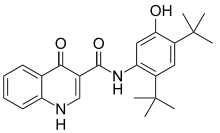

Ivacaftor

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

| N-(2,4-Di-tert-butyl-5-hydroxyphenyl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide | |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Kalydeco |

| Licence data | US FDA:link |

| |

| |

| Oral | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 99% |

| Metabolism | CYP3A |

| Half-life | 12 hrs (single dose) |

| Excretion | 88% faeces |

| Identifiers | |

|

873054-44-5 | |

| R07AX02 | |

| PubChem | CID 16220172 |

| ChemSpider |

17347474 |

| UNII |

1Y740ILL1Z |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:66901 |

| Synonyms | VX-770 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C24H28N2O3 |

| 392.490 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

Ivacaftor (trade name Kalydeco, developed as VX-770) is a drug approved for patients with a certain mutation of cystic fibrosis, which accounts for 4–5% cases of cystic fibrosis.[1][2] Ivacaftor was developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals in conjunction with the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and is the first drug that treats the underlying cause rather than the symptoms of the disease.[3] Called "the most important new drug of 2012",[4] and "a wonder drug"[5] it is one of the most expensive drugs, costing over US$300,000 per year, which has led to criticism of Vertex for the high cost.

Cystic fibrosis is caused by any one of several defects in a protein, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which regulates fluid flow within cells and affects the components of sweat, digestive fluids, and mucus. One such defect is the G551D mutation, in which the amino acid glycine (G) in position 551 is replaced with aspartic acid (D). G551D is characterized by a dysfunctional CFTR protein on the cell surface. In the case of G551D, the protein is trafficked to the correct area, the epithelial cell surface, but once there the protein cannot transport chloride through the channel. Ivacaftor, a CFTR potentiator, improves the transport of chloride through the ion channel by binding to the channels directly to induce a non-conventional mode of gating which in turn increases the probability that the channel is open.[6][7][8]

Medical Uses

Ivacaftor is used for the treatment of cystic fibrosis in persons having one of several specifics mutations in the CFTR protein including G551D, G1244E, G1349D, G178R, G551S, S1251N, S1255P, S549N,or S549R.[9]

G551D Mutation

Of the approximately 70,000 cases of cystic fibrosis worldwide, 4% (~3,000) are due to a mutation called G551D.[10][11] The safety and efficacy of ivacftor for the treatment of cystic fibrosis in patients with this mutation was examined in 2 clinical trials.

The first trial was performed in adults having baseline respiratory function (FEV1) between 32% and 98% of normal for persons of similar age, height, and weight. The baseline average was 64%. Improvement in FEV1 was rapid and sustained. At the end of 48 weeks, people treated with ivacaftor had on average an absolute increase in FEV1 of 10.4%, vs. a decline of 0.2% in the placebo group. Pulmonary exacerbations were reduced by about half in the ivacaftor group relative to the placebo group.[12]

In a second trial conducted in children age 6 to 11, the average improvement in FEV1 was an absolute increase of 12.5% in the ivacaftor group at 48 weeks, compared to a very slight decline in the placebo group.[13]

Ivacaftor is approved for use in cystic fibrosis patients in the US, Canada[14] and across some European countries. The US Food and Drug Administration approved ivacaftor in January 2012 and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) followed soon after.[15][16]

G1244E, G1349D, G178R, G551S, S1251N, S1255P, S549N, and S549R mutations

A third clinical trial examined the effiacy of ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis due to G1244E, G1349D, G178R, G551S, S1251N, S1255P, S549N, or S549R mutations. This trial, which included 39 people of age greater than 6 years, used a crossover design. The people in the trial had FEV1 averaging 78% of normal at basline. The people in the trial were randomized to receive either ivacaftor or placebo for 8 weeks. This was followed by a 4 to 8 week washout period, then each group received the opposite treatment from what it received in the first part of the trial. At Week 8, the people on treatment with ivacaftor experienced an average absolute improvement in FEV1 of 13.8%, but there was a strong dependence of the efficacy on the exact mutation that a patient had. The detailed data for different mutation types is shown in the U.S package insert.[17]

Adverse effects

The most common adverse reactions experienced by patients who received ivacaftor in the pooled placebo-controlled Phase 3 studies were abdominal pain (15.6% versus 12.5% on placebo), diarrhoea (12.8% versus 9.6% on placebo), dizziness (9.2% versus 1.0% on placebo), rash (12.8% versus 6.7% on placebo), upper respiratory tract reactions (including upper respiratory tract infection, nasal congestion, pharyngeal erythema, oropharyngeal pain, rhinitis, sinus congestion, and nasopharyngitis) (63.3% versus 50.0% on placebo), headache (23.9% versus 16.3% on placebo) and bacteria in sputum (7.3% versus 3.8% on placebo). One patient in the ivacaftor group reported a serious adverse reaction: abdominal pain.[16]

