Italian general election, 1867

_crowned.svg.png)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Composition of the Parliament |

|

Bettino Ricasoli resigned as Prime Minister of Italy on 10 April 1867, due to a recalcitrant Italian Chamber. The chamber disagreed with his agreements with the Vatican regarding the repatriation of certain religious properties. Subsequent to his resignation, general elections were held in Italy on 10 March 1867; with the second round of voting on 17 March 1867.[1] These snap elections resulted in Urbano Rattazzi being elected once again to office.[2]

Due to the restrictive Italian electoral laws of the time, only 504,265 Italian men, out of a total population of around 26 million, were entitled to vote. The voters were largely aristocrats, rentiers, and capitalists, who tended to hold moderate political views, including loyalty to the crown and low government spending.[3]

The race

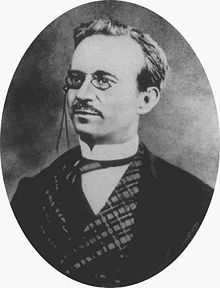

The opposition to Ricasoli was mainly organized by former Prime Minister Rattazzi, a moderate member of the Historical Left, who had entered into a coalition with the Historical Right in Piedmont fifteen years earlier. Even though Italian elections were officially non-partisan, the political conflict was so evident that the election became a match between these two political heavyweights.[4]

The 1867 election was a great defeat for Ricasoli, who thereafter retired to private life. However, while Ricasoli lost, Rattazzi did not receive a clear mandate, especially during the second part of the traditional two-round system. Many Independent candidates, who were ready to support any government that would support their local interests, were lukewarm supporters at best. Ultimately, Rattazzi was charged by the king to form a new government, but the fickle leftist faction abandoned him, forcing Rattazzi to form a new coalition.[5] This was typical of Italian politics of the day, which were officially non-partisan with no structured parties. Voters instead were influenced more by localism and corruption, rather than loyalty to any leader or party.[6]

Rattazzi tried to form a centrist government consisting of his centre-left moderate faction, some Independents, and the Historical Right. These groups agreed to the coalition in order to later regain control. However, despite his efforts, Rattazzi's victory was ephemeral, similar to his first term as Prime Minister in 1862: barely six months later he was unable to stop an armed attack by a national hero, Giuseppe Garibaldi, upon the Papal State. The King, seeing that Rattazzi was ineffective, quickly forced his resignation. Senator Federico Luigi Menabrea then took over as Prime Minister, with the Historical Right regaining full control of the government.[7]

Parties and leaders

Results

| Affiliation |

Votes |

First round |

% of seats |

Votes |

Second round |

% of seats |

Total |

|---|

|

Historical Right | | 56 | 26.9 | | 95 | 39.3 | 151 |

|

Historical Left | | 121 | 58.2 | | 104 | 43.0 | 225 |

|

Independents | | 31 | 14.9 | | 43 | 17.8 | 74 |

| Invalid seats[8] | | – | – | | – | – | 43 |

| Invalid/blank votes | | | | | | | |

| Total | 276,523 | 208 | 100 | n/a | 242 | 100 | 493 |

| Registered voters/turnout | 504,265 | 54.8 | – | n/a | n/a | – | |

| Source: "La Stampa", Tuesday, 19 March 1867. |

References

- ↑ Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1047 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- ↑ La Stampa, Sunday, 10 March 1867.

- ↑ Nohlen & Stöver, p1028

- ↑ La Stampa, Saturday, 23 March 1867.

- ↑ La Stampa, Friday, 12 April 1867.

- ↑ La Stampa, Saturday, 13 April 1867.

- ↑ "Federico Menabrea" in Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ The electoral law did not limit the number of constituencies where a candidate could stand, so many political leaders run and won in two or more constituencies, which consequently needed by-elections to fill their seats.