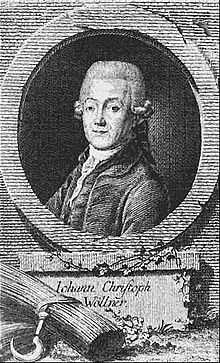

Johann Christoph von Wöllner

Johann Christoph von Wöllner (19 May 1732, Döberitz, Margraviate of Brandenburg - 10 September 1800, Grossriez near Beeskow) was a Prussian pastor and politician under King Frederick William II. He inclined to mysticism and joined the Freemasons and Rosicrucians.

Wöllner, whom Frederick the Great had described as a "treacherous and intriguing priest," had started life as a poor tutor in the family of General von Itzenplitz, a noble of the Margraviate of Brandenburg. After the general′s death and to the scandal of king and nobility, he married the general′s daughter, and with his mother-in-law′s assistance settled down on a small estate. By his practical experiments and by his writings he gained a considerable reputation as an economist; but his ambition was not content with this, and he sought to extend his influence by joining first the Freemasons and afterwards the Rosicrucians. Wöllner, with his impressive personality and easy if superficial eloquence, was just the man to lead a movement of this kind. Under his influence the order spread rapidly, and he soon found himself the supreme director (Oberhauptdirektor) of several circles, which included in their membership princes, officers and high officials. As a Rosicrucian Wöllner dabbled in alchemy and other mystic arts, but he was also zealous for Christian orthodoxy as well as the Enlightenment concept of religion as an important factor in maintaining public order.[1] A few months before Frederick II′s death, Wöllner wrote to his friend the Rosicrucian Johann Rudolph von Bischoffswerder (1741–1803) that his highest ambition was to be placed at the head of the religious department of the state as an unworthy instrument in the hand of Ormesus (the prince of Prussia's Rosicrucian name) "for the purpose of saving millions of souls from perdition and bringing back the whole country to the faith of Jesus Christ."

References

- ↑ Clark, Christopher (2006). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600 to 1947. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 270.