Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe, BWV 22

| Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe | |

|---|---|

| BWV 22 | |

| Church cantata by J. S. Bach | |

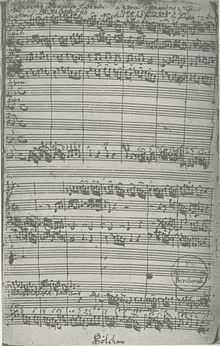

First page of the manuscript, bearing the title "Concerto Dominica Estomihi" (Concert for the Sunday before Lent), the scoring and the note "Das ist das Probe-Stück für Leipzig" (This is the test piece for Leipzig) | |

| Translation | Jesus gathered the twelve to Himself |

| Related | performed with BWV 23 |

| Occasion | Quinquagesima |

| Performed | 7 February 1723 – Leipzig |

| Movements | 5 |

| Cantata text | anonymous |

| Bible text | Luke 18:31,34 |

| Chorale | Herr Christ, der einig Gotts Sohn |

| Vocal |

|

| Instrumental |

|

Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe (Jesus gathered the twelve to Himself),[1] BWV 22[lower-alpha 1], is a church cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach composed for Quinquagesima, the last Sunday before Lent. Bach composed it as an audition piece for the position of Thomaskantor in Leipzig and first performed it there on 7 February 1723.

The work, which is in five movements, begins with a scene from the Gospel reading in which Jesus predicts his suffering in Jerusalem. The unknown poet of the cantata text took the scene as a starting point for a sequence of aria, recitative, and aria, in which the contemporary Christian takes the place of the disciples, who do not understand what Jesus is telling them about the events soon to unfold, but follow him nevertheless. The closing chorale is a stanza from Elisabeth Cruciger's hymn "Herr Christ, der einig Gotts Sohn". The music is scored for three vocal soloists, a four-part choir, oboe, strings and continuo. The work shows that Bach had mastered the composition of a dramatic scene, an expressive aria with obbligato oboe, a recitative with strings, an exuberant dance, and a chorale in the style of his predecessor in the position as Thomaskantor, Johann Kuhnau. Bach directed the first performance of the cantata during a church service, together with another audition piece, Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn, BWV 23. He performed the cantata again on the last Sunday before Lent a year later, after he had taken up office.

The cantata shows elements which became standards for Bach's Leipzig cantatas and even the Passions, including a "frame of biblical text and chorale around the operatic forms of aria and recitative", "the fugal setting of biblical words"[2] and "the biblical narrative ... as a dramatic scena".[3]

History

Background, Mühlhausen, Weimar and Köthen

Johann Sebastian Bach was an organist in Mühlhausen from 1706 to 1708. There he occasionally composed cantatas, mostly for special occasions. The cantatas were based mainly on biblical texts and hymns, such as Aus der Tiefen rufe ich, Herr, zu dir, BWV 131, and the early chorale cantata Christ lag in Todes Banden, BWV 4 for Easter.[4]

Bach was next appointed organist and chamber musician in Weimar on 25 June 1708 at the court of the co-reigning dukes in Saxe-Weimar, Wilhelm Ernst and his nephew Ernst August.[5] He initially concentrated on the organ, composing major works for the instrument,[5] including the Orgelbüchlein, the Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565, and the Prelude and Fugue in E major, BWV 566. He was promoted to Konzertmeister on 2 March 1714, an honour that entailed performing a church cantata monthly in the Schlosskirche:[6] The first cantatas he composed in the new position were Himmelskönig, sei willkommen, BWV 182, for Palm Sunday,[7] Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen, BWV 12 for Jubilate Sunday,[8] and Erschallet, ihr Lieder, BWV 172, for Pentecost. Mostly inspired by texts by the court poet, Salomo Franck, they contain recitatives and arias.[9] When Johann Samuel Drese, the Kapellmeister (director of music), died in 1716, Bach hoped in vain to become his successor. Bach looked for a better position and found it as Kapellmeister at the court of Leopold, Prince of Anhalt-Köthen. However, the duke in Weimar did not dismiss him and arrested him for disobedience. He was released on 2 December 1717.[10]

