Isthmus of Panama

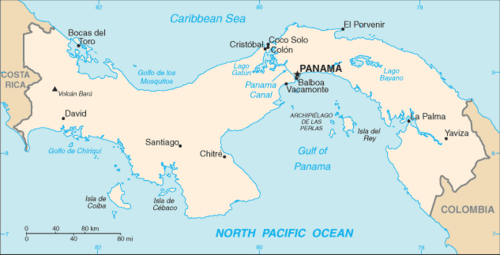

The Isthmus of Panama, also historically known as the Isthmus of Darien, is the narrow strip of land that lies between the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, linking North and South America. It contains the country of Panama and the Panama Canal. Like many isthmuses, it is a location of great strategic value.

The isthmus was arguably formed 12 to 15 million years ago.[1] This major geological event separated the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans and caused the creation of the Gulf Stream.

History

Vasco Núñez de Balboa heard of the South Sea from natives while sailing along the Caribbean coast. On 25 September 1513 he saw the Pacific. In 1519 the town of Panamá was founded near a small indigenous settlement on the Pacific coast. After the discovery of Peru, it developed into an important port of trade and became an administrative centre. In 1671 the Welsh pirate Henry Morgan crossed the Isthmus of Panamá from the Caribbean side and destroyed the city. The town was relocated some kilometers to the west at a small peninsula. The ruins of the old town, Panamá Viejo, are preserved and were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

Silver and gold from the viceroyalty of Peru were transported overland across the isthmus to Porto Bello, where Spanish treasure fleets shipped them to Seville and Cádiz from 1707.

Lionel Wafer spent four years between 1680 and 1684 among the Cuna Indians.

Scotland tried to establish a settlement in 1698 through the Darien scheme.

The California Gold Rush, starting in 1849, brought a large increase in the transportation of people from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Steamships brought gold seekers from eastern US ports who trekked across the isthmus by foot, horse, and later rail. On the Pacific side, they boarded Pacific Mail Steamship Company vessels headed for San Francisco.

Ferdinand de Lesseps, the man behind the Suez Canal, started a Panama Canal Company in 1880 that went bankrupt in 1889 in a scandal.

In 1902–4, the United States forced Colombia to grant independence to the department of the isthmus, bought the remaining assets of the Panama Canal Company, and finished the canal in 1914.

Geology

A significant body of water (referred to as the Central American Seaway) once separated the continents of North and South America, allowing the waters of the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans to mix freely. Beneath the surface, two plates of the Earth's crust were slowly colliding, forcing the Cocos Plate to slide under the Caribbean Plate. The pressure and heat caused by this collision led to the formation of underwater volcanoes, some of which grew large enough to form islands as early as 15 million years ago. Meanwhile, movement of the two tectonic plates was also pushing up the sea floor, eventually forcing some areas above sea level.

Over time, massive amounts of sediment (sand, soil, and mud) from North and South America filled the gaps between the newly forming islands. Over millions of years, the sediment deposits added to the islands until the gaps were completely filled. By no later than 4.5 million years ago, an isthmus had formed between North and South America. However, in April 2015, an article in Science Magazine stated that zircon crystals in middle Miocene bedrock from northern Colombia indicated that by 10 million years ago, it is likely that instead of islands, a full isthmus between the North and South American continents had already likely formed where the Central American Seaway had been previously.[2]

Scientists believe the formation of the Isthmus of Panama is one of the most important geologic events in the last 60 million years. Though only a small sliver of land relative to the sizes of continents, the Isthmus of Panama had an enormous impact on the earth's climate and environment. By shutting down the flow of water between the two oceans, the land bridge rerouted ocean currents in both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Atlantic currents were forced northward and eventually settled into a new current pattern that we now call the Gulf Stream. With warm Caribbean waters flowing toward the northeast Atlantic, the climate of northwestern Europe and eastern North America grew warmer. (However, it is actually the directly affected atmospheric circulation rather than the Gulf Stream that results in the pronounced temperature differential between Europe and eastern North America - Seager, 2006). Evaporation in the tropical Atlantic and Caribbean caused freshwater vapor to enter the atmosphere, while leaving behind salty water. The trade winds (blowing east to west) carried the water vapor and deposited it in the Pacific by precipitation. As a result, the Atlantic became saltier than the Pacific.[3] Each of these changes helped establish the global ocean circulation pattern in place today. In short, the Isthmus of Panama directly and indirectly influenced ocean and atmospheric circulation patterns, which regulated patterns of rainfall, which in turn sculpted landscapes.[4]

Evidence also suggests that the creation of this land mass and the subsequent warm, wet weather over northern Europe resulted in the formation of a large Arctic ice cap and contributed to the current ice age. That warm currents can lead to glacier formation may seem counterintuitive, but heated air flowing over the warm Gulf Stream can hold more moisture. The result is increased precipitation that contributes to snow pack.

The formation of the Isthmus of Panama also played a major role in biodiversity on the planet. The bridge made it easier for animals and plants to migrate between the two continents. This event is known in paleontology as the Great American Interchange. For instance, in North America today, the opossum, armadillo, and porcupine all trace back to ancestors that came across the land bridge from South America. Likewise, ancestors of bears, cats, dogs, horses, llamas, and raccoons all made the trek south across the isthmus. (Many of the South American mammals went extinct. It seems that the North American mammals were more accustomed to competition and better suited to the cooling climate.)

Biosphere

As the connecting bridge between two vast land masses, the Panamanian biosphere is filled with overlapping fauna and flora from both North and South America. There are, for example, over 978[5] species of birds in the isthmus area. The tropical climate also encourages a myriad of large and brightly coloured species: insects, snakes, birds, fish, and reptiles. Divided along its length by a mountain range, the isthmus's weather is generally wet on the Atlantic (Caribbean) side but has a clearer division into wet and dry seasons on the Pacific side.

References

- ↑ Land Bridge Linking Americas Rose Earlier Than Thought, LiveScience.com

- ↑ "North and South America Came Together Much Earlier Than Thought: Study". nbcnews.com. NBC News through Reuters. April 9, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ Gerald H. Haug; Lloyd D. Keigwin. "How the Isthmus of Panama Put Ice in the Arctic: Drifting continents open and close gateways between oceans and shift Earth's climate". Oceanus. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ "Panama: Isthmus that Changed the World". NASA Earth Observatory. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- ↑ The Birds of Panama A Field Guide by George R. Angehr and Robert Dean

- Panama: Isthmus that Changed the World. NASA Earth Observatory. (2003) The original text, where the geology section of this article has been stolen from.

- A New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America (1695), by Lionel Wafer. Excerpt from the 1729 Knapton edition

- Mellander, Gustavo A.(1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Daville,Ill.:Interstate Publishers. OCLC 138568.

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1-56328-155-4. OCLC 42970390.

Seager, R. (2006) 'The Source of Europe’s Mild Climate.', American Scientist, 94(4), pp. 334.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isthmus of Panama. |