Jain philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

Jain Prayers |

|

Major figures |

|

Major Sects |

|

Festivals |

| Jainism portal |

Jain philosophy deals with metaphysics, reality, cosmology, ontology, epistemology and divinity. Jainism is a transtheistic religion of ancient India. The distinguishing features of Jain philosophy are its belief on independent existence of soul and matter, absence of a supreme divine creator, owner, preserver or destroyer, potency of karma, eternal and uncreated universe, a strong emphasis on non-violence, accent on relativity and multiple facets of truth, and morality and ethics based on liberation of soul. Jain philosophy attempts to explain the rationale of being and existence, the nature of the Universe and its constituents, the nature of bondage and the means to achieve liberation.

Jainism has often been described as an ascetic movement for its strong emphasis on self-control, austerities and renunciation. It has also been called a model of philosophical liberalism for its insistence that truth is relative and multifaceted and for its willingness to accommodate all possible view-points of the rival philosophies. It strongly upholds the individualistic nature of soul and personal responsibility for one's decisions; and that self-reliance and individual efforts alone are responsible for one's liberation.

Throughout its history, the Jain philosophy remained unified and single, although as a religion, Jainism was divided into various sects and traditions. The contribution of Jain philosophy in developing some Indian philosophies has been significant. Jain philosophical concepts like Ahimsa, Karma, Moksa, Samsara and like have been assimilated into the philosophies of other Indian religions like Hinduism and Buddhism in various forms. While Jainism traces its philosophy from teachings of tirthankara, various Jain philosophers from Kundakunda and Umaswati in ancient times to Yaśovijaya in recent times have contributed greatly in developing and refining the Jain and Indian philosophical concepts.

Metaphysics

Ontology

There are infinite independent souls. These are categorised into two—liberated and non-liberated. Infinite knowledge, perception and bliss are the intrinsic qualities of a soul.[1] These qualities are fully enjoyed unhindered by liberated souls, but obscured by karma in the case of non-liberated souls resulting in karmic bondage. This bondage further results in a continuous co-habitation of the soul with the body. Thus, an embodied non-liberated soul is found in four realms of existence—heavens, hells, humans and animal world – in a never-ending cycle of births and deaths also known as samsāra. The soul is in bondage since beginningless time; however, it is possible to achieve liberation through rational perception, rational knowledge and rational conduct. Harry Oldmeadow notes that Jain ontology is both realist and dualist metaphysics.[2] It is realist in the sense that knowledge of ultimate reality does not exclude the reality of the existing world; the enlightened worldview includes the knowledge of particulars and the world continues to be real even after the liberation. It is dualist in that the two prime categories of substance, soul and matter, are mutually exclusive.

Jain metaphysics is based on seven (sometimes nine, with subcategories) truths or fundamental principles also known as tattva, which are an attempt to explain the nature and solution to the human predicament.[3]

Dravya

This Universe is made up of what Jains call the six dravyas or substances which are the basic constituents of reality and are classified as follows:[4]

- Jīva (The living substances) : Jains believe that souls (Jīva) exist as a reality, having a separate existence from the body that houses it. Jīva is characterised by cetana (consciousness) and upayoga (knowledge and perception). Though the soul experiences both birth and death, it is neither really destroyed nor created. Decay and origin refer respectively to the disappearing of one state of soul and appearance of another state, these being merely the modes of the soul.

- Ajīva (Non-Living Substances)

- Pudgala – It is non living (no soul) Matter, which is classified as solid, liquid, gaseous, energy, fine Karmic materials and extra-fine matter or ultimate particles. Paramānu or ultimate particles are the basic building block of matter. One of the qualities of the Paramānu and Pudgala is that of permanence and indestructibility. It combines and changes its modes but its basic qualities remain the same. According to Jainism, it cannot be created nor destroyed.

- Dharmatattva – (Medium of Motion) and Adharmatattva (Medium of Rest) – Also known as Dharmāstikāya and Adharmāstikāya, they are unique to Jain thought depicting the principles of motion and rest. They are said to pervade the entire universe. Dharma-tattva and Adharma-tattva are by themselves not motion or rest but mediate motion and rest in other bodies. Without dharmāstikāya motion is not possible and without adharmāstikāya rest is not possible in the universe.

- Ākāśa: Space – Space is a substance that accommodates souls, matter, the principle of motion, the principle of rest, and time. It is all-pervading, infinite and made of infinite space-points.

- Kāla Time is a real entity according to Jainism and activities, changes or modifications can be achieved only through time. In Jainism, the time is likened to a wheel with twelve spokes divided into descending and ascending halves with six stages, each of immense duration estimated at billions of sagaropama (ocean years).[5] According to Jains, sorrow increases at each progressive descending stage and happiness and bliss increase in each progressive ascending stage.

These are the uncreated existing constituents of the Universe which impart the necessary dynamics to the Universe by interacting with each other. These constituents behave according to the natural laws and their nature without interference from external entities. Dharma or true religion according to Jainism is Vatthu sahāvō dhammō translated as "the intrinsic nature of a substance is its true religion."

