Iran

| Islamic Republic of Iran |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: استقلال، آزادی، جمهوری اسلامی "Esteqlāl, Āzādi, Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi" "Independence, freedom, the Islamic Republic" (de facto)[1] |

||||||

| Anthem: مهر خاوران Mehr-e Xāvarān The Eastern Sun |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Tehran 35°41′N 51°25′E / 35.683°N 51.417°E | |||||

| Official languages | Persian | |||||

| Spoken languages[2] | ||||||

| Religion | Official: Shia Islam Other recognized religions: |

|||||

| Demonym | Iranian, Persian | |||||

| Government | Unitary theocratic presidential republic | |||||

| - | Supreme Leader | Ali Khamenei | ||||

| - | President | Hassan Rouhani | ||||

| - | Vice President | Eshaq Jahangiri | ||||

| Legislature | Islamic Consultative Assembly | |||||

| Unification[3] | ||||||

| - | Median Empire | c. 678 BC | ||||

| - | Achaemenid Empire | 550 BC | ||||

| - | Sassanid Empire[4] | 224 AD | ||||

| - | Safavid Empire | 1501[5] | ||||

| - | Islamic Republic | 1 April 1979 | ||||

| - | Current constitution | 24 October 1979 | ||||

| - | Constitution amendment | 28 July 1989 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 1,648,195 km2 (18th) 636,372 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.7 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2013 estimate | 78,192,200 [6] (17th) | ||||

| - | Density | 48/km2 (162rd) 124/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $1.284 trillion[7] (17th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $16,463[7] (72nd) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2014 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $402.700[7] (20th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $5,165[7] (98th) | ||||

| Gini (2010) | 38[8] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | high · 75th |

|||||

| Currency | Rial (﷼) (IRR) | |||||

| Time zone | IRST (UTC+3:30) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | IRDT (UTC+4:30) | ||||

| Date format | yyyy/mm/dd (SH) | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +98 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | IR | |||||

| Internet TLD |

|

|||||

Iran (![]() i/ɪˈrɑːn/[10] or /aɪˈræn/;[11] Persian: ایران - Irān [ʔiːˈɾɑn]), also known as Persia (/ˈpɜrʒə/ or /ˈpɜrʃə/),[11][12] officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a country in Western Asia.[13][14][15] It is bordered to the northwest by Armenia, the de facto independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, and Azerbaijan; with Kazakhstan and Russia across the Caspian Sea; to the northeast by Turkmenistan; to the east by Afghanistan and Pakistan; to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; and to the west by Turkey and Iraq. Comprising a land area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi), it is the second-largest nation in the Middle East and the 18th-largest in the world; with 78.4 million inhabitants, Iran is the world's 17th most populous nation.[13][16] It is the only country that has both a Caspian Sea and Indian Ocean coastline. Iran has long been of geostrategic importance because of its central location in Eurasia and Western Asia, and its proximity to the Strait of Hormuz.

i/ɪˈrɑːn/[10] or /aɪˈræn/;[11] Persian: ایران - Irān [ʔiːˈɾɑn]), also known as Persia (/ˈpɜrʒə/ or /ˈpɜrʃə/),[11][12] officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, is a country in Western Asia.[13][14][15] It is bordered to the northwest by Armenia, the de facto independent Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, and Azerbaijan; with Kazakhstan and Russia across the Caspian Sea; to the northeast by Turkmenistan; to the east by Afghanistan and Pakistan; to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman; and to the west by Turkey and Iraq. Comprising a land area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi), it is the second-largest nation in the Middle East and the 18th-largest in the world; with 78.4 million inhabitants, Iran is the world's 17th most populous nation.[13][16] It is the only country that has both a Caspian Sea and Indian Ocean coastline. Iran has long been of geostrategic importance because of its central location in Eurasia and Western Asia, and its proximity to the Strait of Hormuz.

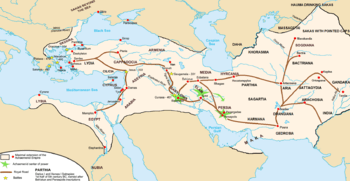

Iran is home to one of the world's oldest civilizations,[17][18] beginning with the formation of the Proto-Elamite and Elamite kingdom in 3200–2800 BC. The Iranian Medes unified the area into the first of many empires in 625 BC, after which it became the dominant cultural and political power in the region.[3] Iran reached the pinnacle of its power during the Achaemenid Empire (First Persian Empire) founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC, which at its greatest extent comprised major portions of the ancient world, stretching from parts of the Balkans (Bulgaria-Pannonia) and Thrace-Macedonia in the west, to the Indus Valley in the east, making it the largest empire the world had yet seen.[19] The empire collapsed in 330 BC following the conquests of Alexander the Great. The Parthian Empire emerged from the ashes and was succeeded by the Sasanian dynasty (Neo-Persian empire) in 224 AD, under which Iran again became one of the leading powers in the world, along with the Byzantine Empire, for the next four centuries.[20]

Rashidun Muslims invaded Persia in 633 AD, and conquered it by 651 AD, largely replacing Manichaeism and Zoroastrianism.[21] Iran thereafter played a vital role in the subsequent Islamic Golden Age, producing many influential scientists, scholars, artists, and thinkers. The emergence in 1501 of the Safavid dynasty, which promoted Twelver Shi'a Islam as the official religion, marked one of the most important turning points in Iranian and Muslim history.[5][22][23] Starting in 1736 under Nader Shah, Iran reached its greatest territorial extent since the Sassanid Empire, briefly possessing what was arguably the most powerful empire in the world.[24] The Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906 established the nation's first parliament, which operated within a constitutional monarchy. Following a coup d'état instigated by the U.K. and the U.S. in 1953, Iran gradually became autocratic. Growing dissent against foreign influence and political repression culminated in the Iranian Revolution, which led to the establishment of an Islamic republic on 1 April 1979.[16][25]

Tehran is the capital and largest city, serving as the cultural, commercial, and industrial center of the nation. Iran is a major regional and middle power,[26][27] exerting considerable influence in international energy security and the world economy through its large reserves of fossil fuels, which include the largest natural gas supply in the world and the fourth-largest proven oil reserves.[28][29] It hosts Asia's 4th-largest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.[30]

Iran is a founding member of the UN, NAM, OIC and OPEC. Its unique political system, based on the 1979 constitution, combines elements of a parliamentary democracy with a religious theocracy governed by the country's clergy, wherein the Supreme Leader wields significant influence. A multicultural nation comprising numerous ethnic and linguistic groups, most inhabitants are Shi'ites, the Iranian rial is the currency, and Persian is the official language.[31]

Etymology

The name of Iran is the Modern Persian derivative from the Proto-Iranian term Aryānā, meaning "Land of the Aryans", first attested in Zoroastrianism's Avesta tradition.[32][33][34][35] The term Ērān is found to refer to Iran in a 3rd-century Sassanid inscription, and the Parthian inscription that accompanies it uses the Parthian term "aryān" in reference to Iranians.[36]

Historically Iran has been referred to as "Persia" or similar (La Perse, Persien, Perzië, etc.) by the Western world, mainly due to the writings of Greek historians who called Iran Persis (Περσίς), meaning land of the Persians. As the most extensive and close interaction the Ancient Greeks ever had with any outsider was that with the Persians, the term became coined forever, even long after the Persian rule in Ancient Greece and beyond had ended and other dynasties were now ruling the regions. In 1935, Reza Shah requested that the international community refer to the country as Iran. As the New York Times explained at the time, "At the suggestion of the Persian Legation in Berlin, the Tehran government, on the Persian New Year, Nowruz, March 21, 1935, substituted Iran for Persia as the official name of the country. Defenders of the name change, point to its use by the Greek historians citing that "Aryan" means "noble". In truth during the rise and fall of the Persian Empire the land was known to its people as 'Aryanam', which is equated to the current “Iran” in the proto-Iranian language. During the reign of the Sassanids it became Eran – meaning "land of the Aryans".[37] Opposition to the name change led to the reversal of the decision, as also the work of Professor Ehsan Yarshater, editor of Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University, who propagated a move to use Persia and Iran interchangeably, which was approved by Mohammad Reza Shah.[38] Today both "Persia" and "Iran" are used interchangeably in cultural contexts; however, "Iran" is the name used officially in political contexts.[39]

The historical and cultural wider usage of "Iran" is not restricted to the modern state proper.[40][41][42] Irānshahr[43] or Irānzamīn (Greater Iran)[44] corresponded to territories of Iranian cultural or linguistic zones. Besides modern Iran, it included portions of the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, Anatolia, and Central Asia.[45]

History

Early history in Iran

The earliest archaeological artifacts in Iran, like those excavated at the Kashafrud and Ganj Par sites, attest to a human presence in Iran since the Lower Paleolithic era.[46] Neanderthal artifacts dating back to the Middle Paleolithic period have been found mainly in the Zagros region at sites such as Warwasi and Yafteh Cave.[47][48] Early agricultural communities such as Chogha Golan in 10,000 BC[49][50] began to flourish in Iran along with settlements such as Chogha Bonut in 8000 BC,[51][52] as well as Susa and Chogha Mish developing in and around the Zagros region.[53][54][55]

The emergence of Susa as a city is determined by C14 dating as early as 4395 BC.[56] There are dozens of pre-historic sites across the Iranian plateau pointing to the existence of ancient cultures and urban settlements in the 4th millennium BCE.[55][57][58] During the Bronze age Iran was home to several civilisations such as Elam, Jiroft and Zayandeh Rud civilisations. Elam, the most prominent of these civilisations developed in the southwest of Iran alongside those in Mesopotamia. The development of writing in Elam in 4th millennium BC paralleled that in Sumer.[59] The Elamite kingdom continued its existence until the emergence of the Median and Achaemenid Empires.

