Janissaries

| Janissaries New Soldier | |

|---|---|

|

The Janissaries were chosen at about age six among the Christian boys, mostly Greeks, living in Anatolia and the Balkan peninsula to become the elite fighting force of the Ottoman Empire. A portion of these selected children, as they were considered to be more talented, received a higher standard of education to become the ruling class of viziers as well as engineers, architects, physicians and scientists. | |

| Active | 1363–1826 (1830 for Algier) |

| Allegiance |

|

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | 1,000 (1400),[1] 13,502 (1564),[2] 37,627 (1609),[2] 54,222 (1680)[2] |

| Headquarters | Adrianople (Edirne), Constantinople (Istanbul) |

| Colors | Blue, Red and Green |

| Engagements | Battle of Kosovo, Battle of Nicopolis, Battle of Ankara, Battle of Varna, Battle of Chaldiran, Battle of Mohács, Siege of Vienna, and others |

| Commanders | |

| First | Murad I |

| Last | Mahmud II |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| Military of the Ottoman Empire |

|

|

Classical Army (1451–1606) |

|

|

|

Modern army (1861–1922) |

|

Navy |

| Conscription |

The Janissaries (Ottoman Turkish: يڭيچرى yeniçeri, meaning "new soldier") were elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and bodyguards. Sultan Murad I created the force in 1383. The number of Janissaries grew from 20,000 in 1575, to 49,000 (1591), dropped to a low of 17,000 (1648), then rebounded to 135,000 in 1826.[3]

They began as an elite corps of slaves recruited from young Christian boys, and became famed for internal cohesion cemented by strict discipline and order. By 1620 they were hereditary and corrupt and an impediment to reform.[4] The corps was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 in the Auspicious Incident in which 6,000 or more were executed.[5]

Origins

Some historians such as Patrick Kinross date the formation of the Janissaries to around 1365, during the rule of Orhan's son Murad I, the first sultan of the Ottoman Empire.[6] The Janissaries became the first Ottoman standing army, replacing forces that mostly consisted of tribal warriors (ghazis) whose loyalty and morale were not always guaranteed.[6]

From the 1380s to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the devşirme system which was abolished in 1638.[7] This was the taking (enslaving) of non-Muslim boys,[8] notably Anatolian and Balkan Christians; Jews were never subject to devşirme, nor were children from Turkic families. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, "in early days, all Christians were enrolled indiscriminately. Later, those from Albania, Bosnia, and Bulgaria were preferred."[9] According to Dimitri Kitsikis, Christians from Northern Greece and Serbia were preferred.[10]

The Janissaries were kapıkulları (sing. kapıkulu), "door servants" or "slaves of the Porte", neither freemen nor ordinary slaves (köle).[11] They were subjected to strict discipline, but were paid salaries and pensions upon retirement and formed their own distinctive social class.[12] As such, they became one of the ruling classes of the Ottoman Empire, rivaling the Turkish aristocracy. The brightest of the Janissaries were sent to the palace institution, Enderun. Through a system of meritocracy, the Janissaries held enormous power, stopping all efforts at reform of the military.[7]

According to military historian Michael Antonucci and economic historians Glenn Hubbard and Tim Kane, the Turkish administrators would scour their regions (but especially the Balkans) every five years for the strongest sons of the sultan's Christian subjects. These boys (usually between the ages of 6 and 14) were then taken from their parents and given to Turkish families in the provinces to learn Turkish language and customs, and the rules of Islam. The recruits were indoctrinated into Islam, forced into circumcision and supervised 24 hours a day by eunuchs. They were subjected to severe discipline, being prohibited from growing a beard, taking up a skill other than soldiering, and marrying. As a result, the Janissaries were extremely well-disciplined troops, and became members of the askeri class, the first-class citizens or military class. Most were non-Muslims, because it was not permissible to enslave a Muslim.[7]

The Janissary system was introduced in the 14th century. It was a similar system to the Iranian Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar era ghulams, who were drawn from converted Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians, and in the same way as with the Ottoman's Janissaries who had to replace the unreliable ghazis, they were initially created as a counterbalance to the tribal, ethnic and favoured interests the Qizilbash gave, which make a system imbalanced.[13] The Janissary Corps was a trained and loyal group of slaves to the sultan. In the late 16th century, a sultan gave in to the pressures of the Corps and permitted Janissary children to become members of the Corps, a practice strictly forbidden for the previous 300 years. They also became rent-seeking and sought protection of their special rights and advantages. According to paintings of the era, they were also permitted to grow beards. Consequently, the formerly strict rules of succession became open to interpretation. While they advanced their own power, the Janissaries also helped to keep the system from changing in other progressive ways and according to some scholars the corps was most responsible for the political stagnation of Istanbul.[14]

Greek Historian Dimitri Kitsikis in his book Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu ("Turco-Greek Empire")[10] states that many Christian families were willing to comply with the devşirme because it offered a possibility of social advancement. Conscripts could one day become Janissary colonels, statesmen who might one day return to their home region as governors, or even Grand Viziers or Beylerbeys (governor generals).

