraser, John, pub., Thomas Walter, Flora Caroliniana, 1788.

- Fraser, John, A Short History of Agrostis Cornucopiae, 1789.

- Fraser, John, Nursery Catalogues, repub. in Journal of Botany, British and Foreign, vol. 37, 1899, pp. 481–87.[26]

- Fraser, John, Nursery Catalogues, repub. in Journal of Botany, British and Foreign, vol. 45, 1907, p. 255; and vol. 53, 1915, p. 271.

- Fraser, John, Nursery Catalogues, repub. in Journal of Botany, 1921, pp. 69–71.[3]

Letters and portraits

John Fraser's letters are maintained at the Royal Society of Arts, and one of his portraits hung at the Hunt Library.[3] Both Hoppner and Raeburn painted his portrait.[22] Fraser was an elected fellow of both the Linnean Society of London (FLS 1810)[3] and the Royal Horticultural Society, denoted by his use of "F.R.H.S.".

Botanical name notes

John Fraser's son John Jr., né John Fraser (c. 1779–1852), takes the author abbreviation Fraser f. in citations.

North American plants discovered and introduced

by John Fraser between 1785 and 1799; and by J. Fraser, Jr., from 1799 to 1817.[28]

- Agrostis Cornucopiae.

- Aletris aurea.

- Allium cernuum, Bot. 1324.

- — reticulatum.

- Andromeda cassinaefolia, Bot. Mag. t. 970.

- — Catesbaei, Bot. Mag. t. 1955.

- — dealbata, Bot. Reg. t. 1010.

- — ferruginea.

- — floribunda, Bot. Reg. t. 1566.

- — serratifolia.

- Annona pygmaea.

- Asarum arifolium. Hook Ex. Fl. t. 40.

- Asclepias amplexicaulis.

- — acuminata.

- — Linaria.

- — pedicellata.

- — perfoliata.

- — salviaefolia.

- Azalea arborescens.

- — calendulacea, Bot. Mag. t. 1721(β)

- — canescens.

- — coccinea, Bot. Mag. t 180.

- — glauca.

- — nitida.

- Bartsia coccinea.

- Befaria racemosa.

- Betula lutea.

- Blandfordia cordata.

- Buchnera pedunculata.

- Calycanthus glaucus, Bot. Reg. t. 404.

- — laevigatus, Bot. Reg. t. 481.

- Carex Fraseriana, Bot. Mag. t. 1391.

- Chaptalia tomentosa, Bot. Mag. (Tussilago integrifolia) t. 2257.

- Clethra scabra.

- Collinsonia ovalis.

- — tuberosa.

- Commelina angustifolia.

- Convolvulus tenellus.

- Coreopsis latifolia.

- Corypha Hystrix.

- Cristaria coccinea, Bot. Mag. t. 1673.

- Croton maritimum.

- Cypripedium Calceolus.[29]

- Cypripedium pubescens, Lodd. t. 895.

- Cypripedium reginae.[30]

- Cyrilla Caroliniana, Bot. Mag. t. 2456.

- Diospyros pubescens.

- Dracocephalum caeruleum.

- Echites difformis.

- Elaeagnus argenteus.

- Erigeron bellidifolium.

- — compositum.

- — nudicaule.

- Euphorbia Ipecacuanha, Bot. Mag. t. 1494.

- — marginata.

- Frasera Walteri.

- Galardia bicolor, Bot. Mag. t. 1602, and vars. 2940, and 3368.

- Gentiana crinita, Bot. Mag. t. 1039 (G. fimbriata).

- — incarnata, Bot. Mag. t. 1856.

- Gerardia flava.

- — quercifolia.

- — tenuifolia.

- Gnaphalium undulatum.

- Halesia parviflora.

- Hamamelis macrophylla.

- Helonias angustifolia, Bot. Mag, t. 1540.

- Hydrangea quercifolia, Bot. Mag. t. 975.

- — radiata.

- Hypoxis juncea.

- Ilex angustifolia.

- Illicium parviflorum.

- Ipomaea Jalapa, Bot. Mag. t. 1572.

- — Michauxii.

- — sagittifolia.

- Ipomopsis elegans, Bot. Reg. t. 1281.

- Jeffersonia diphylla, Bot. Mag. t. 1513.

- Juglans amara.

- — porcina.

- — sulcata.

- Kalmia hirsuta, Bot. Mag. t. 138.

- — rosmarinifolia.

- Larix Fraseri.

- Laurus Caroliniensis

- — Catesbaei.

- — Diospyros, Bot. Mag. t. 1470.

- — melissaefolia, Bot. Mag. t. 1470.

- Liatris cylindracea

- — elegans.

- — odoratissima.

- — pilosa.

- — sphaeroidea.

- Lilium Catesbei Bot. Mag. t. 259.