Karma

In Jainism, karma is the basic principle within an overarching psycho-cosmology. It not only encompasses the causality of transmigration, but is also conceived of as an extremely subtle matter, which infiltrates the soul—obscuring its natural, transparent and pure qualities. Karma is thought of as a kind of pollution, that taints the soul with various colours (leśyā).[6] Based on its karma, a soul undergoes transmigration and reincarnates in various states of existence—like heavens or hells, or as humans or animals.

Jains cite inequalities, sufferings, and pain as evidence for the existence of karma. Jain texts have classified the various types of karma according to their effects on the potency of the soul. The Jain theory seeks to explain the karmic process by specifying the various causes of karmic influx (āsrava) and bondage (bandha), placing equal emphasis on deeds themselves, and the intentions behind those deeds.[7] The Jain karmic theory attaches great responsibility to individual actions, and eliminates reliance on supposed existence of divine grace or retribution.[8] The Jain doctrine also holds that it is possible for us to both modify our karma, and to obtain release from it, through the austerities and purity of conduct.

Cosmology

Jain cosmology denies the existence of a supreme being responsible for creation and operation of universe. According to Jainism, this loka or Universe is an uncreated entity, existing since infinity, immutable in nature, beginningless and endless. Jain texts describe the shape of the Universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arm resting on his waist. The Universe according to Jainism is narrow at top and broad at middle and once again becomes narrow at the bottom. Mahāpurāṇa of Ācārya Jinasena is famous for his quote:[9]

Some foolish men declare that the creator made the world. The doctrine that the world was created is ill advised and should be rejected. If god created the world, where was he before the creation? If you say he was transcendent then and needed no support, where is he now? How could god have made this world without any raw material? If you say that he made this first, and then the world, you are faced with an endless regression.

Kalchakra

According to Jainism, time is beginningless and eternal. The Kālacakra, the cosmic wheel of time, rotates ceaselessly.[10] The wheel of time is divided into two half-rotations, Utsarpiṇī or ascending time cycle and Avasarpiṇī, the descending time cycle, occurring continuously after each other. Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity and happiness, while Avsarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality. Each of this half time cycle consisting of innumerable period of time (measured in Sagaropama and Palyopama years) is further sub-divided into six aras or epochs of unequal periods. Currently, the time cycle is in avasarpiṇī or descending phase with the following epochs.[11] The aras defined in Jain texts are:

- Suṣama-suṣamā

- Suṣamā

- Suṣama-duḥṣamā

- Duḥṣama-suṣamā

- Duḥṣama

- Duḥṣama-duḥṣama

In utsarpiṇī the order of the aras is reversed. Starting from Duḥṣama- duḥṣamā, it ends with Suṣama-suṣamā and thus this never ending cycle continues.[12] Each of these aras progress into the next phase seamlessly without apocalyptic consequences. The increase or decrease in the happiness, life spans and length of people and general moral conduct of the society changes in a phased and graded manner as the time passes. No divine or supernatural beings are credited or responsible with these spontaneous temporal changes, either in a creative or overseeing role, rather human beings and creatures are born under the impulse of their own karma.[13]

Loka

The early Jains contemplated the nature of the earth and universe and developed a detailed hypothesis on the various aspects of astronomy and cosmology. According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into 3 parts:[14]

- Urdhva Loka – the realms of the gods or heavens

- Madhya Loka – the realms of the humans, animals and plants

- Adho Loka – the realms of the hellish beings or the infernal regions

Urdhva Loka

Upper World (Udharva loka) is divided into different abodes and are the realms of the heavenly beings who are non-liberated souls.[15] Upper World is divided into sixteen Devalokas, nine Graiveyaka, nine Anudish and five Anuttar abodes. Sixteen Devaloka abodes are Saudharma, Aishana, Sanatkumara, Mahendra, Brahma, Brahmottara, Lantava, Kapishta, Shukra, Mahashukra, Shatara, Sahasrara, Anata, Pranata, Arana and Achyuta.[15] Nine Graiveyak abodes are Sudarshan, Amogh, Suprabuddha, Yashodhar, Subhadra, Suvishal, Sumanas, Saumanas and Pritikar. Nine Anudish are Aditya, Archi, Archimalini, Vair, Vairochan, Saum, Saumrup, Ark and Sphatik. Five Anuttar are Vijaya, Vaijayanta, Jayanta, Aparajita and Sarvarthasiddhi.[15] The sixteen heavens in Devalokas are also called Kalpas and the rest are called Kalpatit. Those living in Kalpatit are called Ahamindra and are equal in grandeur. There is increase with regard to the lifetime, influence of power, happiness, lumination of body, purity in thought-colouration, capacity of the senses and range of clairvoyance in the Heavenly beings residing in the higher abodes.[15] But there is decrease with regard to motion, stature, attachment and pride. The higher groups, dwelling in 9 Greveyak and 5 Anutar Viman. They are independent and dwelling in their own vehicles. The anuttara souls attain liberation within one or two lifetimes. The lower groups, organised like earthly kingdoms – rulers (Indra), counselors, guards, queens, followers, armies etc.[15] Above the Anutar vimans, at the apex of the universe, is the Siddhasila, the realms of the liberated souls also known as the Siddhas, the perfected omniscient and blissful beings, who are venerated by the Jains.[16]