In Köthen, Bach found an employer who was an enthusiastic musician himself.[10] The court was Calvinist, therefore Bach's work from this period was mostly secular, including the orchestral suites, the cello suites, the sonatas and partitas for solo violin, and the Brandenburg Concertos.[10][11] He composed secular cantatas for the court for occasions such as New Year's Day and the prince's birthday, including Die Zeit, die Tag und Jahre macht, BWV 134a. He later parodied some of them as church cantatas without major changes, for example Ein Herz, das seinen Jesum lebend weiß, BWV 134.[12]

Audition in Leipzig

Bach composed his cantata as part of his application for the position of Thomaskantor in Leipzig,[13] the official title being Cantor et Director Musices[14] (Cantor and Director of Music). As cantor, he was responsible for the music at four Lutheran churches,[15] the main churches Thomaskirche (St. Thomas) and the Nikolaikirche (St. Nicholas),[16] but also the Neue Kirche (New Church) and the Peterskirche (St. Peter).[17][18] As director of music, the Thomaskantor was Leipzig's "senior musician", responsible for the music on official occasions such as town council elections and homages.[15] Functions related to the university took place at the Paulinerkirche..[16] The position became vacant when Johann Kuhnau died on 5 June 1722. Bach was interested, mentioning as one reason that he saw more possibilities for future academic studies of his sons in Leipzig: "... but this post was described to me in such favorable terms that finally (particularly since my sons seemed inclined to [university] studies) I cast my lot, in the name of the Lord, and made my journey to Leipzig, took my examination, and then made the change of position."[19]

-

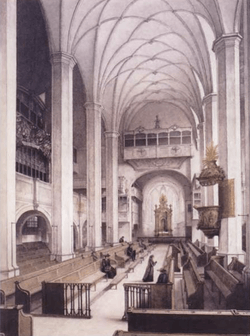

Thomaskirche,

1885 -

Nikolaikirche, ca. 1850 -

Neue Kirche,

1749 -

Peterskirche, before 1886 -

_Foto_H.-P._Haack_(berarb.).jpg)

Paulinerkirche,

1749

Audition in Leipzig

By August 1722, the town council had already chosen Georg Philipp Telemann as Kuhnau's successor, but he declined in November. In a council meeting on 23 November, seven candidates were evaluated, but no agreement was reached on whether to prefer a candidate for academic teaching abilities or musical performance. The first council document with Bach named as a candidate dates from 21 December, together with Christoph Graupner. Of all candidates, Bach was the only one without a university education.[20]

The decision to invite Bach was made by the council on 15 January 1723. The council seemed to have preferred Bach and Graupner because they were invited to show two cantatas each, while other candidates were requested to show only one. Two candidates even had to present their work in the same service. Graupner's performance took place on the last Sunday after Epiphany, 17 January 1723. Two days before the event, the town council already agreed to offer him the position.[21]

Christoph Wolff assumes that Bach received an invitation for the audition together with the texts, probably prescribed to the candidates and drawn from a printed collection, only weeks before the date.[22] Bach composed in Köthen two cantatas on two different themes from the prescribed Gospel for the Sunday, Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn, BWV 23, on the topic of healing the blind near Jericho,[16] Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe about Jesus announcing his suffering, which the disciples do not understand.[23]

Bach had to travel to Leipzig early because he was not familiar with the location and the performers. Wolff assumes that Bach was in Leipzig already on 2 February for the Marian feast of Purification when candidate Georg Balthasar Schott presented his audition piece at the Nikolaikirche.[22] Bach brought the scores and some parts, but additional parts had to be copied in Leipzig by students of the Thomasschule. Bach led the first performance of the two audition cantatas on 7 February 1723 as part of a church service at the Thomaskirche,[24] this cantata before the sermon, and Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn after the sermon.[13] The score of BWV 22 bears the note "This is the Leipzig audition piece" (Das ist das Probe-Stück für Leipzig).[25]

