John (Jean) Pierre Burr

| John Pierre Burr | |

|---|---|

John Pierre Burr, Year unknown | |

| Born |

circa 1792 New Jersey or Pennsylvania, USA |

| Died |

April 4, 1864 (aged 72) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Nationality | American |

| Movement | African-American Civil Rights Movement |

| Spouse(s) | Hester Elizabeth Emory |

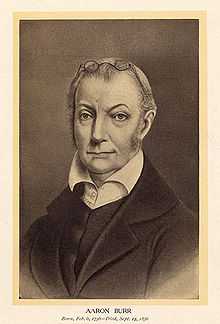

John Pierre Burr (abt 1792 – 4 April 1864) was an American abolitionist and community leader in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, active in education and civil rights for African Americans. He was the natural child of Mary Emmons, an East Indian servant born in Calcutta, and the third U.S. Vice President, Aaron Burr Jr. He is buried at olive cemetery, which is now part of Eden cemetery in Philadelphia.

Early life and education

John (Jean) Pierre Burr was born in 1792 in either New Jersey or Philadelphia to Mary Emmons, aka Eugénie Bearhani (phonetic spelling), an East Indian woman said to be from Calcutta.[1] She worked as a servant in the household of politician Aaron Burr and his second wife Theodosia Bartow Prevost. Mary/Eugénie was said to have lived and worked in Saint-Domingue before being brought to Philadelphia;[1] an early source said that she was born there.[2] She may have been brought to Philadelphia by Theodosia's first husband, Jacques Marcus Prevost, a British military officers who was stationed in the West Indies in the early 1770s.

Burr had an older sister, Louisa Charlotte Burr, born 1788, also the daughter of Aaron Burr and Mary Emmons.[1] Louisa Burr worked most of her life as a valued servant in the household of Philadelphia society matron, Elizabeth Powel Francis Fisher, and after her death, in the home of Mrs. Fisher's only child, Joshua Francis Fisher.[3] Louisa Burr married Francis Webb (1788-1829), a founding member of the Pennsylvania Augustine Education Society, secretary of the Haytien Emigration Society formed in 1824, and distributor of Freedom’s Journal from 1827-1829.[3] Her son (and John Pierre Burr's nephew), Frank J. Webb, wrote the second African American novel, The Garies and Their Friends, published in 1857. [3]

Marriage and family

Burr married Hester Elizabeth Emory at African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia in 1817. They had at least nine children, including John Emory Burr, who became a barber like his father and a Grand Master of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows in America, a fraternal organization. The family shared a commitment to the antislavery struggle, particularly his wife Hetty, their daughter J. Matilda, and their sons, John Emory and David. Other siblings were Edward and Martin, who became carpenters. The Philadelphia Preservation Alliance said the Burr house was at 5th and Spruce streets, in the Society Hill area of the city. Hetty also worked in business, having an employment office, and by 1860 was a dressmaker together with her unmarried daughters Elizabeth and Louisa.[2]

Career

John P. Burr worked as a barber in the city and by 1818 had his own business, when this was a service used by many middle-class men.

He also became an abolitionist and an active member of the Underground Railroad.[2] He was active on issues of civil rights and helped organize the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society,[2] serving on its Vigilance Committee to directly aid fugitive slaves. This was one of a number of reform efforts for which he was active. As a free state, Pennsylvania had abolished slavery after the Revolution; it offered freedom to those slaves brought to the state voluntarily by their masters. In addition, as it bordered states of the Upper South, the state and its waterways became destinations for fugitive slaves. Burr would hide runaways in his house. Because Burr was of mixed race and light-skinned, he often accompanied refugees to their next stop in the city or environs. If they were questioned by police, he would simply say he was taking “his man” (personal servant) out for a walk.

Absalom Jones had founded the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia in 1782 as the first black Episcopal congregation, and in 1804 was ordained as the first black Episcopal priest. As an adult, Burr was a member and worked with Jones to build the congregation's second church; he also helped develop the membership, among whom were many leaders in the black community.