Madhya Loka

Madhya Loka, at the centre of the universe consists of 900 yojans above and 900 yojans below earth surface. It is inhabited by jyotishka deva, human, tiryanch and vyantar deva. It consists of continent-islands surrounded by oceans. Some of these continents and oceans are Jambudvipa, Lavanoda, Ghatki Khand, Kaloda, Puskarvardvīpa, Puskaroda, Varunvardvīpa, Varunoda, Kshirvardvīpa, Kshiroda, Ghrutvardvīpa, Ghrutoda, Ikshuvardvīpa, Iksuvaroda, Nandishwardvīpa and Nandishwaroda.[17] Mount Meru is at the centre of the world surrounded by Jambūdvīpa, in form of a circle.[16] There are two sets of sun, moon and stars revolving around Mount Meru; while one set works, the other set rests behind the Mount Meru.[18] Jambūdvīpa has 6 mighty mountains, dividing the continent into 7 zones (Ksetra). The names of these zones are Bharat kshetra, Mahavideh kshetra, Airavat kshetra, Ramyak, Hairanyvat kshetra, Haimava kshetra, Hari kshetra. The three zones Bharat kshetra, Mahavideh kshetra and Airavat kshetra are also known as Karma bhoomi because practice of austerities and liberation is possible and the Tirthankaras preach the Jain doctrine.[17] The other four zones, Ramyak, Hairanyvat Kshetra, Haimava Kshetra and Hari Kshetra are known as akarmabhoomi or bhogbhumi as humans live a sinless life of pleasure and no religion or liberation is possible.

Adho Loka

The lower world consists of seven hells which is inhabited by Bhavanpati demigods and the hellish beings. Hellish beings reside in hells whose names are Ratna prabha-dharma, Sharkara prabha-vansha, Valuka prabha-megha, Pank prabha-anjana, Dhum prabha-arista, Tamah prabha-maghavi, Mahatamah prabha-maadhavi.[19]

Śalākāpuruṣas

During the each motion of the half-cycle of the wheel of time, 63 Śalākāpuruṣa or 63 illustrious men, consisting of the 24 Tīrthaṅkaras and their contemporaries regularly appear. The Jain universal or legendary history is basically a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious men. They are 24 Tīrthaṅkara, 12 Chakravartī, 9 Baladevas, 9 Vāsudevas and 9 Prativāsudevas. Besides these there are 9 Narada, 11 Rudras, 24 Kamdeva, 24 Fathers of the Tirthankaras, 24 Mothers of the Tirthankaras and 14 Kulakaras who are also important figures in Jain universal history.

Epistemology

Jainism made its own unique contribution to this mainstream development of philosophy by occupying itself with the basic epistemological issues, namely, with those concerning the nature of knowledge, how knowledge is derived, and in what way knowledge can be said to be reliable. Knowledge for the Jains takes place in the soul, which, without the limiting factor of karma, is omniscient. Humans have partial knowledge – the object of knowledge is known partially and the means of knowledge do not operate to their full capacity. According to Tattvārthasūtra, the knowledge of the basic Jaina truths can be obtained through:

- Pramāṇa – means or instruments of knowledge which can yield a comprehensive knowledge of an object, and

- Naya – particular standpoints, yielding partial knowledge.

Pramāṇa are of five kinds:[20]

- mati or "sensory knowledge",

- Sruta or "scriptural knowledge",

- avadhi or "clairvoyance",

- manahparyaya or "telepathy", and

- kevala” or "omniscience"

The first two are described as being indirect means of knowledge (parokṣa), with the others furnishing direct knowledge (pratyakṣa), by which it is meant that the object is known directly by the soul. Jains came out with their doctrines of relativity used for logic and reasoning:

- Anekāntavāda – the theory of relative pluralism or manifoldness;

- Syādvāda – the theory of conditioned predication and;

- Nayavāda – The theory of partial standpoints.

