Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach[1] (31 March [O.S. 21 March] 1685 – 28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the Baroque period. He enriched established German styles through his skill in counterpoint, harmonic and motivic organisation, and the adaptation of rhythms, forms, and textures from abroad, particularly from Italy and France. Bach's compositions include the Brandenburg Concertos, the Goldberg Variations, the Mass in B minor, two Passions, and over three hundred sacred cantatas of which nearly two hundred survive.[2] His music is revered for its technical command, artistic beauty, and intellectual depth.

Bach was born in Eisenach, Saxe-Eisenach, into a great musical family. His father, Johann Ambrosius Bach, was the director of the town musicians, and all of his uncles were professional musicians. His father probably taught him to play the violin and harpsichord, and his brother, Johann Christoph Bach, taught him the clavichord and exposed him to much contemporary music.[3] Apparently at his own initiative, Bach attended St. Michael's School in Lüneburg for two years. After graduating he held several musical posts across Germany: he served as Kapellmeister (director of music) to Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen, Cantor of the Thomasschule in Leipzig, and Royal Court Composer to Augustus III.[4][5] Bach's health and vision declined in 1749, and he died on 28 July 1750. Modern historians believe that his death was caused by a combination of stroke and pneumonia.[6][7][8]

Bach's abilities as an organist were respected throughout Europe during his lifetime, although he was not widely recognised as a great composer until a revival of interest and performances of his music in the first half of the 19th century. He is now generally regarded as one of the greatest composers of all time.[9]

Life

Childhood (1685–1703)

Johann Sebastian Bach was born in Eisenach, Saxe-Eisenach, on 21 March 1685 O.S. (31 March 1685 N.S.). He was the son of Johann Ambrosius Bach, the director of the town musicians, and Maria Elisabeth Lämmerhirt.[10] He was the eighth child of Johann Ambrosius, (the eldest son in the family was 14 at the time of Bach's birth)[11] who probably taught him violin and the basics of music theory.[12] His uncles were all professional musicians, whose posts included church organists, court chamber musicians, and composers. One uncle, Johann Christoph Bach (1645–93), introduced him to the organ, and an older second cousin, Johann Ludwig Bach (1677–1731), was a well-known composer and violinist. Bach drafted a genealogy around 1735, titled "Origin of the musical Bach family".[13]

Bach's mother died in 1694, and his father died eight months later.[5] Bach, aged 10, moved in with his oldest brother, Johann Christoph Bach (1671–1721), the organist at St. Michael's Church in Ohrdruf, Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg.[14] There he studied, performed, and copied music, including his own brother's, despite being forbidden to do so because scores were so valuable and private and blank ledger paper of that type was costly.[15][16] He received valuable teaching from his brother, who instructed him on the clavichord. J.C. Bach exposed him to the works of great composers of the day, including South German composers such as Johann Pachelbel (under whom Johann Christoph had studied) and Johann Jakob Froberger; North German composers;[3] Frenchmen, such as Jean-Baptiste Lully, Louis Marchand, Marin Marais; and the Italian clavierist Girolamo Frescobaldi. Also during this time, he was taught theology, Latin, Greek, French, and Italian at the local gymnasium.[17]

At the age of 14, Bach, along with his older school friend Georg Erdmann, was awarded a choral scholarship to study at the prestigious St. Michael's School in Lüneburg in the Principality of Lüneburg.[18] Although it is not known for certain, the trip was likely taken mostly on foot.[17] His two years there were critical in exposing him to a wider facet of European culture. In addition to singing in the choir he played the School's three-manual organ and harpsichords.[17] He came into contact with sons of noblemen from northern Germany sent to the highly selective school to prepare for careers in other disciplines.

While in Lüneburg, Bach had access to St. John's Church and possibly used the church's famous organ, built in 1549 by Jasper Johannsen, since it was played by his organ teacher Georg Böhm.[19] Given his musical talent, Bach had significant contact with Böhm while a student in Lüneburg, and also took trips to nearby Hamburg where he observed "the great North German organist Johann Adam Reincken".[19][20] Stauffer reports the discovery in 2005 of the organ tablatures that Bach wrote out when still in his teens of works by Reincken and Dieterich Buxtehude, showing "a disciplined, methodical, well-trained teenager deeply committed to learning his craft".[19]

Weimar, Arnstadt, and Mühlhausen (1703–08)

In January 1703, shortly after graduating from St. Michael's and being turned down for the post of organist at Sangerhausen,[21] Bach was appointed court musician in the chapel of Duke Johann Ernst III in Weimar.[22] His role there is unclear, but likely included menial, non-musical duties. During his seven-month tenure at Weimar, his reputation as a keyboardist spread so much that he was invited to inspect the new organ, and give the inaugural recital, at St. Boniface's Church in Arnstadt, located about 30 kilometres (19 mi) southwest of Weimar.[23] In August 1703, he became the organist at St. Boniface's, with light duties, a relatively generous salary, and a fine new organ tuned in the modern tempered system that allowed a wide range of keys to be used.

Despite strong family connections and a musically enthusiastic employer, tension built up between Bach and the authorities after several years in the post. Bach was dissatisfied with the standard of singers in the choir, while his employer was upset by his unauthorised absence from Arnstadt; Bach was gone for several months in 1705–06, to visit the great organist and composer Dieterich Buxtehude and his Abendmusiken at St. Mary's Church in the northern city of Lübeck. The visit to Buxtehude involved a 450-kilometre (280 mi) journey each way, reportedly on foot.[24]

In 1706, Bach was offered a post as organist at St. Blasius's Church in Mühlhausen, which he took up the following year. It included significantly higher remuneration, improved conditions, and a better choir. Four months after arriving at Mühlhausen, Bach married Maria Barbara Bach, his second cousin. They had seven children, four of whom survived to adulthood, including Wilhelm Friedemann Bach and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach who both became important composers as well. Bach was able to convince the church and town government at Mühlhausen to fund an expensive renovation of the organ at St. Blasius's Church. Bach, in turn, wrote an elaborate, festive cantata—Gott ist mein König (BWV 71)—for the inauguration of the new council in 1708. The council paid handsomely for its publication, and it was a major success.[17]

Return to Weimar (1708–17)

In 1708, Bach left Mühlhausen, returning to Weimar this time as organist and from 1714 Konzertmeister (director of music) at the ducal court, where he had an opportunity to work with a large, well-funded contingent of professional musicians.[17] Bach moved with his family into an apartment very close to the ducal palace. In the following year, their first child was born and Maria Barbara's elder, unmarried sister joined them. She remained to help run the household until her death in 1729.