Wolff notes that Bach employed the three lower voices in BWV 22 and the upper three voices in BWV 23, and presents a list of the different composition techniques Bach employed in the two audition cantatas; they displayed "a broad and highly integrated spectrum of ... vocal art".[26]

| Cantata/Movement | Style |

|---|---|

| BWV 22/1B | Concerted choral fugue with solo exposition |

| BWV 23/3 | Concerted choral movement |

| BWV 22/5 | Hymn setting |

| BWV 22/3 | Secco recitative |

| BWV 23/2 | Recitative with instrumental cantus firmus |

| BWV 22/1A | Dialogue |

| BWV 22/2 | Aria in trio setting |

| BWV 23/1 | Duet in a five-part setting |

| BWV 22/4 | Aria with full string accompaniment |

| BWV 23/4 | Chorale fantasia |

A press review reads: "On Sunday last in the morning the Hon. Capellmeister of Cöthen, Mr. Bach, gave here his test at the church of St. Thomas's for the hitherto vacant cantorate, the music of the same having been amply praised on that occasion by all knowledgeable persons ...".[24]

Bach left Leipzig without hope for the position because it had been offered to Graupner, but he was not dismissed by his employer, Ernst-Ludwig of Hesse-Darmstadt.[24] After a meeting on 9 April 1723, with incomplete documentation containing "... since the best could not be obtained, a mediocre one would have to be accepted ...", Bach received an offer to sign a preliminary contract.[27]

Assuming the position

Bach assumed the position of Thomaskantor on 30 May 1723, the first Sunday after Trinity, performing two ambitious cantatas in 14 movements each: Die Elenden sollen essen, BWV 75, followed by Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes, BWV 76. They form the beginning of his attempt to create several annual cycles of cantatas for the occasions of the liturgical year.

He performed Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe again on 20 February 1724, as a printed libretto shows, and probably did so again in later years.[25]

Composition

Occasion and words

Bach composed his cantata in 1723 for the Sunday Quinquagesima which Bach knew as Estomihi, the last Sunday before Lent. In the city of Leipzig, tempus clausum was observed during Lent, therefore it was the last Sunday with a cantata performance before a celebration of the Annunciation, Palm Sunday and the vespers service on Good Friday and Easter.[28] The prescribed readings for the Sunday were taken from the First Epistle to the Corinthians, "praise of love" (1 Corinthians 13:1–13), and from the Gospel of Luke, healing the blind near Jericho (Luke 18:31–43). The Gospel also contains the announcement by Jesus of his future suffering in Jerusalem, and that the disciples do not understand what he is saying.

The cantata text is the usual combination of Bible quotation, free contemporary poetry and as closing chorale a stanza from a hymn as an affirmation. An unknown poet chose from the Gospel verses 31 and 34 as the text for movement 1, and wrote a sequence of aria, recitative and aria for the following movements. His poetic text places the Christian in general, including the listener at Bach's time or any time, in the situation of the disciples: he is pictured as wanting to follow Jesus even in suffering, although he does not comprehend.[16] The poetry ends on a prayer for "denial of the flesh". The closing chorale is stanza 5 of Elisabeth Cruciger's "Herr Christ, der einig Gotts Sohn",[29] intensifying the prayer,[30] on a melody from the Lochamer-Liederbuch.[31]

Stylistic comparisons with other works by Bach suggest that the same poet wrote the texts for both audition cantatas and also for the two first cantatas which Bach performed when taking up his office.[32] The poetry for the second aria has an unusually long first section, which Bach handled elegantly by repeating only part of it in the da capo.[33]