These philosophical concepts have made most important contributions to the ancient Indian philosophy, especially in the areas of scepticism and relativity.[21]

Anekāntavāda

.jpg)

One of the most important and fundamental doctrines of Jainism is Anēkāntavāda. It refers to the principles of pluralism and multiplicity of viewpoints, the notion that truth and reality are perceived differently from diverse points of view, and that no single point of view is the complete truth.[22][23]

Jains contrast all attempts to proclaim absolute truth with adhgajanyāyah, which can be illustrated through the parable of the "blind men and an elephant". In this story, each blind man felt a different part of an elephant (trunk, leg, ear, etc.). All the men claimed to understand and explain the true appearance of the elephant, but could only partly succeed, due to their limited perspectives.[24] This principle is more formally stated by observing that objects are infinite in their qualities and modes of existence, so they cannot be completely grasped in all aspects and manifestations by finite human perception. According to the Jains, only the Kevalis—omniscient beings—can comprehend objects in all aspects and manifestations; others are only capable of partial knowledge.[25] According to the doctrine, no single, specific, human view can claim to represent absolute truth.[22]

Anekāntavāda encourages its adherents to consider the views and beliefs of their rivals and opposing parties. Proponents of anekāntavāda apply this principle to religion and philosophy, reminding themselves that any religion or philosophy—even Jainism—which clings too dogmatically to its own tenets, is committing an error based on its limited point of view.[26] The principle of anekāntavāda also influenced Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to adopt principles of religious tolerance, ahiṃsā and satyagraha.[27]

Syādvāda

Syādvāda is the theory of conditioned predication, which provides an expression to anekānta by recommending that the epithet Syād be prefixed to every phrase or expression.[28] Syādvāda is not only an extension of anekānta ontology, but a separate system of logic capable of standing on its own. The Sanskrit etymological root of the term syād is "perhaps" or "maybe", but in the context of syādvāda, it means "in some ways" or "from a perspective". As reality is complex, no single proposition can express the nature of reality fully. Thus the term "syāt" should be prefixed before each proposition giving it a conditional point of view and thus removing any dogmatism in the statement.[23] Since it ensures that each statement is expressed from seven different conditional and relative viewpoints or propositions, syādvāda is known as saptibhaṅgīnāya or the theory of seven conditioned predications. These seven propositions, also known as saptibhaṅgī, are:[29]

- syād-asti—in some ways, it is,

- syād-nāsti—in some ways, it is not,

- syād-asti-nāsti—in some ways, it is, and it is not,

- syād-asti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is, and it is indescribable,

- syād-nāsti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is not, and it is indescribable,

- syād-asti-nāsti-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is, it is not, and it is indescribable,

- syād-avaktavyaḥ—in some ways, it is indescribable.

Each of these seven propositions examines the complex and multifaceted nature of reality from a relative point of view of time, space, substance and mode.[29] To ignore the complexity of reality is to commit the fallacy of dogmatism.[23]

Nayavāda

Nayavāda is the theory of partial standpoints or viewpoints. Nayavāda is a compound of two Sanskrit words—naya ("partial viewpoint") and vāda ("school of thought or debate").[30] It is used to arrive at a certain inference from a point of view. An object has infinite aspects to it, but when we describe an object in practice, we speak of only relevant aspects and ignore irrelevant ones.[30] This does not deny the other attributes, qualities, modes and other aspects; they are just irrelevant from a particular perspective. Authors like Natubhai Shah explain nayavāda with the example of a car;[31] for instance, when we talk of a "blue BMW" we are simply considering the color and make of the car. However, our statement does not imply that the car is devoid of other attributes like engine type, cylinders, speed, price and the like. This particular viewpoint is called a naya or a partial viewpoint. As a type of critical philosophy, nayavāda holds that all philosophical disputes arise out of confusion of standpoints, and the standpoints we adopt are, although we may not realise it, "the outcome of purposes that we may pursue".[32] While operating within the limits of language and seeing the complex nature of reality, Māhavīra used the language of nayas. Naya, being a partial expression of truth, enables us to comprehend reality part by part.[31]

Ethics

The Jain morality and ethics are rooted in its metaphysics and its utility towards the soteriological objective of liberation. Jaina ethics evolved out of the rules for the ascetics which are encapsulated in the mahavratas or the five great vows

- Ahimsa, non-violence

- Satya, truth

- Asteya, non-stealing

- Brahmacharya, celibacy

- Aparigraha, non-possession

These ethics are governed not only through the instrumentality of physical actions, but also through verbal action and thoughts. Thus, ahimsa has to be observed through mind, speech, and body. The other rules of the ascetics and laity are derived from these five major vows.

Jainism does not invoke fear of or reverence for God or conformity to the divine character as a reason for moral behaviour, and observance of the moral code is not necessary simply because it is God's will. Neither is its observance necessary simply because it is altruistic or humanistic, conducive to general welfare of the state or the community. Rather it is an egoistic imperative aimed at self-liberation. While it is true that in Jainism, the moral and religious injunctions were laid down as law by Arihants who have achieved perfection through their supreme moral efforts, their adherence is just not to please a God, but because the life of the Arihants has demonstrated that such commandments were conductive to the Arihant's own welfare, helping him to reach spiritual victory. Just as the Arihants achieved moksha or liberation by observing the moral code, so can anyone, who follows this path.