Classical Era

During the 2nd millennium BCE, Proto-Iranian tribes arrived in Iran from the Eurasian steppes,[61] rivaling the native settlers of the country.[62][63] As these tribes dispersed into the wider area of Greater Iran and beyond, the boundaries of modern Iran were dominated by the Persian, Parthian, and Median tribes. From the late 10th to late 7th centuries BC, these Iranian peoples, together with the pre Iranian kingdoms, fell under the domination of the Assyrian Empire, based in northern Mesopotamia.[64] Under king Cyaxares, the Medes and Persians entered into an alliance with Nabopolassar of Babylon, as well as the Scythians and the Cimmerians and together they attacked the Assyrian Empire. The civil war ravaged Assyrian Empire between 616 BC and 605 BC, thus freeing their respective peoples from three centuries of Assyrian rule.[64] The unification of the Median tribes under a single ruler in 728 BC led to the creation of a Median empire which, by 612 BC, controlled the whole of Iran as well as eastern Anatolia.[65]

In 550 BC, Cyrus the Great from the state of Anshan took over the Median empire, and founded the Achaemenid empire by unifying other city states. The conquest of Media was a result of what is called the Persian revolt; the brouhaha was initially triggered by the actions of the Median ruler Astyages and quickly spread to other provinces as they allied with the Persians. Later conquests under Cyrus and his successors expanded the empire to include Lydia, Babylon, Egypt, and the lands to the west of the Indus and Oxus rivers. At its greatest extent, the empire included the modern territories of Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, all significant population centers of ancient Egypt as far west as Libya, Turkey, Thrace and Macedonia, much of the Black Sea coastal regions, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, much of Central Asia, Afghanistan, northern Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and parts of Oman and the UAE, making it the first world empire.[66] Conflict on the western borders began with the famous Greco-Persian Wars which continued through the first half of the 5th century BC and ended with the Persian withdrawal from all of their European territories.[67] The empire had a centralised, bureaucratic administration under the Emperor and a large professional army and civil services, inspiring similar developments in later empires.[68]

In 334 BC, Alexander the Great invaded the Achaemenid Empire, defeating the last Achaemenid Emperor Darius III at the Battle of Issus in 333 BC. Following the premature death of Alexander, Iran came under the control of Hellenistic Seleucid Empire. In the middle of the 2nd century BC, the Parthian Empire rose to become the main power in Iran and continued as a feudal monarchy for nearly five centuries until 224 CE, when it was succeeded by the Sassanid Empire.[69] The Sassanids established an empire roughly within the frontiers achieved by the Achaemenids, with the capital at Ctesiphon, Tisfoon, and were alongside the Byzantines the two most dominant powers in the world for nearly four centuries.[70] Most of the period of the Parthian and Sassanid Empires were overshadowed by the Roman-Persian Wars, which raged on their western borders for over 700 years. These wars exhausted both Romans and Sassanids, which arguably led to the defeat of both at the hands of the invading Muslim Arabs.

Middle Ages (652–1501)

The prolonged Byzantine-Persian wars, as well as social conflict within the Empire opened the way for an Arab invasion of Iran in the 7th century.[71][72] Gundeshapur was the most important medical centre of the ancient world at the time of the Islamic conquest.[73] Initially defeated by the Arab Rashidun Caliphate, Iran later came under the rule of their successors the Arab Ummayad and Arab Abbasid Caliphates. The process of conversion of Iranians to Islam which followed was prolonged and gradual. Under the new Arab elite of the Rashidun and later Ummayad Caliphates Iranians, both Muslim (mawali) and non-Muslim (Dhimmi), were discriminated against, being excluded from government and military, and having to pay a special tax.[74][75] In 750 the Abbasids succeeded in overthrowing the Ummayad Caliphate, mainly due to the support from dissatisfied Iranian mawali.[76] The mawali formed the majority of the rebel army, which was led by the Iranian general Abu Muslim.[77][78][79] After two centuries of Arab rule semi-independent and independent Iranian kingdoms (such as the Tahirids, Saffarids, Samanids and Buyids) began to appear on the fringes of the declining Abbasid Caliphate. By the Samanid era in the 9th and 10th centuries Iran's efforts to regain its independence had been well solidified.[80]

The arrival of the Abbasid Caliphs saw a revival of Persian culture and influence, and a move away from Arabic culture. The role of the old Arab aristocracy was slowly replaced by a Persian bureaucracy.[81]

The blossoming Persian literature, philosophy, medicine, and art became major elements in the forming of a Muslim civilization during the Islamic Golden Age.[82][83] The Islamic Golden Age reached its peak in the 10th and 11th centuries, during which Persia was the main theatre of scientific activity.[73] After the 10th century, Persian, alongside Arabic, was used for scientific, philosophical, historical, mathematical, musical, and medical works, as important Iranian writers such as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Avicenna, Qotb al-Din Shirazi, Naser Khusraw and Biruni made contributions to Persian scientific writing.

The cultural revival that began in the Abbasid period led to a resurfacing of Iranian national identity, and so earlier attempts of Arabization never succeeded in Iran. The Iranian Shuubiyah movement became a catalyst for Iranians to regain their independence in their relations with the Arab invaders.[84] The most notable effect of the movement was the continuation of the Persian language attested to the epic poet Ferdowsi, now regarded as the most important figure in Persian literature.

The 10th century saw a mass migration of Turkic tribes from Central Asia into the Iranian plateau.[85] Turkic tribesmen were first used in the Abbasid army as slave-warriors (Mamluks), replacing Persian and Arab elements within the army.[77] As a result the Mamluks gained significant political power. In 999, large parts of Iran came briefly under the rule of the Ghaznavid dynasty, whose rulers were of Mamluk Turk origin, and longer subsequently under the Turkish Seljuk and Khwarezmian Empires. These Turks had been fully Persianised and had adopted Persian models of administration and rulership.[85]

The result of the adoption and patronage of Persian culture by Turkish rulers was the development of a distinct Turko-Persian tradition.

In 1219–21 the Khwarezmian Empire suffered a devastating invasion by Genghis Khan's Mongol army. According to Steven R. Ward, "Mongol violence and depredations killed up to three-fourths of the population of the Iranian Plateau, possibly 10 to 15 million people. Some historians have estimated that Iran's population did not again reach its pre-Mongol levels until the mid-20th century."[86] Following the fracture of the Mongol Empire in 1256 Hulagu Khan, Genghis Khan's grandson, established the Ilkhanate dynasty in Iran. In 1370 yet another conqueror, Timur, commonly known as Tamerlane in the West, followed Hulagu's example, establishing the Timurid Dynasty which lasted for another 156 years. In 1387, Timur ordered the complete massacre of Isfahan, reportedly killing 70,000 citizens.[87] Hulagu, Timur and their successors soon came to adopt the ways and customs of the Persians, choosing to surround themselves with a culture that was distinctively Persian.[88]

Dynasties (1501–1979)

At the start of the 1500s, Shah Ismail I established the Safavid Dynasty in western Persia and Azerbaijan.[85] He subsequently extended his authority over all of Persia, and established intermittent Persian hegemony over vast nearby regions which would last for many centuries onwards. Ismail instigated a forced conversion from Sunni to Shi'a Islam.[89] The rivalry between Safavid Persia and the Ottoman Empire led to numerous Ottoman–Persian Wars.[86] The Safavid era peaked in the reign of the brilliant soldier, statesman and administrator Shah Abbas I (1587–1629),[23][86] surpassing their Ottoman arch rivals in strength, and making the empire a leading hub in Western Eurasia for the sciences and arts. The Safavid era also saw the start of the creation of new layers in Persian society, composed of hundreds of thousands of ethnic Georgians, Circassians, Armenians, and other peoples of the Caucasus. Following a slow decline in the late 1600s and early 1700s by internal strife, royal intrigues, continuous wars between them and their Ottoman arch rivals, and foreign interference (most notably by the Russians) the Safavid dynasty was ended by Pashtun rebels who besieged Isfahan and defeated Soltan Hosein in 1722.

