Jack White (trade unionist)

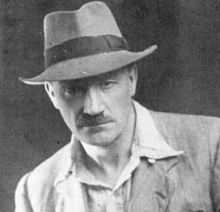

| James Robert "Jack" White | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1879 Broughshane, County Antrim, Ireland |

| Died |

1946 Belfast, Northern Ireland |

| Allegiance |

British Army Irish Republican Brotherhood Irish Citizens Army Irish Volunteers Irish Republican Army Red Cross Republican Congress |

| Years of service | 1897 - 1937 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles/wars |

Boer War Dublin Lockout Easter Rising Irish War of Independence Spanish Civil War |

| Awards |

|

Captain James Robert "Jack" White DSO (1879–1946) was one of the co-founders of the Irish Citizen Army.

Early life

Jack White was born in 1879, at Whitehall, in Broughshane, County Antrim, Ireland. An only son, he initially followed in the footsteps of his father, Field Marshal Sir George Stuart White VC, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE, GCVO, being educated at Winchester College, and later at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. At the age of eighteen, White saw service with the 1st Gordon Highlanders in the Boer War in South Africa. He was decorated with the Distinguished Service Order, The London Gazette of 2 July 1901 in its DSO citation reporting

James Robert White, Lieutenant, The Gordon Highlanders. For having, when taken prisoner, owing to mistaking advancing Boers for British troops, and stripped, escaped from custody and run six miles, warning Colonel de Lisle, and advancing with him to the relief of Major Sladen's force.[1]

White started to develop a dislike for the British ruling classes while in South Africa. It is said that at the battle of Doornkop he was one of the first to go over the top. Looking back, he saw one 17-year-old youth shivering with fright in the trench. An officer cried "shoot him". White is said to have aimed his pistol at the officer and replied, "Do so, and I'll shoot you".[2]

Between 1901 and 1905, he served as aide-de-camp to his father, who was then Governor of Gibraltar, and it was here that he met Mercedes 'Dollie' Mosley, the daughter of a Gibraltar business family and a Roman Catholic. Despite family objections on both sides (the Whites were Anglican), the couple married. White continued his military service in India and Scotland.

Departure from the British Army and return to Ireland

White resigned his commission in 1907, citing disaffection with the army and its role. During the next few years White travelled to Bohemia (then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire), lived in a Tolstoyan commune in England and then travelled and worked in Canada.

Arriving back in Ireland, he found Sir Edward Carson's campaign against Home Rule was beginning. This was the time when the Ulster Volunteers were created to threaten war against the British government if Ireland were granted any measure of self-rule.

Jack organised one of the first Protestant pro-Home Rule meetings, in Ballymoney, to rally Protestant opinion against the Unionist Party and against what he described as its "bigotry and stagnation", that associated Ulster Protestants with conservatism. Another speaker at that meeting, coming from a similar social background, was Sir Roger Casement.

As a result of the Ballymoney meeting White was invited to Dublin. Here he met James Connolly and was converted to socialism. Very impressed by the great struggle to win trade union recognition and resist the attacks of William Martin Murphy and his confederates, he offered his services to the ITGWU at Liberty Hall. He spoke on union platforms with people such as Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, Bill Haywood of the Industrial Workers of the World, and Connolly.

The Irish Citizens Army

In 1913 he proposed the creation of a workers militia to protect picket lines from assaults by the Dublin Metropolitan Police and gangs in pay of the employers. The notion of a Citizen Army, drilled by him, was enthusiastically accepted. Its appearance, as White recollected, "put manners on the police".

He later put his services at the disposal of the Irish Volunteers, believing that a stand had to be taken against British rule by a large body of armed people. He went to Derry, where there was a brigade of Volunteers who were largely ex-British Army like himself. But he was shaken by the sectarian attitudes he found. When he tried to reason with them and make the case for workers' unity they dismissed him as merely sticking up for his own, i.e. Protestants.

When Connolly was sentenced to death after the 1916 Rising, White rushed to South Wales and tried to bring the miners out on strike to save his life. For his attempts, he was given three months imprisonment. Transferred from Swansea to Pentonville the day before Roger Casement’s death, White was within earshot of the next morning’s hanging.

The Republican Congress

When he returned during the Irish War of Independence he was left in the political wilderness. He moved towards the newly founded Communist Party of Ireland, however he had his doubts about them and never joined. He returned to England and became involved with Sylvia Pankhurst's anti-parliamentary communist group, the Workers Socialist Federation.