Atomism

The most elaborate and well-preserved Indian theory of atomism comes from the philosophy of the Jaina school, dating back to at least the 6th century BC. Some of the Jain texts that refer to matter and atoms are Pancastikayasara, Kalpasutra, Tattvarthasutra and Pannavana Suttam. The Jains envisioned the world as consisting wholly of atoms, except for souls. Paramāņus or atoms were the basic building blocks of matter. Their concept of atoms was very similar to classical atomism, differing primarily in the specific properties of atoms. Each atom, according to Jain philosophy, has one kind of taste, one smell, one color, and two kinds of touch, though it is unclear what was meant by "kind of touch". Atoms can exist in one of two states: subtle, in which case they can fit in infinitesimally small spaces, and gross, in which case they have extension and occupy a finite space. Certain characteristics of Paramāņu correspond with that of sub-atomic particles. For example Paramāņu is characterized by continuous motion either in a straight line or in case of attractions from other Paramāņus, it follows a curved path. This corresponds with the description of orbit of electrons across the Nucleus. Ultimate particles are also described as particles with positive (Snigdha i.e. smooth charge) and negative (Rūksa – rough) charges that provide them the binding force. Although atoms are made of the same basic substance, they can combine based on their eternal properties to produce any of six "aggregates", which seem to correspond with the Greek concept of "elements": earth, water, shadow, sense objects, karmic matter, and unfit matter. To the Jains, karma was real, but was a naturalistic, mechanistic phenomenon caused by buildups of subtle karmic matter within the soul. They also had detailed theories of how atoms could combine, react, vibrate, move, and perform other actions, which were thoroughly deterministic.

Infinity

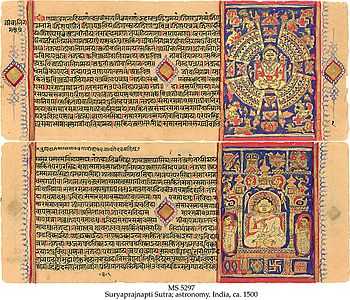

The Jain mathematical text Surya Prajnapti (c. 400 BC) classifies numbers into three sets: enumerable, innumerable, and infinite. Each of these was further subdivided into three orders:

- Enumerable: lowest, intermediate and highest

- Innumerable: nearly innumerable, truly innumerable and innumerably innumerable

- Infinite: nearly infinite, truly infinite, infinitely infinite

The Jains were the first to discard the idea that all infinites were the same or equal. They recognized different types of infinities: infinite in length (one dimension), infinite in area (two dimensions), infinite in volume (three dimensions), and infinite perpetually (infinite number of dimensions).

According to Singh (1987), Joseph (2000) and Agrawal (2000), the highest enumerable number N of the Jains corresponds to the modern concept of aleph-null  (the cardinal number of the infinite set of integers 1, 2, ...), the smallest cardinal transfinite number. The Jains also defined a whole system of infinite cardinal numbers, of which the highest enumerable number N is the smallest.

(the cardinal number of the infinite set of integers 1, 2, ...), the smallest cardinal transfinite number. The Jains also defined a whole system of infinite cardinal numbers, of which the highest enumerable number N is the smallest.

In the Jaina work on the theory of sets, two basic types of infinite numbers are distinguished. On both physical and ontological grounds, a distinction was made between asaṃkhyāta ("countless, innumerable") and ananta ("endless, unlimited"), between rigidly bounded and loosely bounded infinities.

Contributions to Indian philosophy

Jainism had a major influence in developing a system of philosophy and ethics that had a major impact on Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The scholarly research and evidences have shown that philosophical concepts that are typically Indian – Karma, Ahimsa, Moksa, reincarnation and like – either have their origins in the shramana traditions or were propagated and developed by Jain teachers. The sramanic ideal of mendicancy and renunciation, that the worldly life was full of suffering and that emancipation required giving up of desires and withdrawal into a lonely and contemplative life, was in stark contrast with the brahmanical ideal of an active and ritually punctuated life based on sacrifices, household duties and chants to deities. Sramanas developed and laid emphasis on Ahimsa, Karma, moksa and renunciation.[33][34]

Schools and traditions

Jain philosophy arose from the shramana traditions. In its 2500 years post-Mahavira history, it remained fundamentally the same as preached by Mahavira, who preached essentially the same religion as the previous Tirthankara. However, he modified the four vows of Parshva by adding a fifth vow, celibacy. Jain texts like the Uttaradhyana Sutra speak of parallel existence the order of Parsva which was ultimately merged into Mahaviras order. Harry Oldmeadow notes that the Jain philosophy remained fairly standard throughout history and the later elaborations only sought to further elucidate preexisting doctrine and avoided changing the ontological status of the components.[35] The schisms into Śvetāmbara and Digambara traditions arose mainly on account of differences in question of practice of nudity amongst monks and liberation of women. Apart from these minor differences in practices, there are no major philosophical differences between the different sects of Jainism. The Tattvārthasūtra, which encapsulates major philosophical doctrines, is accepted by all traditions of Jainism. This coherence in philosophical doctrine and consistency across different schools has led scholars like Jaini to remark that in the course of history of Jainism no heretical movements like Mahayana, tantric or bhakti movement developed outside mainstream Jainism.[36] Thus, there are traditions within Jainism, but basically the same philosophy that is at the core of Jainism.