In 1729, an Iranian Khorasan chieftain and military genius, Nader Shah, successfully drove out, then conquered the Pashtun invaders.

During Nader Shah's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sassanian Empire, reestablishing Persian hegemony over all of the Caucasus, other major parts of West Asia, Central Asia and parts of South Asia, and briefly possessing what was arguably the most powerful empire in the world.[24]

In 1738-39, he invaded India and sacked Delhi, bringing great loot back to Persia. Nader Shah's assassination sparked a brief period of civil war and turmoil, after which Karim Khan came to power in 1750, bringing a period of relative peace and prosperity.[86]

Another civil war ensued after Karim Khan's death in 1779, out of which Aga Muhammad Khan emerged victorious, founding the Qajar Dynasty in 1794. In 1795, following the disobedience of their Georgian subjects and their alliance with the Russians, the Qajars sacked and ravaged Tblisi, and drove the Russians out of the entire Caucasus, reestablishing Persian suzerainty over the region. However reestablishment of Persian control was short-lived, and the Russo-Persian War (1804–13) and the Russo-Persian War (1826–28) resulted in large irrevocable territorial losses for Persia but substantial gains for the Russian Empire which took over the Caucasus (modern Dagestan, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan) from Iran as a result of the treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay.[91] Apart from Agha Mohammad Khan rule, Qajar rule is characterised as a century of misrule.[85]

Around 1.5 million people, or 20–25% of Persia's population, died as a result of the Great Persian Famine of 1870–1871.[92]

Whilst resisting efforts to be colonised, Iran lost lands in the 1800s as a result of Russian and British empire-building, known as 'The Great Game', losing much of its territory in the Russo-Persian and the Anglo-Persian Wars. A series of protests took place in response to the sale of concessions to foreigners by Nasser al-Din Shah and Mozaffar ad-Din Shah between 1872 and 1905, the last of which resulted in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution and establishment of Iran's first national parliament in 1906, which was abolished in 1908. The struggle continued until 1911, when Mohammad Ali was defeated and forced to abdicate. On the pretext of restoring order, the Russians occupied northern Iran in 1911. During World War I, the British occupied much of western Iran, not fully withdrawing until 1921.

In 1921, Reza Khan, Prime Minister of Iran and former general of the Persian Cossack Brigade, overthrew the Qajar Dynasty and became Shah. In 1941 he was forced to abdicate in favour of his son, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, after Iran came under British and Russian occupation following the Anglo-Soviet invasion that established the Persian Corridor and would last until 1946.

In 1951 Mohammad Mosaddegh was elected prime minister. He became enormously popular in Iran after he nationalized Iran's petroleum industry and oil reserves. He was deposed in the 1953 Iranian coup d'état, an Anglo-American covert operation that marked the first time the US had overthrown a foreign government during the Cold War.[93]

After the coup, the Shah became increasingly autocratic and Sultanistic. Arbitrary arrests and torture by his secret police, SAVAK, were used to crush all forms of political opposition. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became an active critic of the Shah's White Revolution and publicly denounced the government. Khomeini was arrested and imprisoned for 18 months. After his release in 1964, Khomeini publicly criticized the United States government. The Shah sent him into exile. He went first to Turkey, then to Iraq and finally to France.

Due to the 1973 spike in oil prices Iran’s economy was flooded with foreign currency which caused inflation. By 1974 Iran’s economy was experiencing double digit inflation and despite many large projects to modernize the country corruption was rampant and caused large amounts of waste. By 1975 and 1976 an economic recession led to increased unemployment, especially among millions of young men who had migrated to Iran’s cities looking for construction jobs during the boom years of the early 1970s. By 1977 many of these men opposed the shah’s regime and began to organize and join protests against it.[94]

After the Iranian Revolution (1979–)

The Iranian Revolution, later known as the Islamic Revolution,[95][96][97] began in January 1978 with the first major demonstrations against the Shah.[98] After a year of strikes and demonstrations paralyzed the country and its economy the Shah fled the country and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned from exile to Tehran in February 1979.[99] A new government was formed and in April 1979 Iran officially became an Islamic Republic, after its establishment was supported in a referendum.[16][25] A second referendum in December 1979 approved a theocratic constitution.[100]

Almost immediately nationwide uprisings against the new regime began in Iranian Kurdistan, Khuzestan, Balochistan and other areas. Over the next several years these uprisings were subdued in a violent manner by the new Islamic government. The new government went about purging itself of the non-Islamist political opposition (e.g. although both nationalists and Marxists had initially joined with Islamists to overthrow the Shah, tens of thousands were executed by the Islamic regime afterward).[101]

On March 8, 1979, coinciding with International Women's Day, many Iranian women demonstrated against perceived reductions to the status and rights of women, especially with regard to family law and mandatory veiling.[102] The Iranian Cultural Revolution began in 1980 and universities were closed by the theocratic regime.

On 4 November 1979, a group of Iranian students seized the U.S. embassay and took 52 US citizens and embassy personnel hostage[103] after the US refused to return the former Shah to Iran to face trial and execution. Attempts by the Jimmy Carter administration to negotiate for the release of the hostages and a failed rescue attempt helped force Carter out of office and brought Ronald Reagan to power. On Jimmy Carter's final day in office the last hostages were finally set free as a result of the Algiers Accords.

On 22 September 1980 the Iraqi army invaded Iranian Khuzestan, the start of the Iran–Iraq War. Although Saddam Hussein's forces made several early advances, by mid 1982 the Iranian forces successfully managed to drive the Iraqi army back into Iraq. In July 1982 with Iraq thrown on the defensive, Iran took the decision to invade Iraq and conducted countless offensives in a bid to conquer Iraqi territory and capture cities, such as Basra. The war continued until 1988, when Iraqi army defeated the Iranian forces inside Iraq and pushed the remaining Iranian troops back across the border, subsequently Khomeini accepted a truce mediated by the UN. The total Iranian casualties in the war were estimated to be 123,220–160,000 KIA, 60,711 MIA and 11,000-16,000 civilians killed.[104][105]

Following the Iran–Iraq War, President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani and his administration (1989-1997) concentrated on a pragmatic pro-business policy of rebuilding and strengthening the economy without making any dramatic break with the ideology of the revolution. Rafsanjani was succeeded by the moderate reformist Mohammad Khatami whose government (1997-2005) attempted, unsuccessfully, to make the country more free and democratic.[106]

The 2005 presidential election brought the conservative populist candidate, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, to power.[107] During the 2009 Iranian presidential election the Interior Ministry announced incumbent president Ahmadinejad had won 62.63% of the vote, while Mir-Hossein Mousavi had come in second place with 33.75%.[108][109] Allegations of large irregularities and fraud provoked the 2009 Iranian presidential election protests both within Iran and in major cites outside the country.[110]

Hassan Rouhani was elected as President of Iran on 15 June 2013, defeating Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf and four other candidates.[111][112] The electoral victory of new Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has improved Iran's relations with other countries.[113]

Geography

Iran is the 18th largest country in the world, with an area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,372 sq mi).[29] Its area roughly equals that of the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Germany combined, or somewhat more than the US state of Alaska.[114] Iran lies between latitudes 24° and 40° N, and longitudes 44° and 64° E. Its borders are with Azerbaijan (611 km (380 mi)) (with Azerbaijan-Naxcivan exclave (179 km (111 mi) ))[115] and Armenia (35 km (22 mi)) to the north-west; the Caspian Sea to the north; Turkmenistan (992 km (616 mi)) to the north-east; Pakistan (909 km (565 mi)) and Afghanistan (936 km (582 mi)) to the east; Turkey (499 km (310 mi)) and Iraq (1,458 km (906 mi)) to the west; and finally the waters of the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman to the south.