- Lobelia puberula, Bot. Mag. t. 3292.

- Lonicera Caroliniensis.

- — flava, Bot. Mag. t. 1318.

- Lupinus villosus.

- Macbridea pulchra.

- Magnolia auriculata, Bot. Mag. t. 1206.

- — Fraseri.

- — cordata, Bot. Reg. t. 325.

- — macrophylla, Bot. Mag. t. 2189.

- — pyramidata, Bot. Reg. t. 407.

- Malachodendron ovatum, Bot. Reg. t. 1104.

- Malaxis unifolia.

- Menziesia ferruginea, Bot. Mag. t. 1571.

- — globularis.

- Mespilus spathulata.

- Muhlenbergia diffusa.

- Nelumbium macrophyllum.

- Neottia cernua, Bot. Mag. t. 1568.

- — tortilis.

- Nymphsea odorata, Bot. Mag. t. 819.

- — reniformis.

- Œnothera caespitosa, Bot. Mag. t. 1593.

- — Fraseri, Bot. Mag. t 1674.

- — glauca, Bot. Mag. t. 1606.

- — macrocarpa, Bot. Mag. t. 1592.

- — Missourensis.

- Orchis spectabilis, Exot. Fl. t. 69.

- Pachysandra procumbens, Bot. Mag. t. 1964.

- Pancratium Carolinianum, Bot. Reg. t. 926.

- Pavia macrostachya.

- Pedicularis Canadensis, Bot. Mag. t. 2506.

- Phalangium esculentum, Bot. Mag. t. l574.

- — (Quamash).

- Pinckneya pubescens.

- Pinguicula lutea, Bot. Reg. t. 126.

- Pinus Cedrus.[30]

- Pinus lutea.

- — palustris.

- — pungens.

- Phlox acuminata, Bot. Mag. t 1880.

- — amaena Bot. Mag. t. 1308.

- — Carolina, Bot. Mag. t. 1344.

- — nivea.

- — pyramidalis.

- — setacea, Bot. Mag. t. 415.

- — stolonifera, Bot. Mag. t. 563.

- — subulata, Bot. Mag. 411.

- Polygonum arifolium.

- Pontederia lanceolata.

- Prunus Chicasa.

- — maritima.

- Prunus pygmaea.

- Pycnanthemum lanceolatum.

- — verticillatum.

- Pyrola maculata, Bot. Mag. t. 897.

- — repens.

- Pyxidanthera barbulata.

- Quercus Bannisteri.

- — Catesbaei.

- — castanea.

- — hemisphaerica.

- — imbricaria.

- — laurifolia.

- — lyrata.

- — Michauxii.

- — montana.

- — olivaeformis.

- — prinoides.

- — tinctoria.

- Rhexia Caroliniensis

- Rhododendron Catawbiense, Bot. Mag. t. 1671.

- — punctatum, Bot. Reg. 37.

- Ribes aureum, Bot. Reg. t. 125.

- — hirtellum.

- — resinosum, Bot. Mag. t. 1583.

- Rosa Caroliniensis.

- — laevigata.

- Rudbeckia pinnata, Bot. Mag. t. 2310.

- Sagittaria falcata.

- — graminea.

- — latifolia.

- Salix cordifolia.

- — falcata.

- Salvia azurea, Bot. Mag. t. 1728.

- Sarracenia adunca, Bot. Mag. t. 1710.

- — rubra, Bot. Mag. t. 3515.

- Satyrium repens.

- Schizandra coccinea, Bot. Mag. t. 1413.

- Scutellaria Canadensis.

- Sideranthus pinnatifidus.

- — villosus.

- Silene Pennsylvanica, Bot. Mag. t. 3342.

- — Virginica.

- Smilax lanceolata.

- — pubera.

- — quadrangularis.

- Streptopus roseus.

- Thalia dealbata, Bot. Mag. t. 1690.

- Thymbra Caroliniana, Bot. Mag. t. 997.

- Tradescantia rosea.

- Trillium pictum.

- — pusillum.

- Vaccinium buxifolium, Bot. Mag. t. 928.

- — frondosum.

- — myrsinites, Bot. Mag. t. 1550.

- — myrtifolium.

- — nitidum, Bot. Mag. t. 1550.

- — parviflorum, Bot. Mag. t. 1288.

- Verbena bracteosa, Bot. Mag. t. 2910.

- — rugosa.

- Viola papilionacea.

- — pedata, Bot. Mag. t. 89.

- — pubescens.

- — rotundifolia.

- Virgilia lutea.

- Ulmus alata.

- Uniola paniculata.

- Uvularia grandiflora, Bot. Mag. t. 1112.

- Waltheria Caroliniana.

- Xyris Canadensis.

- Yucca Missourensis.

