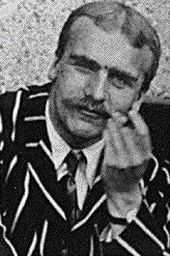

J. B. S. Haldane

| J. B. S. Haldane | |

|---|---|

|

Haldane in 1914. | |

| Born |

5 November 1892 Oxford, England |

| Died |

1 December 1964 (aged 72) Bhubaneswar, India |

| Residence |

United Kingdom

|

| Nationality |

British (until 1961) Indian |

| Fields | |

| Institutions | |

| Alma mater | University of Oxford |

| Academic advisors | Frederick Gowland Hopkins |

| Doctoral students |

Helen Spurway Krishna Dronamraju John Maynard Smith |

| Known for |

Oparin-Haldane hypothesis Malaria theory Population genetics Enzymology Neo-Darwinism |

| Notable awards |

1958 Darwin–Wallace Medal 1952 Darwin Medal |

| Spouse |

1926–45 Charlotte Haldane |

|

Military career | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1914-1920 |

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | First World War |

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, FRS (/ˈhɔːldeɪn/; 5 November 1892 – 1 December 1964)[1] known as "Jack" (but who used 'J. B. S.' in his printed works), was a British naturalised Indian scientist. He was a polymath well known for his works in physiology, genetics and evolutionary biology. He was also a mathematician making innovative contributions to statistics and biometry education in India. In addition, he was an avid politician and science populariser.[2] He was the recipient of National Order of the Legion of Honour (1937), Darwin Medal (1952), Feltrinelli Prize (1961), and Darwin–Wallace Medal (1958). Nobel laureate Peter Medawar, himself recognised as the "wittiest"[3] or "cleverest man", called Haldane "the cleverest man I ever knew".[4] Arthur C. Clarke credited him as "perhaps the most brilliant scientific populariser of his generation".[5][6]

Haldane was born of an aristocratic and secular Scottish family. A precocious boy, he was able to read at age three and was well versed with scientific terminology. His higher education was in mathematics and classics at New College, Oxford. He had no formal degree in science, but was an accomplished biologist. From age eight he worked with his physiologist father John Scott Haldane in their home laboratory. With his father he published his first scientific paper at age 20, while he was only a graduate student. His education was interrupted by the First World War during which he fought in the British Army. When the war ended he resumed as research fellow at Oxford. Between 1922 and 1932 he taught biochemistry at Trinity College, Cambridge. After a year as visiting professor at University of California at Berkeley, in 1933 he became full Professor of Genetics at University College London. He emigrated to India in 1956 to enjoy a lifetime opportunity of not "wearing socks". He worked at the Indian Statistical Institute in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and later in Orissa (now Odisha), where he spent the rest of his life.

His first paper in genetics, written with his sister Naomi, published in 1915 became a landmark as the first demonstration of genetic linkage in mammals. His subsequent works helped to establish a unification of Mendelian genetics and Darwinian evolution by natural selection. Along with Ronald Fisher and Sewall Wright, he laid the groundwork for modern evolutionary synthesis, the concept more popularly known as "neo-Darwinism" (popularised by Richard Dawkins' 1976 work titled The Selfish Gene). Their pioneering combination of mathematics with biology established a branch of science called population genetics. His article on "The origin of life" in 1929, though initially rejected, introduced a new hypothesis "primordial soup theory", now called abiogenesis, the process of formation of cellular life from inorganic molecules on primordial Earth. Independently developed by Russian biochemist Alexander Oparin, the concept came to be called Oparin-Haldane hypothesis, and is the foundation of modern understanding of the chemical origin of life. Haldane was also the first to construct human gene maps for haemophilia and colour blindness on the X chromosome. His "malaria hypothesis" was confirmed to be the genetic basis of resistance to malaria among people with sickle-cell disease.

Haldane was a socialist and a staunch Marxist. He served as chairman of the editorial board of Daily Worker, a Communist newspaper in London, between 1940 and 1949. However, disillusioned by the totalitarian Lysenkoism in Communist Russia, he denounced the party though he continued to admire Vladimir Lenin. From childhood he was known to have strong opposition towards any form of authoritarianism. It was this political dissent that made him leave England and become a "proud" citizen of India. He was particularly critical of Britain's role in the Suez Crisis for which he accused Britain of violating international law.

A renowned atheist, humanist, self-experimenter and prolific author, Haldane is remembered for his several extraordinary visions and witty remarks. He was the first to suggest the central idea of in vitro fertilisation (more popularly "test tube babies"), presented in his lecture/book Daedalus and fictionalized by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World. The concept of hydrogen economy for generating power originated from his Cambridge speech in 1923. Many scientific terms including cis, trans, coupling, repulsion, darwin (as a unit of evolution) were coined by him, as well as the term "clone" to describe the possibility of creating exact copies of humans. His imminent death due to colorectal cancer was lamented by himself in a poem Cancer's a Funny Thing. He willed his body for medical studies, as he wanted to remain useful even in death.[7]

Biography

Family background

Haldane was born in Oxford to John Scott Haldane, a physiologist, and Louisa Kathleen Haldane (née Trotter), and descended from an aristocratic and intellectual Haldane family[8] of the Clan Haldane. (He would later claim that his Y-chromosome could be traced back to Robert the Bruce, a thirteenth-century Scottish king.)[9] His younger sister, Naomi, became a writer. His uncle was Richard Haldane, 1st Viscount Haldane, politician and one time Secretary of State for War; his aunt was the author Elizabeth Haldane. His father was a scientist, a philosopher and a Liberal, and his mother was a Conservative. Haldane took an interest in his father’s work very early in childhood. It was the result of this lifelong study of the natural world and his devotion to empirical evidence that he became an atheist. He felt that atheism was the only rational deduction available in light of all the evidence, saying, "My practice as a scientist is atheistic. That is to say, when I set up an experiment I assume no god, angel or devil is going to interfere with its course... I should therefore be intellectually dishonest if I were not also atheistic in the affairs of the world."[10]