Bach's time in Weimar was the start of a sustained period of composing keyboard and orchestral works. He attained the proficiency and confidence to extend the prevailing structures and to include influences from abroad. He learned to write dramatic openings and employ the dynamic motor rhythms and harmonic schemes found in the music of Italians such as Vivaldi, Corelli, and Torelli. Bach absorbed these stylistic aspects in part by transcribing Vivaldi's string and wind concertos for harpsichord and organ; many of these transcribed works are still regularly performed. Bach was particularly attracted to the Italian style in which one or more solo instruments alternate section-by-section with the full orchestra throughout a movement.[26]

In Weimar, Bach continued to play and compose for the organ, and to perform concert music with the duke's ensemble.[17] He also began to write the preludes and fugues which were later assembled into his monumental work The Well-Tempered Clavier (Das Wohltemperierte Clavier—"Clavier" meaning clavichord or harpsichord),[27] consisting of two books, compiled in 1722 and 1744,[28] each containing a prelude and fugue in every major and minor key.

Also in Weimar Bach started work on the Little Organ Book, containing traditional Lutheran chorales (hymn tunes) set in complex textures. In 1713, Bach was offered a post in Halle when he advised the authorities during a renovation by Christoph Cuntzius of the main organ in the west gallery of the Market Church of Our Dear Lady. Johann Kuhnau and Bach played again when it was inaugurated in 1716.[29][30]

In the spring of 1714, Bach was promoted to Konzertmeister, an honour that entailed performing a church cantata monthly in the castle church.[31] The first three cantatas Bach composed in Weimar were Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 182, for Palm Sunday, which coincided with the Annunciation that year, Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12, for Jubilate Sunday, and Erschallet, ihr Lieder, erklinget, ihr Saiten! BWV 172 for Pentecost.[32] Bach's first Christmas cantata Christen, ätzet diesen Tag, BWV 63 was premiered in 1714 or 1715.[33][34]

In 1717, Bach eventually fell out of favour in Weimar and was, according to a translation of the court secretary's report, jailed for almost a month before being unfavourably dismissed: "On November 6, [1717], the quondam concertmaster and organist Bach was confined to the County Judge's place of detention for too stubbornly forcing the issue of his dismissal and finally on December 2 was freed from arrest with notice of his unfavourable discharge."[35]

Köthen (1717–23)

Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen hired Bach to serve as his Kapellmeister (director of music) in 1717. Prince Leopold, himself a musician, appreciated Bach's talents, paid him well, and gave him considerable latitude in composing and performing. The prince was Calvinist and did not use elaborate music in his worship; accordingly, most of Bach's work from this period was secular,[36] including the orchestral suites, the cello suites, the sonatas and partitas for solo violin, and the Brandenburg Concertos.[37] Bach also composed secular cantatas for the court such as Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a. A significant influence upon Bach's musical development during his years with the Prince is recorded by Stauffer as Bach's "complete embrace of dance music, perhaps the most important influence on his mature style other than his adoption of Vivaldi's music in Weimar".[19]

Despite being born in the same year and only about 130 kilometres (81 mi) apart, Bach and Handel never met. In 1719, Bach made the 35-kilometre (22 mi) journey from Köthen to Halle with the intention of meeting Handel, however Handel had left the town.[38] In 1730, Bach's son Wilhelm Friedemann travelled to Halle to invite Handel to visit the Bach family in Leipzig, but the visit did not come to pass.[39]

On 7 July 1720, while Bach was on travel to Carlsbad with Prince Leopold, Bach's first wife suddenly died.[40] The following year, he met Anna Magdalena Wilcke, a young, highly gifted soprano seventeen years his junior, who performed at the court in Köthen; they married on 3 December 1721.[41] Together they had thirteen more children, six of whom survived into adulthood: Gottfried Heinrich; Elisabeth Juliane Friederica (1726–81), who married Bach's pupil Johann Christoph Altnickol; Johann Christoph Friedrich and Johann Christian, who both became significant musicians; Johanna Carolina (1737–81); and Regina Susanna (1742–1809).[42]

Leipzig (1723–50)

In 1723, Bach was appointed Thomaskantor, Cantor of the Thomasschule at the Thomaskirche (St. Thomas Church) in Leipzig which served four churches in the city, the Thomaskirche, the Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas Church), the Neue Kirche and the Peterskirche,[43] and musical director of public functions such as city council elections and homages. This was a prestigious post in the mercantile city in the Electorate of Saxony, which he held for twenty-seven years until his death. It brought him into contact with the political machinations of his employer, Leipzig's city council.

Bach was required to instruct the students of the Thomasschule in singing and to provide church music for the main churches in Leipzig. Bach was required to teach Latin, but he was allowed to employ a deputy to do this instead. A cantata was required for the church services on Sundays and additional church holidays during the liturgical year. He usually performed his own cantatas, most of which were composed during his first three years in Leipzig. The first of these was Die Elenden sollen essen, BWV 75, first performed in the Nikolaikirche on 30 May 1723, the first Sunday after Trinity. Bach collected his cantatas in annual cycles. Five are mentioned in obituaries, three are extant.[32] Of the more than three hundred cantatas which Bach composed in Leipzig, over one hundred have been lost to posterity.[2] Most of these concerted works expound on the Gospel readings prescribed for every Sunday and feast day in the Lutheran year. Bach started a second annual cycle the first Sunday after Trinity of 1724, and composed only chorale cantatas, each based on a single church hymn. These include O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort, BWV 20, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140, Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 62, and Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern, BWV 1.