Iran consists of the Iranian Plateau with the exception of the coasts of the Caspian Sea and Khuzestan Province. It is one of the world's most mountainous countries, its landscape dominated by rugged mountain ranges that separate various basins or plateaux from one another. The populous western part is the most mountainous, with ranges such as the Caucasus, Zagros and Alborz Mountains; the last contains Iran's highest point, Mount Damavand at 5,610 m (18,406 ft), which is also the highest mountain on the Eurasian landmass west of the Hindu Kush.[116]

The northern part of Iran is covered by dense rain forests called Shomal or the Jungles of Iran. The eastern part consists mostly of desert basins such as the Dasht-e Kavir, Iran's largest desert, in the north-central portion of the country, and the Dasht-e Lut, in the east, as well as some salt lakes. This is because the mountain ranges are too high for rain clouds to reach these regions.

The only large plains are found along the coast of the Caspian Sea and at the northern end of the Persian Gulf, where Iran borders the mouth of the Arvand river. Smaller, discontinuous plains are found along the remaining coast of the Persian Gulf, the Strait of Hormuz and the Gulf of Oman.

-

Aerial view of Mount Damavand

-

Laton Jungle in Gilan

-

Haraz River in Amol

-

Zayanderud and Khajoo Bridge over it in Isfahan City

-

Alvand peak

Climate

.png)

| Hot desert climate Cold desert climate Hot semi-arid climate Cold semi-arid climate Hot-summer Mediterranean climate Continental Mediterranean climate |

Iran's climate ranges from arid or semiarid, to subtropical along the Caspian coast and the northern forests. On the northern edge of the country (the Caspian coastal plain) temperatures rarely fall below freezing and the area remains humid for the rest of the year. Summer temperatures rarely exceed 29 °C (84.2 °F).[117][118] Annual precipitation is 680 mm (26.8 in) in the eastern part of the plain and more than 1,700 mm (66.9 in) in the western part. United Nations Resident Coordinator for Iran Gary Lewis has said that "Water scarcity poses the most severe human security challenge in Iran today".[119]

To the west, settlements in the Zagros basin experience lower temperatures, severe winters with below zero average daily temperatures and heavy snowfall. The eastern and central basins are arid, with less than 200 mm (7.9 in) of rain, and have occasional deserts.[118] Average summer temperatures exceed 38 °C (100.4 °F). The coastal plains of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman in southern Iran have mild winters, and very humid and hot summers. The annual precipitation ranges from 135 to 355 mm (5.3 to 14.0 in).[118]

Fauna

Iran's wildlife is composed of several animal species including bears, gazelles, wild pigs, wolves, jackals, panthers, Eurasian lynx, and foxes.

Domestic animals include sheep, goats, cattle, horses, water buffalo, donkeys, and camels. The pheasant, partridge, stork, eagles and falcon are also native to Iran.

One of the most famous members of Iranian wildlife is the critically endangered Asiatic cheetah, also known as the Iranian Cheetah, whose numbers were greatly reduced after the Iranian Revolution.

Today there are ongoing efforts to increase its population and introduce it back in India. Iran had lost all its Asiatic Lion and the now extinct Caspian Tigers by the earlier part of the 20th century.[120]

Regions, provinces and cities

Azerbaijan

Iran is divided into five regions with thirty one provinces (ostān),[121] each governed by an appointed governor (ostāndār). The provinces are divided into counties (shahrestān), and subdivided into districts (bakhsh) and sub-districts (dehestān).

Iran has one of the highest urban growth rates in the world. From 1950 to 2002, the urban proportion of the population increased from 27% to 60%.[122] The United Nations predicts that by 2030, 80% of the population will be urban.[123] Most internal migrants have settled near the cities of Tehran, Isfahan, Ahvaz, and Qom. The listed populations are from the 2006/07 (1385 AP) census.[124] Tehran, with a population of 7,705,036, is the largest city in Iran and is the capital. Tehran, like many big cities, suffers from severe air pollution. It is the hub of the country's communication and transport network.

Mashhad, with a population of 2,410,800, is the second largest Iranian city and the centre of the Razavi Khorasan Province. Mashhad is one of the holiest Shia cities in the world as it is the site of the Imam Reza shrine. It is the centre of tourism in Iran, and between 15 and 20 million pilgrims go to the Imam Reza's shrine every year.[125][126]

Another major Iranian city is Isfahan (population 1,583,609), which is the capital of Isfahan Province. The Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Isfahan has been designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. The city contains a wide variety of Islamic architectural sites ranging from the 11th to the 19th century. The growth of the suburban area around the city has turned Isfahan into Iran's second most populous metropolitan area (3,430,353).[127]

The fourth major city of Iran is Tabriz (population 1,378,935), the capital of the East Azerbaijan Province. It is also the second industrial city of Iran after Tehran. Tabriz had been the second largest city in Iran until the late 1960s and one of its former capitals and residence of the crown prince under the Qajar dynasty. The city has proven extremely influential in the country’s recent history.

The fifth major city is Karaj (population 1,377,450), located in Alborz Province and situated 20 km west of Tehran, at the foot of the Alborz mountains; however, the city is increasingly becoming an extension of metropolitan Tehran.

The sixth major Iranian city is Shiraz (population 1,214,808); it is the capital of Fars Province. The Elamite civilization to the west greatly influenced the area, which soon came to be known as Persis. The ancient Persians were present in the region from about the 9th century BC, and became rulers of a large empire under the Achaemenid dynasty in the 6th century BC. The ruins of Persepolis and Pasargadae, two of the four capitals of the Achaemenid Empire, are located in or near Shiraz. Persepolis was the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire and is situated 70 kilometres (43 mi) northeast of modern Shiraz. UNESCO declared the citadel of Persepolis a World Heritage Site in 1979.

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Tehran  Mashhad |

1 | Tehran | Tehran | 8,244,759 | 11 | Urmia | West Azarbaijan | 680,228 |  Isfahan  Karaj |

| 2 | Mashhad | Razavi Khorasan | 2,772,287 | 12 | Zahedan | Sistan and Baluchestan | 575,116 | ||

| 3 | Isfahan | Isfahan | 1,978,168 | 13 | Yazd | Yazd | 550,904 | ||

| 4 | Karaj | Alborz | 1,967,005 | 14 | Hamadan | Hamadan | 548,378 | ||

| 5 | Shiraz | Fars | 1,549,453 | 15 | Arak | Markazi | 536,572 | ||

| 6 | Tabriz | East Azarbaijan | 1,545,491 | 16 | Kerman | Kerman | 534,441 | ||

| 7 | Ahwaz | Khuzestan | 1,133,003 | 17 | Ardabil | Ardabil | 485,153 | ||

| 8 | Qom | Qom | 1,095,871 | 18 | Bandar Abbas | Hormozgan | 448,861 | ||

| 9 | Kermanshah | Kermanshah | 857,048 | 19 | Eslamshahr | Tehran | 389,102 | ||

| 10 | Rasht | Gilan | 698,014 | 20 | Zanjan | Zanjan | 388,796 | ||

Government and politics

The political system of the Islamic Republic is based on the 1979 Constitution, and comprises several intricately connected governing bodies. The Leader of the Revolution ("Supreme Leader") is responsible for delineation and supervision of the general policies of the Islamic Republic of Iran.[129] The Supreme Leader is Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, controls the military intelligence and security operations; and has sole power to declare war or peace.[129] The heads of the judiciary, state radio and television networks, the commanders of the police and military forces and six of the twelve members of the Guardian Council are appointed by the Supreme Leader.[129] The Assembly of Experts elects and dismisses the Supreme Leader on the basis of qualifications and popular esteem.[130]

After the Supreme Leader, the Constitution defines the President of Iran as the highest state authority.[129][131] The President is elected by universal suffrage for a term of four years and can only be re-elected for one term.[131] Presidential candidates must be approved by the Guardian Council prior to running in order to ensure their allegiance to the ideals of the Islamic revolution.[132]

The President is responsible for the implementation of the Constitution and for the exercise of executive powers, except for matters directly related to the Supreme Leader, who has the final say in all matters.[129] The President appoints and supervises the Council of Ministers, coordinates government decisions, and selects government policies to be placed before the legislature.[133] Eight Vice-Presidents serve under the President, as well as a cabinet of twenty-two ministers, who must all be approved by the legislature.[134]

The legislature of Iran (known in English as the Islamic Consultative Assembly) is a unicameral body.[135] The Parliament of Iran comprises 290 members elected for four-year terms.[135] The parliament drafts legislation, ratifies international treaties, and approves the national budget. All parliament candidates and all legislation from the assembly must be approved by the Guardian Council.[136]

The Guardian Council comprises twelve jurists including six appointed by the Supreme Leader. The others are elected by the Iranian Parliament from among the jurists nominated by the Head of the Judiciary.[137][138] The Council interprets the constitution and may veto Parliament. If a law is deemed incompatible with the constitution or Sharia (Islamic law), it is referred back to Parliament for revision.[131] The Expediency Council has the authority to mediate disputes between Parliament and the Guardian Council, and serves as an advisory body to the Supreme Leader, making it one of the most powerful governing bodies in the country.[139] Local city councils are elected by public vote to four-year terms in all cities and villages of Iran.

