Jet (particle physics)

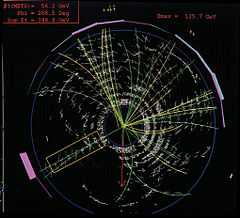

A jet is a narrow cone of hadrons and other particles produced by the hadronization of a quark or gluon in a particle physics or heavy ion experiment. Particles carrying a color charge, such as quarks, cannot exist in free form because of QCD confinement which only allows for colorless states. When an object containing color charge fragments, each fragment carries away some of the color charge. In order to obey confinement, these fragments create other colored objects around them to form colorless objects. The ensemble of these objects is called a jet. Jets are measured in particle detectors and studied in order to determine the properties of the original quarks.

In relativistic heavy ion physics, jets are important because the originating hard scattering is a natural probe for the QCD matter created in the collision, and indicate its phase. When the QCD matter undergoes a phase crossover into quark gluon plasma, the energy loss in the medium grows significantly, effectively quenching the outgoing jet.

Example of jet analysis techniques are:

- jet reconstruction (e.g., kT algorithm, cone algorithm)

- jet correlation

- flavor tagging (e.g., b-tagging).

The Lund string model is an example of a jet fragmentation model.

Jet production

Jets are produced in QCD hard scattering processes, creating high transverse momentum quarks or gluons, or collectively called partons in the partonic picture.

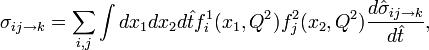

The probability of creating a certain set of jets is described by the jet production cross section, which is an average of elementary perturbative QCD quark, antiquark, and gluon processes, weighted by the parton distribution functions. For the most frequent jet pair production process, the two particle scattering, the jet production cross section in a hadronic collision is given by

with

- x, Q2: longitudinal momentum fraction and momentum transfer

-

: perturbative QCD cross section for the reaction ij → k

: perturbative QCD cross section for the reaction ij → k -

: parton distribution function for finding particle species i in beam a.

: parton distribution function for finding particle species i in beam a.

Elementary cross sections  are e.g. calculated to the leading order of perturbation theory in Peskin & Schroeder (1995), section 17.4. A review of various parameterizations of parton distribution functions and the calculation in the context of Monte Carlo event generators is discussed in T. Sjöstrand et al. (2003), section 7.4.1.

are e.g. calculated to the leading order of perturbation theory in Peskin & Schroeder (1995), section 17.4. A review of various parameterizations of parton distribution functions and the calculation in the context of Monte Carlo event generators is discussed in T. Sjöstrand et al. (2003), section 7.4.1.

Jet fragmentation

Perturbative QCD calculations may have colored partons in the final state, but only the colorless hadrons they ultimately produce are observed experimentally. Thus, to describe what is observed in a detector as a result of a given process, all outgoing colored partons must first undergo parton showering and then combination of the produced partons into hadrons. The terms fragmentation and hadronization are often used interchangeably in the literature to describe soft QCD radiation, formation of hadrons, or both processes together.

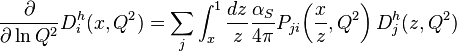

As the parton which was produced in a hard scatter exits the interaction, the strong coupling constant will increase with its separation. This increases the probability for QCD radiation, which is predominantly shallow-angled with respect to the originating parton. Thus, one parton will radiate gluons, which will in turn radiate qq pairs and so on, with each new parton nearly collinear with its parent. This can be described by convolving the spinors with fragmentation functions  , in a similar manner to the evolution of parton density functions. This is described by a Dokshitzer-Gribov-Lipatov-Altarelli-Parisi (DGLAP) type equation

, in a similar manner to the evolution of parton density functions. This is described by a Dokshitzer-Gribov-Lipatov-Altarelli-Parisi (DGLAP) type equation

Parton showering produces partons of successively lower energy, and must therefore exit the region of validity for perturbative QCD. Phenomenological models must then be applied to describe the length of time when showering occurs, and then the combination of colored partons into bound states of colorless hadrons, which is inherently not-perturbative. One example is the Lund String Model, which is implemented in many modern event generators.

References

- B. Andersson et al., "Parton Fragmentation and String Dynamics", Phys. Rep. 97(2–3), 31–145 (1983).

- S. D. Ellis, D. E. Soper, "Successive Combination Jet Algorithm For Hadron Collisions", Phys. Rev. D48, 3160–3166 (1993).

- M. Gyulassy et al., "Jet Quenching and Radiative Energy Loss in Dense Nuclear Matter", in R.C. Hwa & X.-N. Wang (eds.), Quark Gluon Plasma 3 (World Scientific, Singapore, 2003).

- J. E. Huth et al., in E. L. Berger (ed.), Proceedings of Research Directions For The Decade: Snowmass 1990, (World Scientific, Singapore, 1992), 134. (Preprint at Fermilab Library Server)

- M. E. Peskin, D. V. Schroeder, "An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory" (Westview, Boulder, CO, 1995).

- T. Sjöstrand et al., "Pythia 6.3 Physics and Manual", Report LU TP 03-38 (2003).

- G. Sterman, "QCD and Jets", Report YITP-SB-04-59 (2004).

See also

External links

- The Pythia/Jetset Monte Carlo event generator

- The FastJet jet clustering program