Jesús Comín Sagüés

| Jesús Comín Sagüés | |

|---|---|

| Born |

Jesús Comín Sagüés 1889 Zaragoza, Spain |

| Died |

1939 Zaragoza, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | librarian, scholar |

| Known for | politician |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Jesús Comín Sagüés (Zaragoza, 1889 – Zaragoza, 1939) was a Spanish Carlist politician.

Family and Youth

The well established Aragonese Comín family for generations has been producing locally distinguished figures and also leaders of regional Traditionalism. Jesús's grand-grandfather sided with Carlos V during the First Carlist War and sought refuge in exile afterwards. His son, Bienvenido Comín Sarté, worked as a recognized lawyer and member of the Zaragoza ayuntamiento; he sided with Carlos VII during the Third Carlist War, having been member of the Royal Council and leader of the regional Junta Provincial Católico-Monárquica. He too had to flee abroad, though upon his return he grew to a distinguished scholar and writer; named marquess by Carlos VII (title recognized officially by Franco in 1959). His son and the uncle of Jesús, Pascual Comín Moya, was head of regional Carlism in the early 20th century and briefly served as the national Carlist leader in 1919. He resigned due to differences with the pretender Don Jaime over the international policy and conflict with other Carlist leaders, Francisco Martín de Melgar and Salvador Minguijón, though remained one of the national jaimistas leaders. Jesús' father, Francisco Comín Moya, has not occupied major posts in Carlism, though he became a recognized lawyer and scholar, assuming Cátedra de procedimientos judiciales y práctica forense of the University of Zaragoza in 1895 and becoming dean of the Facultad de derecho in 1921; married to Rosario Sagüés Mugiro.

In 1920 Jesús Comín Sagüés was married to a Catalan, María Pilar Ros Martínez (1896 – 1973); the couple had seven children. The only one which became a nationwide known figure was Alfonso Carlos Comín Ros (named after the then Carlist claimant, Don Alfonso Carlos), a politician, theorist and author. He gained recognition for theoretical attempt to merge militant Communism with Christianity, dubbed cristiano-marxismo; political prisoner in the Francoist Spain, he was one of the Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC) and Communist Party of Spain (PCE) leaders. María Pilar Comín Ros and Javier Comín Ros were locally known in Catalonia as contributors to the Barcelona daily La Vanguardia (María Pilar ran the section on women's fashion). Jesús' older brother, Francisco Javier, specialized in commercial law and served as catedratico in a number of Spanish universities.

Public servant

Jesús Comín Sagüés studied law in the Universidad de Zaragoza. Upon graduation he was employed by Biblioteca Universidaria de Zaragoza and in 1915 was admitted (as 3rd among 45 successful candidates) to Cuerpo facultativo de Archiveros, Bibliotecarios y Arqueólogos, the organization forming part of the state-run national heritage protection infrastructure, with the annual salary of 3,000 pesetas (in 1915 daily wage of a miner in Vizcay was 3,44 ptas). In 1919 Comín commenced work for Archivo de Hacienda de Zamora. Having obtained his PhD laurels in law, starting early 1920s he worked as one of the profesores auxiliares temporales at the Facultad de Filosofía y Letras in Zaragoza (his father was member of the Junta de Gobierno of the University at that time), continuing with his duties in national heritage institutions. He contributed to local and national cultural organizations, focusing on philosophy, literature and politics; active also in a number of Catholic associations, like Caballeros de Nuestra Señora del Pilar.

Restauración and dictatorship

Brought up in the tradition of his ancestors, Jesús Comín Sagüés from his early childhood was accustomed to Traditionalist realm and came to know personally many Carlist leaders, including the claimant Don Jaime himself. During his student years he became the youth activist and member of the then jaimist Carlist organization Comunión Católico-Monárquica (as opposed to the integrist Carlists, organized as Partido Católico Nacional). Thanks to his family links he gained prominence in the Aragon branch of the movement fairly early. When the secession of Juan Vázquez de Mella and his supporters seriously threatened the position of Don Jaime as the Carlist king in 1919, Comín entered Comité de Acción Jaimista, the loyalist body working to mobilize support for the pretender.