- — recurva.

- — serrulata.

- Zamia pumila.

See also

- History of botany

- List of gardener-botanist explorers of the Enlightenment

- Scottish Enlightenment

- The Plant List

- International Plant Names Index

- Botanical name

- History of plant systematics

- History of taxonomy

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Johnson, George William, Johnson's Gardeners' dictionary and cultural instructor, London, A. T. De La Mare printing and publishing co., Ltd., 1916, title page and p. 361. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.20764. Accessed 31 July 2012. See also:

Card, H.H., A revision of Genus Frasera, Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, April 1931, 18(2):245–282 at 245. Accessed 2 August 2012. - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Brendel, Frederick, Historical Sketch of the Science of Botany in North America from 1635 to 1840, The American Naturalist, 13:12 (Dec. 1879), pp. 754–771, The University of Chicago Press. Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Desmond, Ray (ed.), Dictionary of British and Irish Botanists and Horticulturalists, CRC Press, 1994, p. 263. ISBN 978-0-85066-843-8. (Google book.) Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Faulkner, Thomas, John Fraser Obituary in An historical and topographical description of Chelsea, and its environs, v. 2, 1829, p. 41, (Google book). Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 5.10 5.11 5.12 5.13 5.14 5.15 5.16 5.17 The Old Market Gardens and Nurseries of London — No. 10, (52 MB file from archive.org) Journal of Horticulture, Cottage Gardner v. 57, 29 March 1877, pp. 112, 238, et al.. Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 Hogg, Robert, Life of John Fraser, Cottage Gardener, v. 8, 1851–2, pp. 250–252, as republished by Fraser, Don, John Fraser, short biography at the Wayback Machine (archived October 22, 2007), web page by the descendants of John Fraser, last update 21 September 2007. Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Desmond. (The catalogues were reprinted in the Journal of Botany in 1899, pp. 481–87; 1905, pp. 329–31)

- ↑ Ward, Daniel B., The Thomas Walter Herbarium Is Not the Herbarium of Thomas Walter, Taxon, 56(3):917–926, August 2007, at 917. Accessed 31 July 2012. The article attributes what was once thought of as Walter's herbarium to John Fraser.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 Simpson, Marcus B. Jr, Moran, Stephen W., and Simpson, Sallie, Biographical notes on John Fraser (1750–1811): plant nurseryman, explorer, and royal botanical collector to the Czar of Russia, Archives of Natural History, v. 24, pp. 1–18, ISSN 0260-9541. doi:10.3366/anh.1997.24.1.1, (fee-walled).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Fraser, Don, John Fraser, main page at the Wayback Machine (archived October 22, 2007), website by the descendants of John Fraser, last update 22 October 2007. Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ British Museum, Fraser, John (1750–1811), Database of Plant Collectors, plants.jstor.org. Accessed 5 August 2012

- ↑ Explorers, Hunter Biographies at the Wayback Machine (archived June 21, 2009), Scottish Plant Hunters Garden, pitlochry.org.uk, 21 June 2009. Accessed 4 August 2012.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Ward, Daniel B., Thomas Walter Typification Project, I. Observations On The John Fraser Folio, J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas (formerly SIDA, Contributions to Botany ("SCB")) 22(2):1111–1118, 2006. Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Loudon, J.C., Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum, (53 MB file from archive.org), v. 1, 2nd ed., 1854, London, Henry G. Bohn, pp. 119–22, at 120. Accessed 31 July 2102. Full text and other formats available at archive.org.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Rembert, David H. Jr., The Botanical Explorations of William Bartram, bartramtrail.org, 22 February 2012 (last update). Accessed 31 July 2012.

- ↑ Curtis's Botanical Magazine, 1802, t.1, p. 563, botanicus.org. Accessed 31 July 2102. "We are informed by Mr. JOHN FRASER, of Sloane-Square, Chelsea, that he first discovered this plant in Georgia, in the year 1786, together with PHLOX pilosa, setacea, and subulata, but that living plants were not brought to Europe till 1801, his fifth voyage to North-America, on botanical researches, in company with his son. This last voyage was undertaken in consequence of an ukase of their late imperial Majesties the Emperor and Empress of all the Russias, appointing him their Botanical Collector. We trust that so much zeal will meet with a due reward."

- ↑ Letter from Humboldt to Willdenow, Havana, February 21, 1801. Lettres américaines, éd. Hamy, pp. 107–109.

- ↑ Brendel and the Journal of Horticulture (1877) differ as to whether the return trip was made in 1801 or 1802; they also differ on the birthdate of his son John. Several of the references differ as to where John Fraser died, and whether he was 60 or 61 at his death.

- ↑ Humboldt et Bonpland, Corypha miraguama, Nov. Gen., 1816, 1, p. 298. Accessed 4 August 2012.

