Iva Toguri D'Aquino

| Iva Toguri D'Aquino 戸栗郁子 アイバ | |

|---|---|

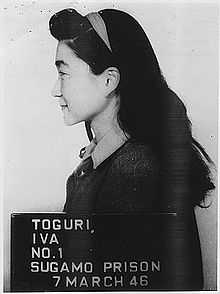

Iva Toguri mug shot, Sugamo Prison - March 7, 1946 | |

| Born |

Iva Toguri July 4, 1916 Los Angeles, California |

| Died |

September 26, 2006 (aged 90) Chicago, Illinois |

Cause of death | Natural causes |

Resting place | Montrose Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names |

Tokyo Rose Orphan Anne |

| Education | University of California, Los Angeles |

| Occupation | typist and broadcaster, merchant |

| Employer | Japanese central government's news agency and Radio Tokyo |

| Known for | Announcing propaganda on Japanese radio during World War II |

| Spouse(s) |

Felipe D'Aquino (m.1945-1980; divorced) |

| Parent(s) | Jun and Fumi Toguri |

Iva Ikuko Toguri D'Aquino (July 4, 1916 – September 26, 2006) was an American who participated in English-language propaganda broadcast transmitted by Radio Tokyo to Allied soldiers in the South Pacific during World War II. Although on The Zero Hour radio show, Toguri called herself "Orphan Ann," she quickly became identified with the moniker "Tokyo Rose", a name that was coined by Allied soldiers and that predated her broadcasts. After the Japanese defeat, Toguri was detained for a year by the United States military before being released for lack of evidence. Department of Justice officials agreed that her broadcasts were "innocuous". But when Toguri tried to return to the US, a popular uproar ensued, prompting the Federal Bureau of Investigation to renew its investigation of Toguri's wartime activities. She was subsequently charged by the United States Attorney's Office with eight counts of treason. Her 1949 trial resulted in a conviction on one count, making her the seventh American to be convicted on that charge, for which she spent more than six years out of a ten-year sentence in prison. Belatedly, however, after investigative journalists found that key witnesses claimed they were forced to lie during testimony, Toguri was pardoned by U.S. President Gerald Ford in 1977.[1]

Early life

Iva Ikuko Toguri (戸栗郁子 アイバ Toguri Ikuko Iba) was born in Los Angeles, a daughter of Japanese immigrants. Her father, Jun Toguri, had come to the U.S. in 1899, and her mother, Fumi, in 1913. Iva was a Girl Scout as a child, and was raised as a Methodist. She attended grammar schools in Mexico and San Diego before returning with her family to Los Angeles. There she finished grammar school, attended high school, and graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles, with a degree in zoology.[2] She then went to work in her parents' shop. As a registered Republican, she voted for Wendell Wilkie in the 1940 presidential election.

On July 5, 1941, Toguri sailed for Japan from the San Pedro, Los Angeles area, to visit an ailing relative and to possibly study medicine. The U.S. State Department issued her a Certificate of Identification; she did not have a passport. In September, Toguri applied to the U.S. Vice Consul in Japan for a passport, stating she wished to return to her home in the U.S. Her request was forwarded to the State Department, but the answer had not returned by the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7, 1941) and she was stranded in Japan.

Zero Hour

With the beginning of American involvement in the Pacific War, Toguri, like a number of other Americans in Japanese territory, was pressured by the Japanese central government under Hideki Tojo to renounce her United States citizenship. She refused to do so. Toguri was subsequently declared an enemy alien and was refused a war ration card.[3] "A tiger does not change its stripes" is a quote attributed to her.[3] To support herself, she found work as a typist at a Japanese news agency and eventually worked in a similar capacity for Radio Tokyo.