Bach drew the soprano and alto choristers from the School, and the tenors and basses from the School and elsewhere in Leipzig. Performing at weddings and funerals provided extra income for these groups; it was probably for this purpose, and for in-school training, that he wrote at least six motets.[44] As part of his regular church work, he performed other composers' motets, which served as formal models for his own.[45]

Bach's predecessor as Cantor, Johann Kuhnau, had also been music director for the Paulinerkirche, the church of Leipzig University. But when Bach was installed as Cantor in 1723, he was put in charge only of music for "festal" (church holiday) services at the Paulinerkirche; his petition to provide music also for regular Sunday services there (for corresponding salary increase) went all the way up to King Augustus II but was denied. After this, in 1725, Bach "lost interest" in working even for festal services at the Paulinerkirche and appeared there only on "special occasions".[46] The Paulinerkirche had a much better and newer (1716) organ than did the Thomaskirche or the Nikolaikirche. Bach had been consulted officially about the 1716 organ after its completion, came from Köthen, and submitted a report.[47] Bach was not required to play any organ in his official duties, but it is believed he liked to play on the Paulinerkirche organ "for his own pleasure".[48]

Bach broadened his composing and performing beyond the liturgy by taking over, in March 1729, the directorship of the Collegium Musicum, a secular performance ensemble started by the composer Georg Philipp Telemann. This was one of the dozens of private societies in the major German-speaking cities that was established by musically active university students; these societies had become increasingly important in public musical life and were typically led by the most prominent professionals in a city. In the words of Christoph Wolff, assuming the directorship was a shrewd move that "consolidated Bach's firm grip on Leipzig's principal musical institutions".[49] Year round, the Leipzig's Collegium Musicum performed regularly in venues such as the Café Zimmermann, a coffeehouse on Catherine Street off the main market square. Many of Bach's works during the 1730s and 1740s were written for and performed by the Collegium Musicum; among these were parts of his Clavier-Übung (Keyboard Practice) and many of his violin and keyboard concertos.[17]

In 1733, Bach composed a mass for the Dresden court (Kyrie and Gloria) which he later incorporated in his Mass in B minor. He presented the manuscript to the King of Poland, Grand Duke of Lithuania and Elector of Saxony, Augustus III in an eventually successful bid to persuade the monarch to appoint him as Royal Court Composer.[4] He later extended this work into a full mass, by adding a Credo, Sanctus and Agnus Dei, the music for which was partly based on his own cantatas, partly new composed. Bach's appointment as court composer was part of his long-term struggle to achieve greater bargaining power with the Leipzig council. Between 1737 and 1739, Bach's former pupil Carl Gotthelf Gerlach took over the directorship of the Collegium Musicum.

In 1747, Bach visited the court of King Frederick II at Potsdam. The king played a theme for Bach and challenged him to improvise a fugue based on his theme. Bach improvised a three-part fugue on one of Frederick's fortepianos, then a novelty, and later presented the king with a Musical Offering which consists of fugues, canons and a trio based on this theme. Its six-part fugue includes a slightly altered subject more suitable for extensive elaboration.

In the same year Bach joined the Corresponding Society of the Musical Sciences (Correspondierende Societät der musicalischen Wissenschaften) of Lorenz Christoph Mizler. On the occasion of his entry into the Society Bach composed the Canonic Variations on "Vom Himmel hoch da komm' ich her" (BWV 769).[50] A portrait had to be submitted by each member of the Society, so in 1746, during the preparation of Bach's entry, the famous Bach-portrait was painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann.[51] The Canon triplex á 6 Voc. (BWV 1076) on this portrait was dedicated to the Society.[52] Other late works by Bach may also have a connection with the music theory based Society.[53] One of those works was The Art of Fugue, which consists of 18 complex fugues and canons based on a simple theme.[54] The Art of Fugue was only published posthumously in 1751.[55]

Bach's last large work was the Mass in B minor (1748–49) which Stauffer describes as "Bach's most universal church work. Consisting mainly of recycled movements from cantatas written over a thirty-five year period, it allowed Bach to survey his vocal pieces one last time and pick select movements for further revision and refinement."[19] Although the complete mass was never performed during the composer's lifetime, it is considered to be among the greatest choral works of all time.[56]

Death (1750)

Bach's health declined in 1749; on 2 June, Heinrich von Brühl wrote to one of the Leipzig burgomasters to request that his music director, Johann Gottlob Harrer, fill the Thomaskantor and Director musices posts "upon the eventual ... decease of Mr. Bach".[57] Bach became increasingly blind, so the British eye surgeon John Taylor operated on Bach while visiting Leipzig in March or April 1750.[58]

On 28 July 1750 Bach died at the age of 65. A contemporary newspaper reported "the unhappy consequences of the very unsuccessful eye operation" as the cause of death.[59] Modern historians speculate that the cause of death was a stroke complicated by pneumonia.[6][7][8] His son Carl Philipp Emanuel and his pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola wrote an obituary of Bach.[60] In 1754, it was published by Lorenz Christoph Mizler in the musical periodical Musikalische Bibliothek. This obituary arguably remains "the richest and most trustworthy"[61] early source document about Bach.

Bach's estate included five harpsichords, two lute-harpsichords, three violins, three violas, two cellos, a viola da gamba, a lute and a spinet, and fifty-two "sacred books", including books by Martin Luther and Josephus.[62] He was originally buried at Old St. John's Cemetery in Leipzig. His grave went unmarked for nearly 150 years. In 1894, his remains were located and moved to a vault in St. John's Church. This building was destroyed by Allied bombing during World War II, so in 1950 Bach's remains were taken to their present grave in St. Thomas Church.[17] Later research has called into question whether the remains in the grave are actually those of Bach.[63]

Legacy

After his death, Bach's reputation as a composer at first declined; his work was regarded as old-fashioned compared to the emerging galant style.[64] Initially he was remembered more as a virtuoso player of the organ and as a teacher.