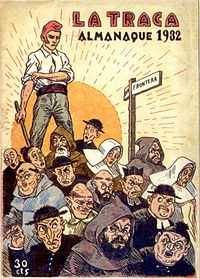

Comín's position as a prominent figure within the movement was demonstrated when he took part in works of the grand jaimista reunion named Junta Magna de Biarritz the same year, which pledged to defend the Catholic unity of Spain. This did not prevent gradual demise of all three branches of Carlism; in the early 1920s the jaimistas were reduced from 8 to 4 deputies to the Cortes and failed to elect a single MP from Aragon. Though initially they welcomed the Primo de Rivera dictatorship as means against the liberal democracy, later the followers of Don Jaime refrained from taking part in official politics, as in 1925 the pretender declared himself contrary to la dictadura.

Republic

Like most Traditionalists Comín welcomed the fall of the Alfonsine monarchy in 1931, though he was soon dismayed by the turn of events. The rising tide of republican, anarchist and socialist sympathies left the monarchists in disarray, failing to mount an immediate counter-action. The Carlists reacted in 1932 by merging three separate streams of the movement, the integristas, the mellistas and the jaimistas into the new joint structure, Comunión Tradicionalista; the unification was made easier by the death of Don Jaime and the Carlist claim to the throne passing to Don Alfonso Carlos. Within the new organization Comín became head of the Aragon branch, presiding over the rapid revitalization of Traditionalism in the region. In the 1933 general elections the Carlists won two parliamentary tickets (apart from Comín one seat went to Javier Ramirez Sinues), the largest ever electoral triumph of Carlism in Aragon, though the success was to a large extent the result of a broader Rightist alliance. Comín managed to retain his seat also in the 1936 elections.

Unlike other Carlists, rather vague as to the means expected to restore the traditionalist monarchy, Comín was fairly explicit about the necessity to introduce "national dictatorship", at least for some time. Following the 1934 revolution he was a member of the investigation committee sent to Catalonia afterwards. Within the group of Traditionalist deputies he joined the aristocratic faction led by Conde Rodezno which sought active alliance with the Alfonsinos monarchists in the National Bloc. Though such mixing with remnants of the usurpers' monarchy was much to the irritation of the new Carlist leader, Manuel Fal Conde, he acknowledged Comín's position of an erudite by appointing him to the Council of Culture, the body which exercised little real power but served (apart from diffusion of the ideology) the purpose in bringing together eminent Carlists of differing origins.

Comín remained a fairly active deputy; he worked in 3 parliamentary committees, namely these dedicated to public administration (also acting as its secretary), education and legal issues. He tended to focus on Aragon rather than on nationwide problems, rising questions of flood damages, regulation of the Ebro or underused railway hub in Canfranc (in this last case inducing the minister of economy to visiting the remote Aragon Pyrenees site). Some of his apparently local interventions had a wide impact; in case of the Ebro he protested against handing over some hydrographic competencies to the local Catalonian Generalitat government; in case of public unrest in Zaragoza he always favored firm measures against the workers. The nationwide issue which attracted his attention was an attempt to define anew the competencies of local self-governments; he clashed a number of times with the then CEDA deputy, Ramon Serrano Suñer. Comín gained many enemies when presenting a motion aiming at curtailing the liberties of Federación Universitaria Escolar, deemed responsible for unrest in the universities.

Civil War

The Carlists have never made a secret of their intention to do away with the godless Republic, but since the 1936 victory of Frente Popular they geared most of their efforts to violent overthrow of the democracy. The principal means envisaged was built-up of their paramilitary units; accordingly, Comín paid much attention to the Requeté organization. In mid-1935 Zaragoza was able to field only 2 piquetes (ca 70 men each); a year later the organization expanded by leaps and bounds; the city could have presented one tercio (ca 750 men) and emerged as one of the most mobilized centers, surpassed only by Pamplona, Bilbao, Barcelona, Valencia, Castellón and San Sebastián.

When the news of military rebellion in Morocco reached Zaragoza in the afternoon of July 18, 1936, the workers' militia took to the streets, while hundreds of Requetés headed for military barracks. The military commander of the district, general Miguel Cabanellas Ferrer admitted the Carlists and the Falangists to the garrison premises; at the same time he convinced the civil governor Ángel Vera Coronel of his loyalty. During the early morning hours of July 19 Cabanellas declared martial law, rounded up labor leaders and detained the governor. Comín travelled twice to Pamplona to secure reinforcements and during the next few days he came back with some 1,200 Navarrese Requetés. The Carlist militiamen helped to overwhelm pockets of workers' resistance in the city (engaging also in massive reprisal actions), overran the surrounding province and met the Barcelona Durruti anarchist column 22 km East of the Aragon capital, having established a frontline which lasted until late of the War. As a result Zaragoza, one of the national anarchist strongholds, remained firmly in Nationalists' hands.