Some of the most famous Janissaries include George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, an Albanian who defected and led a 20‑year Albanian revolt against the Ottomans. Another was Sokollu Mehmed Paşa, a Bosnian Serb who became a grand vizier, served three sultans, and was the de facto ruler of the Ottoman Empire for more than 14 years.[15]

Characteristics

The Janissary corps were distinctive in a number of ways. They wore unique uniforms, were paid regular salaries for their service, marched to music (the mehter), lived in barracks and were the first corps to make extensive use of firearms. A Janissary battalion was a close-knit community, effectively the soldier's family. By tradition, the Sultan himself, after authorizing the payments to the Janissaries, visited the barracks dressed as a Janissary trooper, and received his pay alongside the other men of the First Division.[17] They also served as policemen, palace guards, and firefighters during peacetime.[18] The Janissaries also enjoyed far better support on campaign than other armies of the time. They were part of a well-organized military machine, in which one support corps prepared the roads while others pitched tents and baked the bread. Their weapons and ammunition were transported and re-supplied by the cebeci corps. They campaigned with their own medical teams of Muslim and Jewish surgeons and their sick and wounded were evacuated to dedicated mobile hospitals set up behind the lines.[17]

These differences, along with an impressive war-record, made the Janissaries a subject of interest and study by foreigners during their own time. Although eventually the concept of a modern army incorporated and surpassed most of the distinctions of the Janissaries and the corps was eventually dissolved, the image of the Janissary has remained as one of the symbols of the Ottomans in the western psyche. By the mid-18th century they had taken up many trades and gained the right to marry and enroll their children in the corps and very few continued to live in the barracks.[18] Many of them became administrators and scholars. Retired or discharged Janissaries received pensions, and their children were also looked after. This evolution away from their original military vocation was the major cause of the system's demise.

Recruitment, training and status

The first Janissary units were formed from prisoners of war and slaves, probably as a result of the sultan taking his traditional one-fifth share of his army's plunder in kind rather than cash; however the continuing enslaving of dhimmi constituted a continuing abuse of a subject population.[20] Initially the recruiters favoured Greeks and Albanians. As borders of the Ottoman Empire expanded, the devşirme was extended to include Bulgarians, Croats, Serbs, Armenians and later, in rare instances, Romanians, Georgians, Poles, Ukrainians and southern Russians. The Janissaries first began enrolling outside the devşirme (known as blood tax) system during the reign of Sultan Murad III (1574–1595).

After this period, volunteers were enrolled, mostly of Turkish origin.[17] By 1683, Sultan Mehmet IV abolished the devşirme, as increasing numbers of originally Muslim Turkish families had already enrolled their own sons into the force hoping for a lucrative career.[17]

The prescribed daily rate of pay for entry-level Janissaries in the time of Ahmet I was three Akçes. Promotion to a cavalry regiment implied a minimum salary of 10 Akçes.[21] Janissaries received a sum of 12 Akçes every three months for clothing incidentals and 30 Akçes for weaponry with an additional allowance for ammunition as well.[22]

Training

When a non-Muslim boy was recruited under the devşirme system, he would first be sent to selected Turkish families in the provinces to learn how to speak Turkish, the rules of Islam (i.e. to be converted to Islam) and the customs and cultures of Ottoman society. After completion of this period, acemi (rookie) boys would be gathered to be trained in Enderun "acemi oğlan" school at the capital city. At the school, young cadets would be selected for their talents in different areas to train as engineers, artisans, riflemen, clerics, archers, artillery, and so forth. Janissaries trained under strict discipline with hard labour and in practically monastic conditions in acemi oğlan ("rookie" or "cadet") schools, where they were expected to remain celibate. Unlike other Muslims, they were expressly forbidden to wear beards, only a moustache. These rules were obeyed by Janissaries, at least until the 18th century when they also began to engage in other crafts and trades, breaking another of the original rules. In the late 16th century a sultan gave in to the pressures of the Janissary Corps and permitted Janissary children to become members of the Corps, a practice strictly forbidden for 300 years. They also became rent-seeking and made goals to protect their special rights and advantages. Consequently succession rules, formerly strict, became open to interpretation. They gained their own power but kept the system from changing in other progressive ways.[14]

