Italic peoples

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins

|

|

Archaeology |

|

Peoples and societies

|

|

Religion and mythology |

The Italic peoples are an Indo-European ethnic-linguistic group primarly living in Southern Europe, Western Europe and the Americas who speak the Indo-European Italic languages, and share, to varying degrees, certain cultural traits and historical backgrounds.[1] Through the expansion of Ancient Rome, the Italic peoples spread over a large area in Europe, North Africa and West Asia. During the Age of Exploration, through the Spanish and Portuguese Empire, they achieved further influence in Central and Southern America, which spread the Italic languages and Roman Catholic Christianity into the Western Hemisphere.[2]

Etymology

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins

|

|

Archaeology |

|

Peoples and societies

|

|

Religion and mythology |

According to one of the more common explanations, the term Italia, from Latin: Italia,[3] was borrowed through Greek from the Oscan Víteliú, meaning "land of young cattle" (cf. Lat vitulus "calf", Umb vitlo "calf").[4] The bull was a symbol of the southern Italian tribes and was often depicted goring the Roman wolf as a defiant symbol of free Italy during the Social War. Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus states this account together with the legend that Italy was named after Italus,[5] mentioned also by Aristotle[6] and Thucydides.[7]

The name Italia originally applied only to a part of what is now Southern Italy – according to Antiochus of Syracuse, the southern portion of the Bruttium peninsula (modern Calabria: province of Reggio, and part of the provinces of Catanzaro and Vibo Valentia). But by his time Oenotria and Italy had become synonymous, and the name also applied to most of Lucania as well. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name "Italia" to a larger region, but it was during the reign of Emperor Augustus (end of the first century BC) that the term was expanded to cover the entire peninsula until the Alps.[8]

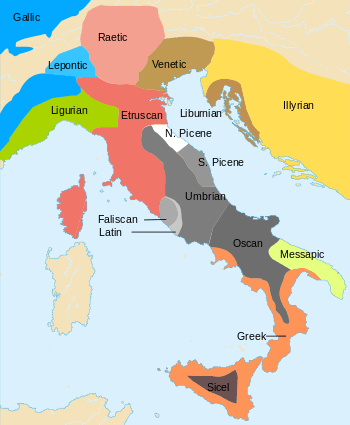

Classification

The Italics were all the people who spoke an idiom belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages and had settled in the Italian peninsula. The first Italic tribes, the Latino-Falisci (or "Latino-Veneti", if the membership of the ancient Veneti is also accepted), entered Italy across the eastern Alpine passes into the plain of the Po River about 1200 BC. Later they crossed the Apennine Mountains and eventually occupied the region of Latium, which included the area of Rome. Before 1000 BC, the Osco-Umbrians followed, which later divided into various groups and gradually moved to central and southern Italy.

The Italics are therefore the set of all Indo-Europeans present exclusively in Italy in antiquity, and not Indo-European people that were present also in other areas of Europe, such as the Cisalpine Gauls (a Continental Celtic people) or the Messapians (related to the Illyrians). In improper sense, the term is sometimes used, especially in the non-specialized literature, to refer to all pre-Roman people of Italy, including therefore (definitely or supposedly) not of Indo-European lineages, such as the Etruscans, the Raetians and the Elymians.

History

Copper Age

Remains of the later prehistoric age have been found in Liguria and Lombardy (stone carvings in Val Camonica). The most famous is perhaps that of Ötzi the Iceman, the mummy of a mountain hunter found in the Similaun glacier in South Tyrol, dating to c. 3300 BC. During the Copper Age, at the same time as metalworking appeared, Indo-European people migrated to Italy. Approximatively four waves of population from north to the Alps have been hypothesized on the basis of archaeological evidence.[9] The Remedello culture is associated by some with the first identified wave of Proto-Indo-Europeans who entered Italy and took over the Po Valley.[10]

Early and Middle Bronze Age

From the late 3rd to the early 2nd millennium BC, tribes coming both from the north and from Franco-Iberia brought the Beaker culture[11] and the use of bronze smithing, in the Po Valley, in Tuscany and on the coasts of Sardinia and Sicily.

The first Italic tribes to enter the Italian peninsula, moved across the eastern Alpine passes into the plain of the Po River about 1800 BC. Later they crossed the Apennines and eventually occupied the region of Latium, which included Rome. Before 1000 BC related tribes followed, which later divided into various groups and gradually moved to central and southern Italy.[2]

In the mid-2nd millennium BC, the Terramare culture[12] developed in the Po Valley. The Terramare culture takes its name from the black earth (terra marna) residue of settlement mounds, which have long served the fertilizing needs of local farmers. They were still hunters, but had domesticated animals; they were fairly skillful metallurgists, casting bronze in moulds of stone and clay, and they were also agriculturists, cultivating beans, the vine, wheat and flax. The Latino-Faliscan people have been associated with this culture, especially by the archaeologist Luigi Pigorini.

Late Bronze Age

From the late 2nd millennium to the early 1st millennium BC, the Late Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture, related to the Central European Urnfield culture, dominated the peninsula and replaced the preceding Apennine culture. The Proto-Villanovans practiced cremation and buried the ashes of their dead in pottery urns of a distinctive double-cone shape. Generally speaking, Proto-Villanovan settlements have been found in almost the whole Italian peninsula from Veneto to eastern Sicily, although they were most numerous in the northern-central part of Italy. The most important settlements excavated are those of Frattesina in Veneto region, Bismantova in Emilia-Romagna and near the Monti della Tolfa, north of Rome. The Osco-Umbrians, the Veneti, and possibly the Latino-Faliscans too, have been associated with this culture.