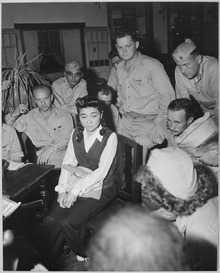

In November 1943, Allied prisoners of war forced to broadcast propaganda selected her to host portions of the one-hour radio show The Zero Hour. Her producer was an Australian Army officer, Major Charles Cousens, who had pre-war broadcast experience and had been captured at the fall of Singapore. Cousens had been tortured and coerced to work on radio broadcasts,[3] as had his assistants, U.S. Army Captain Wallace Ince and Philippine Army Lieutenant Normando Ildefonso "Norman" Reyes. Toguri had previously risked her life smuggling food into the nearby prisoner of war (POW) camp where Cousens and Ince were held, gaining the inmates' trust.[3] After she refused to broadcast anti-American propaganda, Toguri was assured by Major Cousens and Captain Ince that they would not write scripts having her say anything against the United States.[3] True to their word, no such propaganda was found in her broadcasts.[3] Toguri hosted a total of 340 broadcasts of The Zero Hour.[3]

Under the stage names "Ann" (for "Announcer") and later "Orphan Annie"[3] and possibly "Your Favorite Enemy, Annie", reportedly in reference to the comic strip character Little Orphan Annie, Toguri performed in comedy sketches and introduced recorded music, but never participated in any actual newscasts, with on-air speaking time of generally about 20 minutes. Though earning only 150 yen, or about $7, per month, she used some of her earnings to feed POWs,[4] smuggling food in as she did before.

Toguri aimed most of her comments toward her fellow Americans ("my fellow orphans"), using American slang and playing American music. She routinely referred to American and allied troops in the Pacific theater as "boneheads". In one of the few surviving recordings of her show, she refers to herself as "your 'Number One' enemy."

At no time did Toguri call herself "Tokyo Rose" during the war, and in fact there was no evidence that any other broadcaster had done so. The name was a catch-all used by Allied forces for all of the women who were heard on Japanese propaganda radio.

She married Felipe D'Aquino (last name sometimes given only as Aquino), a Portuguese citizen of Japanese-Portuguese descent, on April 19, 1945. At the same time, Toguri formally became a Catholic, a faith she would keep through her prison years. The marriage was registered with the Portuguese Consulate in Tokyo, with Toguri declining to take her husband's citizenship.

Postwar arrest and trial

Arrest

After Japan's unconditional surrender (August 15, 1945), reporters Harry T. Brundidge of Cosmopolitan Magazine and Clark Lee of Hearst's International News Service (INS) offered $2,000 (the equivalent of a year's wages in Occupied Japan) for an exclusive interview with "Tokyo Rose".[5]

In need of money, and still trying to get home, Iva stepped forward to claim the money, but instead found herself arrested, on September 5, 1945, in Yokohama. Brundidge not only used her arrest and subsequent public press conference as an excuse to renege on the "exclusive interview" deal and nullify any payment, but also tried to sell his transcript of the interview as Iva's "confession". She was released after a year in jail when neither the FBI nor General Douglas MacArthur's staff found any evidence she had aided the Japanese Axis forces.[4] Furthermore, the American and Australian prisoners of war who wrote her scripts assured her (and the Allied headquarters) that she had committed no wrongdoing.[6]

The case history at the FBI's website states, "The FBI's investigation of Aquino's activities had covered a period of some five years. During the course of that investigation, the FBI had interviewed hundreds of former members of the U.S. Armed Forces who had served in the South Pacific during World War II, unearthed forgotten Japanese documents, and turned up recordings of Aquino's broadcasts". Investigating with the U.S. Army's Counterintelligence Corps, they "conducted an extensive investigation to determine whether Aquino had committed crimes against the U.S. By the following October, authorities decided that the evidence then known did not merit prosecution, and she was released."[7]

Upon her request to return to the United States to have her child born on American soil,[3] the influential gossip columnist and radio host Walter Winchell lobbied against her. Her baby was born in Japan, but died shortly after.[3] Following her child's death, D'Aquino was rearrested by the U.S. military authorities and transported to San Francisco, on September 25, 1948, where she was charged by federal prosecutors with the crime of treason for "adhering to, and giving aid and comfort to, the Imperial Government of Japan during World War II".

Treason trial

Her trial on eight "overt acts" of treason began on July 5, 1949, at the Federal District Court in San Francisco. During what was at the time the costliest and longest trial in American history,[2] totaling more than half a million dollars ($4.96 million in today's dollars),[8] the prosecution presented 46 witnesses, including two of Toguri's former supervisors at Radio Tokyo, and soldiers who testified they could not distinguish between what they had heard on radio broadcasts and what they had heard by way of rumor. Although boxes of tapes were brought by prosecutors to the courthouse and rested near the prosecution table, none were entered into evidence and played for the jury.