Law

The Supreme Leader appoints the head of Iran's judiciary, who in turn appoints the head of the Supreme Court and the chief public prosecutor.[140] There are several types of courts including public courts that deal with civil and criminal cases, and revolutionary courts which deal with certain categories of offenses, including crimes against national security. The decisions of the revolutionary courts are final and cannot be appealed.[140] The Special Clerical Court handles crimes allegedly committed by clerics, although it has also taken on cases involving lay people. The Special Clerical Court functions independently of the regular judicial framework and is accountable only to the Supreme Leader. The Court's rulings are final and cannot be appealed.[140] The Assembly of Experts, which meets for one week annually, comprises 86 "virtuous and learned" clerics elected by adult suffrage for eight-year terms. As with the presidential and parliamentary elections, the Guardian Council determines candidates' eligibility.[140] The Assembly elects the Supreme Leader and has the constitutional authority to remove the Supreme Leader from power at any time.[140] It has not challenged any of the Supreme Leader's decisions.[140]

The state-owned Telecommunication Company of Iran handles telecommunications. The media of Iran is a mixture of private and state-owned, but books and movies must be approved by the The ministry of Ershaad before being released to the public. Iran originally received access to the internet in 1993, and it has become enormously popular among the Iranian youth.

Foreign relations

.jpg)

The Iranian government's officially stated goal is to establish a new world order based on world peace, global collective security and justice[144][145] although the current Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, had stated that these terms should be understood in the context of the Shia Islamic belief system.[146] Iran's foreign relations are based on two strategic principles: eliminating outside influences in the region and pursuing extensive diplomatic contacts with developing and non-aligned countries.

As of 2009 Iran maintained full diplomatic relations with 99 countries worldwide[147] but not the U.S. or Israel (which Iran does not officially recognize).[148] Iran is also a member of dozens of international organizations including the G-15, G-24, G-77, IAEA, IBRD, IDA, IDB, IFC, ILO, IMF, International Maritime Organization, Interpol, OIC, OPEC,[149] the United Nations, WHO, and currently has observer status at the World Trade Organization.

Since 2005, Iran's nuclear program has become the subject of contention with the international community. Many countries have expressed concern that Iran's nuclear program could divert civilian nuclear technology into a weapons program. This has led the UN Security Council to impose sanctions against Iran which has further isolated Iran politically, economically and socially from the rest of the global community. Following the departure of Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from power the 2013 Geneva Agreement was signed and provided for a temporary lifting of some sanctions and on 2 April 2015 a comprehensive agreement was reached.

Military

The Islamic Republic of Iran has two types of armed forces: the regular forces Islamic Republic of Iran Army, Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force, Islamic Republic of Iran Navy and the Revolutionary Guards, totaling about 545,000 active troops. Iran also has around 350,000 Reserve Force totaling around 900,000 trained troops.[150] Iran has a paramilitary, volunteer militia force within the IRGC, called the Basij, which includes about 90,000 full-time, active-duty uniformed members. Up to 11 million men and women are members of the Basij who could potentially be called up for service; GlobalSecurity.org estimates Iran could mobilize "up to one million men". This would be among the largest troop mobilizations in the world.[151] In 2007, Iran's military spending represented 2.6% of the GDP or $102 per capita, the lowest figure of the Persian Gulf nations.[152] Iran's military doctrine is based on deterrence.[153]

Since the Iranian Revolution, to overcome foreign embargo, Iran has developed its own military industry, produced its own tanks, armored personnel carriers, guided missiles, submarines, military vessels, guided missile destroyer, radar systems, helicopters and fighter planes.[154][155][156] In recent years, official announcements have highlighted the development of weapons such as the Hoot, Kowsar, Zelzal, Fateh-110, Shahab-3 and Sejjil missiles, and a variety of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs).[157] The Fajr-3 (MIRV) is currently Iran's most advanced ballistic missile, it is a liquid fuel missile with an undisclosed range which was developed and produced domestically.

Economy

Iran's economy is a mixture of central planning, state ownership of oil and other large enterprises, village agriculture, and small-scale private trading and service ventures.[158] In 2011 GDP was $482.4 billion ($1.003 trillion at PPP), or $13,200 at PPP per capita.[29] Iran is ranked as an upper-middle income economy by the World Bank.[159] In the early 21st century the service sector contributed the largest percentage of the GDP, followed by industry (mining and manufacturing) and agriculture.[160] The Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran is responsible for developing and maintaining the Iranian rial, which serves as the country's currency. The government doesn't recognize trade unions other than the Islamic Labour Councils, which are subject to the approval of employers and the security services.[161] The minimum wage in June 2013 was 487 million rials a month ($134).[162] Unemployment has remained above 10% since 1997, and the unemployment rate for women is almost double that of the men.[162]

In 2006, about 45% of the government's budget came from oil and natural gas revenues, and 31% came from taxes and fees.[163] As of 2007, Iran had earned $70 billion in foreign exchange reserves mostly (80%) from crude oil exports.[164] Iranian budget deficits have been a chronic problem, mostly due to large-scale state subsidies, that include foodstuffs and especially gasoline, totaling more than $84 billion in 2008 for the energy sector alone.[165][166] In 2010, the economic reform plan was approved by parliament to cut subsidies gradually and replace them with targeted social assistance. The objective is to move towards free market prices in a 5-year period and increase productivity and social justice.[167]

The administration continues to follow the market reform plans of the previous one and indicated that it will diversify Iran's oil-reliant economy. Iran has also developed a biotechnology, nanotechnology, and pharmaceuticals industry.[168] However, nationalized industries such as the bonyads have often been managed badly, making them ineffective and uncompetitive with years. Currently, the government is trying to privatize these industries, and, despite successes, there are still several problems to be overcome, such as the lagging corruption in the public sector and lack of competitiveness. In 2010, Iran was ranked 69, out of 139 nations, in the Global Competitiveness Report.[169]

Iran has leading manufacturing industries in the fields of car-manufacture and transportation, construction materials, home appliances, food and agricultural goods, armaments, pharmaceuticals, information technology, power and petrochemicals in the Middle East.[170] According to FAO, Iran has been a top five producer of the following agricultural products in the world in 2012: apricots, cherries, sour cherries, cucumbers and gherkins, dates, eggplants, figs, pistachios, quinces, walnuts, and watermelons.[171]

Economic sanctions against Iran, such as the embargo against Iranian crude oil, have affected the economy.[172] Sanctions have led to a steep fall in the value of the rial, and as of April 2013 one US dollar is worth 36,000 rial, compared with 16,000 in early 2012.[173]

Tourism

Although tourism declined significantly during the war with Iraq, it has subsequently recovered. About 1,659,000 foreign tourists visited Iran in 2004 and 2.3 million in 2009 mostly from Asian countries, including the republics of Central Asia, while about 10% came from the European Union and North America.[174][175][176]

The most popular tourist destinations are Isfahan, Mashhad and Shiraz.[177] In the early 2000s the industry faced serious limitations in infrastructure, communications, industry standards and personnel training.[178] The majority of the 300,000 tourist visas granted in 2003 were obtained by Asian Muslims, who presumably intended to visit important pilgrimage sites in Mashhad and Qom.[176] Several organized tours from Germany, France and other European countries come to Iran annually to visit archaeological sites and monuments. In 2003 Iran ranked 68th in tourism revenues worldwide.[179] According to UNESCO and the deputy head of research for Iran Travel and Tourism Organization (ITTO), Iran is rated among the "10 most touristic countries in the world".[179] Domestic tourism in Iran is one of the largest in the world.[175][180][181] Weak advertising, unstable regional conditions, a poor public image in some parts of the world, and absence of efficient planning schemes in the tourism sector have all hindered the growth of tourism.