Many of Bach's unpublished manuscripts were distributed among his wife and musician sons at the time of his death. Unfortunately, the poor financial condition of some of the family members led to the sale and subsequent loss of parts of Bach's compositions, including over one hundred cantatas and his St Mark Passion, of which no copies are known to survive.[65]

During the late 18th and early 19th century, Bach was recognised by several prominent composers for his keyboard work. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Ludwig van Beethoven, Frédéric Chopin, Robert Schumann, and Felix Mendelssohn were among his admirers; they began writing in a more contrapuntal style after being exposed to Bach's music.[66] Beethoven described him as "Urvater der Harmonie", the "original father of harmony".[67]

Bach's reputation among the wider public was enhanced in part by Johann Nikolaus Forkel's 1802 biography of the composer.[68] Felix Mendelssohn significantly contributed to the renewed interest in Bach's work with his 1829 Berlin performance of the St Matthew Passion.[69] In 1850, the Bach-Gesellschaft (Bach Society) was founded to promote the works; in 1899 the Society published a comprehensive edition of the composer's works with little editorial intervention.

During the 20th century, the process of recognising the musical as well as the pedagogic value of some of the works continued, perhaps most notably in the promotion of the cello suites by Pablo Casals, the first major performer to record these suites.[70] Another development has been the growth of the historically informed performance movement, which attempts to take into account the aesthetic criteria and performance practice of the period in which the music was conceived. Examples include the playing of keyboard works on harpsichord rather than modern grand piano and the use of small choirs or single voices instead of the larger forces favoured by 19th- and early 20th-century performers.[71]

The liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church remembers Bach annually with a feast day on 28 July, together with George Frideric Handel and Henry Purcell; the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church, on the same day remembers Bach and Handel with Heinrich Schütz. In other circles, Bach's music is bracketed with the literature of William Shakespeare and the science of Isaac Newton.[72]

During the 20th century, many streets in Germany were named and statues were erected in honour of Bach. A large crater in the Bach quadrangle on Mercury is named in Bach's honour[73] as are the main-belt asteroids 1814 Bach and 1482 Sebastiana.[74] Bach's music features three times—more than that of any other composer—on the Voyager Golden Record, a gramophone record containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space with the two Voyager probes.[75]

Works

|

Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme (BWV 140)

opening chorale from cantata BWV 140, performed by the MIT Concert Choir Prelude No. 1 in C major (BWV 846)

from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 1, performed on harpsichord by Robert Schröter Aria from the Goldberg Variations (BWV 988)

opening aria from the Goldberg Variations, performed on piano by Kimiko Ishizaka |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

In 1950, a thematic catalogue called Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis (Bach Works Catalogue) was compiled by Wolfgang Schmieder.[76] Schmieder largely followed the Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe, a comprehensive edition of the composer's works that was produced between 1850 and 1900: BWV 1–224 are cantatas; BWV 225–249, large-scale choral works including his Passions; BWV 250–524, chorales and sacred songs; BWV 525–748, organ works; BWV 772–994, other keyboard works; BWV 995–1000, lute music; BWV 1001–40, chamber music; BWV 1041–71, orchestral music; and BWV 1072–1126, canons and fugues.[77]

Organ works

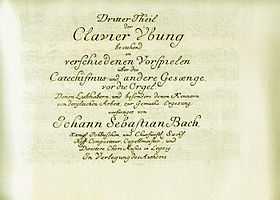

Bach was best known during his lifetime as an organist, organ consultant, and composer of organ works in both the traditional German free genres—such as preludes, fantasias, and toccatas—and stricter forms, such as chorale preludes and fugues.[17] At a young age, he established a reputation for his great creativity and ability to integrate foreign styles into his organ works. A decidedly North German influence was exerted by Georg Böhm, with whom Bach came into contact in Lüneburg, and Dieterich Buxtehude, whom the young organist visited in Lübeck in 1704 on an extended leave of absence from his job in Arnstadt. Around this time, Bach copied the works of numerous French and Italian composers to gain insights into their compositional languages, and later arranged violin concertos by Vivaldi and others for organ and harpsichord. During his most productive period (1708–14) he composed about a dozen pairs of preludes and fugues, five toccatas and fugues, and the Little Organ Book, an unfinished collection of forty-six short chorale preludes that demonstrates compositional techniques in the setting of chorale tunes. After leaving Weimar, Bach wrote less for organ, although some of his best-known works (the six trio sonatas, the German Organ Mass in Clavier-Übung III from 1739, and the Great Eighteen chorales, revised late in his life) were composed after his leaving Weimar. Bach was extensively engaged later in his life in consulting on organ projects, testing newly built organs, and dedicating organs in afternoon recitals.[78][79]

Other keyboard works

Bach wrote many works for harpsichord, some of which may have been played on the clavichord. Many of his keyboard works are anthologies that encompass whole theoretical systems in an encyclopaedic fashion.

