Jack Sheppard (novel)

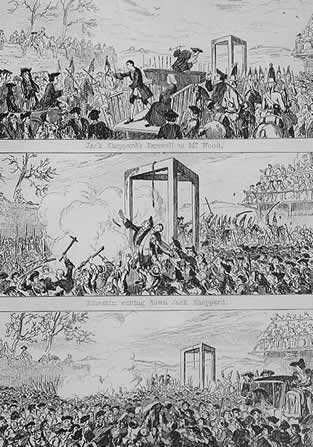

Jack Sheppard is a novel by William Harrison Ainsworth serially published in Bentley's Miscellany from 1839 to 1840, with illustrations by George Cruikshank. It is a historical romance and a Newgate novel based on the real life of the 18th-century criminal Jack Sheppard.

Background

Jack Sheppard was serially published in Bentley's Miscellany from January 1839 until February 1840.[1] The novel was intertwined with the history of Charles Dickens's Oliver Twist which ran at the same time in Bentley's Miscellany. Dickens, previously a friend of Ainsworth's, became distant from Ainsworth as a controversy brewed over the scandalous nature around both Jack Sheppard, Oliver Twist, and other novels describing criminal life. When the relationship between the two dissolved, Dickens retired from the magazine as its editor and made way for Ainsworth to replace him as editor at the end of 1839.[2]

A three volume edition of the work was published by Bentley in October 1839. The novel was adapted to the stage and 8 different theatrical versions were produced in autumn 1839.[1]

Plot summary

The story is divided into three parts, called "epochs". The "Jonathan Wild" epoch comes first. The events of the story begins with the notorious criminal and thief-catcher Jonathan Wild encouraging Jack Sheppard's father to a life of crime. Wild, who once pursues Sheppard's mother, eventually turns Sheppard's father into the authorities and he is soon after executed. Sheppard's mother is left to raise Sheppard, a mere infant at the time, alone.[3]

Paralleling these events is the story of Thames Darrell. On 26 November 1703, the date of the first section, Darrell is removed separated from his immoral uncle, Sir Rowland Trenchard, and is given to Mr. Wood to be raised.[4]

The third epoch takes place in 1724 and spans six months. Sheppard is a thief that spends his time robbing various people. While he and Blueskin rob the Wood's household, Blueskin murders Mrs. Woods. This upsets Sheppard and results in his separation from Wild's group. Sheppard befriends Thames again and spends his time trying to correct Blueskin's wrong.[4]

Characters

- Jack Sheppard

- Jonathan Wild

- Thames Darrell

- Mr. Wood

- Mrs. Wood

- Winifred Wood

- Blueskin – Joseph Blake

- Thomas Sheppard

Themes

Ainsworth's two novels Rookwood and Jack Sheppard were fundamental in popularising the "rogue novel" or "Newgate novel" tradition, a combination of the historical and Gothic novel traditions. The tradition itself stems from a Renaissance literary tradition of emphasising the actions of well-known criminals.[5] Ainsworth's Jack Sheppard is connected to another work within the same tradition that ran alongside it for many months in the Bentley's Miscellany: Dickens' Oliver Twist. The plots are similar, in that both deal with an individual attempting to corrupt a boy. Ainsworth's boy is corrupted, whereas Dickens' is not. Both authors also cast Jews as their villains; they are similar in appearance, though Ainsworth's is less powerful.[6]

According to Frank Chandler, the novel "was intended as a study in the Spanish style".[7] Such influences appear in Jack's physical description and in the words of the characters, including John Gay who states that his life is related to the stories of Guzman d'Alfarache, Lazarillo de Tormes, Estevanillo Gonzalez, Meriton Latroon, and other Spanish rogues. However, there are differences between him and the Spanish characters. His personality is different, especially as he is alternately described as malicious and heroic. He is less sympathetic than his Spanish counterparts until Wild is introduced into the work, whereupon he is seen more favourably. The feud between Wild and Sheppard results in Sheppard giving up his roguish ways. When Sheppard is executed, his character has gained the status of a martyr.[8]

