Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió

| Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Born |

Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió 1889 Torralba de Calatrava, Spain |

| Died |

1934 Guadarrama, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Ethnicity | Spanish |

| Occupation | lawyer, landowner |

| Known for | Politician |

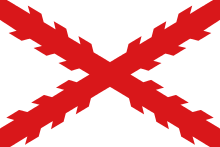

Political party | Conservative Party, Comunión Tradicionalista |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió (Torralba de Calatrava, 1889 - Guadarrama, 1934) was a Spanish Conservative and Carlist/Traditionalist politician.

Family and Youth

Jaime Chicharro Sánchez-Guió was born to a wealthy family of Castillan landowners, already forming part of the local oligarchy. Son of José Chicharro Martín del Moral and Soledad Sánchez-Guio Ruiz-Hidalgo, he had two sisters, all raised in a fervently conservative atmosphere with a strong Carlist leaning. Attended the Jesuit Colegio Nuestra Señora del Recuerdo in the Madrid district of Chamartín de la Rosa, later to graduate in law from the Jesuit Deusto College in Bilbao and in Philosophy and Letters from the Universidad Central (later Universidad Complutense) in Madrid.

Married to Dolores Lamamié de Clairac Romero y Bermúdez de Castro, sister of the Salamancan landowner and later a well-known Carlist politician, José María Lamamié de Clairac y de la Colina; they moved to the spouse’s La Salmantina estate, now located in the municipality of Les Alqueries (Castellón province). The couple had 13 children. The oldest daughter was repeatedly raped and eventually killed by the Republican militia in Madrid in 1936. Three sons volunteered to the Carlist Requetés; one of them died in 1939 due to tortures suffered in the Republican jail, the others became Francoist generals. The next three males volunteered to División Azul (two died in combat, the surviving one grew to a general as well). The youngest son became known as a wrestling champion in the 1950s.

Early career

Though sharing the ultraconservative outlook of his ancestors, initially Chicharro remained somewhat on the margins of the Traditionalist movement. His brother-in-law and friend José Lamamié de Clairac, who was only 2 years Chicharro's senior, exposed him to the schismatic Integrist political vision. When studying in Madrid he met and adhered to Juan Vázquez de Mella, another dissenting Carlist. Possibly as a result, upon his return to Castellón in 1914, Chicharro did not join the Traditionalists, especially that they were locally divided between the mainstream purs and the dissident paquistes, followers of Francisco Giner Lila. Instead, he remained active within a broadly conservative, Catholic and monarchist realm, i.a. setting up, with rather modest results, the local Catholic trade unions. It was only in 1916 that he entered the newly organised local Carlist Junta Provincial and became its first vicepresident (and head of the local Villarreal circle). He left the mainstream Traditionalism only two years later, after the mellists broke away formally to build their own political group in 1918.

Restauración

In the 1916 elections to the Cortes Chicharro decided to stand as a conservative candidate in the Levantine Nules district, forming part of the contenders loyal to the Murcian party leader, Juan de la Cierva y Peñafiel. Having lost, he tried his luck again in Nules in 1918, this time representing the purs faction of the Carlists and supported by a partially controlled newspaper, La Gaceta de Levante. Facing a united opposition of the mauristas and paquistes Chicharro lost again, but in 1919, standing as a catholic-monarchist ciervista, he was finally successful with 4808 votes (out of 8823 votes cast). During the successive elections of 1920 the local mainstream Carlists supported a governmental candidate against Chicharro. Despite this call, he was re-elected and served in the parliament until 1923, forming part of the local Murcian-Levantine cacique network of the Conservative Party.

In the parliament, at that time dominated by the Conservatives of Eduardo Dato, Chicharro remained a rather restless and turbulent deputy, occasionally sliding to opposition. Apart from the customary anti-liberal diatribes, he was particularly vocal on financial issues, entering into dramatic taxation and budgetary disputes with the Minister of Economy. His most lasting achievement is a Royal Order, which marked significant state resources for development of the local Burriana harbor. The design, apart from massive upgrade of the facilities, envisaged also major investments which connected the port with the national railroad network. The work was carried out until the early 1930s and transformed what used to be chiefly a simple fishing bay into a small but modern commercial transport hub. Key beneficiaries of the project were the local Levantine landowners, who gained a gateway for the export of their orange production. In recognition of his merits, the city of Burriana named Chicharro its hijo adoptivo; upon his return from Madrid he was greeted with arches of triumph and venerating celebrations.

During the 1923 electoral campaign Chicharro ruined his chances when engaged in a scandal. During one of the meetings in the very same city of Burriana, he was challenged by a local workers’ leader. Chicharro resolved to a stick and engaged in a brawl, resulting in his victim treated in a hospital for head wounds and an administrative action taken against the assailant.