In the 13th century BC, Proto-Celts (probably the ancestors of the Lepontii people), coming from the area of modern-day Switzerland, eastern France and south-western Germany (RSFO Urnfield group), entered Northern Italy (Lombardy and eastern Piedmont), starting the Canegrate culture, who not long time after, merging with the indigenous Ligurians, produced the mixed Golasecca culture.

Iron Age

In the early Iron Age, the relatively homogeneous Proto-Villanovan culture shows a process of fragmentation. In Tuscany and in part of Emilia-Romagna, the Proto-Villanovan culture was followed by the Villanovan culture, often associated with the non-Indo-European Etruscans. In the south of the Tiber (Latium Vetus), the Latial culture of the Latins emerges, while in the north-east of the peninsula the Este culture of the Veneti appeared. Roughly in the same period, from their core area in central Italy (modern-day Umbria and Sabina region), the Osco-Umbrians began to emigrate in various waves (Ver sacrum) in southern Latium, Marche and the whole southern half of the peninsula, replacing the previous tribes, such as the Opici and the Oenotrians, that inhabited those lands before them.

Ancient tribes

- Latino-Faliscans including:

- Osco-Umbrians or Sabellians including:

- Umbrians (ethnicity sabellians, language umbrian)

- Oscans (ethnicity sabellians, language oscan)

- Samnitics (ethnicity sabellians, language oscan)

- Other Sabellians (ethnicity sabellians, language oscan)

Language

The Italic subfamily is a member of the Indo-European language family. It includes the Romance languages derived from Latin (Catalan, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Romanian, Occitan, etc.), and a number of extinct languages of the Italian Peninsula, including Umbrian, Oscan, Faliscan, and South Picene.

Italic includes the Latin subgroup (Latin and the Romance languages) as well as the ancient Italic languages (Faliscan, Osco-Umbrian and two unclassified Italic languages, Aequian and Vestinian). Venetic (the language of the ancient Veneti), as revealed by its inscriptions, was also closely related to the Italic languages and is sometimes classified as Italic. However, since it also shares similarities with other Western Indo-European branches (particularly Germanic), some linguists prefer to consider it an independent Indo-European language.

In the extreme view, Italic did not exist, but the different groups descended directly from Indo-European and converged because of geographic contiguity. This view stems in part from the difficulty in identifying a common Italic homeland in prehistory.[15]

In the intermediate view, the Italic languages are one of the ten or eleven major subgroups of the Indo-European language family and might therefore have had an ancestor, common Italic or proto-Italic, from which its daughter languages descend. Moreover, there are similarities between major groups, although how these similarities are to be interpreted is one of the major debatable issues in the historical linguistics of Indo-European. The linguist Calvert Watkins went so far as to suggest, among ten major groups, a four-way division of East, West, North and South Indo-European. These he considered "dialectical divisions within Proto-Indo-European which go back to a period long before the speakers arrived in their historical areas of attestation."[16] This is not to be considered a nodular grouping; in other words, there was not necessarily any common west Indo-European serving as a node from which the subgroups branched, but rather a hypothesized similarity between the dialects of Proto-Indo-European which developed into the recognized families. The West Indo-European dialects are Celtic, Italic and Tocharian. By the time of any written language, Tocharian was geographically remote from the other two.

Branches

The Italic family has two known branches:

- Latino-Faliscan, including:

- Faliscan, which was spoken in the area around Falerii Veteres (modern Civita Castellana) north of the city of Rome and possibly Sardinia

- Latin, which was spoken in west-central Italy. The Roman conquests eventually spread it throughout the peninsula and beyond in the Roman Empire.

- Romance languages, the descendants of Latin

- Osco-Umbrian or Sabellian including:

- Oscan, which was spoken in the south-central region of the Italian Peninsula

- Umbrian (not to be confused with the modern Umbrian dialect of Italian), which was spoken in the north-central region

- Volscian

- Marsian, the language of the Marsi

- South Picene, in east-central Italy

- Sabine in Lazio and the central Apennines

See also

References

- ↑ Waldman 2006, p. 452-453.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "history of Europe : Romans". Encylopedia Britannica online. Encyclopedia Briannica Inc. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- ↑ OLD, p. 974: "first syll. naturally short (cf. Quint.Inst.1.5.18), and so scanned in Lucil.825, but in dactylic verse lengthened metri gratia."

- ↑ Mallory 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Roman Antiquities, 1.35, on LacusCurtius

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics, 7.1329b, on Perseus

- ↑ Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War, 6.2.4, on Perseus

- ↑ Pallottino 1991, p. 50.

- ↑ J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams, Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Italic languages pg. 315-319

- ↑ Remedello culture map

- ↑ p144, Richard Bradley The prehistory of Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-521-84811-3

- ↑ Pearce, Mark (December 1, 1998). "New research on the terramare of northern Italy". Antiquity.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Strabo V, 250.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 14.10 Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, III, 98.

- ↑ Silvestri 1998, pp. 322–323.

- ↑ Watkins 1998, pp. 31–33

Bibliography

- Devoto, Giacomo; Buti, Gianna G. (1974). Preistoria e storia delle regioni d'Italia. Florence: Sansoni.

- Devoto, Giacomo (1951). Gli antichi Italici. Florence: Vallechi.

- Moscati, Sabatino (1998). Così nacque l'Italia: profili di popoli riscoperti. Turin: Società Editrice Internazionale.

- Pigorini, Luigi (1910). Gli abitanti primitivi dell'Italia. Rome: Bertero.

- Silvestri, Domenico (1998), "The Italic Languages", in Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo, The Indo-European languages, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 322–344.

- Villar, Francisco (1997). Gli Indoeuropei e le origini dell'Europa. Bologna: Il Mulino. ISBN 88-15-05708-0.

- Watkins, Calvert (1998), "Proto-Indo-European: Comparison and Reconstruction", in Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo, The Indo-European languages, Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 25–73.