Earlier traditions

As per the tradition, Jain Sangh was divided into two major sects:

- Śvetāmbaras believe that women can attain liberation and that nudity is optional. Śvetāmbara scriptures support both acelakatva, nudity in monks and sacelakatva, the wearing of white clothes by ascetics. They also hold that the Jain canon was not lost.

- Digambaras hold that nudity is necessary for liberation and only men can attain the final stage of non-attachment to the body by remaining nude. They also hold that the canonical literature was eventually lost.

The now defunct Yapaniya sect followed the Digambara practice of nudity and eating from the hands while standing up along with Śvetāmbara beliefs and texts. They notably also permitted their ascetics to be "half-clothed" (ardhambara) in public areas only. The Yapaniya sect was absorbed into the Digambara community during the medieval period.

Medieval traditions

The period of 16th to 18th century was a period of reforms in Jainism. The later schools arose against certain practices and belief that were perceived as corrupting and not sanctioned by scriptures. The following schools arose during this period :

- Sthanakvasi – The Sthanakvasis, arising from the Śvetāmbara tradition, rejected idol worship as unsanctioned by scriptures.

- Terapanthi (Digambara) – The Digambara Terapantha movement arose in protest against the institution of Bhattarakas (Jain priestly class), usage of flowers and offerings in Jain temples, and worship of minor gods.

- Terapanthi (Śvetāmbara) – The Terapanthi, also a non-iconic sect, arose from Sthanakvasis on account of differences in religious practices and beliefs.

Recent developments

Recent events lead to dissatisfaction with the monastic tradition and its related emphasis on austerities saw the arising of two new sects within Jainism in the 20th century. These were essentially led by the laity rather than ascetics and soon became a major force to be reckoned with. The non-sectarian cult of Shrimad Rajchandra, who was one of the major influences on Mahatma Gandhi, is now one of the most popular movements. Another cult founded by Kanjisvami, laying stress on determinism and "knowledge of self", has gained a large following as well.

Jain philosophers

Jains hold the Jain doctrine to be eternal and based on universal principles. In the current time cycle, they trace the origins of its philosophy to Rsabha, the first Tīrthankara. However, the tradition holds that the ancient Jain texts and Purvas which documented the Jain doctrine were lost and hence, historically, the Jain philosophy can be traced from Mahāvīras teachings. Post Mahāvīra many intellectual giants amongst the Jain ascetics contributed and gave a concrete form to the Jain philosophy within the parameters set by Mahavira. Following is the partial list of Jain philosophers and their contributions:

- Kundakunda (1st—2nd century CE) – exponent of Jain mysticism and Jain nayas dealing with the nature of the soul and its contamination by matter, author of Pañcāstikāyasāra "Essence of the Five Existents", the Pravacanasāra "Essence of the Scripture", the Samayasāra "Essence of the Doctrine", Niyamasāra "Essence of Discipline", Atthapāhuda "Eight Gifts", Dasabhatti "Ten Worships" and Bārasa Anuvekkhā "Twelve Contemplations".

- Samantabhadra (2nd century CE) – first Jain writer to write on nyāya, (Apta-Mimāmsā), which has had the largest number of commentaries written on it by later Jain logicians. He also composed the Ratnakaranda Srāvakācāra and the Svayambhu Stotra.

- Umāsvāti or Umasvami (2nd century CE) – author of first Jain work in Sanskrit, Tattvārthasūtra, expounding philosophy in a most systematised form acceptable to all sects of Jainism.

- Siddhasena Divākara (5th century) – Jain logician and author of important works in Sanskrit and Prakrit, such as, Nyāyāvatāra (on Logic) and Sanmatisūtra (dealing with the seven Jaina standpoints, knowledge and the objects of knowledge).[37]

- Akalanka (5th century) – key Jain logician, whose works such as Laghiyastraya, Pramānasangraha, Nyāyaviniscaya-vivarana, Siddhiviniscaya-vivarana, Astasati, Tattvārtharājavārtika, et al. are seen as landmarks in Indian logic. The impact of Akalanka may be surmised by the fact that Jain Nyāya is also known as Akalanka Nyāya.

- Pujyapada (6th century) – Jain philosopher, grammarian, Sanskritist. Composed Samadhitantra, Ishtopadesha and the Sarvarthasiddhi, a definitive commentary on the Tattvārthasūtra and Jainendra Vyakarana, the first work on Sanskrit grammar by a Jain monk.

- Manikyanandi (6th century) – Jain logician, composed the Parikshamaukham, a masterpiece in the karika style of the Classical Nyaya school.