Early life and education

Haldane grew up in 11 Crick Road, North Oxford.[11] A child prodigy, and influenced by his father, he learned to read and was already familiar with some scientific terminologies at age three. At four he injured himself on the forehead, and while a doctor was cleaning his blood, he asked, “Is this oxyhemoglobin or carboxyhemoglobin?” His formal education began in 1897 at Oxford Preparatory School (now Dragon School), where his mathematical ability earned him several prizes including First Scholarship in 1904 to Eton. In 1899 his family moved to "Cherwell", a late Victorian house at the outskirts of Oxford having its private laboratory. It was in this laboratory that Haldane had his only scientific education. At age eight he joined his father in the laboratory where he experienced his first self-experimentation, the method he would later be famous for. They both would in turn served as their own "human guinea pigs" such as in their investigation on the effects of poison gases. In 1905 he joined Eton, where he experienced severe abuse from senior students on his part as being arrogant. The indifference of the authority left him with a lasting hatred for English education system. However, the ordeal did not stop him from becoming Captain of the school. In 1911 he continued at New College, Oxford, and obtained first-class honours in mathematical moderations in 1912. He became engrossed in genetics and presented a paper on gene linkage in vertebrates in the summer of 1912. In June his first technical paper, a 30-page long article on haemoglobin function, was published, as a co-author alongside his father.[12] He did all the mathematics. In the autumn he changed his course to Greats (Classics covering ancient history and philosophy). He completed with first-class honours in 1914. He never earned any degree in science, as the First World War broke out.[9][13]

Career

Haldane joined the British Army during the First World War, being commissioned a temporary second lieutenant in the 3rd Battalion of the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) on 15 August 1914.[14] He was promoted to temporary lieutenant on 18 February 1915 and to temporary captain on 18 October.[15][16] He served in France and Iraq, where he was wounded. He relinquished his commission on 1 April 1920, retaining his rank of captain.[17]

Between 1919 and 1922 he was a Fellow of New College, Oxford, where he researched physiology and genetics. He then moved to the Cambridge University, where he accepted a readership in Biochemistry at Trinity College and taught until 1932.[8] From 1927 until 1937 he was also Head of Genetical Research at the John Innes Horticultural Institution.[18] During his nine years at Cambridge, Haldane worked on enzymes and genetics, particularly the mathematical side of genetics.[8] He was also the Fullerian Professor of Physiology at the Royal Institution from 1930 to 1932. In 1932 he was a visiting professor at the University of California at Berkeley. The next year in 1933 he was appointed as Professor of Genetics at University College London, where he spent most of his academic career.[19] Four years later he became the first Weldon Professor of Biometry at University College London.[8]

Physiology

Following his father's expertise, Haldane's earliest works were in the study of blood. His first scientific publication was on the mechanism of gaseous exchange by haemoglobin.[12] His subsequent works on the properties of blood became classic research.[20][21] He investigated several aspects of kidney functions and mechanism of excretion.[22][23]

In 1925, with G. E. Briggs, Haldane derived a new interpretation of the enzyme kinetics law described by Victor Henri in 1903, different from the 1913 Michaelis–Menten equation. Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten assumed that enzyme (catalyst) and substrate (reactant) are in fast equilibrium with their complex, which then dissociates to yield product and free enzyme. The Briggs–Haldane equation was of the same algebraic form, but their derivation is based on the quasi steady state approximation, that is the concentration of intermediate complex (or complexes) does not change. As a result, the microscopic meaning of the "Michaelis Constant" (Km) is different. Although commonly referring it as Michaelis–Menten kinetics, most of the current models actually use the Briggs–Haldane derivation.[24][25]

Genetics and evolution

Haldane made many contributions to genetics and was the first to demonstrate linkage in mammals,[26] as well as chicken.[27] He was one of the three major figures to develop the mathematical theory of population genetics. He is usually regarded as the third of these in importance, after R. A. Fisher and Sewall Wright. His greatest contribution was in a series of ten papers on "A Mathematical Theory of Natural and Artificial Selection", which was a major series of papers on the mathematical theory of natural selection. It treated many major cases for the first time, showing the direction and rates of changes of gene frequencies. It also pioneered in investigating the interaction of natural selection with mutation and with migration. Haldane's book, The Causes of Evolution (1932), summarised these results, especially in its extensive appendix. This body of work was a component of what came to be known as the "modern evolutionary synthesis", re-establishing natural selection as the premier mechanism of evolution by explaining it in terms of the mathematical consequences of Mendelian genetics.[28][29]

Haldane proposed the so-called "malaria hypothesis" in 1949 whereby he suggested that genetic disorders in humans living in malaria-endemic regions provide beneficial characters, and affected people are immune to malaria itself. He noted that red blood cell mutations such as sickle-cell anemia and various thalassemias were prevalent only in tropical regions where malaria was endemic. For example, most Africans did not suffer from malaria as would be expected. He predicted that such genetic disorders were favourable traits under natural selection that prevented individuals from malarial infection.[30] This concept of resistance to malaria was eventually confirmed by A.C. Allison in 1954.[31][32]

Haldane introduced many quantitative approaches in biology such as in his essay On Being the Right Size. His contributions to theoretical population genetics and statistical human genetics included the first methods using maximum likelihood for estimation of human linkage maps, and pioneering methods for estimating human mutation rates. He was the first to estimate rate of mutation in humans, at 2 × 10−5 mutations per gene per generation for the X-linked haemophilia gene, and to introduce the idea of a "cost of natural selection".[33] At John Innes he developed the complicated linkage theory for polyploids,[18] and extended the idea of gene/enzyme relationships with the biochemical and genetic study of plant pigments.