For all practical purposes Janissaries belonged to the Sultan and they were regarded as the protectors of the throne and the Sultan. Janissaries were taught to consider the corps as their home and family, and the Sultan as their father. Only those who proved strong enough earned the rank of true Janissary at the age of 24 or 25. The Ocak inherited the property of dead Janissaries, thus acquiring wealth. Janissaries also learned to follow the dictates of the dervish saint Haji Bektash Veli, disciples of whom had blessed the first troops. Bektashi served as a kind of chaplain for Janissaries. In this and in their secluded life, Janissaries resembled Christian military orders like the Knights Hospitaller. As a symbol of their devotion to the order, Janissaries wore special hats called "börk". These hats also had a holding place in front, called the "kaşıklık", for a spoon. This symbolized the "kaşık kardeşliği", or the "brotherhood of the spoon", which reflected a sense of comradeship among the Janissaries who ate, slept, fought and died together.[7]

Janissary corps

The corps was organized in ortas. An orta (equivalent to a battalion) was headed by a çorbaci. All ortas together comprised the Janissary corps proper and its organization, named ocak (literally "hearth"). Suleiman I had 165 ortas and the number increased over time to 196. While the Sultan was the supreme commander of the Ottoman Army and of the Janissaries in particular, the corps was organized and led by a commander, the ağa. The corps was divided into three sub-corps:

- the cemaat (frontier troops; also spelled jemaat), with 101 ortas

- the beyliks or beuluks (the Sultan's own bodyguard), with 61 ortas

- the sekban or seirnen, with 34 ortas

In addition there were also 34 ortas of the ajemi (cadets). A semi-autonomous Janissary corps was permanently based in Algiers.

Originally Janissaries could be promoted only through seniority and within their own orta. They could leave the unit only to assume command of another. Only Janissaries' own commanding officers could punish them. The rank names were based on positions in the kitchen staff or the royal hunters, perhaps to emphasise that Janissaries were servants of the Sultan. Local Janissaries, stationed in a town or city for a long time, were known as yerliyyas.

Corps strength

Even though the Janissaries were part of the royal army and personal guards of the sultan, the corps was not the main force of the Ottoman military. In the classical period, Janissaries were only one tenth of the overall Ottoman army, while the traditional Turkish cavalry made up the rest of the main battle force. According to David Nicolle, the number of Janissaries in the 14th century was 1,000 and about 6,000 in 1475. The same source estimates the number of Timarli Sipahi, the provincial cavalry which constituted the main force of the army at 40,000.[1]

Documentation from the 1620s and 1630s recording troop mobilization levels for two middle sized campaigns suggest that at a time when full Janissary membership in the Istanbul barracks amounted to some 30,000 men those actually deployed at the front ranged between 20,000 and 25,000.[23]

A roll call held in Hungary in 1541, reflecting the actual deployed strength of the Ottoman regular army forces participating in campaign, registered 15,612 men as present. Of these approximately 6,350 were Janissaries, 3,700 were Sipahis and another 1,650 were members of the Artillery corps. The remaining one quarter (roughly 4,100 men) were mostly non-combatatants. Information for the year 1660 when the only active front was in Transylvania (siege of Varat/Oradea in July/August) indicates 18,013 actives out of a total Janissary enrollment of 32,794. It does not follow from the fact that 18,000 Janissaries were present for salary distributions in the field that even they took a very active role in the fighting.[24]

| Year | 1400 | 1514 | 1523 | 1526 | 1564 | 1567–68 | 1574 | 1603 | 1609 | 1660–61 | 1665 | 1669 | 1670 | 1680 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strength | <1,000[1] | 10,156[2] | 12,000[2] | 7,885[2] | 13,502[2] | 12,798[2] | 13,599[2] | 14,000[2] | 37,627[2] | 54,222[2] | 49,556[2] | 51,437[2] | 49,868[2] | 54,222[2] |

Equipment

During the initial period of formation, Janissaries were expert archers, but they began adopting firearms as soon as such became available during the 1440s. The siege of Vienna in 1529 confirmed the reputation of their engineers, e.g. sappers and miners. In melee combat they used axes and kilijs. Originally in peacetime they could carry only clubs or daggers, unless they served as border troops. Turkish yatagan swords were the signature weapon of the Janissaries, almost a symbol of the corps. Janissaries who guarded the palace (Zülüflü Baltacılar) carried long-shafted axes and halberds.