- Jinabhadra (6th–7th century) – author of Avasyaksutra (Jain tenets) Visesanavati and Visesavasyakabhasya (Commentary on Jain essentials) He is said to have followed Siddhasena and compiled discussion and refutation on various views on Jaina doctrine.

- Mallavadin (8th century) – author of Nayacakra and Dvadasaranayacakra (Encyclopedia of Philosophy) which discusses the schools of Indian Philosophy.[37] Mallavadin was known as a vadin i.e. a logician and he is said to have defeated Buddhist monks on the issues of philosophy.

- Haribhadra (8th century) – Jain thinker, author, philosopher, satirist and great proponent of anekāntavāda and classical yoga, as a soteriological system of meditation in the Jain context. His works include Ṣaḍdarśanasamuccaya, Yogabindu and Dhurtakhyana. he pioneered the Dvatrimshatika genre of writing in Jainism, where various religious subjects were covered in 32 succinct Sanskrit verses.[37]

- Prabhacandra (8th–9th century) – Jain philosopher, composed a 106-Sutra Tattvarthasutra and exhaustive commentaries on two key works on Jain Nyaya, Prameyakamalamartanda, based on Manikyanandi's Parikshamukham and Nyayakumudacandra on Akalanka's Laghiyastraya.

- Abhayadeva (1057 to 1135) – author of Vadamahrnava (Ocean of Discussions) which is a 2,500 verse tika (Commentary) of Sanmartika and a great treatise on logic.[37]

- Acharya Hemachandra (1089–1172) – Jain thinker, author, historian, grammarian and logician. His works include Yogaśāstra and Trishashthishalakapurushacaritra and the Siddhahemavyakarana.[37] He also authored an incomplete work on Jain Nyāya, titled Pramāna-Mimāmsā.

- Vadideva (11th century) – He was a senior contemporary of Hemacandra and is said to have authored Paramananayatattavalokalankara and its voluminous commentary syadvadaratnakara that establishes the supremacy of doctrine of Syādvāda.

- Vidyanandi (11th century) – Jain philosopher, composed the brilliant commentary on Acarya Umasvami's Tattvarthasutra, known as Tattvarthashlokavartika.

- Yaśovijaya (1624–1688) – Jain logician and one of the last intellectual giants to contribute to Jain philosophy. He specialised in Navya-Nyāya and wrote Vrttis (commentaries) on most of the earlier Jain Nyāya works by Samantabhadra, Akalanka, Manikyanandi, Vidyānandi, Prabhācandra and others in the then-prevalent Navya-Nyāya style. Yaśovijaya has to his credit a prolific literary output – more than 100 books in Sanskrit, Prakrit, Gujarati and Rajasthani. He is also famous for Jnanasara (essence of knowledge) and Adhayatmasara (essence of spirituality).

In recent times, Aacharya Mahapragya, Pt. Sukhlal and Dr. Mahendrakumar Nyayacarya have made important contributions to Jain Philosophy.

Notes

- ↑ Shah 1998, p. 47

- ↑ Oldmeadow 2007, p. 149

- ↑ Shah 1998, p. 44

- ↑ Sanghvi 2008, p. 26

- ↑ James 1969, p. 45

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 100

- ↑ Kritivijay 1957, p. 21

- ↑ Jaini 2000, p. 122

- ↑ Allday 2001, p. 268

- ↑ Shah 1998, pp. 35–38

- ↑ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 271–272

- ↑ Glasenapp 1999, pp. 272

- ↑ Dundas 2002, p. 40

- ↑ Shah 1998, p. 25

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Shah 1998, pp. 29–31

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Schubring 1995, pp. 204–246

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Shah 1998, pp. 31–33

- ↑ CIL. "Indian Cosmology Reflections in Religion and Metaphysics". Ignca.nic.in. Retrieved 2012-02-25.

- ↑ Shah 1998, pp. 27–28

- ↑ Prasad 2006, pp. 60–61

- ↑ McEvilley 2002, p. 335

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Sethia 2004, pp. 123–136

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Sethia 2004, pp. 400–407

- ↑ Hughes 2005, pp. 590–591

- ↑ Jaini 1998, p. 91

- ↑ Huntington, Ronald. "Jainism and Ethics". Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-11.

- ↑ Hay 1970, pp. 14–23

- ↑ Chatterjea 2001, pp. 77–87

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Grimes 1996, p. 312

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Grimes 1996, pp. 202–203

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Shah 1998, p. 80

- ↑ McEvilley 2002, pp. 335–337

- ↑ Pande 1994, pp. 134–136

- ↑ Worthington 1982, pp. 27–30

- ↑ Oldmeadow 2007, p. 148

- ↑ Jaini 2000, pp. 31–35

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Jaini 1998, p. 85

References

- Grimes, John (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. New York: Suny Press. ISBN 0-7914-3068-5.

- Chatterjea, Tara (2001). Knowledge and Freedom in Indian Philosophy. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 0-7391-0692-9.

- Hay, Stephen N. (1970). "Jain Influences on Gandhi's Early Thought". In Sibnarayan Ray. Gandhi India and the World. Bombay: Nachiketa Publishers.