Scoring and structure

The cantata has five movements and is scored for three vocal soloists (an alto (A), tenor (T) and bass (B)), a four-part choir (SATB), and for a Baroque orchestra of an oboe (Ob), two violins (Vl), viola (Va) and basso continuo.[34] The duration is given as c. 20 minutes.[16]

In the following table of movements, the scoring, divided in voices, winds and strings, follows the Neue Bach-Ausgabe. The continuo group is not listed, because it plays throughout. The keys and time signatures are taken from Alfred Dürr. The symbol ![]() is used to denote common time (4/4).

is used to denote common time (4/4).

| No. | Type | Text (source) | Vocal | Winds | Strings | Key | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arioso | Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe (Bible) | T B SATB | Ob | 2Vl Va | G minor | |

| 2 | Aria | Mein Jesu, ziehe mich nach dir (anon.) | A | Ob | C minor | 9/8 | |

| 3 | Recitative | Mein Jesu, ziehe mich, so werd ich laufen (anon.) | B | E-flat major − B major | | ||

| 4 | Aria | Mein alles in allem, mein ewiges Gut (anon.) | T | 2Vl Va | B major | 3/8 | |

| 5 | Chorale | Ertöt uns durch dein Güte (Cruziger) | SATB | Ob | 2Vl Va | B major | |

Music

1

The text of the first movement, Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe (Jesus gathered the Twelve to Himself) is a quotation of two verses from the prescribed Gospel for the Sunday (Luke 18:31–43). The movement is a scene with different actors, narrated by the Evangelist (tenor), in which Jesus (bass, as the vox Christi or voice of Christ) and his disciples (the chorus) interact. An "ever-ascending" instrumental ritornello "evokes the image of the road of suffering embodied by going up to Jerusalem".[23] The Evangelist begins the narration (Luke 18:31). Jesus announces his future suffering in Jerusalem, Sehet, wir gehn hinauf gen Jerusalem ("Behold, we go up to Jerusalem").[1] He sings, while the ritornello is played several times.[16] After another repeat of the ritornello as an interlude, a choral fugue illustrates the reaction of the disciples, following verse 34 from the Gospel (Luke 18:34): Sie aber vernahmen der keines ("However they understood nothing").[1][16][25] The voices are first accompanied only by the continuo, then doubled by the other instruments. Bach marks the voices in the autograph score as "concertists" for the first section and "ripienists" when the instruments come in.[25]

The movement is concluded by an instrumental postlude.[30] The musicologist Julian Mincham notes that the fugue deviates from the "traditional alternating of tonic and dominant entries ... as a rather abstruse indication of the lack of clarity and expectation amongst the disciples, Bach is hinting at this in musical terms by having each voice enter on a different note, B-flat, F, C and G and briefly touching upon various related keys. The music is, as always, lucid and focussed but the departure from traditional fugal procedure sends a fleeting message to those who appreciate the subtleties of the musical processes".[35]

The musicologist Richard D. P. Jones points out that "the biblical narrative is set as a dramatic scena worthy of the Bach Passions" and that the "vivid drama of that movement has no real counterpart in Bach's Cycle I cantatas."[3]

2

In the first aria, Mein Jesu, ziehe mich nach dir ("My Jesus, draw me after You"),[1] the alto voice is accompanied by an obbligato oboe, which expressively intensifies the text.[30]

An aria is, according to Johann Mattheson in Der vollkommene Capellmeister (Part II, chapter 13, paragraph 10), "correctly described as a well-composed song, which has its own particular key and meter, is usually divided into two parts, and concisely expresses a great affection. Occasionally it closes with a repetition of the first part, occasionally without it."[36]

In this aria, an individual believer requests Jesus to make him follow, even without comprehending where and why. Mincham observes a mood or affekt of "deep involvement and pensive commitment", with the oboe creating "an aura of suffering and a sense of struggling and reaching upwards in search of something indefinable in a way that only music can suggest."[35]