Energy

Iran has the largest proved gas reserves in the world, with 33.6 trillion cubic metres.[28] It also ranks fourth in oil reserves with an estimated 153,600,000,000 barrels.[182][183] It is OPEC's 2nd largest oil exporter and is an energy superpower.[184][185] In 2005, Iran spent US$4 billion on fuel imports, because of contraband and inefficient domestic use.[186] Oil industry output averaged 4 million barrels per day (640,000 m3/d) in 2005, compared with the peak of six million barrels per day reached in 1974. In the early years of the 2000s (decade), industry infrastructure was increasingly inefficient because of technological lags. Few exploratory wells were drilled in 2005.

In 2004, a large share of natural gas reserves in Iran were untapped. The addition of new hydroelectric stations and the streamlining of conventional coal and oil-fired stations increased installed capacity to 33,000 megawatts. Of that amount, about 75% was based on natural gas, 18% on oil, and 7% on hydroelectric power. In 2004, Iran opened its first wind-powered and geothermal plants, and the first solar thermal plant is to come online in 2009. Iran is the third country in the world to have developed GTL technology.[187]

Demographic trends and intensified industrialization have caused electric power demand to grow by 8% per year. The government’s goal of 53,000 megawatts of installed capacity by 2010 is to be reached by bringing on line new gas-fired plants and by adding hydroelectric, and nuclear power generating capacity. Iran’s first nuclear power plant at Bushehr went online in 2011. It is the second Nuclear Power Plant that ever built in the Middle East after Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant in Armenia.[188][189]

Education and science

Education in Iran is highly centralized. K-12 education is supervised by the Ministry of Education, and higher education is under the supervision of the Ministry of Science and Technology. The adult literacy rate in 2008 was 85.0%, up from 36.5% in 1976.[190]

The requirement to enter into higher education is to have a high school diploma and pass the national university entrance examination, Iranian University Entrance Exam (known as concour), which is the equivalent of the US SAT exams. Many students do a 1-2 year course of pre-university (piš-dānešgah), which is the equivalent of GCE A-levels and International Baccalaureate. The completion of the pre-university course earns students the Pre-University Certificate.[191] Iran is the only country in the Middle East with a high school course equivalent to the A-levels, SAT and International Baccalaureate.

Higher education is sanctioned by different levels of diplomas. Kārdāni (associate degree; also known as fowq e diplom) is delivered after 2 years of higher education; kāršenāsi (bachelor's degree; also known as licāns) is delivered after 4 years of higher education; and kāršenāsi e aršad (master's degree) is delivered after 2 more years of study, after which another exam allows the candidate to pursue a doctoral program (PhD; known as doctorā).[192]

According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are the University of Tehran (468th worldwide), the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (612th) and Ferdowsi University of Mashhad (815th).[193]

Iran has increased its publication output nearly tenfold from 1996 through 2004, and has been ranked first in terms of output growth rate, followed by China.[194] According to SCImago, Iran could rank fourth in the world in terms of research output by 2018, if the current trend persists.[195]

In 2009, a SUSE Linux-based HPC system made by the Aerospace Research Institute of Iran (ARI) was launched with 32 cores, and now runs 96 cores. Its performance was pegged at 192 GFLOPS.[196] Sorena 2 Robot, which was designed by engineers at the University of Tehran, was unveiled in 2010. The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) has placed the name of Surena among the five prominent robots of the world after analyzing its performance.[197]

In the biomedical sciences, Iran's Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics is a UNESCO chair in biology.[198] In late 2006, Iranian scientists successfully cloned a sheep by somatic cell nuclear transfer, at the Royan Research Center in Tehran.[199]

According to a study by David Morrison and Ali Khadem Hosseini (Harvard-MIT and Cambridge), stem cell research in Iran is amongst the top 10 in the world.[200] Iran ranks 15th in the world in nanotechnologies.[201][202][203]

Iran placed its domestically built satellite, Omid into orbit on the 30th anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, on 2 February 2009,[204] through Safir rocket, becoming the ninth country in the world capable of both producing a satellite and sending it into space from a domestically made launcher.[205]

The Iranian nuclear program was launched in the 1950s. Iran is the seventh country to produce uranium hexafluoride, and controls the entire nuclear fuel cycle.[206][207]

Iranian scientists outside Iran have also made some major contributions to science. In 1960, Ali Javan co-invented the first gas laser, and fuzzy set theory was introduced by Lotfi Zadeh.[208] Iranian cardiologist, Tofy Mussivand invented and developed the first artificial cardiac pump, the precursor of the artificial heart. Furthering research and treatment of diabetes, HbA1c was discovered by Samuel Rahbar. Iranian physics is especially strong in string theory, with many papers being published in Iran.[209] Iranian-American string theorist Kamran Vafa proposed the Vafa-Witten theorem together with Edward Witten. In August 2014, Maryam Mirzakhani became the first-ever woman, as well as the first-ever Iranian, to receive the Fields Medal, the highest prize in mathematics.[210]

Demographics

| 1956-2011 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1956 | 18,954,704 | — |

| 1966 | 25,785,210 | +3.13% |

| 1976 | 33,708,744 | +2.72% |

| 1986 | 49,445,010 | +3.91% |

| 1996 | 60,055,488 | +1.96% |

| 2006 | 70,495,782 | +1.62% |

| 2011 | 75,149,669 | +1.29% |

| Source: United Nations Demographic Yearbook[211] | ||

Iran is a diverse country, consisting of many religious and ethnic groups that are unified through a shared Persian language and culture.[212]

Iran's population grew rapidly during the latter half of the 20th century, increasing from about 19 million in 1956 to around 75 million by 2009.[213][214] However, Iran's birth rate has dropped significantly in recent years, leading to a population growth rate—recorded from July 2012—of about 1.29 percent.[215] Studies project that Iran's rate of growth will continue to slow until it stabilizes above 105 million by 2050.[216][217]

Iran hosts one of the largest refugee populations in the world, with more than one million refugees, mostly from Afghanistan and Iraq.[218] Since 2006, Iranian officials have been working with the UNHCR and Afghan officials for their repatriation.[219] According to estimates, about five million Iranian citizens have emigrated to other countries, mostly since the Iranian Revolution in 1979.[220][221]

According to the Iranian Constitution, the government is required to provide every citizen of the country with access to social security that covers retirement, unemployment, old age, disability, accidents, calamities, health and medical treatment and care services. This is covered by tax revenues and income derived from public contributions. According to the World Health Organization, Iran ranked 58th in national health metrics and 93rd in the overall performance of its healthcare system in 2000.[222]

Languages

The majority of the population speaks the Persian language, which is also the official language of the country. Others include the rest of the Iranian languages belonging to the Indo-Iranian branch of the Indo-European languages, and the languages of the other ethnicities in Iran.

In southwestern and southern Iran, the Luri and Lari languages are spoken. In Kurdistan Province and nearby areas, Kurdish is widely spoken. In Khuzestan, many distinct Persian dialects are spoken.

Turkic languages and dialects, most importantly the Azerbaijani language, are spoken in different areas in Iran. Arabic is also spoken by the Arabs of Khuzestan.

Notable minority languages in Iran include Armenian, Georgian, and Neo-Aramaic. Circassian was also once widely used by the large Circassian minority, but, due to assimilation over the many years, no sizable number of Circassians speak the language anymore.[223][224][225][226]

Ethnic groups

The CIA World Factbook has estimated that around 79% of the population of Iran are a diverse Indo-European ethno-linguistic group that comprise the speakers of the Iranian languages,[227] with Persians constituting 61% of the population, Kurds 10%, Lurs 6%, and Balochs 2%. Peoples of the other ethnicities in Iran make up the remaining 21%, with Azerbaijanis constituting 16%, Arabs 2%, Turkmens and Turkic tribes 2%, and others 1% (such as Armenians, Georgians, Circassians, and Assyrians).[29] It found Persian to be the first language of 53% of the population, Azeri and other Turkic dialects being spoken by 18%, Kurdish by 10%, Gilaki and Mazandarani by 7%, Luri by 6%, Balochi by 2%, Arabic by 2%, and other languages at 2%.[29]

The Library of Congress issued slightly different estimates: Persians 65%, Azerbaijanis 16%, Kurds 7%, Lurs 6%, Arabs 2%, Baluchi 2%, Turkmens 1%, Turkic tribal groups such as the Qashqai 1%, and non-Iranian, non-Turkic groups such as Armenians, Georgians, Assyrians, and Circassians less than 1%. It determined that Persian is the first language of at least 65% of the country's population and is the second language for most of the remaining 35%.[228]

Religion

| Religion | % of population | No. of people |

|---|---|---|

| Muslim | 99.4% | 74,682,938 |

| Not declared | 0.4% | 205,317 |

| Christian | 0.16% | 117,704 |

| Zoroastrian | 0.03% | 25,271 |

| Jew | 0.01% | 8,756 |

| Other | 0.07% | 49,101 |

Historically, Zoroastrianism was the dominant religion in Iran, particularly during the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanid empires. This changed after the fall of the Sassanid Empire by the Muslim Conquest of Iran, when Zoroastrianism was gradually replaced with Islam.