Haldane is also known for an observation from his essay On Being the Right Size, which Jane Jacobs and others have since referred to as Haldane's principle. This is that sheer size very often defines what bodily equipment an animal must have: "Insects, being so small, do not have oxygen-carrying bloodstreams. What little oxygen their cells require can be absorbed by simple diffusion of air through their bodies. But being larger means an animal must take on complicated oxygen pumping and distributing systems to reach all the cells." The conceptual metaphor to animal body complexity has been of use in energy economics and secession ideas.[34][35]

Origin of life

Haldane introduced the modern concept on the chemical origin of life. He propounded the theory in an eight-page article titled "The origin of life" in Rationalist Annual in 1929. According to Haldane's postulate the primitive ocean was a "vast chemical laboratory" containing a mixture of inorganic compounds – like a "hot dilute soup" (as imagined by Charles Darwin in 1871) – in which organic compounds could have formed. Under the solar energy the oxygenless atmosphere containing carbon dioxide, ammonia and water vapour gave rise to a variety of organic compounds, "living or half-living things". The first molecules reacted with one another to produce more complex compounds, and ultimately the cellular components. At some point a kind of "oily film" was produced that enclosed self-reproducing molecules, thereby becoming the first cell. J.D. Bernal named the hypothesis biopoiesis or biopoesis, the process of living matter evolving from self-replicating but nonliving molecules. The idea was generally dismissed as "wild speculation".[36] In 1924 Alexander Oparin had suggested similar idea in Russian, and in 1936 he introduced it to the English-speaking people. The experimental basis of the theory began in 1953 with the classic Miller–Urey experiment. Since then the primordial soup theory became a dominant theory in the chemistry of life, and often is attributed as Oparin-Haldane hypothesis.[37][38][39]

Experimentation

Haldane's first experiment, independent of his father, was with his sister Naomi. They started their work in 1908 investigating Mendelian genetics. They initially used guinea pigs, but switched to mice as experimental models. Their research titled "Reduplication in mice" was published in 1915, which became their first technical work in genetics.[26] He later preferred self-experimentation because he experienced that most of the time 'it is difficult to be sure how a rabbit feels at any time. Indeed, many rabbits make no serious attempt to cooperate with scientists'. Continuing his father's method, he would readily expose himself to danger to obtain data. To test the effects of acidification of the blood he drank dilute hydrochloric acid, enclosed himself in an airtight room containing 7% carbon dioxide, and found that it 'gives one a rather violent headache'. One experiment to study elevated levels of oxygen saturation triggered a fit which resulted in him suffering crushed vertebrae.[40] In his decompression chamber experiments, he and his volunteers suffered perforated eardrums, but, as Haldane stated in What is Life, "the drum generally heals up; and if a hole remains in it, although one is somewhat deaf, one can blow tobacco smoke out of the ear in question, which is a social accomplishment."[41]

Awards and honours

Haldane was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1932.[19] The French Government conferred him its National Order of the Legion of Honour in 1937. In 1952, he received the Darwin Medal from the Royal Society. In 1956, he was awarded the Huxley Memorial Medal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain. He received the Feltrinelli Prize from Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei in 1961. He also received an Honorary Doctorate of Science, an Honorary Fellowship at New College, and the Kimber Award of the US National Academy of Sciences. He was awarded the Linnean Society of London's prestigious Darwin–Wallace Medal in 1958.[42]

Marriage

In 1924, Haldane met Charlotte Burghes (née Franken), a young reporter for the Daily Express. So that they could marry, Charlotte divorced her husband, Jack Burghes, causing some controversy. Haldane was almost dismissed from Cambridge for the way he handled his meeting with her, which led to the divorce. They married in 1926. Following their separation in 1942, the Haldanes divorced in 1945. He later married Helen Spurway.

Political views

Haldane became a socialist during the First World War, supported the Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War, and finally became a Communist. He was an enthusiastic, dialectical materialist Marxist, and wrote many articles in the Communist Daily Worker. He was the chairman of the editorial board of the London edition from 1940 to 1949. His vision of the socialist principle can be considered pragmatic. In On Being the Right Size, Haldane doubted that socialism could be operated on the scale of the British Empire or the United States or, implicitly, the Soviet Union: "while nationalization of certain industries is an obvious possibility in the largest of states, I find it no easier to picture a completely socialized British Empire or United States than an elephant turning somersaults or a hippopotamus jumping a hedge."

In 1937, Haldane became a marxist and an open supporter of the Communist Party, although not a member of the party. In 1938, he proclaimed enthusiastically that "I think that Marxism is true." He joined the Communist Party of Great Britain in 1942. The first edition of his children's book My Friend Mr. Leakey contained an avowal of his party membership which was removed from later editions. Events in the Soviet Union, such as the rise of Trofim Lysenko and the crimes of Joseph Stalin, may have caused him to break with the Party later in life, although he showed a partial support of Lysenko and Stalin. Pressed to speak out about the rise of Lysenkoism and the persecution of geneticists in the Soviet Union as anti-Darwinist and the denouncement of genetics as incompatible with dialectical materialism, Haldane shifted the focus to the United Kingdom and a criticism of the dependence of scientific research on financial patronage. In 1941 Haldane wrote about the Soviet trial of his friend and fellow geneticist Nikolai Vavilov:

| “ | The controversy among Soviet geneticists has been largely one between the academic scientist, represented by Vavilov and interested primarily in the collection of facts, and the man who wants results, represented by Lysenko. It has been conducted not with venom, but in a friendly spirit. Lysenko said (in the October discussions of 1939): 'The important thing is not to dispute; let us work in a friendly manner on a plan elaborated scientifically. Let us take up definite problems, receive assignments from the People's Commissariat of Agriculture of the USSR and fulfil them scientifically. Soviet genetics, as a whole, is a successful attempt at synthesis of these two contrasted points of view.' | ” |

His ambiguous attitude toward the persecution of Vavilov was explicable by the atmosphere of the period, where supporters of communism needed to be unequivocal. Haldane's attitude changed dramatically at the end of the Second World War, when Lysenkoism reached a totalitarian influence in the Communist movement. He then became an explicit critic of the regime. He left the party in 1950, shortly after considering standing for Parliament as a Communist Party candidate. He continued to admire Stalin, describing him in 1962 as "a very great man who did a very good job".