3

The recitative Mein Jesu, ziehe mich, so werd ich laufen ("My Jesus, draw me, then I will run")[1] is not a simple secco recitative, but is accompanied by the strings and leans towards an arioso, especially near the end.[30] It is the first movement in a major mode, and illustrates in rapid runs the motion and the running mentioned..[35]

4

The second aria, Mein alles in allem, mein ewiges Gut ("My all in all, my eternal good"),[1] again with strings, is a dance-like movement in free da capo form, A B A'. The unusually long text, of four lines for the A section and two for the B section, results in Bach's solution to repeat the end of the first line (my eternal good) after all text of A, and then after the middle section B repeat only the first line as A', thus ending A and A' the same way.[33] In this modified repeat, the voice holds a long note on the word Friede ("peace"), after which the same theme appears in the orchestra and again in the continuo.[30] The musicologist Tadashi Isoyama notes the passepied character of the music, reminiscent of secular Köthen cantatas.[23] Mincham describes: "Bach's expression of the joy of union with Christ can often seem quite worldly and uninhibited", and summarises: "The 3/8 time signature, symmetrical phrasing and rapid string skirls combine to create a sense of a dance of abandonment."[35]

5

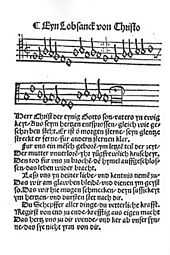

The closing chorale is Ertöt uns durch dein Güte ("Kill us through your goodness"[1] or "Us mortify through kindness"[37]), the fifth stanza of Elisabeth Cruciger's "Herr Christ, der einig Gotts Sohn".[29] Its melody is based on one from Wolflein Lochamer's Lochamer-Liederbuch, printed in Nürnberg around 1455. It first appears as a sacred tune in Johann Walter's Wittenberg hymnal Eyn geystlich Gesangk Buchleyn (1524).[31]

The usual four-part setting of the voices is brightened by continuous runs of the oboe and violin I.[35] Isoyama thinks that Bach may have intentionally imitated the style of his predecessor Johann Kuhnau in the "elegantly flowing obbligato for oboe and first violin".[38] John Eliot Gardiner describes the movement's bass line as a "walking bass as a symbol of the disciples' journey to fulfilment.[39] Mincham comments that Bach "chose to maintain the established mood of buoyancy and optimism with a chorale arrangement of almost unparalleled energy and gaiety" and concludes:

It would seem that Bach had not yet reached a conclusion, if indeed he ever did, as to the most appropriate way of utilising the chorales in his cantatas. Certainly the quiet, closing moments of reflection and introspection became the norm, particularly in the second cycle. But the chorale could, as here, act as a focus of bounding energy and positivity.[35]

Reception

Jones summarises: "The audition cantatas ... show Bach feeling his way towards a compromise between the progressive, opera-influenced and the conservative, ecclesiastical styles."[2] He acknowledges the standard BWV 22 sets for later church cantatas:

"... places an ecclesiastical frame of biblical text and chorale around the operatic forms of aria and recitative, a frame that would become a standard in the cantatas of cycle I. Moreover, the impressive opening movement incorporates two modes of treatment that would recur regularly during Cycle I and beyond: the fugal setting of biblical words and the use as the bass voice as vox Christi, as in traditional Passion settings."[2]

Isoyama points out: "BWV 22 incorporates dance rhythms, and is written with a modern elegance."[23] Mincham interprets Bach's approach in both audition works as "a fair example of the range of music which is suitable for worship and from which others might learn", explaining the "sheer range of forms and musical expression in these two cantatas".[35]

Gardiner, who conducted the Bach Cantata Pilgrimage with the Monteverdi Choir and wrote a diary on the project, comments on the disciples' reaction ("and they understood none of these things, neither knew they the things which were spoken"): "One could read into this an ironic prophecy of the way Bach's new Leipzig audience would react to his creative outpourings over the next twenty-six years – in the absence, that is, of any tangible or proven signs of appreciation: neither wild enthusiasm, deep understanding nor overt dissatisfaction".[39]