The novel depicts Wild as vicious and cruel, a character who wants to control the London underworld, and, incidentally, to destroy Sheppard. Wild is not focused on the novel's main character, but finds an enemy in anyone whom he feels is no longer useful to him. This is particularly true of Sir Rowland Trenchard, whom Wild murders in a horrific manner. In addition to these actions, Wild is said to have kept a trophy case of items representing cruelty, including the skull of Sheppard's father. In his depictions of Wild's cruel nature and his grotesque murders, Ainsworth went further than his contemporaries would in their novels.[9] As counter to Wild, no matter how depraved Sheppard acts, he is still good. He suffers anguish as a result of his actions, continuing until the very moment of his death at Tyburn. This is not to suggest that his character is free from problems, but that he is depicted only as a thief and not a worse type of criminal.[10]

Morality and moral lessons do play a part within Jack Sheppard. For instance, the second epoch begins with a reflection on the passing of twelve years and how people changed over that length of time.[11] In particular, the narrator asks, "Where are the dreams of ambition in which, twelve years ago, we indulged? Where are the aspirations that fired us—the passions that consumed us then? Has our success in life been commensurate with our own desires—with the anticipations formed of us by others? Or, are we not blighted in heart, as in ambition? Has not the loved one been estranged by doubt, or snatched from us by the cold hand of death? Is not the goal, towards which we pressed, farther off than ever,—the prospect before us cheerless as the blank behind?"[12]

Sources

Jack Sheppard was a well-known criminal in 18th-century London. In terms of the Newgate tradition, those like Daniel Defoe included references to Jack Sheppard in their works. Other figures, including William Hogarth, appear within the work because of their connection to the Newgate tradition. Hogarth is particularly involved because of his "Industry and Idleness" (1747), a series of illustrations that depict the London underworld.[13] Sheppard's rival, Jonathan Wild, also a real criminal, is based on the same character that was used in fiction during the 18th century, including Henry Fielding in his The Life and Death of Jonathan Wild, the Great.[6] Like Hogarth's prints, the novel pairs the descent of the "idle" apprentice into crime with the rise of a typical melodramatic character, Thomas Darrell, a foundling of aristocratic birth who defeats his evil uncle to recover his fortune. Cruikshank's images perfectly complemented Ainsworth's tale—Thackeray wrote that "Mr Cruickshank really created the tale, and that Mr Ainsworth, as it were, only put words to it."[14]

In terms of knowledge of his subject matter and the criminal underworld, Ainsworth did not have any direct knowledge or experience.[15] He admitted in 1878 that he "Never had anything to do with scoundrels in my life. I got my slang in a much easier way. I picked up the Memoirs of one James Hard Vaux a returned transport. The book was full of adventures, and had at the end a kind of slang dictionary. Out of this I got all of my 'patter'."[16]

Response

With its publication, Ainsworth told James Crossley in an 8 October 1839 letter, "The success of Jack is pretty certain, they are bringing him out at half the theatres in London."[17] He was correct and Jack Sheppard was a popular success and sold more books than Ainsworth's previous novels Rookwood and Crichton. It was published in book form in 1839, before the serialised version was completed, and even outsold early editions of Oliver Twist.[18] Ainsworth's novel was adapted into a successful play by John Buckstone in October 1839 at the Adelphi Theatre starring (strangely enough) Mary Anne Keeley; indeed, it seems likely that Cruikshank's illustrations were deliberately created in a form that were informed by, and would be easy to repeat as, tableaux on stage. It has been described as the "exemplary climax" of "the pictorial novel dramatized pictorially".[19] The novel was also adapted as a popular burlesque, Little Jack Sheppard, in 1885.