Today, the Twelver Shia branch of Islam is the official state religion, to which about 90% to 95%[230][231] of Iranians officially are. About 4% to 8% of Iranians are Sunni Muslims, mainly Kurds and Balochs. The remaining 2% are non-Muslim religious minorities, including Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, Bahais, Mandeans, Yezidis, and Yarsanis.[29][232]

Zoroastrians are the oldest religious community of the nation, with a long history continuing up to the present day.

Judaism also has a long history in Iran, dating back to the Achaemenid Conquest of Babylonia. Although many left in the wake of the establishment of the State of Israel and the 1979 Revolution, around 8,756 Jews remain in Iran, according to the latest census.[233]

Around 250,000 - 370,000 Christians reside in Iran.[234][235] Most are of Armenian background with a sizable minority of Assyrians as well.[236]

Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity and Sunni Islam are officially recognized by the government, and have reserved seats in the Iranian Parliament. But the Bahá'í Faith, which is said to be the largest religious minority in Iran,[237] is not officially recognized, and has been persecuted during its existence in Iran since the 19th century. Since the 1979 Revolution, the persecution of Bahais has increased with executions, the denial of civil rights and liberties, and the denial of access to higher education and employment.[238][239][240]

The government has not released statistics regarding irreligiosity. However, the irreligious figures are growing and are higher in the diaspora, notably among Iranian Americans.[241][242]

-

Cube of Zoroaster

-

Saint Thaddeus Monastery

Culture

As the first sentence of Richard Nelson Frye's Greater Iran reads, "Iran's prize possession has been its culture."[243]

Persian culture has long been a predominant culture of the region, with Persian considered the language of intellectuals during much of the 2nd millennium, and the language of religion and the populace before that.

The Sassanid era was an important and influential historical period in Iran as Iranian culture influenced China, India and Roman civilization considerably,[244] and so influenced as far as Western Europe and Africa.[245]

This influence played a prominent role in the formation of both Asiatic and European medieval art.[246] This influence carried forward to the Islamic world. Much of what later became known as Islamic learning, such as philology, literature, jurisprudence, philosophy, medicine, architecture and the sciences were based on some of the practises taken from the Sassanid Persians.[247][248][249]

Art

Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and encompasses many disciplines including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and stonemasonry. There is also a very vibrant Iranian modern and contemporary art scene. The modern art movement in Iran had its genesis in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The 1949 opening of the Apadana gallery in Tehran by Mahmoud Javadipour and other colleagues, and the emergence of artists like Marcos Grigorian in the 1950s, signaled a commitment to the creation of a form of modern art grounded in Iran.[250]

Carpet-weaving is undoubtedly one of the most distinguished manifestations of Persian culture and art, and dates back to ancient Persia and the Bronze Age. Iran is the world's largest producer and exporter of handmade carpets, producing three quarters of the world's total output and having a share of 30% of world's export markets.[251][252]

Architecture

According to Persian historian and archaeologist Arthur Pope, the supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture. The supremacy of architecture applies to both pre-and post-Islamic periods.[253] The history of architecture of Iran goes back to the seventh millennium BC.

Iranian architecture generally displays great variety, both structural and aesthetic, developing gradually and coherently out of earlier traditions and experience. Without sudden innovations, and despite the repeated trauma of invasions and cultural shocks, it has achieved "an individuality distinct from that of other Muslim countries".[254] Its paramount virtues are several: "a marked feeling for form and scale; structural inventiveness, especially in vault and dome construction; a genius for decoration with a freedom and success not rivaled in any other architecture".[255]

Persians were among the first to use mathematics, geometry, and astronomy in architecture and also have extraordinary skills in making massive domes which can be seen frequently in the structure of bazaars and mosques. This greatly inspired the architecture of Iran's neighbors as well. The main building types of classical Iranian architecture are the mosque and the palace. Besides being home to a large number of art houses and galleries, Iran also holds one of the largest and most valuable jewel collections in the world. Iran ranks seventh among countries in the world with the most archeological architectural ruins and attractions from antiquity as recognized by UNESCO.[256] Fifteen of UNESCO's World Heritage Sites are creations of Iranian architecture.

-

The ruins of Persepolis

-

Shapour Xawst Castle in Khorram Abad City

-

The Dome of Soltaniyeh

-

Ahmad Shah Qajar's Pavilion in Niavaran Palace Complex

-

Entrance gate to the Shah Mosque in Isfahan

-

The Azadi Tower in Tehran

Literature

Persian literature is one of the world's oldest literatures. It dates back to the poetry of Avesta, about 1000 years BC. These poems which were a part of the oral traditions of ancient Iran, were orally transferred, and later created parts of the Avesta’s book during the Sassanid era. Its sources have been within historical Persia where the Persian language has historically been the national language.

Persian literature inspired Goethe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and many others, and it has been often dubbed as a most worthy language to serve as a conduit for poetry. Dialects of Persian are sporadically spoken throughout the region from China to Syria to Russia, though mainly in the Iranian Plateau.[257][258]

Poetry is used in many Persian classical works, whether from literature, science, or metaphysics. Persian literature has been considered by such thinkers as Goethe as one of the four main bodies of world literature.[259]

The Persian language has produced a number of famous poets; however, only a few poets as Rumi and Omar Khayyám have surfaced among western popular readership, even though the likes of Hafez, Saadi, Nizami,[260] Attar, Sanai, Nasir Khusraw and Jami are considered by many Iranians to be just as influential.

Philosophy

Iranian philosophy can be traced back as far as to Old Iranian philosophical traditions and thoughts which originated in ancient Indo-Iranian roots and were considerably influenced by Zarathustra's teachings. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, the chronology of the subject and science of philosophy starts with the Indo-Iranians, dating this event to 1500 BC. The Oxford dictionary also states, "Zarathushtra's philosophy entered to influence Western tradition through Judaism, and therefore on Middle Platonism."

Throughout Iranian history and due to remarkable political and social changes such as the Arab and Mongol invasions of Persia, a wide spectrum of schools of thoughts showed a variety of views on philosophical questions extending from Old Iranian and mainly Zoroastrianism-related traditions, to schools appearing in the late pre-Islamic era such as Manicheism and Mazdakism as well as various post-Islamic schools.

Iranian philosophy after the Muslim conquest of Persia, is characterized by different interactions with the Old Iranian philosophy, the Greek philosophy and with the development of Islamic philosophy. The Illumination School and the Transcendent Philosophy are regarded as two of the main philosophical traditions of that era in Persia.

Mythology

Persian mythology are traditional tales and stories of ancient origin, all involving extraordinary or supernatural beings. Drawn from the legendary past of Iran, they reflect the attitudes of the society to which they first belonged - attitudes towards the confrontation of good and evil, the actions of the gods, yazats (lesser gods), and the exploits of heroes and fabulous creatures.

Myths play a crucial part in Iranian culture and understanding of them is increased when they are considered within the context of Iranian history. For this purpose we must ignore modern political boundaries and look at historical developments in the Greater Iran, a vast area covering the Caucasus, and Central Asia, beyond the frontiers of present-day Iran. The geography of this region, with its high mountain ranges, plays a significant role in many of the mythological stories. The 2nd millennium BC is usually regarded as the age of migration because of the emergence in western Iran of a new form of Iranian pottery, similar to earlier wares of north-eastern Iran, suggesting the arrival of the Ancient Iranian peoples. This pottery, light grey to black in colour, appeared around 1400 BC. It is called Early Grey Ware or Iron I, the latter name indicating the beginning of the Iron Age in this area.[261]

The central collection of Persian mythology is the Shahnameh of Ferdowsi, written over a thousand years ago. Ferdowsi's work draws heavily, with attribution, on the stories and characters of Mazdaism and Zoroastrianism, not only from the Avesta, but from later texts such as the Bundahishn and the Denkard as well as many others.

Theater

Theater background in Persia goes back to antiquity (641–1000 BC).

The first initiation of theater and phenomena of acting in people of the land could be traced in the ceremonial theaters which were performed to glorify the heroes and humiliate the enemies, like Soug e Sivash or Mogh Koshi (Megakhouni), and also dances and theater narrations, and the musical history of mythological and love stories reported by Herodotos and Xenophon.