- The Well-Tempered Clavier, Books 1 and 2 (BWV 846–893). Each book consists of a prelude and fugue in each of the 24 major and minor keys in chromatic order from C major to B minor (thus, the whole collection is often referred to as "the 48"). "Well-tempered" in the title refers to the temperament (system of tuning); many temperaments before Bach's time were not flexible enough to allow compositions to utilise more than just a few keys.[80][81]

- The Inventions and Sinfonias (BWV 772–801). These short two- and three-part contrapuntal works are arranged in the same chromatic order as The Well-Tempered Clavier, omitting some of the rarer keys. These pieces were intended by Bach for instructional purposes.[82]

- Three collections of dance suites: the English Suites (BWV 806–811), the French Suites (BWV 812–817), and the Partitas for keyboard (Clavier-Übung I, BWV 825–830). Each collection contains six suites built on the standard model (Allemande–Courante–Sarabande–(optional movement)–Gigue). The English Suites closely follow the traditional model, adding a prelude before the allemande and including a single movement between the sarabande and the gigue.[83] The French Suites omit preludes, but have multiple movements between the sarabande and the gigue.[84] The partitas expand the model further with elaborate introductory movements and miscellaneous movements between the basic elements of the model.[85]

- The Goldberg Variations (BWV 988), an aria with thirty variations. The collection has a complex and unconventional structure: the variations build on the bass line of the aria, rather than its melody, and musical canons are interpolated according to a grand plan. There are nine canons within the thirty variations, every third variation is a canon.[86] These variations move in order from canon at the unison to canon at the ninth. The first eight are in pairs (unison and octave, second and seventh, third and sixth, fourth and fifth). The ninth canon stands on its own due to compositional dissimilarities. The final variation, instead of being the expected canon at the tenth, is a quodlibet.

- Miscellaneous pieces such as the Overture in the French Style (French Overture, BWV 831) and the Italian Concerto (BWV 971) (published together as Clavier-Übung II), and the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue (BWV 903).

Among Bach's lesser known keyboard works are seven toccatas (BWV 910–916), four duets (BWV 802–805), sonatas for keyboard (BWV 963–967), the Six Little Preludes (BWV 933–938), and the Aria variata alla maniera italiana (BWV 989).

Orchestral and chamber music

Bach wrote for single instruments, duets, and small ensembles. Many of his solo works, such as his six sonatas and partitas for violin (BWV 1001–1006), six cello suites (BWV 1007–1012), and partita for solo flute (BWV 1013), are widely considered among the most profound works in the repertoire.[87] Bach composed a suite and several other works which have been claimed (since 1900) for the solo lute, but there is no evidence that he wrote for this instrument.[88] He wrote trio sonatas; solo sonatas (accompanied by continuo) for the flute and for the viola da gamba; and a large number of canons and ricercars, mostly with unspecified instrumentation. The most significant examples of the latter are contained in The Art of Fugue and The Musical Offering.

Bach's best-known orchestral works are the Brandenburg Concertos, so named because he submitted them in the hope of gaining employment from Margrave Christian Ludwig of Brandenburg-Schwedt in 1721; his application was unsuccessful.[17] These works are examples of the concerto grosso genre. Other surviving works in the concerto form include two violin concertos (BWV 1041 and BWV 1042); a concerto for two violins in D minor (BWV 1043), often referred to as Bach's "double" concerto; and concertos for one to four harpsichords. It is widely accepted that many of the harpsichord concertos were not original works, but arrangements of his concertos for other instruments now lost.[89] A number of violin, oboe, and flute concertos have been reconstructed from these. In addition to concertos, Bach wrote four orchestral suites, and a series of stylised dances for orchestra, each preceded by a French overture.[90]

Vocal and choral works

Cantatas

As the Thomaskantor, beginning mid of 1723, Bach performed a cantata each Sunday and feast day that corresponded to the lectionary readings of the week.[17] Although Bach performed cantatas by other composers, he composed at least three entire annual cycles of cantatas at Leipzig, in addition to those composed at Mühlhausen and Weimar.[17] In total he wrote more than three hundred sacred cantatas, of which nearly two hundred survive.[2][91]

His cantatas vary greatly in form and instrumentation, including those for solo singers, single choruses, small instrumental groups, and grand orchestras. Many consist of a large opening chorus followed by one or more recitative-aria pairs for soloists (or duets) and a concluding chorale. The recitative is part of the corresponding Bible reading for the week and the aria is a contemporary reflection on it. The melody of the concluding chorale often appears as a cantus firmus in the opening movement. Among his best known cantatas are:

- Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4

- Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 21

- Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80

- Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit, BWV 106 (Actus Tragicus)

- Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme, BWV 140

- Herz und Mund und Tat und Leben, BWV 147

In addition, Bach wrote a number of secular cantatas, usually for civic events such as council inaugurations. These include wedding cantatas, the Wedding Quodlibet, the Peasant Cantata, and the Coffee Cantata.[92]

Motets

Bach's motets (BWV 225–231) are pieces on sacred themes for choir and basso continuo, with instruments playing colla parte. Several of them were composed for funerals.[93] The six motets certainly composed by Bach are Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, Der Geist hilft unser Schwachheit auf, Jesu, meine Freude, Fürchte dich nicht, Komm, Jesu, komm, and Lobet den Herrn, alle Heiden. The motet Sei Lob und Preis mit Ehren (BWV 231) is part of the composite motet Jauchzet dem Herrn, alle Welt (BWV Anh. 160), other parts of which may be based on work by Telemann.[94]

Passions, oratorios, Magnificat

Bach's large choral-orchestral works include the grand scale St Matthew Passion and St John Passion, both written for Good Friday vesper services at the Thomaskirche and the Nikolaikirche in alternate years, and the Christmas Oratorio (a set of six cantatas for use in the liturgical season of Christmas).[95][96][97] Shorter works are the Easter Oratorio, the Ascension Oratorio, and the Magnificat.