J.P. Burr’s activities ranged from promoting emigration by American blacks to Haiti after it founded its republic, to serving as an agent for the abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, published by William Lloyd Garrison in Boston and distributed nationally. He worked on civil rights, protesting disfranchisement of free blacks by the state legislature in 1838, and sheltering fugitive slaves. Together with other members of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, Burr helped raise money for the defense of men indicted for treason for what was then called the Christiana Riot of 1851 and is now known as the Christiana Resistance in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.[2][4] The mixed group of blacks and whites had resisted US Marshals and slaveholders trying to capture fugitive slaves who had been living in southern Pennsylvania; this incident was part of popular resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. After the first suspect was rapidly acquitted, the federal prosecutor dropped charges against the other defendants.[5]

Chairman of the board of the American Moral Reform Society, Burr helped publish its journal, the National Reformer.[2] He was involved in the National Black Convention movement of the early 1830s. Burr served as an officer for the Mechanics’ Enterprise Hall, the Moral Reform Retreat (a refuge for black alcoholics), and the Colored Citizens of Philadelphia.[2] He worked with other leaders such as Robert Purvis and Rev. William Catto, father of Octavius Catto.

With associates, he founded the Demosthenian Institute at his home on January 10, 1837.[6] First known as a literary society, its members trained young black men in their early 20s to prepare for public speaking,[7] like a Toastmasters of its time. They took turns preparing and giving speeches, discussed current political topics, and answered questions posed by fellow members. They intended the Institute to be a kind of preparatory school until members gained experience and skills in public speaking. By 1841 the Institute had forty-two members, and their library had collected more than 100 scientific and historical works. The Demosthenian Shield, their weekly paper, was first published on June 29, 1841, as the organ of the Institute.[7] It had some guidance from staff of the Colored American, an established black newspaper of the time.[7] Organizers collected a subscription list of more than 1,000 persons to support the paper before its first issue was published.[7][8]

With his activities and leadership skills, Burr was a member of the elite class of free blacks in Philadelphia. He was among those who signed Frederick Douglass’ “Men of Color to Arms” poster for recruiting during the Civil War. He also met with members of the Quakers, many of whom supported abolition, such as John Greenleaf Whitter. The poet later wrote about Burr in his letters. [9]

Legacy and honors

- Burr aided many refugees from slavery on the Underground Railroad.

- Together with his wife and some of their children, he was active in fraternal organizations that worked for education, charity and civil rights for the African-American community.

- His descendants Mable Burr Cornish and Louella Burr Mitchell Allen saved and collected documentation, photos and oral histories that recount his period, the First African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, and the achievements of him and his family. These have been shared with the Aaron Burr Association and historical societies, to ensure their preservation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ip, Greg. "Aaron Burr fans find unlikely ally in black descendant". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. October 5, 2005.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Winch, Julie, ed., Willson, Joseph. The Elite of Our People: Joseph Willson's Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Maillard, Mary. "“Faithfully Drawn from Real Life” Autobiographical Elements in Frank J. Webb's The Garies and Their Friends", Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 137.3 (2013): 261-300.

- ↑ Ballard, Allen. One More Day's Journey, iUniverse, 27 April 2004. Retrieved on 14 March 2014.

- ↑ The Christiana Riot 1851 John Anderson, BlackPast.org.

- ↑ Demosthenian Institute, Special Collections, University of Detroit Mercy.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Logan, Shirley Wilson. Liberating Language: Sites of Rhetorical Education in Nineteenth-century Black America, SIU Press, 2008, p.62.

- ↑ Porter, Dorothy. “The Organized Educational Activities of Negro Literary Societies", 1936, at Autodidact.

- ↑ Pickard, Samuel.Life and Letters of John Greenleaf Whittier, Volume 1, 1894.