- ↑ John Fraser vs James Fraser, Case 52-A, Charleston County Court of Common Pleas (now the Ninth Circuit, South Carolina Circuit Court), Judgement Rolls, 1810, South Carolina Dept. of Archives and History, Columbia, S.C.; noted by Simpson, et al., p. 5.

- ↑ Or he died in Glasgow — the family account of his death place (and the Hogg article) differs from the accounts published in Brendel and Ward.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, Academic Press, biodiversitylibrary.org, 1906–9, p. 15. Accessed 31 July 2012. The text indicates "Sir George Raeburn" rather than Sir Henry Raeburn as portraitist, likely a scrivener's error as there was no knighted "George Raeburn" of the era. Additionally, both Hoppner and Raeburn are represented in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de La Habana, (museum site page), and Sir Henry Raeburn's studio was on George Street. Also, the article Art of the Moment, Black and White Magazine, newspaperarchive.com, 18 January 1908, p. 16, (requires Flash plugin) shows two portraits of Fraser, one by Hoppner and the other by Sir Henry Raeburn, and both are entitled as such.

- ↑ Simpson, et al., p. 9, citing Smith, P., Memoir and Correspondence of the late Sir James Edward Smith, M.D. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman, 2 vols., 1832, 1:122; citing: Letter from William Roscoe to James Edward Smith, 15 April 1820.

- ↑ Simpson, et al., pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Architect of the Capitol, 1998 Capitol Christmas Tree, aoc.gov. Accessed 31 July 2102.

- ↑ Britten, James, Fraser's Catalogues, Journal of Botany, British and foreign, biodiversitylibrary.org, vol. 37, 1899, pp. 481–87. Accessed 31 July 2102.

- ↑ "Author Query for 'Fraser'". International Plant Names Index.

- ↑ Hooker, William J., Biographical Sketch of John Fraser, Companion to the Botanical Magazine, biodiversitylibrary.org, v. 2, 1837, pp. 300–305. Accessed 4 August 2012. The bulk of the species list is from this work, except where otherwise annotated.

- ↑ Ward, Daniel B., Beckner, John, Thomas Walters Orchids, brit.org, Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 5(1), 2011, pp.205–211 at 209. Accessed 2012-8-6.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Ward, Daniel B., Thomas Walter's species of Hedysarum (Leguminosae), brit.org, Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, 4(2), 2010, pp.705–710 at 706. Accessed 2012-8-6.

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Further reading

-

Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1889). "Fraser, John (1750-1811)". Dictionary of National Biography 20. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 213–14.

Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1889). "Fraser, John (1750-1811)". Dictionary of National Biography 20. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 213–14. - Gentleman's Magazine, J. Nichols and Son, London, 1811, i596.

- Transactions of the Inverness Scientific Society and Field Club, Robert Carruthers & Sons, v. 8, 1912–18, pp. 416–17. Accessed 4 August 2012. (Servers sometimes down on the weekend.)

- Charters, Michael L., A Dictionary of Botanical and Biographical Etymology, California Plant Names: Latin and Greek Meanings and Derivations, calflora.net, 13 August 2009. Accessed 4 August 2012.

- Coats, Alice M., Quest for Plants, 1969, pp. 281–85. ISBN 978-0-289-27985-4.

- Gilmour, Ronald W., Foundations of Southeastern Botany: An Annotated Bibliography of Southeastern American Botanical Explorers Prior to 1824, Castanea, 68(sp1):5–142, 2002. doi:10.2179/0008-7475(2002)sp1[5:FOSBAA]2.0.CO;2. (fee-walled)

- Hadfield, Miles, et al., British Gardeners, Conde Nast, 1980, p. 127. ISBN 978-0-302-00541-5.

- Henrey, B., British botanical and horticultural literature before 1800, Oxford Univ. Press, v. 2, 1975, pp. 174, 382–85. ISBN 978-0-19-211548-5.

- Lasègue, A., Musée botanique de B Delessert, (Botanical Museum of Benjamin Delessert), Paris, 1845, pp. 199–200.

- Miller, Taxon, v. 19, 1970, p. 523. ISSN 0040-0262.

- Small, J.K., Thomas Walter's botanical garden, Journal of the New York Botanical Garden, v. 36, 1935, pp. 166–167.

- Stafleu, F.A., and Cowan, R.S., John Fraser, Taxonomic Literature, biodiversity.org, v. 1, 1976, p. 873. Accessed 4 August 2012.

- Urban, Ignatius (ed.), Symbolae Antillanae, seu, Fundamenta florae Indiae Occidentalis, (in German), v. 3, 1902, pp. 48–49. Accessed 4 August 2012.

- Willson, E.I., West London Nursery Gardens, 1982, pp. 109–10. ISBN 978-0-901643-03-2.

|