Pharmacokinetics

Distribution

Ivacaftor is approximately 99% bound to plasma proteins, primarily to alpha 1-acid glycoprotein and albumin. Ivacaftor does not bind to human red blood cells.[16]

Biotransformation

Ivacaftor is extensively metabolised in humans. In vitro and in vivo data indicate that ivacaftor is primarily metabolised by CYP3A. M1 and M6 are the two major metabolites of ivacaftor in humans. M1 has approximately one-sixth the potency of ivacaftor and is considered pharmacologically active. M6 has less than one-fiftieth the potency of ivacaftor and is not considered pharmacologically active.[16]

Elimination

Following oral administration, the majority of ivacaftor (87.8%) is eliminated in the faeces after metabolic conversion. The major metabolites M1 and M6 accounted for approximately 65% of total dose eliminated with 22% as M1 and 43% as M6. There was negligible urinary excretion of ivacaftor as unchanged parent. The apparent terminal half-life was approximately 12 hours following a single dose in the fed state. The apparent clearance (CL/F) of ivacaftor was similar for healthy subjects and patients with CF. The mean (±SD) of CL/F for the 150 mg dose was 17.3 (8.4) L/h in healthy subjects at steady state.[16]

Pharmacokinetics

Ivacaftor acts a chaperone for the CFTR protein and helps it reach the membrane when it otherwise would not.

Economics

The cost of ivacaftor is $311,000 per year, roughly similar to the price of other drugs for extremely rare diseases.[18] In the first 9 months of its second year on the market (2014), ivacaftor sales were $339M, representing 54% of Vertex's product sales revenue. During the same period, drug development expenses were $458M, most of which was spent on cystic fibrosis-related research.[19]

An editorial in JAMA called the price of ivacaftor "exorbitant", citing the support by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation in its development and the contribution made by fundamental scientific research performed by the National Institutes of Health and relied upon by Vertex in its cystic fibrosis drug discovery programs.[20] The company responded in an email that "while publicly funded academic research provided important early understanding of the cause of cystic fibrosis, it took Vertex scientists 14 years of their own research, funded mostly by the company, before the drug won approval."[21]

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to improving healthcare for people with cystic fibrosis, provided $150 million of the funding for the development for ivacaftor in exchange for royalty rights in the event that the drug was successfully developed and commercialized. In 2014, the Foundation sold these royalty rights for $3.3 billion. The Foundation has stated that it intends to spend these funds in support of further research.[22][23]

Vertex said it would make the drug available free to patients in the United States with no insurance and a household income of under $150,000.[24] In 2012, 24 US doctors and researchers involved in the development of the drug wrote to Vertex to protest the price of the drug, which had been set at about $300,000 per year. In the UK, the company provided the drug free for a limited time for certain patients, then left the hospitals to decide whether to continue to pay for it for those patients. UK agencies estimated the cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) at between £335,000 and £1,274,000 —well above the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence thresholds.[25]

The drug was not covered under the Ontario Drug Benefit plan until June 2014 when the Province of Ontario and the manufacturer negotiated for what "Ontario Health Minister Deb Matthews had called a “fair price” for taxpayers". The negotiations took 16 months and it was estimated that around 20 Ontarians required the drug at the time.[26]

The province of Alberta began covering the drug in July 2014, and in September the province of Saskatchewan became the third province to include it in its provincial drug plan.[27]

Government delays in agreeing to provide ivacaftor in national health plans led to patient group protests in Wales,[28][29] England,[30] and Australia.[31]

See also

- Ataluren, targeting premature stop codons

- Lumacaftor, targeting the F508del mutation

References

- ↑ Jones AM, Helm JM (October 2009). "Emerging treatments in cystic fibrosis". Drugs 69 (14): 1903–10. doi:10.2165/11318500-000000000-00000. PMID 19747007.

- ↑ McPhail GL, Clancy JP (April 2013). "Ivacaftor: the first therapy acting on the primary cause of cystic fibrosis". Drugs Today 49 (4): 253–60. doi:10.1358/dot.2013.49.4.1940984. PMID 23616952.

- ↑ "Phase 3 Study of VX-770 Shows Marked Improvement in Lung Function Among People with Cystic Fibrosis with G551D Mutation". Press Release. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "The Most Important New Drug Of 2012 - Forbes".

- ↑ "The $300,000 Drug - NYTimes.com".