By the early 16th century, the Janissaries were equipped with and were skilled with muskets.[25] In particular, they used a massive "trench gun", firing an 80-millimetre (3.1 in) ball, which was "feared by their enemies".[25] Janissaries also made extensive use of early grenades and hand cannons, such as the abus gun.[17] Pistols were not initially popular but they became so after the Cretan War (1645–1669).[26]

Battles

The Ottoman Empire used Janissaries in all its major campaigns, including the 1453 capture of Constantinople, the defeat of the Egyptian Mamluks and wars against Hungary and Austria. Janissary troops were always led to the battle by the Sultan himself, and always had a share of the loot. The Janissary corps was the only infantry division of the Ottoman army. In battle the Janissaries' main mission was to protect the Sultan, using cannon and smaller firearms, and holding the center of the army against enemy attack during the strategic fake forfeit of Turkish cavalry. The Janissary corps also included smaller expert teams: explosive experts, engineers and technicians, sharpshooters (with arrow and rifle) and sappers who dug tunnels under fortresses, etc.

-

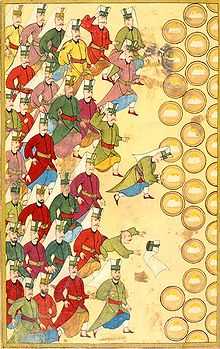

Janissaries battling the Knights Hospitaller during the Siege of Rhodes in 1522.

-

Battle of Mohács, 1526.[1]

-

A Janissary, a pasha and cannon batteries at the Siege of Esztergom in 1543.

- ^ Lokman (1588). "Battle of Mohács (1526)". Hünernâme.

- ^ Osman, Nakkas (1597). "Expedition to Revan". Shahin-Shah-nama, Topkapi Sarai Museum, Ms B.200, folio 102a.

The Decline of the Janissaries

The Janissaries were once a valiant military force for the Ottoman Empire, but by the 18th century that was not the case. The reason for this was because their discipline had decreased because the Janissaries had grown accustomed to a civilian life. Instead of being a full-time standing army whose only job was to train, the Janissaries began engaging in business and having families. These non-military activities and privileges made them less inclined towards combat. As a result, the military might of the Ottoman Empire began to decline.

Revolts and disbandment

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny and dictate policy and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. They could change Sultans as they wished through palace coups. They made themselves landholders and tradesmen. They would also limit the enlistment to the sons of former Janissaries who did not have to go through the original training period in the acemi oğlan, as well as avoiding the physical selection, thereby reducing their military value. When Janissaries could practically extort money from the Sultan and business and family life replaced martial fervour, their effectiveness as combat troops decreased. The northern borders of the Ottoman Empire slowly began to shrink southwards after the second Battle of Vienna in 1683.

In 1449 they revolted for the first time, demanding higher wages, which they obtained. The stage was set for a decadent evolution, like that of the Streltsy of Tsar Peter's Russia or that of the Praetorian Guard which proved the greatest threat to Roman emperors, rather than an effective protection. After 1451, every new Sultan felt obligated to pay each Janissary a reward and raise his pay rank (although since early Ottoman times, every other member of the Topkapi court received a pay raise as well). Sultan Selim II gave Janissaries permission to marry in 1566, undermining the exclusivity of loyalty to the dynasty. By 1622, the Janissaries were a "serious threat" to the stability of the Empire.[27] Through their "greed and indiscipline", they were now a law unto themselves and, against modern European armies, ineffective on the battlefield as a fighting force.[27] In 1622, the teenage Sultan Osman II, after a defeat during war against Poland, determined to curb Janissary excesses and outraged at becoming "subject to his own slaves" tried to disband the Janissary corps blaming it for the disaster during the Polish war.[27] In the spring, hearing rumours that the Sultan was preparing to move against them, the Janissaries revolted and took the Sultan captive, imprisoning him in the notorious Seven Towers: he was murdered shortly afterwards.[27]