Recordings

The listing follows the selection on the Bach-Cantatas website.[40]

| Album | Conductor | Choir | Orchestra | Soloists | Label | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The RIAS Bach Cantatas Project (1949–1952) | Ristenpart, KarlKarl Ristenpart | RIAS-Kammerchor | RIAS-Kammerorchester | Lotte Wolf-Matthäus Helmut Krebs Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau |

Audite | 1950 |

| J.S. Bach: Das Kantatenwerk – Sacred Cantatas Vol. 2 | Leonhardt, GustavGustav Leonhardt | Tölzer Knabenchor, King's College Choir | Leonhardt Consort | Paul Esswood Kurt Equiluz Max van Egmond |

Teldec | 1973 |

| Die Bach Kantate Vol. 28 | Rilling, HelmuthHelmuth Rilling | Gächinger Kantorei | Bach-Collegium Stuttgart | Helen Watts Adalbert Kraus Wolfgang Schöne |

Hänssler | 1977 |

| J.S. Bach: Complete Cantatas Vol. 3 | Koopman, TonTon Koopman | Amsterdam Baroque Choir | Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra | Elisabeth von Magnus Paul Agnew Klaus Mertens |

Antoine Marchand | 1995 |

| J.S. Bach: Cantatas Vol. 8 – Leipzig Cantatas | Suzuki, MasaakiMasaaki Suzuki | Bach Collegium Japan | Bach Collegium Japan | Yoshikazu Mera Gerd Türk Peter Kooy |

BIS | 1998 |

| Bach Edition Vol. 5 – Cantatas Vol. 2 | Leusink, Pieter JanPieter Jan Leusink | Holland Boys Choir | Netherlands Bach Collegium | Sytse Buwalda Nico van der Meel Bas Ramselaar |

Brilliant Classics | 1999 |

| Bach Cantatas Vol. 21: Cambridge/Walpole St Peter | Gardiner, John EliotJohn Eliot Gardiner | Monteverdi Choir, the Choirs of Clare and Trinity Colleges | English Baroque Soloists | Claudia Schubert James Oxley Peter Harvey |

Soli Deo Gloria | 2000 |

| J.S. Bach: Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe, Kantate BWV 22 | Biller, Georg ChristophGeorg Christoph Biller | Thomanerchor | Gewandhausorchester | boy soloist of the Thomanerchor Martin Petzold Wolf Matthias Friedrich |

MDR Figaro | 2005 |

| J.S. Bach: Jesus, deine Passion | Herreweghe, PhilippePhilippe Herreweghe | Collegium Vocale Gent | Matthew White Jan Kobow Peter Kooy |

Harmonia Mundi France | 2007 | |

| Bach Cantatas From Mühlhausen, Weimar & Leipzig | Bates, JamesJames Bates | Carolina Baroque | Teresa Radomski Lee Morgan Richard Heard Doug Crawley |

Carolina Baroque | 2008 | |

| J.S. Bach: Kantate BWV 22 "Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe" | Lutz, RudolfRudolf Lutz | Chor der J. S. Bach-Stiftung | Orchester der J. S. Bach-Stiftung | Markus Forster Johannes Kaleschke Ekkehard Abele |

Gallus Media | 2010 |

Notes

- ↑ BWV is Bach-Werke-Verzeichnis, a thematical catalogue of Bach's works

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Dellal 2012.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jones 2013, p. 214.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jones 2013, p. 122.

- ↑ Arnold 2009, p. 37.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Koster 2011.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 147.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 156.

- ↑ Dürr 1971, p. 262.

- ↑ Dürr 1971, p. 29.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Randel 1996, p. 38.

- ↑ Loewe 2014, p. 54–55.

- ↑ Jones 2013, p. 213.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Wolff 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 237.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wolff 1991, p. 30.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Dürr 1971, p. 219.