India

In 1956, Haldane left his post at University College London, and moved to Calcutta, where he joined the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI).[43] Haldane's move to India was influenced by a number of factors. Officially he stated that his chief political reason was in response to the Suez Crisis. He wrote: "Finally, I am going to India because I consider that recent acts of the British Government have been violations of international law." His interest in India was also because of his interest in biological research as he believed that the warm climate would do him good, and that India offered him freedom and shared his socialist dreams.[44] One immediate factor was related to a police case involving his wife Helen, who was arrested on charges of misbehaviour due to excessive drinking and refusal to pay fine. The university sacked her and Haldane followed suit. On his lighter side his "reason for settling in India was to avoid wearing socks," and he concluded, "Sixty years in socks is enough."[45] This could be partly true because Haldane always dressed up in Indian clothes, and was often mistaken to be a Hindu priest or guru.[2]

At the ISI, he headed the biometry unit and spent time researching a range of topics and guiding other researchers around him. He was keenly interested in inexpensive research and he wrote to Julian Huxley about his observations on Vanellus malabaricus, the Yellow-wattled Lapwing, boasting that he observed them from the comfort of his backyard. Haldane took an interest in anthropology, human genetics and botany. He advocated the use of Vigna sinensis (cowpea) as a model for studying plant genetics. He took an interest in the pollination of the common weed Lantana camara. The quantitative study of biology was his focus and he lamented that Indian universities forced those who took up biology to give up on an education in mathematics.[46] Haldane took an interest in the study of floral symmetry. His wife, Helen Spurway, conducted studies on wild silk moths.[44] In January 1961 they befriended the young Canadian lepidopterist Gary Botting, who initially visited the Indian Statistical Institute to share the results of his experiments hybridising silk moths of the genus Antheraea. Uncomfortable with Haldane's "communist" sympathies, the United States cultural attache, Duncan Emery, summarily cancelled Gary Botting's attendance at a high-profile banquet to which the Haldanes had invited him to meet biologists from all over India. Haldane protested this "insult" by going on a much-publicized hunger strike.[47][48] When the director of the I.S.I., P. C. Mahalanobis, confronted Haldane about both the hunger strike and the unbudgeted banquet, Haldane resigned his post (in February 1961) and moved to a newly established biometry unit in Odisha.[44]

Haldane eventually became an Indian citizen.[43] He was also interested in Hinduism and after his arrival he became a vegetarian and started wearing Indian clothes.[44] In Kolkata, the busy connecting road from Eastern Metropolitan Bypass to Park Circus area on which the Science City is located, is named after him. In 1961, Haldane described India as "the closest approximation to the Free World." His American friend, Jerzy Neyman, a professor of Statistics in the University of California, Berkeley, objected to this premise. Neyman gave his impression that "India has its fair share of scoundrels and a tremendous amount of poor unthinking and disgustingly subservient individuals who are not attractive."[43] Haldane retorted:

| “ | Perhaps one is freer to be a scoundrel in India than elsewhere. So one was in the U.S.A in the days of people like Jay Gould, when (in my opinion) there was more internal freedom in the U.S.A than there is today. The "disgusting subservience" of the others has its limits. The people of Calcutta riot, upset trams, and refuse to obey police regulations, in a manner which would have delighted Jefferson. I don't think their activities are very efficient, but that is not the question at issue. | ” |

When on 25 June 1962, six years after Haldane's move to India, he was described in print as a "Citizen of the World" by an American science writer, Groff Conklin, Haldane's response was as follows:[43]

| “ | No doubt I am in some sense a citizen of the world. But I believe with Thomas Jefferson that one of the chief duties of a citizen is to be a nuisance to the government of his state. As there is no world state, I cannot do this. On the other hand, I can be, and am, a nuisance to the government of India, which has the merit of permitting a good deal of criticism, though it reacts to it rather slowly. I also happen to be proud of being a citizen of India, which is a lot more diverse than Europe, let alone the U.S.A, the U.S.S.R or China, and thus a better model for a possible world organisation. It may of course break up, but it is a wonderful experiment. So, I want to be labeled as a citizen of India. | ” |

Author and visionary

Haldane was a famous science populariser. His essay Daedalus; or, Science and the Future (1924) was remarkable in predicting many scientific advances but has been criticised for presenting a too idealistic view of scientific progress. Haldane’s book shows the effect of the separation between sexual life and pregnancy as a satisfactory one on human psychology and social life. The book was regarded as shocking science fiction at the time, being the first book about ectogenesis (the development of foetuses in artificial wombs) - "test tube babies", brought to life without sexual intercourse or pregnancy. His book, A.R.P. (Air Raid Precautions) (1938) combined his physiological research into the effects of stress upon the human body with his experience of air raids during the Spanish Civil War to provide a scientific explanation of the air raids that Britain was to endure during the Second World War, then imminent. Haldane wrote many popular essays on science; in 1927 these were collected and published in a volume titled Possible Worlds.