In 1804, the Dahias, the Jannisary junta that ruled Serbia at the time, had taken power in the Sanjak of Smederevo in defiance of the Sultan and they feared that the Sultan would make use of the Serbs to oust them. To forestall this they decided to execute all prominent nobles throughout Central Serbia, a move known as Slaughter of the knezes. According to historical sources of the city of Valjevo, heads of the murdered men were put on public display in the central square to serve as an example to those who might plot against the rule of the Janissaries. The event triggered the start of the Serbian revolution with the First Serbian uprising aimed at putting an end to the 300 years of Ottoman occupation of modern Serbia.[28]

In 1807 a Janissary revolt deposed Sultan Selim III, who had tried to modernize the army along Western European lines.[29] This modern army Selim III created was called Nizam-ı Cedid. His supporters failed to recapture power before Mustafa IV had him killed, but elevated Mahmud II to the throne in 1808.[29] The Janissaries killed Selim III based off their own accusations that the Sultan failed respect the religion of Islam. When the Janissaries threatened to oust Mahmud II, he had the captured Mustafa executed and eventually came to a compromise with the Janissaries.[29] Ever mindful of the Janissary threat, the sultan spent the next years discreetly securing his position. The Janissaries' abuse of power, military ineffectiveness, resistance to reform and the cost of salaries to 135,000 men, many of whom were not actually serving soldiers, had all become intolerable.[30]

By 1826, the sultan was ready to move against the Janissary in favor of a more modern military. Historian Patrick Kinross suggests that Mahmud II incited them to revolt on purpose, describing it as the sultan's "coup against the Janissaries".[5] The sultan informed them, through a fatwa, that he was forming a new army, organised and trained along modern European lines.[5] As predicted, they mutinied, advancing on the sultan's palace.[5] In the ensuing fight, the Janissary barracks were set in flames by artillery fire resulting in 4,000 Janissary fatalities.[5] The survivors were either exiled or executed, and their possessions were confiscated by the Sultan.[5] This event is now called the Auspicious Incident. The last of the Janissaries were then put to death by decapitation in what was later called the blood tower, in Thessaloniki.

Janissary music

The military music of the Janissaries was noted for its powerful percussion and shrill winds combining kös (giant timpani), davul (bass drum), zurna (a loud shawm), naffir, or boru (natural trumpet), çevgan bells, triangle, (a borrowing from Europe), and cymbals (zil), among others. Janissary music influenced European classical musicians such as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven, both of whom composed music in the "Alla turca" style (Mozart's Piano Sonata in A major, K. 331 (c. 1783), Beethoven's incidental music for The Ruins of Athens, Op. 113 (1811), and the final movement of Symphony no. 9), although the Beethoven example is now considered a march rather than Alla turca.[31]

Sultan Mahmud II abolished the mehter band in 1826 along with the Janissary corps. Mahmud replaced the mehter band in 1828 with a European style military band trained by Giuseppe Donizetti. In modern times, although the Janissary corps no longer exists as a professional fighting force, the tradition of Mehter music is carried on as a cultural and tourist attraction.

In 1952, the Janissary military band, Mehterân, was organized again under the auspices of the Istanbul Military Museum. They have performances during some national holidays as well as in some parades during days of historical importance. For more details, see Turkish music (style) and Mehter.

Popular culture

- Nowadays in Bulgaria the word Janissar is used as a synonym of the word traitor.

- Janissaries appear in many video games such as: Europa Universalis IV, Atlantica Online, Assassin's Creed: Revelations, Rise of Nations, Empire Earth 2, Civilization IV: Beyond the Sword, Civilization V, Age of Empires 2: The Age of Kings, Age of Empires II: The Conquerors, Age of Empires 3, Medieval II: Total War, Empire: Total War and Napoleon: Total War.

- The Janissary Tree, a novel by Jason Goodwin set in 19th-century Istanbul

- The Sultan's Helmsman, a historical novel of the Ottoman Navy and Renaissance Italy

- The Historian, a novel by Elizabeth Kostova

- "The Janissaries of Emilion", a short story by Basil Copper

- Janissaries are used to introduce the character of Eliza in The King of the Vagabonds, the second volume of Quicksilver by Neal Stephenson.

- The Janissary origin as an elite fighting corps trained from boy slaves is a central plot element in the film, Dracula Untold.

- The Janissaries are referenced in The Reluctant Fundamentalist as a point of comparison for the main character Changez, a Lahori working as an analyst for Underwood Samson in New York.