Toguri was defended by a team of attorneys, led by Wayne Mortimer Collins, a prominent advocate of Japanese-American rights. Collins enlisted the help of Theodore Tamba, who became one of Toguri's closest friends, a relationship which continued until his death in the 1970s.

During the trial, the former supervisor at Radio Tokyo testified that:

| “ | I said to Toguri I had a release from the Imperial General Headquarters giving out results of American ship losses in one of the Leyte Gulf battles, and I asked that she allude to this announcement, make reference to the losses of American ships in her part of the broadcast, and she said she would do so. | ” |

On September 29, 1949, the jury found Toguri guilty on a sole count, Count VI, which stated, "That on a day during October, 1944, the exact date being to the Grand Jurors unknown, said defendant, at Tokyo, Japan, in a broadcasting studio of The Broadcasting Corporation of Japan, did speak into a microphone concerning the loss of ships." She was fined $10,000 and given a 10-year prison sentence, with Toguri's attorney Collins lambasting the verdict as "Guilty without evidence".[3] She was sent to the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia. She was paroled after serving six years and two months, and released January 28, 1956. She moved to Chicago, Illinois. The FBI's case history notes, "Neither Brundidge nor the [suborned] witness [Hiromu Yagi] testified at trial because of the taint of perjury. Nor was Brundidge prosecuted for subornation of perjury."

Presidential pardon

In 1976, an investigation by Chicago Tribune reporter Ron Yates discovered that Kenkichi Oki and George Mitsushio, who had given the most damaging testimony at Toguri's trial, had perjured themselves. They stated that FBI and U.S. occupation police had coached them for over two months about what they were to say on the stand, and had been threatened with treason trials themselves if they didn't cooperate.[9] This was followed up by a Morley Safer report on the television news program 60 Minutes.[10]

Owing to these revelations, U.S. President Gerald Ford granted a full and unconditional pardon to Iva Toguri D'Aquino on January 19, 1977, his last full day in office. The decision was supported by a unanimous vote in both houses of the California State Legislature, the national Japanese American Citizens League, and S. I. Hayakawa, then a United States Senator from California. The pardon restored her U.S. citizenship, which had been abrogated as a result of her conviction.[11]

Later life

On January 15, 2006, the World War II Veterans Committee (sponsors of the Memorial Day Parade in Washington D.C. and the National World War II Memorial, the newest monument on the National Mall), citing "her indomitable spirit, love of country, and the example of courage she has given her fellow Americans", awarded Toguri its annual Edward J. Herlihy Citizenship Award.[12] According to one biographer, Toguri found it the most memorable day of her life.[9]

On September 26, 2006, at the age of 90, Toguri died in a Chicago hospital of natural causes.[13][14]

Legacy

According to Richard Goldstein, writing her obituary for The New York Times, "The broadcasts did nothing to dim American morale. The servicemen enjoyed the recordings of American popular music, and the United States Navy bestowed a satirical citation on Tokyo Rose at war’s end for her entertainment value."[15]

Media depictions and references

Iva Toguri has been the subject of two movies and five documentaries:

- 1946: Tokyo Rose, film; directed by Lew Landers. Lotus Long played a heavily fictionalized "Tokyo Rose", described on the film's posters as a "seductive jap traitress";[16] Byron Barr played the G.I. protagonist, who kidnaps the Japanese announcer. Blake Edwards appeared in a supporting part. The film espoused the general public's view of "Tokyo Rose" at the time of Toguri's arrest. While the film's character was not referred to by her actual name, Long was made to look like Toguri.[17]

- 1969: The Story of "Tokyo Rose", CBS-TV and WGN radio documentary written and produced by Bill Kurtis.

- 1976: Tokyo Rose, CBS-TV documentary segment on 60 Minutes by Morley Safer, produced by Imrel Harvath.

- 1995: U.S.A. vs. "Tokyo Rose", self-produced documentary by Antonio A. Montanari Jr., distributed by Cinema Guild.

- 1995: Tokyo Rose: Victim of Propaganda, A&E Biography documentary, hosted by Peter Graves, available on VHS (AAE-14023).