The story generated a form of cultural mania, embellished by pamphlets, prints, cartoons, plays and souvenirs, not repeated until George du Maurier's Trilby in 1895. While it spawned many imitations and parodies of the novel, it also, according to George Worth, "aroused a very different response: a vigorous outcry concerning its alleged glorification of crime and immorality and the baneful effect which it was bound to have on the young and impressionable."[1] One such outcry came from Mary Russell Mitford that claimed after the novel's publication that "all the Chartists in the land are less dangerous than this nightmare of a book".[20] Public alarm at the possibility that young people would emulate Sheppard's behaviour led the Lord Chamberlain to ban, at least in London, the licensing of any plays with "Jack Sheppard" in the title for forty years. The fear may not have been entirely unfounded: Courvousier, the valet of Lord William Russell, claimed in one of his several confessions that the book had inspired him to murder his master.[21]

In the 1841 Chronicles of Crime, Camden Pelham claimed in regards to influence of Jack Sheppard: "The rage for housebreakers has become immense, and the fortunes of the most notorious and the most successful of thieves have been made the subject of entertainments at no fewer than six of the London theatres."[22] The negative response against Jack Sheppard heightened when the novel was blamed for inspiring the murder of William Russell.[23]

During the outcry, Jack Sheppard was able to become more popular than Dickens's Oliver Twist. This may have prompted Dickens's friend, John Forster, to review the work harshly in the Examiner following its publication.[6] Also, Dickens wanted to separate himself from Ainsworth and Ainsworth's writing, especially that found in the Newgate tradition.[24] In a February 1840 letter to Richard Hengist Horne, he wrote:

I am by some jolter-headed enemies most unjustly and untruly charged with having written a book after Mr. Ainsworth's fashion. Unto these jolter-heads and their intensely concentrated humbug, I shall take an early opportunity of temperately replying. If this opportunity had presented itself and I had made this vindication, I could have no objection to set my hand to what I know to be true concerning the late lamented John Sheppard, but I feel a great repugnance to do so now, lest it should seem an ungenerous and unmanly way of disavowing any sympathy with that school, and a means of shielding myself.[25]

In 1844, Horne wrote that Jack Sheppard "was full of unredeemed crimes, but being told without any offensive language, did its evil work of popularity, and has now gone to its cradle in the cross-roads of literature, and should be henceforth hushed up by all who have—as so many have—a personal regard for its author."[26]

There were many negative responses from other literary figures, including Edgar Allan Poe who wrote in a March 1841 review, "Such libels on humanity, such provocations to crime, such worthless, inane, disgraceful romances as 'Jack Sheppard' and its successors, are a blot on our literature and a curse to our land."[27] Also, William Makepeace Thackeray was a harsh critic of the Newgate novel tradition and expressed his views through parodying aspects of Jack Sheppard in his novel Vanity Fair.[28] Other influences of the novel appear in Bon Gaultier Ballads, especially when they stated:

Turpin, thou should'st be living at this hour: England hath need of thee.Great men have been among us—names that lend A lustre to our calling—better none: Maclaine, Duval, Dick Turpin, Barrington, Blueskin and others who called Sheppard friend.[29]

Charles Mackay, in 1851, re-evaluated the 1841 negative response of the novel and determined that the novel did negatively affect people: "Since the publication of the first edition of this volume, Jack Sheppard's adventures have been revived. A novel upon the real or fabulous history of the burglar has afforded, by its extraordinary popularity, a further exemplification of the allegations in the text."[30] In particular, Mackay declares, "The Inspector's Report on Juvenile Delinquency at Liverpool contains much matter of the same kind; but sufficient has been already quoted to shew the injurious effects of the deification of great thieves by thoughtless novelists."[31] Stephen Carver, in 2003, mentions that "it should be noted that it was the theatrical adaptations consumed by the new urban working class that were considered the social problem [...] What is apparent again and again, as one reconstructs the critical annihilation of Ainsworth, is that the bourgeois establishment neither forgave nor forgot."[32] Furthermore, Carver as argues, "The Newgate controversy invades the textual surface like a virus. After this, the critic has carte blanche to say anything, however vicious, ill-informed or downright libellous."[33]