Mass in B minor

Bach assembled his last large work, the Mass in B minor, near the end of his life, between 1748 and 1749. The mass was never performed in full during Bach's lifetime.[98][99] He incorporated the Sanctus of 1724 and the Missa in B minor, composed in 1733. He derived many movements from his cantatas, such as Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12, written in 1714, and composed some new movements. All of these movements have substantial solo parts as well as choruses. It is not known what direction of development Bach had intended for his last Mass to take. As Stauffer states, "If Bach had lived longer, it is likely that he would have created a definitive fair copy of the Mass, similar to those of the St. John and St. Matthew Passions... As Otto Bettmann once remarked, Bach's 'music sets in order what life cannot.'"[19]

Musical style

Bach's musical style arose from his skill in contrapuntal invention and motivic control, his flair for improvisation, his exposure to North and South German, Italian and French music, and his devotion to the Lutheran liturgy. His access to musicians, scores and instruments as a child and a young man and his emerging talent for writing tightly woven music of powerful sonority, allowed him to develop an eclectic, energetic musical style in which foreign influences were combined with an intensified version of the pre-existing German musical language. From the period 1713–14 onward he learned much from the style of the Italians.[100]

During the Baroque period, many composers only wrote the framework, and performers embellished this framework with ornaments and other elaboration.[101] This practice varied considerably between the schools of European music; Bach notated most or all of the details of his melodic lines, leaving little for performers to interpolate. This accounted for his control over the dense contrapuntal textures that he favoured, and decreased leeway for spontaneous variation of musical lines. At the same time, Bach left the instrumentation of major works including The Art of Fugue open.[102]

Bach's devout relationship with the Christian God in the Lutheran tradition[103] and the high demand for religious music of his times placed sacred music at the centre of his repertory.[104] He taught Luther's Small Catechism as the Thomaskantor in Leipzig, and some of his pieces represent it;[105] the Lutheran chorale hymn tune was the basis of much of his work. He wrote more cogent, tightly integrated chorale preludes than most. The large-scale structure of some of Bach's sacred works is evidence of subtle, elaborate planning. For example, the St Matthew Passion illustrates the Passion with Bible text reflected in recitatives, arias, choruses, and chorales.[106]

Bach's drive to display musical achievements was evident in his composition. He wrote much for the keyboard and led its elevation from continuo to solo instrument with harpsichord concertos and keyboard obbligato.[107] Bach produced collections of movements that explored the range of artistic and technical possibilities inherent in various genres. The most famous example is The Well-Tempered Clavier, in which each book presents a prelude and fugue in every major and minor key. Each fugue displays a variety of contrapuntal and fugal techniques.[108]

Performances

Present-day Bach performers usually pursue one of two traditions: so-called "authentic performance practice", utilising historical techniques; or the use of modern instruments and playing techniques, often with larger ensembles. In Bach's time orchestras and choirs were usually smaller than those of later composers, and even Bach's most ambitious choral works, such as his Mass in B minor and Passions, were composed for relatively modest forces. Some of Bach's important chamber music does not indicate instrumentation, which allows for a greater variety of ensembles.

Modern adaptations of Bach's music contributed greatly to Bach's popularisation in the second half of the 20th century. Among these were the Swingle Singers' versions of Bach pieces (for instance, the "Air" from Orchestral Suite No. 3, or the Wachet Auf... chorale prelude) and Wendy Carlos' 1968 Switched-On Bach, which used the Moog electronic synthesiser. Jazz musicians have adopted Bach's music, with Jacques Loussier, Ian Anderson, Uri Caine, and the Modern Jazz Quartet among those creating jazz versions of Bach works.[109]

See also

- List of fugal works by Johann Sebastian Bach

- List of transcriptions of compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach

- List of students of Johann Sebastian Bach

References

- ↑ German pronunciation: [joˈhan] or [ˈjoːhan zeˈbastjan ˈbaχ]; English pronunciation: /ˈbɑːx/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wolff (1997), p. 5

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Wolff (2000), pp. 19, 46

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "BACH Mass in B Minor BWV 232". The Baroque Music Site. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Miles (1962), pp. 86–87

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Breitenfeld, Tomislav; Vargek-Solter, Vesna; Breitenfeld, Darko; Zavoreo, Iris & Demarin, Vida (2006). "Johann Sebastian Bach's Strokes" (PDF). Acta Clinica Croatica (Sisters of Charity Hospital) 45 (1): 41–44.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baer, Karl A. (1956). "Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) in medical history". Bulletin of the Medical Library Association (Medical Library Association) 39 (3): 206–211. PMC 195117. PMID 14848627.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Breitenfeld, D.; Thaller, V.; Breitenfeld, T.; Golik-Gruber, V.; Pogorevc, T.; Zoričić, Z. & Grubišić, F. (2000). "The pathography of Bach's family". Alcoholism 36: 161–164.

- ↑ Blanning, T. C. W. (2008). The Triumph of Music: The Rise of Composers, Musicians and Their Art. p. 272.

And of course the greatest master of harmony and counterpoint of all time was Johann Sebastian Bach, 'the Homer of music'.

- ↑ Jones (2007), p. 3

- ↑ "Lesson Plans". Bach to School. The Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Boyd (2000), p. 6

- ↑ Printed in translation in David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 283

- ↑ Boyd (2000), pp. 7–8

- ↑ David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 299

- ↑ Wolff (2000), p. 45

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 17.9 17.10 17.11 "Johann Sebastian Bach: a detailed informative biography". The Baroque Music Site. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Wolff (2000), pp. 41–43

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.5 Stauffer, George B. (20 February 2014). "Why Bach Moves Us". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ↑ Geiringer (1966), p. 13

- ↑ Rich (1995), p. 27

- ↑ Boyd (2000), pp. 15–16

- ↑ Chiapusso (1968), p. 62

- ↑ Snyder, Kerala J. (2007). Dieterich Buxtehude: Organist in Lübeck (2nd ed.). pp. 104–106.

- ↑ Towe, Teri Noel. "The Portrait in Erfurt Alleged to Depict Bach, the Weimar Concertmeister". The Face Of Bach. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Thornburgh, Elaine. "Baroque Music – Part One". Music in Our World. San Diego State University. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Chiapusso (1968), p. 168

- ↑ Schweitzer (1935), p. 331

- ↑ Koster, Jan. "Weimar (II) 1708–1717". J.S. Bach Archive and Bibliography. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Sadie, Julie Anne, ed. (1998). Companion to Baroque Music. p. 205.