Haldane was a friend of the author Aldous Huxley, who parodied him in the novel Antic Hay (1923) as Shearwater, "the biologist too absorbed in his experiments to notice his friends bedding his wife". Haldane's discourse in Daedalus on ectogenesis was an influence on Huxley's Brave New World (1932) which features a eugenic society. Haldane's work was also admired by Gerald Heard.[49]

Haldane was one of those, along with Olaf Stapledon, Charles Kay Ogden, I. A. Richards, and H. G. Wells, whom C. S. Lewis accused of scientism, "the belief that the supreme moral end is the perpetuation of our own species, and that this is to be pursued even if, in the process of being fitted for survival, our species has to be stripped of all those things for which we value it—of pity, of happiness, and of freedom." Shortly after the third book of the Ransom Trilogy appeared, J.B.S. Haldane criticised the entire work in an article titled "Auld Hornie, F.R.S.". The title reflects the sarcastic tone of the article, Auld Hornie being the pet name given to the devil by the Scots and F.R.S. standing for "Fellow of the Royal Society". In the essay, Haldane attacked Lewis for scientific inaccuracies, as well as what Haldane saw as Lewis' "complete mischaracterisation of science, and his disparagement of the human race".[50] Lewis’s response, "A Reply to Professor Haldane", was never published during his lifetime and apparently never seen by Haldane. In it, Lewis claims that he was attacking scientism, not scientists, by challenging the view of some that the supreme goal of our species is to perpetuate itself at any expense.

Haldane wrote a popular book for children titled My Friend Mr Leakey (first published in 1937) which contained the stories "A Meal With a Magician", "A Day in the Life of a Magician", "Mr Leakey's Party", "Rats", "The Snake with the Golden Teeth", and "My Magic Collar Stud". It was reprinted several times – in 1944, 1971, and 1972 with illustrations by Quentin Blake. When he appears as a character in the stories, several of which are written in the first person, he describes his job as a professor, or: "Doing sums to make new kinds of primroses and cats".

Haldane edited Gary Botting's manuscript on the genetics of giant silk moths with marginal notes. In his preface to The Orwellian World of Jehovah's Witnesses, Dr. Botting wrote that when he was a teenager Haldane showed him many species of birds.[51] Botting credited Haldane with throwing him a "lifeline" in the form of a demonstrable manifestation of Darwinian evolution, which, decades later, "rescued" him from the perils of religious fundamentalism, in particular creationism, that he had faced in his youth. Half a century later, Botting still regarded his visit with J. B. S. Haldane and Helen Spurway as the single most influential existential experience of his life.[52]

In 1923, in a talk given in Cambridge titled "Science and the Future", Haldane, foreseeing the exhaustion of coal for power generation in Britain, proposed a network of hydrogen-generating windmills. This is the first proposal of the hydrogen-based renewable energy economy.[53][54][55]

In his An Autobiography in Brief, written shortly before his death in India, Haldane named four close associates as those showing promise to become illustrious scientists: T. A. Davis, K. R. Dronamraju, S. D. Jayakar and S. K. Roy.[56]

Haldane was the first to have thought the genetic basis of creating identical copies of humans, and eventually super-talented individuals. For this he coined the term "clone", deriving it from a Greek word klon, which means "twig".[57] He introduced the term in his speech on “Biological Possibilities for the Human Species of the Next Ten Thousand Years” at the Ciba Foundation Symposium on Man and his Future in 1963.[58][59]

Death

Shortly before his death from cancer, Haldane wrote a comic poem while in the hospital, mocking his own incurable disease; it was read by his friends, who appreciated the consistent irreverence with which Haldane had lived his life. The poem first appeared in print in the 21 February 1964 issue of The New Statesman, and runs:[60][61]

"Cancer’s a Funny Thing:

I wish I had the voice of Homer

To sing of rectal carcinoma,

This kills a lot more chaps, in fact,

Than were bumped off when Troy was sacked..."

The poem ends:

"... I know that cancer often kills,

But so do cars and sleeping pills;

And it can hurt one till one sweats,

So can bad teeth and unpaid debts.

A spot of laughter, I am sure,

Often accelerates one’s cure;

So let us patients do our bit

To help the surgeons make us fit."

Haldane died on 1 December 1964. He willed that his body be used for study at the Rangaraya Medical College, Kakinada.[42]

| “ |

"My body has been used for both purposes during my lifetime and after my death, whether I continue to exist or not, I shall have no further use for it, and desire that it shall be used by others. Its refrigeration, if this is possible, should be a first charge on my estate."[62] |

” |

Quotations

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: J. B. S. Haldane |

- He is famous for the (possibly apocryphal) response that he gave when some theologians asked him what could be inferred about the mind of the Creator from the works of His Creation: "An inordinate fondness for beetles."[63] This is in reference to there being over 400,000 known species of beetles in the world, and that this represents 40% of all known insect species (at the time of the statement, it was over half of all known insect species).[64]

- Often quoted for saying, "My own suspicion is that the universe is not only queerer than we suppose, but queerer than we can suppose."[65]

- "It seems to me immensely unlikely that mind is a mere by-product of matter. For if my mental processes are determined wholly by the motions of atoms in my brain I have no reason to suppose that my beliefs are true. They may be sound chemically, but that does not make them sound logically. And hence I have no reason for supposing my brain to be composed of atoms."[66]

- "Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist: he cannot live without her but he's unwilling to be seen with her in public."[67][68]

- "I had gastritis for about fifteen years until I read Lenin and other writers, who showed me what was wrong with our society and how to cure it. Since then I have needed no magnesia."[69]

- "I suppose the process of acceptance will pass through the usual four stages: i) This is worthless nonsense, ii) This is an interesting, but perverse, point of view, iii) This is true, but quite unimportant, iv) I always said so."[70]

- "Three hundred and ten species in all of India, representing two hundred and thirty-eight genera, sixty-two families, nineteen different orders. All of them on the Ark. And this is only India, and only the birds."[51]

- When asked whether he would lay down his life for his brother, Haldane, preempting Hamilton's Rule, supposedly replied "two brothers or eight cousins".[71]

Publications

- Daedalus; or, Science and the Future (1924), E. P. Dutton and Company, Inc., a paper read to the Heretics, Cambridge, on 4 February 1923

- second edition (1928), London: Kegan Paul, Trench & Co.