In 1934 a special convention was held in Athlone, attended by 200 former Irish Republican Army (IRA) volunteers and a number of prominent socialists, communists and trade unionists. It resolved that a Republican Congress be formed. This was a movement, based on workers and small farmers, that was well to the left of the IRA. White joined immediately and organised a Dublin branch composed solely of ex-British servicemen.

The Congress later split between those who stood for class independence, those who fought only for a workers republic, and those - led by the communists - who firstly wanted an alliance with Fianna Fáil to reunite the country. After the bulk of the first group walked out (many of them later joining the Labour Party), White remained in the depleted organisation.

The Spanish Civil War

In the late 1930s, he went to Spain during the Spanish Civil War as a medic with the Red Cross. Here he made contact with the anarchist CNT-FAI. Impressed by the social revolution that had unfolded in Spain, White was further attracted to the anarchist cause due to his own developing anti-Stalinism. Never at home with the Communist left in Ireland, he wrote the short pamphlet The Meaning of Anarchy that explained the background to the May '37 street battle and struggle in Barcelona between the anarchists and Stalinists. Returning to London from Spain, he worked with Spain and the World, a pro-libertarian propaganda group active in Britain in support of the Spanish anarchists. While in London, he met his second wife, Noreen Shanahan, the daughter of an Irish government official. They had three children, Anthony, Alan and Derrick. He had had one child, a daughter Ave, from his first marriage with the Gibraltarian Dolly Mosley.

Later years and death

In 1938 they returned to White Hall in Broughshane, White having inherited it from his mother after her death in 1935. His return was undoubtedly prompted by the practicalities of having to provide for his new family. White received a regular income from the rent and sale of the lands attached to the estate, supplemented by occasional income from journalistic efforts. Despite the relative isolation of Broughshane, he remained in regular contact with his political associates, although the outbreak of World War II paralysed any real work.

White made a final and brief reappearance in public life during the 1945 General Election campaign. Proposing himself as a 'republican socialist' candidate for the Antrim constituency, he convened a meeting at the local Orange Hall in Broughshane to outline his view. A witness to the proceeding, recorded that White 'commanded a rich vocabulary of language' directed at a plethora of targets that included Adolf Hitler, Pope Pius XII, Lord Brookborough and Éamon de Valera. However, noted the reporter, White reserved particular contempt for the 'Orange Order and the Unionist Party for the control they exercised over coercion through the Special Powers Act.'

White worked with a Liverpool-Irish anarchist, Matt Kavanagh, on a survey of Irish labour history in relation to anarchism. In 1946 White died from cancer in a Belfast nursing home. After a private ceremony, he was buried in the White family plot in the First Presbyterian Church in Broughshane. It was widely believed that his family, ashamed of Jack's revolutionary politics, destroyed all his papers, including a study of the Cork Harbour Soviet of 1921. However Leo Keohane, White's most recent biographer, believes that this view is unfounded: 'In conversation with the family and from the correspondence I have seen, I would surmise that it is quite probable that the papers are mouldering in some solicitors' redundant files.'[3]

His youngest son Derrick White was a prominent member of the Scottish Nationalist Party and later the Scottish Socialist Party

See also

Notes

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 27329. p. 4401. 2 July 1901.

- ↑ Reg Reynolds. Captain Jack the Governor’s Son, The Gibraltar Magazine online edition. Accessed 6 June 2008

- ↑ Leo Keohane, Captain Jack White: Imperialism, Anarchism and the Irish Citizen Army. Dublin: Merrion Press, 2014, p.2.

References

- Kevin Doyle(July 2001) Captain Jack White (1879-1946) on an archived website of the Workers Solidarity Movement. Accessed 6 June 2008, A biography of Jack White.

- Leo Keohane, Captain Jack White: Imperialism, Anarchism and the Irish Citizen Army. Dublin: Merrion Press, September 2014. Hardback ISBN 9781908928931.

Bibliography

- Misfit: A Revolutionary Life by Jack White Dublin: Livewire Publications, 2005. ISBN 978-1-905225-20-0

Further reading

- J. R. White A rebel in Barcelona: Jack White's first Spanish impressions CNT-AIT Boletin de Informacion. No. 15, 11 November 1936. This article was reproduced from KSL No 14, March 1998. The KSL is the Bulletin of the Kate Sharpley Library, an anarchist library. It is also republished by Ciaran Crossey on the website Ireland and the Spanish Civil War at the Wayback Machine (archived October 28, 2009).