- ↑ Wolff (2000), pp. 147, 156

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Wolff (1991), p. 30

- ↑ Gardiner, John Eliot (2010). "Cantatas for Christmas Day: Herderkirche, Weimar" (PDF). pp. 1–2. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Wolff, Christoph (1996). "From konzertmeister to thomaskantor: Bach's cantata production 1713–1723" (PDF). pp. 15–16. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 80

- ↑ Miles (1962), p. 57

- ↑ Boyd (2000), p. 74

- ↑ Van Til (2007), pp. 69, 372

- ↑ Spaeth (1937), p. 37

- ↑ Spitta (1899), p. 11

- ↑ Geiringer (1966), p. 50

- ↑ Wolff (1983), pp. 98, 111

- ↑ Spitta (1899), p. 193

- ↑ "Motets BWV 225–231". Bach Cantatas Website. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ "Works of Other Composers performed by J.S. Bach". Bach Cantatas Website. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ↑ Boyd (2000), pp. 112–113

- ↑ Spitta (1899), pp. 288–290

- ↑ Spitta (1899), pp. 281, 287

- ↑ Wolff (2000), p. 341

- ↑ Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel & Agricola, Johann Friedrich (1754). "Denkmal dreyer verstorbenen Mitglieder der Societät der musikalischen Wissenschafften, [Nekrolog auf Johann Sebastian Bach]". Musikalische Bibliothek (in German) (Leipzig: Mizlerischen Bücherverlag) IV.1: 173.

- ↑ Musikalische Bibliothek, III.2 [1746], 353 (Source online), Felbick 2012, 284. In 1746, Mizler announced the membership of three famous members, Musikalische Bibliothek, III.2 [1746], 357 (Source online).

- ↑ Musikalische Bibliothek, IV.1 [1754], 108 and Tab. IV, fig. 16 (Source online); letter of Mizler to Spieß, 29 June 1748, in: Hans Rudolf Jung und Hans-Eberhard Dentler: Briefe von Lorenz Mizler und Zeitgenossen an Meinrad Spieß, in: Studi musicali 2003, Nr. 32, 115.

- ↑ Hans Gunter Hoke: Neue Studien zur »Kunst der Fuge« BWV 1080, in: Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 17 (1975), 95–115; Hans-Eberhard Dentler: Johann Sebastian Bachs »Kunst der Fuge« – Ein pythagoreisches Werk und seine Verwirklichung, Mainz 2004; Hans-Eberhard Dentler: Johann Sebastian Bachs »Musicalisches Opfer« – Musik als Abbild der Sphärenharmonie, Mainz 2008.

- ↑ Chiapusso (1968), p. 277

- ↑ "Did Bach really leave Art of Fugue unfinished?". The Art of Fugue. American Public Media. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Rathey, Markus (18 April 2003). Johann Sebastian Bach's Mass in B Minor: The Greatest Artwork of All Times and All People (PDF). The Tangeman Lecture. New Haven.

- ↑ Wolff (2000), p. 442, from David, Mendel & Wolff (1998)

- ↑ Hanford, Jan. "J.S. Bach: Timeline of His Life". J.S. Bach Home Page. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 188

- ↑ Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel & Agricola, Johann Friedrich (1754). "Denkmal dreyer verstorbenen Mitglieder der Societät der musikalischen Wissenschafften, [Nekrolog auf Johann Sebastian Bach]". Musikalische Bibliothek (in German) (Leipzig: Mizlerischen Bücherverlag) IV.1: 158–173. Printed in translation in David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 299.

- ↑ David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), p. 297

- ↑ David, Mendel & Wolff (1998), pp. 191–197

- ↑ Zegers, Richard H.C.; Maas, Mario; Koopman, A.G. & Maat, George J.R. (2009). "Are the alleged remains of Johann Sebastian Bach authentic?" (PDF). The Medical Journal of Australia 190 (4): 213–216.

- ↑ Bach was regarded as "passé even in his own lifetime". (Morris 2005, p. 2)

- ↑ Wolff (2000), pp. 456–461

- ↑ Schenk, Winston & Winston (1959), p. 452

- ↑ Kerst (1904), p. 101

- ↑ Geck (2006), pp. 9–10 (excerpt)

- ↑ Kupferberg (1985), p. 126

- ↑ "Robert Johnson and Pablo Casals' Game Changers Turn 70". NPR Music. National Public Radio. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ McComb, Todd M. "What is Early Music?–Historically Informed Performance". Early Music FAQ. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ "Biography of Johann Sebastian Bach". Piano Paradise. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Bach, USGS Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature

- ↑ 1814 Bach, 1482 Sebastiana, JPL Small-Body Database

- ↑ "Golden Record: Music from Earth". NASA. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ "Bach Works Catalogue". Bach Digital. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ↑ "Complete Works\by BWV Number–All". J.S. Bach Home Page. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bach, Johann Sebastian". GMN ClassicalPlus. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ↑ Smith, Timothy A. "Arnstadt (1703–1707)". The Canons and Fugues of J. S. Bach. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ↑ Schweitzer (1935), p. 333

- ↑ Kroesbergen, Willem & Cruickshank, Andrew (November 2013). "18th Century Quotes on J.S. Bach's Temperament". Academia.edu.

- ↑ Tomita, Yo. "J. S. Bach: Inventions and Sinfonias". Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ McComb, Todd M. "Bach: English Suites". Early Music FAQ. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "French Suites 1–6". Bach 101. The Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ McComb, Todd M. "Bach: Partitas, BWV 825–30". Early Music FAQ. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Libbey, Ted. "Gold Standard for Bach's 'Goldberg Variations'". NPR Music. National Public Radio. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Bratman, David. "Shaham: Bold, Brilliant, All-Bach". San Francisco Classical Voice. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Titmuss, Clive. "The Myth of Bach’s Lute Suites". This is Classical Guitar. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ "Baroque Music". Music of the Baroque. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "A compendium of works performed by the Bach Choir". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "Bach, Master of the Cantata". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "Cantata BWV 211, Coffee Cantata". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "Choral Works". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ Melamed, Daniel R. (1995). J. S. Bach and the German Motet. pp. 90–94.