- see also Haldane's Daedalus Revisited (1995), ed. with an introd. by Krishna R. Dronamraju, Foreword by Joshua Lederberg; with essays by M. F. Perutz, Freeman Dyson, Yaron Ezrahi, Ernst Mayr, Elof Axel Carlson, D. J. Weatherall, N. A. Mitchison and the editor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854846-X

- A Mathematical Theory of Natural and Artificial Selection, a series of papers beginning in 1924

- G. E. Briggs and J. B. S. Haldane (1925). A note on the kinetics of enzyme action, Biochemistry Journal., vol. 19: 338–339

- Callinicus: A Defence of Chemical Warfare (1925), E. P. Dutton

- Possible Worlds and Other Essays (1928), Harper and Brothers. 1937 edition London: Chatto & Windus. 2001 edition Transaction Publishers: ISBN 0-7658-0715-7 (includes On Being the Right Size)

- Animal Biology (1929) Oxford: Clarendon

- Enzymes (1930), MIT Press 1965 edition with new preface by the author written just prior to his death: ISBN 0-262-58003-9

- The Inequality of Man, and Other Essays (1932)

- The Causes of Evolution (1932)

- Science and Human Life (1933), Harper and Brothers, Ayer Co. reprint: ISBN 0-8369-2161-5

- Science and the Supernatural: Correspondence with Arnold Lunn (1935), Sheed & Ward, Inc,

- Fact and Faith (1934), Watts Thinker's Library[72]

- "A Contribution to the Theory of Price Fluctuations", The Review of Economic Studies, 1:3, 186-195 (1934).

- My Friend Mr Leakey (1937), Vigyan Prasar 2001 reprint: ISBN 81-7480-029-8

- Air Raid Precautions (A.R.P.) (1938), Victor Gollancz

- Marxist Philosophy and the Sciences (1939), Random House, Ayer Co. reprint: ISBN 0-8369-1137-7

- Science and Everyday Life (1940), Macmillan, 1941 Penguin, Ayer Co. 1975 reprint: ISBN 0-405-06595-7

- Science in Peace and War (1941), Lawrence & Wishart Ltd

- New Paths in Genetics (1941), George Allen & Unwin

- Heredity & Politics (1943), George Allen & Unwin

- Why Professional Workers should be Communists (1945), London: Communist Party (of Great Britain) In this four page pamphlet, Haldane contends that Communism should appeal to professionals because Marxism is based on the scientific method and Communists hold scientists as important; Haldane subsequently disavowed this position.

- Adventures of a Biologist (1947)

- Science Advances (1947), Macmillan

- What is Life? (1947), Boni and Gaer, 1949 edition: Lindsay Drummond

- Everything Has a History (1951), Allen & Unwin—Includes "Auld Hornie, F.R.S."; C.S. Lewis's "Reply to Professor Haldane" is available in "On Stories and Other Essays on Literature," ed. Walter Hooper (1982), ISBN 0-15-602768-2.

- "The Origins of Life", New Biology, 16, 12–27 (1954). Suggests that an alternative biochemistry could be based on liquid ammonia.

- "Origin of Man", Nature, 176, 169 (1955).

- "Cancer's a Funny Thing", New Statesman, 21 February 1964.

See also

- List of independent discoveries ("primordial soup" theory of the evolution of life from carbon-based molecules, ca. 1924)

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- Experiments in the Revival of Organisms, a 1940 Soviet film featuring Haldane in the introduction.

- Haldane's Rule

Bibliography

- Bryson, Bill (2003) A Short History of Nearly Everything pp. 300–302; ISBN 0-552-99704-8

- Clark, Ronald (1968) JBS: The Life and Work of J.B.S. Haldane ISBN 0-340-04444-6

- Dronamraju, K. R. (editor) (1968) Haldane and Modern Biology Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, Maryland.

- Dronamraju, K. R. (1985) Haldane. The life and work of J B S Haldane with special reference to India. Aberdeen University Press. Foreword by Naomi Mitchison.

- Geoffrey Zubay et al., Biochemistry (2nd ed., 1988), enzyme kinetics, pp. 266–272; MacMillan, New York ISBN 0-02-432080-3

References

- ↑ Pirie, N. W. (1966). "John Burdon Sanderson Haldane. 1892-1964". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society 12 (0): 218–249. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1966.0010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dronamraju, KR (1992). "J.B.S. Haldane (1892-1964): centennial appreciation of a polymath". American Journal of Human Genetics 51 (4): 885–9. PMC 1682816. PMID 1415229.

- ↑ Dawkins, [edited by] Richard (2008). The Oxford Book of Modern Science Writing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-19-921680-0.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (2011). The Lying Stones of Marrakech : Penultimate Reflections in Natural History (1st Harvard University Press ed. ed.). Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 305. ISBN 9780674061675.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C. "[Foreword on] What I Require From Life". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Clarke, Arthur C. (2009). "Foreword". In John Burdon Sanderson Haldane. What I Require From Life: Writings on Science and Life from J.B.S. Haldane. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. ix. ISBN 9780199237708.

- ↑ Yount, Lisa (2003). A to Z of Biologists. New York, NY: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 113–115. ISBN 9781438109176.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Acott, C. (1999). "JS Haldane, JBS Haldane, L Hill, and A Siebe: A brief resumé of their lives.". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal 29 (3). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Hedrick, Larry (1989). "J.B.S. Haldane: A Legacy in Several Worlds". The World & I Online.

- ↑ Haldane, J. B. S., Fact and Faith. London: London, Watts & Co., 1934.

- ↑ "J. S. Haldane (1860–1936)". Oxfordshire Blue Plaques Board. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Douglas, CG; Haldane, JS; Haldane, JB (1912). "The laws of combination of haemoglobin with carbon monoxide and oxygen". The Journal of Physiology 44 (4): 275–304. PMC 1512793. PMID 16993128.