Primo de Rivera dictatorship

During the early years of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship the Chicharro family left Levante and moved to Madrid, where Jaime started to practice as a lawyer. In 1927 he entered the Ayunatmiento of Madrid as one of the 64 new city councillors; he was responsible for the Chamberí district and specialized in the education and schooling issues, having been a member of Junta municipal de Primera enseñanza. He resumed his contacts with Vázquez de Mella and just weeks after his death, in March 1928, arranged for a commemorative plaque to be mounted on the Escuela Normal de Maestros wall. During the last years of the monarchy he seemed politically disoriented. He continued his activity in conservative Catholic groupings like Acción social, giving lectures and contributing as organizer and manager; as a close relative and friend of José Lamamié he maintained links with his Acción Castellana, set up in 1930, and was drawn closer to another of his organizations, Federación Católico-Agraria Salmantina; he remained in the circle of Francesc Cambó, leader of the Catalan conservative Lliga Regionalista; last but not least, he retained his Carlist contacts within the orphaned mellist community, now headed by the new leader, Victor Pradera.

The Republic

During the local elections of April 1931 Chicharro was overwhelmed by the republican tide and as a conservative candidate failed to get voted into the Madrid ayuntamiento. After the fall of the monarchy and proclamation of the Republic he decided to take part in the June 1931 elections to the Cortes from Castellón. He was supported by Diario de Castellón, the daily he owned fully and set up back in 1924 (officially the voice of Federación Castellonense de Sindicatos Agrícolas, to be issued until 1936; the newspaper retained an ultraconservative line, usually classified as a rightist, not a Carlist title). He assumed the accidentalist position as to the monarchical question, focusing on his conservative outlook and appearing as “right-republican” (la derecha republicana). The result was rather poor, since he arrived 11th with some 11 thousand votes (out of 96,000).

Following the death of the Carlist claimant Don Jaime in 1931, the three streams of Carlism, the jaimistas, the integristas and the mellistas, were getting nearer, to be united the following year in a new organization, Comunión Tradicionalista. Though he did not count among the national leaders, Chicharro from the outset became very active touring the country, attending meetings, haranguing and publishing in the newspapers. In January 1932 he already gave lecture about collaboration and Carlism; in February he defended the expulsed Jesuits calling to set up a new “order of silence”, in March he labelled the proposed universal suffrage as unjust and lambasted the Republican government for overspending and highly inflated budget. The same month he triggered riots in Soria by proclaiming to a public meeting that he had no intention of surrendering an iota of his wealth without a fight. In April the authorities had to intervene when his meeting was interrupted by a belligerent worker. The same month he got his car stolen from the Madrid street. The same April the Carlist assembly with his presence planned was suspended by the authorities for fear of unrest.

Around that time Chicharro got engaged in conspiracy of José Sanjurjo. Following the disastrously failed coup he was identified as one of the culprits and became subject of the expropriation, designed to boost the floundering Agrarian Reform. Later that year two of his sons were detained and without trial ordered to an exile in the Spanish Sahara outpost of Villa Cisneros, which would soon turn into the Carlist hotbed. Later in 1933 he defended some of the conspirators in court.

The last months

In early 1933 Chicharro, together with his brother-in-law Lamamié, was particularly active mixing with the Alfonsist monarchists, building an alliance known as TYRE (Tradicionalistas y Renovación Española) and entering the local Castellon Liaison Committee of the group. This gained him hostility among the new breed of radical Carlist activists like Jaime del Burgo, who despised fraternization with caciques and debris of the Alfonsine monarchy. Moreover, for the Carlist youth the landowners like Lamamié and Chicharro became marked men as priviledged section of politically dominant potentates, who are obstructing the Agrarian Reform by the feudal egoism of the odious grandees of grain. Indeed, within the Carlist community Chicharro formed the most socially conservative faction, which however did not render him averse to new radical movements. Talking on Mussolini and Hitler, he declared that traditionalism, though not one and the same thing, is very sympathetic towards them, as they are waging war against Judaism, freemasonry and Marxism, building an organized corporative state. What is inacceptable to us is the state's overwhelming sovereignty and dominance. For us the family comes first, followed by municipality, region and state, being the last element in this chain.

Riding the wave of soaring rightist sympathies, in 1933 Chicharro was elected to the Madrid ayuntamiento from the Chamberi district. However, running on the Carlist ticket to the Cortes from Castellón he narrowly lost, though initially he was reported by the press as victorious and his fellow Traditionalist Juan Granell Pascual was indeed elected. At that time he was already seriously ill. Having been generally of rather poor health, as a chain-smoker Chicharro developed grave respiratory problems. He was placed in the tuberculosis-treatment Real Sanatorio de Guadarrama, where he died early 1934.

See also

References

- Julio Aróstegui, Jordi Canal, Eduardo Calleja, El carlismo y las guerras carlistas, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788499700557

- Martin Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis in Spain 1931-1939, Cambridge 1975, ISBN 9780521207294

- Rosa Monlleó Peris [ed.], Castello Al Segle XX, Castellon 2006, ISBN 9788480215640

External links

- Historical Index of Deputies

- Chicharro's offspring discussed at a Francoist forum

- a passage at the Castellon cemetery

- homage to Chicharro by Torralba de Calatrava

- Castellon politics of early 20th century

- local Castellon elections early 20th century

- Chicharro family at geneanet

- history of the Burriana harbor