See also

- Devşirme system

- Ghilman

- Mamluk

- Military of the Ottoman Empire

- Saqaliba

- Genízaro

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Nicolle, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Agoston, p. 50

- ↑ George F. Nafziger (2001). Historical Dictionary of the Napoleonic Era. Scarecrow Press. pp. 153–54.

- ↑ Alan Palmer, The Decline and Fall of the Ottoman Empire (1992) pp 23, 92–93

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Kinross, pp. 456–457.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Kinross, pp 48–52.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Hubbard, Glenn and Tim Kane. (2013) (2013). Balance: The Economics of Great Powers From Ancient Rome to Modern America. Simon & Schuster. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-1-4767-0025-0.

- ↑ Perry Anderson. Lineages of the Absolutist State (Verso, 1974), p. 366.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. Eleventh Edition, vol. 15, p 151.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Kitsikis, Dimitri (1996). Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu. Istanbul,Simurg Kitabevi

- ↑ Shaw, Stanford; Ezel Kural Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-521-21280-4.

- ↑ Zürcher, Erik (1999). Arming the State. United States of America: LB Tauris and Co Ltd. pp. 5. ISBN 1-86064-404-X.

- ↑ "BARDA and BARDA-DĀRI v. Military slavery in Islamic Iran". Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hubbard, Glenn and Tim Kane (2013). Balance: The Economics of Great Powers From Ancient Rome to Modern America. Simon & Schuster. p. 153. ISBN 978-1-4767-0025-0.

- ↑ Imamović, Mustafa (1996). Historija Bošnjaka. Sarajevo: BZK Preporod. ISBN 9958-815-00-1

- ↑ Nasuh, Matrakci (1588). "Janissary Recruitment in the Balkans". Süleymanname, Topkapi Sarai Museum, Ms Hazine 1517.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Uzunçarşılı, pp 66–67, 376–377, 405–406, 411–463, 482–483

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goodwin. J, pp. 59, 179–181

- ↑ The Janissaries and the Ottoman Armed forces

- ↑ Nicolle, p. 7.

- ↑ Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p. 225

- ↑ Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p. 234

- ↑ Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, p. 46

- ↑ Ottoman Warfare 1500–1700, Rhoads Murphey, 1999, pp. 46–47

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Nicolle, p. 36.

- ↑ Nicolle, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 Kinross, pp. 292–295

- ↑ History of Servia and the Servian Revolution-Leopold von Ranke,tran:Louisa Hay Ker p 119–20

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Kinross, pp 431–434.

- ↑ Levy, Avigdor. "The Ottoman Ulama and the Military Reforms of Sultan Mahmud II." Asian and African Studies 7 (1971): 13–39.

- ↑ See "Janissary music," New Grove Online

Bibliography

- Aksan, Virginia H. "Whatever Happened to the Janissaries? Mobilization for the 1768-1774 Russo-Ottoman War." War in History (1998) 5#1 pp: 23-36. online

- Cleveland, William L. A History of the Modern Middle East (Boulder: Westview, 2004)

- Agoston, Gabor. Barut, Top ve Tüfek Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun Asker Gücü ve Silah Sanayisi, ISBN 975-6051-41-8.

- Goodwin, Godfrey (2001). The Janissaries. UK: Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0-86356-055-2; anecdotal and not scholarly says Aksan (1998)

- Goodwin, Jason (1998). Lords of the Horizons: A History of the Ottoman Empire. New York: H. Holt ISBN 0-8050-4081-1

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983). History of the Balkans, 18th and 19th Centuries. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27458-3

- Kinross, Patrick (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire London: Perennial. ISBN 978-0-688-08093-8

- Kitsikis,Dimitri, (1985, 1991, 1994). L'Empire ottoman. Paris,: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-043459-2

- Nicolle, David (1995). The Janissaries. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-413-8

- Pallis, Alexander. In the Days of the Janissaries (Hutchinson, 1951); based on a travel account

- Palmer, J. A. B. The origin of the Janissaries (Manchester University Press, 1953)

- Shaw, Stanford J. (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Vol. I). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29163-7

- Shaw, Stanford J. & Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Vol. II). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29166-8

- Uzunçarşılı, İsmail (1988). Osmanlı Devleti Teşkilatından Kapıkulu Ocakları: Acemi Ocağı ve Yeniçeri Ocağı. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu. ISBN 975-16-0056-1

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Janissaries. |

- History of the Janissary Music

- Janissary section on German-language website about Ottomman empire (not yet exploited) (German)

-

"Janizaries". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Janizaries". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.