At the turn of the 20th century, Chandler points out that the "forces of literature rose in revolt" against the novel.[34] Later, Keith Hollingsworth declared Ainsworth's novel as "the high point of the Newgate novel as entertainment".[35] Carver argues, "Had he not abandoned the form that he had effectively originated but rather moderated the moral message to suit the times as Dickens had done, Ainsworth would have likely remained at the cutting edge of Victorian literature for a little while longer."[36]

References

- Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Worth 1972 p. 19

- ↑ Carver 2003 p. 20–21

- ↑ Worth 1972 p. 53

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Worth 1972 p. 54

- ↑ Worth 1972 p. 34

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Worth 1972 p. 37

- ↑ Chandler 1907 p. 366

- ↑ Chandler 1907 pp. 366–368

- ↑ Worth 1972 pp. 77–79

- ↑ Worth 1972 p. 96

- ↑ Worth 1972 pp. 109–110

- ↑ Worth 1972 qtd. p. 110

- ↑ Worth 1972 p. 35

- ↑ Buckley, p.432, from Meisel, pp.247–8.

- ↑ Carver 2003 p. 9

- ↑ Yates 27 March 1878

- ↑ Carver 2003 qtd. p. 7

- ↑ Buckley, p.426.

- ↑ Buckley, p.438, quoting Meisel, p.265.

- ↑ Ellis 1979 Vol. 1 qtd. p. 376

- ↑ Moore, p.229.

- ↑ Pelham 1841 p. 50

- ↑ Hollingsworth 1963 p. 145

- ↑ Carver 2003 p. 22

- ↑ Dickens 1969 p. 20

- ↑ Horne 1844 p. 14

- ↑ Poe 1987 p. 371

- ↑ Worth 1972 pp. 38–39

- ↑ Martin and Aytoun 1841 pp. 215–223

- ↑ Mackay 1995 p. 636

- ↑ Mackay 1995 p. 367

- ↑ Carver 2003 p. 19

- ↑ Carver 2003 p. 30

- ↑ Chandler 1907 p. 358

- ↑ Hollingsworth 1963 p. 132

- ↑ Carver 2003 pp. 19–20

- Bibliography

- Ainsworth, William Harrison. Jack Sheppard. Paris: Galignani and Company, 1840.

- Buckley, Matthew (Spring 2002), Victorian Studies 44 (3): 423–463 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Carver, Stephen (2003), The Life and Works of the Lancashire Novelist William Harrison Ainsworth, 1805–1882, Edwin Mellen Press

- Chandler, Frank. The Literature of Roguery. New York: Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1907.

- Dickens, Charles (1969), The Letters of Charles Dickens 2, Oxford University Press

- Ellis, S. M. William Harrison Ainsworth and His Friends. 2 Vols. London: Garland Publishing, 1979.

- Hollingsworth, Keith (1963), The Newgate Novel, Wayne State University Press

- Horne, Richard Hengist (1844), A New Spirit of the Age, Smith, Elder and Company

- Mackay, Charles (1995), Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, Wordsworth

- Martin, Theodore; Aytoun, William (pseu. Bon Gaultier) (April 1841), Tait's Edinburgh Magazine: 215–223 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Meisel, Martin. (1983) Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton.

- Moore, Lucy (1997), The Thieves' Opera, Viking, ISBN 0-670-87215-6

- Pelham, Camden. Chronicles of Crime, Vol I. London: Tegg et al., 1841.

- Poe, Edgar Allan (1987), The Science Fiction of Edgar Allan Poe, Penguin

- Worth, George (1972), William Harrison Ainsworth, Twayne Publishers

- Yates, Edmund (27 March 1878), The World Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help)

| ||||||||||||||||||