- ↑ Eckford PD, Li C, Ramjeesingh M, Bear CE (October 2012). "Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor) opens the defective channel gate of mutant CFTR in a phosphorylation-dependent but ATP-independent manner". J. Biol. Chem. 287 (44): 36639–49. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.393637. PMID 22942289.

- ↑ Van Goor F, Hadida S, Grootenhuis PD, Burton B, Cao D, Neuberger T, Turnbull A, Singh A, Joubran J, Hazlewood A, Zhou J, McCartney J, Arumugam V, Decker C, Yang J, Young C, Olson ER, Wine JJ, Frizzell RA, Ashlock M, Negulescu P (November 2009). "Rescue of CF airway epithelial cell function in vitro by a CFTR potentiator, VX-770". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (44): 18825–30. doi:10.1073/pnas.0904709106. PMC 2773991. PMID 19846789.

- ↑ Sloane PA, Rowe SM (November 2010). "Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein repair as a therapeutic strategy in cystic fibrosis". Curr Opin Pulm Med 16 (6): 591–7. doi:10.1097/MCP.0b013e32833f1d00. PMID 20829696.

- ↑ "pi.vrtx.com" (PDF).

- ↑ "FAQs about the Cause, Diagnosis, Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis & More | CF Foundation".

- ↑ Bobadilla JL, Macek M, Fine JP, Farrell PM (June 2002). "Cystic fibrosis: a worldwide analysis of CFTR mutations--correlation with incidence data and application to screening". Hum. Mutat. 19 (6): 575–606. doi:10.1002/humu.10041. PMID 12007216.

- ↑ "pi.vrtx.com" (PDF).

- ↑ "pi.vrtx.com" (PDF).

- ↑ http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/sbd-smd/drug-med/sbd_smd_2012_kalydeco_155318-eng.php

- ↑ Accurso FJ, Rowe SM, Clancy JP, Boyle MP, Dunitz JM, Durie PR, Sagel SD, Hornick DB, Konstan MW, Donaldson SH, Moss RB, Pilewski JM, Rubenstein RC, Uluer AZ, Aitken ML, Freedman SD, Rose LM, Mayer-Hamblett N, Dong Q, Zha J, Stone AJ, Olson ER, Ordoñez CL, Campbell PW, Ashlock MA, Ramsey BW (November 2010). "Effect of VX-770 in persons with cystic fibrosis and the G551D-CFTR mutation". N. Engl. J. Med. 363 (21): 1991–2003. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909825. PMC 3148255. PMID 21083385.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "Kalydeco: Annex I: Summary of product characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency.

- ↑ "pi.vrtx.com" (PDF).

- ↑ "F.D.A. Approves New Cystic Fibrosis Drug". New York Times. January 31, 2012. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ↑ "Vertex Pharmaceuticals 10-Q, Quarter ending September 30, 2014". Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ↑ Brian P. O’Sullivan; David M. Orenstein; Carlos E. Milla (October 2, 2013). "Viewpoint: Pricing for Orphan Drugs: Will the Market Bear What Society Cannot?". JAMA. 310 (13): 1343–1344. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.278129.

- ↑ "Cystic Fibrosis: Charity and Industry Partner for Profit". MedPage Today. May 19, 2013. Retrieved 2015-02-10.

- ↑ "CF Foundation Cashes Out on Kalydeco in $3.3B Sale to Royalty Pharma | Xconomy".

- ↑ "CF Foundation Royalty Sale Will Be Transformational for People with CF".

- ↑ "FDA Approves KALYDECO™ (ivacaftor), the First Medicine to Treat the Underlying Cause of Cystic Fibrosis" (Press release). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Vertex Pharmaceuticals. 2012-01-31. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

- ↑ Deborah Cohen; James Raftery (12 February 2014). "Orphan Drugs: Paying twice: questions over high cost of cystic fibrosis drug developed with charitable funding". BMJ 348: g1445. doi:10.1136/bmj.g1445.

- ↑ Ferguson, Rob (June 20, 2014). "OHIP to cover cystic fibrosis drug Kalydeco". The Toronto Star. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Saskatchewan to cover $300K cystic fibrosis drug Kalydeco". CBC News. 2014-08-28. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- ↑ "Plea for Kalydeco drug to be introduced | Wales - ITV News".

- ↑ "BBC News - Cystic fibrosis: New drug Kalydeco refused for Welsh NHS".

- ↑ "Protests at Birmingham Hospital as cystic fibrosis sufferer is denied life-saving drug - Birmingham Mail".

- ↑ "Kalydeco breakthrough: Plea for life-saving medicine proves a winner | Manning River Times".

External links

- FAQs About VX-770 from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||