- 1999: Tokyo Rose: Victim of Propaganda, History International, Produced by Scott Paddor, Editor Steve Pomerantz, A&E Director Bill Harris

- In 2004, actor George Takei announced he was working on a film titled Tokyo Rose, American Patriot, about Toguri's activities during the war.[18]

- 2008-9: Tokyo Rose, film; in development with Darkwoods Productions, the only entity granted life story rights by Iva Toguri, Frank Darabont to direct. Christopher Hampton, is the screenwriter for Tokyo Rose.

- On 20 July 2009, History Detectives (Season 7, Episode 705) aired a 20-minute segment entitled Tokyo Rose Recording researched by Gwendolyn Wright tracing the recording of live coverage of Iva Toguri's 25 September 1948 arrival in San Francisco under military escort for trial. The investigation of the origins of this recording documents the involvement of the self-serving reporter Harry T. Brundidge and his part in the fraudulent case against her.

The first registered rock group using the name Tokyo Rose was formed in the summer of 1980. They are most known for their video which tells the story of the war time Tokyo Rose. Tokyo Rose is also the name of an emo/pop band hailing from New Jersey. Tokyo Rose is a 1989 album by Van Dyke Parks. The album attempts to reflect an intersection between Japanese and American cultures, a common concern during the 1980s. The Canadian group Idle Eyes had a hit in 1985 in Canada with the song "Tokyo Rose" from their self-titled debut from WEA Music Canada. Vigilantes of Love scored a hit with "Tokyo Rose"[19] from their 1997 album, Slow Dark Train.

See also

- Axis Sally (disambiguation)

- Harold Harby, Los Angeles City Council member, 1939–42, 1943–57, urged the council to keep Tokyo Rose out of America

- Philippe Henriot

- Lord Haw Haw

- List of people pardoned or granted clemency by a United States president

- Ezra Pound

- Stuttgart traitor

- Tokyo Rose

- P. G. Wodehouse - English writer used in German radio broadcasts during World War II

References

- ↑ Masayo Duus, Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific, Kodansha International, 1979; Ann Elizabeth Pfau, Miss Yourlovin: GIs, Gender, and Domesticity during World War II, Columbia University Press, 2008, chapter 5, http://www.gutenberg-e.org/pfau/chapter5.html

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Edward J. Herlihy 2005 Citizenship Award Recipient Iva Toguri". American Veterans Center. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 From the 1995 A&E program "Tokyo Rose: Victim of Propaganda"

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Siemaszko, Corky. New York Daily News (July 4, 2006): "Still not Tokyo Rose: Long free, at 90, she's imprisoned by a myth"

- ↑ Clark Lee, One last look around, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1947, p. 84 ff.

- ↑ "Iva Toguri D'Aquino Dies at 90" on National Public Radio

- ↑ Rex B. Gunn (1977). They Called Her Tokyo Rose. Self-published. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0979698705.

- ↑ Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2014. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Death ends the myth of Tokyo Rose". BBC. September 28, 2006.

- ↑ Reported by Morley Safer (June 24, 1976). "Tokyo Rose," 60 Minutes. (Television). New York: CBS.

- ↑ Bernstein, Adam (September 28, 2006). "Iva Toguri, 90, branded as WWII 'Tokyo Rose'". Boston Globe. Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- ↑ Setting the Record Straight

- ↑ "Woman tried as ‘Tokyo Rose’ dies in Chicago". Reuters. September 27, 2006.

- ↑ "Obituary of Iva Toguri". London: The Times. September 28, 2006.

- ↑ Goldstein, Richard (September 27, 2006). "D’Aquino, Convicted as Tokyo Rose, Dies at 90". The New York Times.

- ↑ Popartmachine.com

- ↑ Earthstation1.com

- ↑ Chun, Gary C.W. "Star Trek 's Lt. Sulu plans to make his film, Tokyo Rose: American Patriot, in Hawaii", StarBulletin.com, April 12, 2004.

- ↑ Music: Parting Shot

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iva Ikuko Toguri D'Aquino. |

- EarthStation1: Orphan Ann Broadcast Audio

- Mug shots of D'Aquino, thesmokinggun.com

- The Legend of Tokyo Rose book chapter by Ann Ellizabeth Pfau