Jellium

Jellium, also known as the uniform electron gas (UEG) or homogeneous electron gas (HEG), is a quantum mechanical model of interacting electrons in a solid where the positive charges (i.e. atomic nuclei) are assumed to be uniformly distributed in space whence the electron density is a uniform quantity as well in space. This model allows one to focus on the effects in solids that occur due to the quantum nature of electrons and their mutual repulsive interactions (due to like charge) without explicit introduction of the atomic lattice and structure making up a real material. Jellium is often used in solid-state physics as a simple model of delocalized electrons in a metal, where it can qualitatively reproduce features of real metals such as screening, plasmons, Wigner crystallization and Friedel oscillations.

At zero temperature, the properties of jellium depend solely upon the constant electronic density. This lends it to a treatment within density functional theory; the formalism itself provides the basis for the local-density approximation to the exchange-correlation energy density functional.

The term jellium was coined by Conyers Herring, alluding to the "positive jelly" background, and the typical metallic behavior it displays.[1]

Hamiltonian

The jellium model treats the electron-electron coupling rigorously. The artificial and structureless background charge interacts electrostatically with itself and the electrons. The jellium Hamiltonian for N-electrons confined within a volume of space Ω, and with electronic density ρ(r) and background charge density n(R) = N/Ω is[2][3]

where

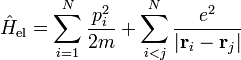

- Hel is the electronic Hamiltonian consisting of the kinetic and electron-electron repulsion terms:

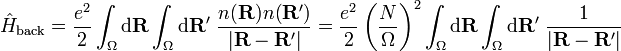

- Hback is the Hamiltonian of the positive background charge interacting electrostatically with itself:

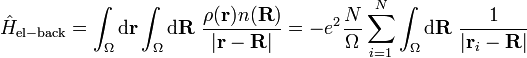

- Hel-back is the electron-background interaction Hamiltonian, again an electrostatic interaction:

Hback is a constant and, in the limit of an infinite volume, divergent along with Hel-back. The divergence is canceled by a term from the electron-electron coupling: the background interactions cancel and the system is dominated by the kinetic energy and coupling of the electrons. Such analysis is done in Fourier space; the interaction terms of the Hamiltonian which remain correspond to the Fourier expansion of the electron coupling for which q ≠ 0.

Contributions to the total energy

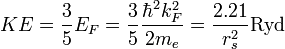

The traditional way to study the electron gas is to start with non-interacting electrons which are governed only by the kinetic energy part of the Hamiltonian, which yields the free electron gas model. The kinetic energy per electron is given by

where  is the Fermi energy,

is the Fermi energy,  is the Fermi wave vector, and the last expression shows the dependence on the Wigner-Seitz radius

is the Fermi wave vector, and the last expression shows the dependence on the Wigner-Seitz radius  where energy is measured in Rydbergs.

where energy is measured in Rydbergs.

Without doing much work, one can guess that the electron-electron interactions will scale like the inverse of the average electron-electron separation and hence as  (since the Coulomb interaction goes like one over distance between charges) so that if we view the interactions as a small correction to the kinetic energy, we are describing the limit of small

(since the Coulomb interaction goes like one over distance between charges) so that if we view the interactions as a small correction to the kinetic energy, we are describing the limit of small  (i.e.

(i.e.  being larger than

being larger than  ) and hence high electron density. Unfortunately, real metals typically have

) and hence high electron density. Unfortunately, real metals typically have  between 2-5 which means this picture needs serious revision.

between 2-5 which means this picture needs serious revision.

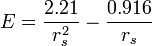

The first correction to the free-electron model for jelium is from the Fock exchange contribution to electron-electron interactions. Adding this in, one has a total energy of

where the negative term is due to exchange: exchange interactions lower the total energy. Higher order

corrections to the total energy are due to electron correlation and if one

decides to work in a series for small  , one finds

, one finds

The series is quite accurate for small  but of dubious value for

but of dubious value for  values found in actual metals.

values found in actual metals.

Applications

Jellium is the simplest model of interacting electrons. It is employed in the calculation of properties of metals, where the core electrons and the nuclei are modeled as the uniform positive background and the valence electrons are treated with full rigor. Semi-infinite jellium slabs are used to investigate surface properties such as work function and surface effects such as adsorption; near surfaces the electronic density varies in an oscillatory manner, decaying to a constant value in the bulk.[4][5][6]

Within density functional theory, jellium is used in the construction of the local-density approximation, which in turn is a component of more sophisticated exchange-correlation energy functionals. From quantum Monte Carlo calculations of jellium, accurate values of the correlation energy density have been obtained for several values of the electronic density,[7] which have been used to construct semi-empirical correlation functionals.[8]

The jellium model has been applied to superatoms, and used in nuclear physics.

See also

- Free electron model — a model electron gas where the electrons do not interact with anything.

- Nearly free electron model — a model electron gas where the electrons do not interact with each other, but do feel a (weak) potential from the atomic lattice.

References

- ↑ Hughes, R. I. G. (2006). "Theoretical Practice: the Bohm-Pines Quartet". Perspectives on Science 14 (4): 457–524. doi:10.1162/posc.2006.14.4.457.

- ↑ Gross, E. K. U.; Runge, E.; Heinonen, O. (1991). Many-Particle Theory. Bristol: Verlag Adam Hilger. pp. 79–80. ISBN 0-7503-0155-4.

- ↑ Giuliani, Gabriele; Vignale; Giovanni (2005). Quantum Theory of the Electron Liquid. Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-0-521-82112-4.

- ↑ Lang, N. D. (1969). "Self-consistent properties of the electron distribution at a metal surface". Solid State Commun. 7 (15): 1047–1050. Bibcode:1969SSCom...7.1047L. doi:10.1016/0038-1098(69)90467-0.

- ↑ Lang, N. D.; Kohn, W. (1970). "Theory of Metal Surfaces: Work Function". Phys. Rev. B 3 (4): 1215–223. Bibcode:1971PhRvB...3.1215L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.3.1215.

- ↑ Lang, N. D.; Kohn, W. (1973). "Surface-Dipole Barriers in Simple Metals". Phys. Rev. B 8 (12): 6010–6012. Bibcode:1973PhRvB...8.6010L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.8.6010.

- ↑ D. M. Ceperley and B. J. Alder (1980). "Ground State of the Electron Gas by a Stochastic Method". Phys. Rev. Lett. 45 (7): 566–569. Bibcode:1980PhRvL..45..566C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.45.566.

- ↑ Perdew, J. P.; McMullen, E. R.; Zunger, Alex (1981). "Density-functional theory of the correlation energy in atoms and ions: A simple analytic model and a challenge". Phys. Rev. A 23 (6): 2785–2789. Bibcode:1981PhRvA..23.2785P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.23.2785.