- ↑ Dronamraju, Krishna (2011). Haldane, Mayr, and beanbag genetics. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 9780199813346.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 29172. p. 5081. 25 May 1915. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 29172. p. 5079. 25 May 1915. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 29399. p. 12410. 10 December 1915. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 32445. p. 7036. 2 September 1921. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 https://www.jic.ac.uk/centenary/timeline/info/JBSHaldane.htm

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Full view of record [of Haldane]". UCL Archives. University of California at Berkeley. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Davies, HW; Haldane, JB; Kennaway, EL (1920). "Experiments on the regulation of the blood's alkalinity: I". The Journal of Physiology 54 (1-2): 32–45. PMC 1405746. PMID 16993473.

- ↑ Haldane, JB (1921). "Experiments on the regulation of the blood's alkalinity: II". The Journal of Physiology 55 (3-4): 265–75. PMC 1405425. PMID 16993510.

- ↑ Baird, MM; Haldane, JB (1922). "Salt and water elimination in man". The Journal of Physiology 56 (3-4): 259–62. PMC 1405382. PMID 16993567.

- ↑ Davies, HW; Haldane, JB; Peskett, GL (1922). "The excretion of chlorides and bicarbonates by the human kidney". The Journal of Physiology 56 (5): 269–74. PMC 1405381. PMID 16993528.

- ↑ Briggs, GE; Haldane, JB (1925). "A Note on the Kinetics of Enzyme Action". The Biochemical journal 19 (2): 338–9. PMC 1259181. PMID 16743508.

- ↑ Chen, W. W.; Niepel, M.; Sorger, P. K. (2010). "Classic and contemporary approaches to modeling biochemical reactions". Genes & Development 24 (17): 1861–1875. doi:10.1101/gad.1945410. PMC 2932968. PMID 20810646.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Haldane, J. B. S.; Sprunt, A. D.; Haldane, N. M. (1915). "Reduplication in mice (Preliminary Communication)". Journal of Genetics 5 (2): 133–135. doi:10.1007/BF02985370.

- ↑ Haldane, JB (1921). "Linkage in poultry". Science 54 (1409): 663. doi:10.1126/science.54.1409.663. PMID 17816160.

- ↑ Haldane, JB (1990). "A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection--I. 1924". Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 52 (1-2): 209–40; discussion 201–7. doi:10.1016/s0092-8240(05)80010-2. PMID 2185859.

- ↑ Haldane, JB (1959). "The theory of natural selection today". Nature 183 (4663): 710–3. doi:10.1038/183710a0. PMID 13644170.

- ↑ Sabeti, Pardis C (2008). "Natural selection: uncovering mechanisms of evolutionary adaptation to infectious disease". Nature Education 1 (1): 13.

- ↑ Allison, AC (1954). "The distribution of the sickle-cell trait in East Africa and elsewhere, and its apparent relationship to the incidence of subtertian malaria". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 48 (4): 312–8. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(54)90101-7. PMID 13187561.

- ↑ Hedrick, Philip W (2012). "Resistance to malaria in humans: the impact of strong, recent selection". Malaria Journal 11 (1): 349. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-11-349. PMC 3502258. PMID 23088866.

- ↑ Haldane, J. B. S. (1935). "The rate of spontaneous mutation of a human gene". Journal of Genetics 31 (3): 317–326. doi:10.1007/BF02982403.

- ↑ Marvin, Stephen (2012). Dictionary of Scientific Principles. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. p. 140. ISBN 9781118582244.

- ↑ Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee (2009). Putting science and engineering at the heart of Government policy : eighth report of session 2008-09 1. London: The Stationery Office. p. 40. ISBN 9780215540348.

- ↑ Fry, Iris (2000). The Emergence of Life on Earth: A Historical and Scientific Overview. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 65–66, 71–74. ISBN 9780813527406.

- ↑ Gordon-Smith, Chris. "The Oparin-Haldane Hypothesis". Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ "The Oparin-Haldane Theory of the Origin of Life". Department of Chemistry, University of Oxford. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ Lazcano, A. (2010). "Historical development of origins research". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2 (11): a002089–a002089. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a002089. PMC 2964185. PMID 20534710.

- ↑ Jobling MA (2012). "The unexpected always happens". Investigative Genetics 3 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-3-5. PMC 3298498. PMID 22357349.

- ↑ Bryson, Bill. "A Short History Of Nearly Everything". 1st. New York: Broadway Books, 2003. at Googlebooks

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Mahanti, Subodh. "John Burdon Sanderson Haldane: The Ideal of a Polymath". Vigyan Prasar Science Portal. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy, Ramachandra Guha, Pan Macmillan, 2008, pp. 769 - 770

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Krishna R. Dronamraju (1987). "On Some Aspects of the Life and Work of John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, F.R.S., in India". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 41 (2): 211–237. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1987.0006. JSTOR 531546. PMID 11622022.

- ↑ deJong-Lambert, William (2012). The Cold War Politics of Genetic Research: An Introduction to the Lysenko Affair (2012. ed.). Dordrecht: Springer. p. 150. ISBN 9789400728394.

- ↑ Majumder PP (1998). "Haldane's Contributions to Biological Research in India" (PDF). Resonance 3 (12): 32–35. doi:10.1007/BF02838095.