There were many dramatic performance arts popular before the advent of cinema in Persia. A few examples include Kheyme Shab Bazi (Puppetry), Saye Bazi (Shadow play), Rouhozi (Comical acts) and Tazieh (Martyr plays).

Rostam o Sohrab is an example of the opera performances in the modern day Iran.

Music

Iranian music, as evidenced by the archeological records of Elam in southwestern Iran, dates back thousands of years. In ancient Iran musicians held socially respectable positions. The Elamites and the Achaemenids certainly made use of musicians.

The history of the musical performance in Sassanid Iran is, however, better documented than earlier periods. This is specially more evident in the context of Zoroastrian ritual.[262] By the time of Xusro Parviz the Sassanid royal court was the host of prominent musicians such as Ramtin, Bamshad, Nakisa, Azad, Sarkash, and Barbad.

Like most of the world’s cultures, the music of Persia has depended on oral transmission and learning.[263]

Persian symphonic music has a long history. In fact Opera originated from Persia, much before its emergence in Europe. Iranians traditionally performed Tazieh, which in many respects resembles the European Opera.[264] Iran's main orchestra include National Orchestra, Tehran Symphony Orchestra, and Nations Orchestra.

Today the musical culture of Persia, while distinct, is closely related to other musical systems of the West and Central Asia. It has also affinities to the music cultures of the Indian subcontinent, to a certain degree even to those of Africa, and in the period after 1850 particularly, to that of Europe. Its history can be traced to some extent through these relationships.

Some Iranian traditional music instruments include Tar, Dotar, Setar, Kamanche, Harp, Barbat, Santur, Tanbur, Qanun, Dap, Dhol, Tompak (Goblet drum), and Ney.

Cinema and animation

The earliest examples of visual representations in Iranian history may be traced back to the bas-reliefs in Persepolis (c. 500 BC). Persepolis was the ritual center of the ancient kingdom of Achaemenids and the figures at Persepolis remain bound by the rules of grammar and syntax of visual language.[265] During the Sasanian reign, Iranian visual arts reached a pinnacle. A bas-relief from this period in Taq e Bostan depicts a complex hunting scene. Similar works from the period have been found to articulate movements and actions in a highly sophisticated manner. It is even possible to see a progenitor of the cinema close-up in one of these works of art, which shows a wounded wild pig escaping from the hunting ground.[266]

In the early 20th century, five-year-old industry of cinema came to Iran. The first Iranian filmmaker was Mirza Ebrahim Khan (Akkas Bashi), the official photographer of Mozaffar al Din Shah of Qajar. He obtained a camera and filmed the Shah's visit to Europe, upon the Shah's orders.

In 1904, Mirza Ebrahim Khan (Sahhaf Bashi) opened the first movie theater in Tehran.[267] After him, several others like Russi Khan, Ardeshir Khan, and Ali Vakili tried to establish new movie theaters in Tehran. Until the early 1930s, there were little more than 15 theatres in Tehran and 11 in other provinces.[266]

The first silent Iranian film was made by Professor Ovanes Ohanian in 1930, and the first sounded one, Lor Girl, was made by Abd ol Hossein Sepanta in 1932.

The 1960s was a significant decade for Iranian cinema, with 25 commercial films produced annually on average throughout the early 60s, increasing to 65 by the end of the decade. The majority of production focused on melodrama and thrillers. With the screening of the films Kaiser and The Cow, directed by Masoud Kimiai and Dariush Mehrjui respectively in 1969, alternative films established their status in the film industry. Attempts to organize a film festival that had begun in 1954 within the framework of the Golrizan Festival, bore fruits in the form of the Sepas Festival in 1969. The endeavors also resulted in the formation of the Tehran World Festival in 1973.

After the Revolution of 1979, as the new government imposed new laws and standards, a new age in Iranian cinema emerged, starting with Viva... by Khosrow Sinai and followed by many other Iranian directors who emerged in the last few decades, such as Abbas Kiarostami and Jafar Panahi. Kiarostami, who some critics regard as one of the few great directors in the history of Iranian cinema,[268] planted Iran firmly on the map of world cinema when he won the Palme d'Or for Taste of Cherry in 1997. The continuous presence of Iranian films in prestigious international festivals, such as the Cannes Film Festival, the Venice Film Festival, and the Berlin Film Festival, attracted world attention to Iranian masterpieces.[269] In 2006, six Iranian films, of six different styles, represented Iranian cinema at the Berlin Film Festival. Critics considered this a remarkable event in the history of Iranian cinema.[270][271]

Asghar Farhadi, a well-known Iranian director, has received a Golden Globe Award and an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, and was named as one of the 100 Most Influential People in the world by Time Magazine in 2012.

Other well-known Iranian directors include Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Majid Majidi, Bahram Beyzai, Bahman Ghobadi, Rakhshan Bani-E'temad, Amir Naderi, Ali Hatami and Reza Mirkarimi.

Marjane Satrapi, Shohreh Aghdashloo, Nazanin Boniadi, Shirin Neshat, Amir Mokri, Bahar Soomekh, Amir Talai, Nasim Pedrad, Daryush Shokof, and Rosie Malek-Yonan are among cinema people in the Iranian diaspora.

The oldest records of animation in Iran date back to the late half of 3rd millennium BC. An earthen goblet discovered at the site of the 5,200-year-old Burnt City in southeastern Iran, depicts what could possibly be the world’s oldest example of animation. The artifact bears five sequential images depicting a Persian Desert Ibex jumping up to eat the leaves of a tree.[272][273]

The art of animation, as practiced in modern day Iran, started in the 1950s. After four decades of animation production in Iran and three-decade experience of Kanoon Institute, Tehran International Animation Festival (TIAF) was established in February 1999. Every two years, participants from more than 70 countries attend this event which holds the biggest national animation market in Tehran.[274][275]

Sports

With two thirds of Iran's population under the age of 25, many sports are played in Iran, both traditional and modern.

Iran is the birthplace of polo,[276] (Naqsh-i Jahan Square in Isfahan is a polo field which was built by king Abbas I in the 17th century.) and Varzesh-e Pahlavani. Freestyle wrestling has been traditionally regarded as Iran's national sport. Iranian wrestling, known as koshti in Persian, has been practiced since ancient times throughout Iran. Iran's national wrestling team have been Olympic and world champion. The most popular sport in Iran is football with the national team having won the Asian Cup on three occasions. Basketball is also very popular in Iran where the national team won three of the last four Asian Championships.[277] In 1974, Iran became the first country in West Asia to host the Asian Games.

Iran is home to several unique skiing resorts.[278] 13 ski resorts operate in Iran,[279] the most famous being Tochal, Dizin, and Shemshak. All are within one to three hours traveling time of Tehran. Tochal resort is the world's fifth-highest ski resort (3,730 m or 12,238 ft at its highest station). Being a mountainous country, Iran is a venue for hiking, rock climbing,[280] and mountain climbing.[281][282]

Among the most popular athletes in the country are Hossein Rezazadeh and Behdad Salimi. Volleyball is Iran's second most popular sport in recent years. Men's National Team ranked fourth in 2014 FIVB Volleyball World League, ranked six in 2014 FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championship and the best result an Asian nation ever achieved.[283]

Holidays and festivals

Iran has three official calendar systems, including the Persian calendar as the main and national calendar, the Gregorian calendar for international events and Christian holidays, and the Lunar calendar for Islamic holidays.

Nowruz is the main national holiday of Iran, and is an ancient tradition celebrated on 21 March to mark the beginning of the spring. It is a secular holiday, enjoyed by people of different faiths; however, it is a holy day for Zoroastrians. It was registered on the list of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity,[284] and described as the Persian New Year[285][286][287][288] by UNESCO in 2009.

Some other national festivals of Iran include:

- Cha'r Shanbe Suri: A prelude to Nowruz, in honor of Atar (the Holy Fire) – It is celebrated by fire-jumping and fireworks, on the last Wednesday before Nowruz.

- Sizda' be Dar: Leaving the house and joining the nature, on the thirteenth day of the Persian new year (April 2) – It is followed by the Nowruz holidays.

- Chelle: Also known as Yalda – It is the longest night of the year, on the eve of Winter Solstice, and is celebrated by reading poetical horoscopes (commonly the poems of Hafez) and having the traditional fruits of this night which include watermelon, pomegranate and nuts.

- Tirgan: Celebrated on the thirteenth day of Tir (July 4), in honor of Tishtrya

- Mehrgan: Celebrated on the sixteenth day of Mehr (October 8), in honor of Mithra