- ↑ Leaver (2007), p. 430

- ↑ Williams (2003), p. 114

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "The Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ "The Mass in B Minor, BWV 232". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ↑ Herz (1985), p. 187

- ↑ Wolff (2000), p. 166

- ↑ Donington (1982), p. 91

- ↑ "Did Bach intend Art of Fugue to be performed?". The Art of Fugue. American Public Media. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Herl (2004), p. 123

- ↑ Fuller Maitland, J.A., ed. (1911). "Johann Sebastian Bach". Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians 1. New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 154.

- ↑ Leaver (2007), pp. 280, 289–291

- ↑ Huizenga, Tom. "A Visitor's Guide to the St. Matthew Passion". NPR Music. National Public Radio. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ Schulenberg (2006), pp. 1–2

- ↑ Traupman-Carr, Carol. "The Well Tempered Clavier BWV 846–869". Bach 101. Bach Choir of Bethlehem. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Shipton, Alyn. "Bach and Jazz". A Bach Christmas. BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

Bibliography

- Boyd, Malcolm (2000). Bach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-514222-5.

- Chiapusso, Jan (1968). Bach's World. Scarborough, Ontario: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-10520-X.

- David, Hans T.; Mendel, Arthur & Wolff, Christoph (1998). The New Bach Reader: A Life of Johann Sebastian Bach in Letters and Documents. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31956-3.

- Donington, Robert (1982). Baroque Music: Style and Performance: A Handbook. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-30052-8.

- Geck, Martin (2006). Johann Sebastian Bach: Life and Work. Orlando: Harcourt. ISBN 0-15-100648-2.

- Geiringer, Karl (1966). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Culmination of an Era. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-500554-6.

- Herl, Joseph (2004). Worship Wars in Early Lutheranism: Choir, Congregation, and Three Centuries of Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515439-8.

- Herz, Gerhard (1985). Essays on J.S. Bach. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. ISBN 978-0835719896.

- Jones, Richard (2007). The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816440-8.

- Kerst, Friedrich (1904). Beethoven im eigenen Wort (in German). Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler.

- Kupferberg, Herbert (1985). Basically Bach: A 300th Birthday Celebration. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-035646-7.

- Leaver, Robin A. (2007). Luther's Liturgical Music. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-3221-0.

- Miles, Russell H. (1962). Johann Sebastian Bach: An Introduction to His Life and Works. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall. OCLC 600065.

- Morris, Edmund (2005). Beethoven: the Universal Composer. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-075974-7.

- Rich, Alan (1995). Johann Sebastian Bach: Play by Play. San Francisco: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-263547-6.

- Schenk, Erich; Winston, Richard & Winston, Clara (1959). Mozart and his times. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 602180.

- Schulenberg, David (2006). The Keyboard Music of J.S. Bach. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-97400-3.

- Schweitzer, Albert (1935). J. S. Bach. Volume 1. New York: Macmillan Publishers.

- Spaeth, Sigmund (1937). Stories Behind the World's Great Music. New York: Whittlesey House.

- Spitta, Philipp (1899). Johann Sebastian Bach: His Work and Influence on the Music of Germany, 1685–1750. Volume 2. London: Novello & Co.

- Van Til, Marian (2007). George Frideric Handel: A Music Lover's Guide to His Life, His Faith & the Development of Messiah and His Other Oratorios. Youngstown, NY: WordPower Publishing. ISBN 0-9794785-0-2.

- Williams, Peter (2003). The Life of Bach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-53374-0.

- Wolff, Christoph (1991). Bach: Essays on his Life and Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-05926-3.

- Wolff, Christoph (2000). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-816534-X.

- Wolff, Christoph, ed. (1983). The New Grove Bach Family. London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 0-333-34350-6.

- Wolff, Christoph, ed. (1997). The World of the Bach Cantatas: Johann Sebastian Bach's Early Sacred Cantatas. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33674-0.

Further reading

- Baron, Carol K. (2006). Bach's Changing World: Voices in the Community. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 1-58046-190-5.

- Dörffel, Alfred (1882). Thematisches Verzeichnis der Instrumentalwerke von Joh. Seb. Bach (in German). Leipzig: C.F. Peters. N.B.: First published in 1867; superseded, for scholarly purposes, by Wolfgang Schmieder's complete thematic catalog, but useful as a handy reference tool for only the instrumental works of Bach and as a partial alternative to Schmieder's work.

- Eidam, Klaus (2001). The True Life of Johann Sebastian Bach. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-01861-0.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2013). Music in the Castle of Heaven: A Portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9662-3.

- Hofstadter, Douglas (1999). Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02656-7.

- Pirro, André (2014) [1907]. The Aesthetic of Johann Sebastian Bach. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3290-7.

- Stauffer, George B. & May, Ernest (1986). J. S. Bach as Organist: His Instruments, Music, and Performance Practices. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33181-1.

- Williams, Peter (2007). J. S. Bach: A Life in Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-87074-7.

External links

| German Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- J.S. Bach Home Page, by Jan Hanford—extensive information on Bach and his works; database of recordings and user reviews

- Bach Bibliography, by Yo Tomita of Queen's University Belfast—especially useful to scholars

- Bach Cantatas Website, by Aryeh Oron—information on the cantatas as well as other works

- Johann Sebastian Bach at the Musopen project

- Works by or about Johann Sebastian Bach at Internet Archive

Scores

- Free sheet music of Johann Sebastian Bach from Cantorion.org

- Free scores by Johann Sebastian Bach in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Johann Sebastian Bach at the International Music Score Library Project—the Bach-Gesellschaft-Ausgabe volumes split up into individual works, plus other editions

Recordings

- All of Bach website with a growing number of freely accessible recordings including HD videos and interviews by the Netherlands Bach Society and guest musicians

- The complete organ works of Bach performed by James Kibbie on German Baroque organs

- "Discovering Bach" material in the BBC Radio 3 archives

- "Exploring Bach" series at the Oregon Bach Festival

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|