- ↑ Peter 2015.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 251–252.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 221.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 218–221.

- ↑ Wolff 1991, p. 121.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Wolff 1991, p. 120.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Isoyama 1998, p. 4.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Wolff 1991, p. 128.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Wolff 1998, p. 20.

- ↑ Wolff 1991, p. 135.

- ↑ Wolff 2002, p. 223.

- ↑ Boulder 2014.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Browne & Oron 2009.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Dürr 1971, p. 220.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Browne & Oron 2008.

- ↑ Wolff 1991, p. 130.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Crist 1989, p. 44.

- ↑ Bischof 2012.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 Mincham 2010.

- ↑ Crist 1989, p. 36.

- ↑ Ambrose 2012.

- ↑ Isoyama 1998, p. 5.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Gardiner 2006, p. 2.

- ↑ Oron 2014.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to BWV 22. |

Scores

- Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe, BWV 22: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe BWV 22; BC A 48 / Sacred cantata (Estomihi)". Leipzig University. 1992. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

Books

- Arnold, Jochen (2009). Von Gott poetisch-musikalisch reden: Gottes verborgenes und offenbares Handeln in Bachs Kantaten (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-647-57124-5.

- Dürr, Alfred (1971). Die Kantaten von Johann Sebastian Bach (in German) 1. Bärenreiter-Verlag. OCLC 523584.

- Crist, Stephen A. (1989). Franklin, Don O., ed. Aria forms in the Cantatas from Bach' first Leipzig Jahrgang in Bach Studies 1. CUP Archive. ISBN 0-521-34105-1.

- Jones, Richard D. P. (2013). The Creative Development of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume II: 1717–1750: Music to Delight the Spirit. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-969628-4.

- Loewe, Arnold (2014). Johann Sebastian Bach’s St John Passion (BWV 245): A Theological Commentary. Brill. ISBN 9-00-427236-4.

- Randel, Don Michael (1996). The Harvard Biographical Dictionary of Music. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-37299-9.

- Wolff, Christoph (1991). Bach: Essays on His Life and Music. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05926-9.

- Wolff, Christoph (2002). Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32256-9.

Online sources

Several databases provide additional information on each cantata, such as history, scoring, sources for text and music, translations to various languages, discography, discussion and musical analysis.

The complete recordings of Bach's cantatas are accompanied by liner notes from musicians and musicologists: Gardiner commented on his Bach Cantata Pilgrimage, Klaus Hofmann and Tadashi Isoyama wrote for Masaaki Suzuki, and Wolff for Ton Koopman.

- Ambrose, Z. Philip (2012). "BWV 22 Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe". University of Vermont. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Bischof, Walter F. (2012). "BWV 22 Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe". University of Alberta. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Browne, Francis; Oron, Aryeh (2008). "Chorale Melodies used in Bach's Vocal Works / Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Browne, Francis; Oron, Aryeh (2009). "Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn / Text and Translation of Chorale". bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Dellal, Pamela (2012). "BWV 22 – "Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe"". Emmanuel Music. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Gardiner, John Eliot (2006). "Cantatas for Quinquagesima / King’s College Chapel, Cambridge" (PDF). bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Isoyama, Tadashi (1998). "BWV 22: Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe (Jesus called to Himself the Twelve)" (PDF). bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Koster, Jan (2011). "Weimar 1708–1717". let.rug.nl. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Mincham, Julian (2010). "Chapter 44 BWV 22 Jesu nahm zu sich die Zwölfe / Jesus took the twelve to Him.". jsbachcantatas.com. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Oron, Aryeh (2014). "Cantata BWV 22 Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe". bach-cantatas. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- Wolff, Christoph (1998). "From konzertmeister to thomaskantor: Bach's cantata production 1713–1723" (PDF). bach-cantatas.com. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- McCue, Edward (ed.). "The Liturgical Calendar at Leipzig". Boulder Bach Festival. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

| ||||||||||

|