- ↑ "Haldane on Fast: Insult by USIS Alleged," Times of India, 19 January 1961; "Protest Fast by Haldane: USIS’s "Anti-Indian Activities," Times of India, 18 January 1961; "Situation was Misunderstood, Scholars Explain," Times of India, 20 January 1961; "USIS Explanation does not satisfy Haldane: Protest fast continues," Times of India, 18 January 1961; "USIS Claim Rejected by Haldane: Protest Fast to Continue," Times of India, 18 January 1961; "Haldane Not Satisfied with USIS Apology: Fast to Continue," Free Press Journal, 18 January 1961; "Haldane Goes on Fast In Protest Against U.S. Attitude," Times of India, 18 January 1961; "Haldane to continue fast: USIS explanation unsatisfactory," Times of India, 19 January 1961; "Local boy in hunger strike row," Toronto Star, 20 January 1961; "Haldane, Still on Fast, Loses Weight: U.S.I.S. Act Termed 'Discourteous'," Indian Express, 20 January 1961; "Haldane Slightly Tired on Third Day of Fast," Times of India, 21 January 1961; "Haldane Fasts for Fourth Consecutive Day," Globe and Mail, 22 January 1961

- ↑ Botting, Gary (1984). "Preface". In Heather Denise Harden and Gary Botting. The Orwellian World of Jehovah's Witnesses. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. xvii. ISBN 9780802065452.

- ↑ "Mr. Wells' Apocalypse" by Gerald Heard. The Nineteenth Century, October 1933. Reprinted in The H. G. Wells Scrapbook by Peter Haining. London : New English Library, 1978. ISBN 0450037789 (pp. 108-114).

- ↑ Adams, Mark B., "The Quest for Immortality: Visions and Presentiments in Science and Literature", in Post, Stephen G., and Binstock, Robert H., The Fountain of Youth:Cultural, Scientific, and Ethical Perspectives on a Biomedical Goal. Oxford University Press, 2004; ISBN 0195170083 (p. 57-58).

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Botting, Gary (1984). "Preface". The Orwellian World of Jehovah's Witnesses. p. xvi.

- ↑ Tihemme Gagnon, "Introduction," Streaking! The Collected Poems of Gary Botting, Miami: Strategic, 2013.

- ↑ "An Early Vision of Transhumanism, and the First Proposal of a Hydrogen-Based Renewable Energy Economy". Jeremy Norman & Co., Inc. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Hordeski, Michael Frank (2009). Hydrogen & Fuel Cells: Advances in Transportation and Power. Lilburn, GA: The Fairmont Press, Inc. pp. 202–203. ISBN 9780881735628.

- ↑ Demirbas, Ayhan (2009). Biohydrogen For Future Engine Fuel Demands (Online-Ausg. ed.). London: Springer London. p. 106. ISBN 9781848825116.

- ↑ "Selected Genetic Papers of JBS Haldane", pp. 19–24, New York: Garland, 1990

- ↑ Thomas, Isabel (2013). Should scientists pursue cloning?. London: Raintree. p. 5. ISBN 9781406233919.

- ↑ Haldane, J.B.S. (1963). "Biological Possibilities for the Human Species in the Next Ten Thousand Years". In Wolstenholme, Gordon. Man and his future. London: J. & A. Churchill. doi:10.1002/9780470715291.ch22. ISBN 9780470714799.

- ↑ Haldane, J.B.S. "Biological Possibilities for the Human Species in the Next Ten Thousand Years". World Transhumanist Association. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Dronamraju, K. (2010). "J. B. S. Haldane's last years: his life and work in India (1957-1964)". Genetics 185 (1): 5–10. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.116632. PMC 2870975. PMID 20516291.

- ↑ Hesketh, Robin (2012). Betrayed by Nature: The War on Cancer. New York (US): Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 237–238. ISBN 978-0-230-34192-0.

- ↑ Murty, K. Krishna (2005). Spice in science. Dehli: Pustak Mahal. p. 68. ISBN 978-81-223-0900-3. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ↑ Hutchinson, G. Evelyn (1959). "Homage to Santa Rosalia or Why Are There So Many Kinds of Animals?". The American Naturalist 93 (870): 145–159. doi:10.1086/282070. JSTOR 2458768.

- ↑ Stork, Nigel E. (June 1993). "How many species are there?" (PDF). Biodiversity and Conservation 2 (3): 215–232. doi:10.1007/BF00056669. ISSN 0960-3115. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ↑ Haldane, J.B.S., Possible Worlds: And Other Essays [1927], Chatto and Windus: London, 1932, reprint, p.286. Emphasis in the original.

- ↑ Haldane, J.B.S., Possible Worlds: And Other Essays [1927], Chatto and Windus: London, 1932, reprint, p.209.

- ↑ Hull, D., Philosophy of Biological Science, Foundations of Philosophy Series, Prentice–Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N. J., 1973.

- ↑ Mayr, Ernst (1974) Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Volume XIV, pages 91–117.

- ↑ Smith, J.B.S. Haldane ; edited by John Maynard (1985). On being the right size and other essays (Repr ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780192860453.

- ↑ Haldane, J.B.S. (1963). "[Book review] The Truth About Death: The Chester Beatty Research Institute Serially Abridged Life Tables, England and Wales, 1841-1960" (PDF). Journal of Genetics 58 (3): 464.

- ↑ Dugatkin, LA (2007). "Inclusive fitness theory from Darwin to Hamilton". Genetics 176 (3): 1375–80. PMC 1931543. PMID 17641209.

- ↑ Fact and faith, [WorldCat.org]

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: J. B. S. Haldane |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to J. B. S. Haldane. |

- An online copy of Daedalus or Science and the Future

- A review (from a modern perspective) of The Causes of Evolution

- Unofficial SJG Archive – People – JBS Haldane (1892–1964) Accessed 22 February 2006. Useful text but the likeness is not of JBS but of his father John Scott Haldane.

- Haldane's contributions to science in India

- Marxist Writers: J.B.S. Haldane

There are photographs of Haldane at

- JBS Haldane, on the Portraits of Statisticians page.

The biography on the Marxist Writers page has a photograph of Haldane when younger.

- My Friend Mr. Leakey – text – Haldane's most amusing imaginary acquaintance

- Codebreakers: Makers of Modern Genetics: the J B S Haldane papers

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Julian Huxley |

Fullerian Professor of Physiology 1930 – 1933 |

Succeeded by Grafton Elliot Smith |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|