- Hughes, Marilynn (2005). The voice of Prophets. Volume 2 of 12. Morrisville, North Carolina: Lulu.com. ISBN 1-4116-5121-9.

- Sethia, Tara (2004). Ahiṃsā, Anekānta and Jainism. Motilal Banarsidass.

- Schubring, Walther (1995). "Cosmography". In Wolfgang Beurlen. The Doctrine of the Jainas. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0933-5.

- Glasenapp, Helmuth Von (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1376-6.

- Glasenapp, Helmuth Von (2003). Hiralal Rasikdas Kapadia, ed. The Doctrine of Karman in Jain Philosophy. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 9780895819710.

- Sanghvi, Jayatilal S. (2008). A Treatise on Jainism. Forgotten Books. ISBN 9781605067285.

- Dundas, Paul (2002). The Jains. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26606-8.

- Jaini, Padmanabh (1998). The Jaina Path of Purification. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1578-5.

- Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1691-9.

- James, Edwin Oliver (1969). Creation and Cosmology: A Historical and Comparative Inquiry. Netherland: Brill. ISBN 90-04-01617-1.

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought: Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. New York: Allworth Communications. ISBN 1-58115-203-5.

- Oldmeadow, Harry (2007). Light from the East: Eastern Wisdom for the Modern West. Indiana: World Wisdom. ISBN 1-933316-22-5.

- Pande, Govindchandra (1994). Life and Thought of Sankaracarya. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1104-6.

- Shah, Natubhai (1998). Jainism: The World of Conquerors. Volume I and II. Sussex: Sussex Academy Press. ISBN 1-898723-30-3.

- Worthington, Vivian (1982). A History of Yoga. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7100-9258-X.

- Zydenbos, Robert J. (2006). Jainism Today and Its Future. München: Manya Verlag.

Further reading

- 'Jaina Epistemology' by S. Srikanta Sastri, Published in 'The Jaina Vidya' October 1941.

- Brodd, Jeffery; Gregory Sobolewski (2003). World Religions: A Voyage of Discovery. Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 0-88489-725-7.

- Carrithers, Michael (June 1989). "Naked Ascetics in Southern Digambar Jainism". Man, New Series (UK: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland) 24 (2): 219–235. JSTOR 2803303.

- Dr. Bhattacharya, H. S. (1976). Jain Moral Doctrine. Mumbai: Jain Sahitya Vikas Mandal.

- Jacobi, Hermann; Ed. F. Max Müller (1895). Uttaradhyayana Sutra, Jain Sutras Part II, Sacred Books of the East, Vol. 45. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Koller, John M. (July 2000). "Syadvada as the Epistemological Key to the Jaina Middle Way Metaphysics of Anekantavada". Philosophy East and West (Honululu) 50 (3): 400–7. doi:10.1353/pew.2000.0009. ISSN 0031-8221. JSTOR 1400182.

- Kuhn, Hermann (2001). Karma, The Mechanism : Create Your Own Fate. Wunstorf, Germany: Crosswind Publishing. ISBN 3-9806211-4-6.

- Gopani, A. S.; Surendra Bothara ed. (1989). Yogaśāstra (Sanskrit) of Ācārya Hemacandra. Jaipur: Prakrit Bharti Academy.

- Mohanty, Jitendranath (2000). Classical Indian Philosophy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8933-6.

- Nayanar, A. Chakravarti (2005). Pañcāstikāyasāra of Ācārya Kundakunda. New Delhi: Today & Tomorrows Printer and Publisher. ISBN 81-7019-436-9.

- Nayanar, A. Chakravarti (2005). Samayasāra of Ācārya Kundakunda. Kunda Kunda Acharya ; the original text in Prakrit, with its Sanskrit renderings, and a translation, exhaustive commentaries, and an introduction by J.L. Jaini ; assisted by Brahmachari Sital Prasada Ji. New Delhi: Today & Tomorrows Printer and Publisher. ISBN 9788170193647.

- Sangave, Dr. Vilas A. (2001). Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. ISBN 81-7154-839-3.

- Soni, Jayandra; E. Craig (Ed.) (1998). "Jain Philosophy". Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (London: Routledge). Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- Umāsvāti (1994). (tr.) Nathmal Tatia, ed. Tattvārtha Sūtra : That which Is (in Sanskrit – English). Lanham, MD: Rowman Altamira. ISBN 0-7619-8993-5.

- Vallely, Anne (2002). Guardians of the Transcendent: An Ethnography of a Jain Ascetic Community. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8415-X.

- Warren, Herbert (2001). Jainism. Delhi: Crest Publishing House. ISBN 81-242-0037-8.

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1969). (ed.) Joseph Campbell, ed. Philosophies of India. New York: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01758-1.

- Zydenbos, Robert J. (2006). Jainism Today and Its Future. München: Manya Verlag.

External links

- Jain philosophy entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||