Following the rebels' capture of Zaragoza Comín played a politically vital role. He strived to transform the Aragon rebellion from defense of the secular Republic against anarchy (as Cabanellas would have had it) into a monarchist, ultra-conservative and fanatically Catholic crusade, with Carlists tearing down the still flying republican flags, replacing them with the monarchist golden-red banners and staging religious feasts centered around Virgen del Pilar, the Catholics' patroness of the city. He threw himself into organizing the Requeté units, first forming the Tercio de Nuestra Seńora del Pilar and then other Aragon battalions, Tercio de los Almogávares later to become best known for its decimation during the battle of Belchite. Despite his age he served on the on and off basis in the frontline troops personally, suffering also combat wounds. From the onset he remained on good terms with the local Falange (to the growing anxiety of the Falangist leader, Manuel Hedilla, who fired the Zaragoza chief for too friendly relations with the Requetés). Faced with the forced amalgamation into the Francoist partido unico Comín theoretically complied, though he did his best to turn Aragon into a Carlist fiefdom very much like the neighboring Navarre. He was killed in a car accident in Zaragoza in March 1939.

Legacy

Though some members of the Comín dynasty of lawyers and scholars are currently acknowledged by various scientific institutions of the country, it is not the case of Jesús. He served as a point of reference for some works focusing on his son Alfonso Carlos (see Cambios en la identidad católica: La juventud de Alfonso Carlos Comín by Francisco J. Carmona Fernández). There is no mention of Jesús Comín on any of the official Carlist sites, be it this of the sixtinos, carloctavistas, CTC or Partido Carlista. There is a fairly substantial entry dedicated to Comín at the Gran Enciclopedia Aragonesa. Until 2009 there was a very short street commemorating him in Zaragoza. Its renaming was hailed in the local media as a revenge of democracy against Carlism. The author has claimed (probably correctly) that 99,9% of the passers-by had no idea who Jesús Comín was, but he still made the point that such a figure of "untold reactionary", a "Tejero of 1936", should be kept in oblivion.

See also

References

- Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil española, 1936-1939, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709758

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, London 1987, ISBN 978-0521086349, 0521086345

- Antonio Embid Idrujo, Ordenanzas y reglamentos municipales en el derecho español, Madrid 1978, ISBN 847088221X

- Francisco Gracia, Gabriela Sierra Cibiriain, Zaragoza en el Congreso de los Diputados. Parlamentarios durante la Segunda Republica, Zaragoza 2012, ISBN 9788499111636

- Pablo Larraz Andía, Víctor Sierra-Sesúmaga Ariznabarreta, Requetés: de las trincheras al olvido, Madrid 2011, ISBN 8499700462, 9788499700465

- Julian Sanz Hoya, De la resistencia a la reacción: las derechas frente a la Segunda República, Salamanca 2006, ISBN 8481024201

External links

- Comín's grandfather by Aragon Encyclopaedia

- Comín's uncle by Aragon Encyclopaedia

- Comín's father by Instituto Figuerola

- Sagues family explained

- Comín by Aragon Encyclopaedia

- Comin in Cuerpo earning 3,000 ptas

- Comín getting married

- Historical Index of Deputies

- Zaragoza deputies

- Comín clashing with Serrano in Cortes

- strength of Zaragoza requetes

- key 15 hours for Zaragoza during the Civil War

- Comín bringing 1200 requetes to Zaragoza

- Nationalist seizure of Zaragoza

- religious zeal in Zaragoza following its capture by the Nationalists

- Hedilla unhappy with the Falangists in Zaragoza

- Tercio de Nuestra Senora del Pilar; Carlist site

- Comín's wife obituary

- sample of Comín's daughter writing on women's fashion, 1973

- press obituary to Javier Comín Ros, 1995

- press homage to María Pilar Comín, 1997

- press celebrating Comín street being renamed, 2009

- Vizcainos! Por Dios y por España; contemporary Carlist propaganda