Intersection number

In mathematics, and especially in algebraic geometry, the intersection number generalizes the intuitive notion of counting the number of times two curves intersect to higher dimensions, multiple (more than 2) curves, and accounting properly for tangency. One needs a definition of intersection number in order to state results like Bézout's theorem.

The intersection number is obvious in certain cases, such as the intersection of x- and y-axes which should be one. The complexity enters when calculating intersections at points of tangency and intersections along positive dimensional sets. For example if a plane is tangent to a surface along a line, the intersection number along the line should be at least two. These questions are discussed systematically in intersection theory.

Definition for Riemann surfaces

Let X be a Riemann surface. Then the intersection number of two closed curves on X has a simple definition in terms of an integral. For every closed curve c on X (i.e., smooth function  ), we can associate a differential form

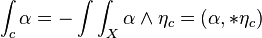

), we can associate a differential form  with the pleasant property that integrals along c can be calculated by integrals over X:

with the pleasant property that integrals along c can be calculated by integrals over X:

, for every closed (1-)differential

, for every closed (1-)differential  on X,

on X,

where  is the wedge product of differentials, and

is the wedge product of differentials, and  is the hodge star. Then the intersection number of two closed curves, a and b, on X is defined as

is the hodge star. Then the intersection number of two closed curves, a and b, on X is defined as

.

.

The  have an intuitive definition as follows. They are a sort of dirac delta along the curve c, accomplished by taking the differential of a unit step function that drops from 1 to 0 across c. More formally, we begin by defining for a simple closed curve c on X, a function fc by letting

have an intuitive definition as follows. They are a sort of dirac delta along the curve c, accomplished by taking the differential of a unit step function that drops from 1 to 0 across c. More formally, we begin by defining for a simple closed curve c on X, a function fc by letting  be a small strip around c in the shape of an annulus. Name the left and right parts of

be a small strip around c in the shape of an annulus. Name the left and right parts of  as

as  and

and  . Then take a smaller sub-strip around c,

. Then take a smaller sub-strip around c,  , with left and right parts

, with left and right parts  and

and  . Then define fc by

. Then define fc by

.

.

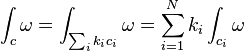

The definition is then expanded to arbitrary closed curves. Every closed curve c on X is homologous to  for some simple closed curves ci, that is,

for some simple closed curves ci, that is,

, for every differential

, for every differential  .

.

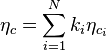

Define the  by

by

.

.

Definition for algebraic varieties

The usual constructive definition in the case of algebraic varieties proceeds in steps. The definition given below is for the intersection number of divisors on a nonsingular variety X.

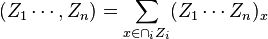

1. The only intersection number that can be calculated directly from the definition is the intersection of hypersurfaces (subvarieties of X of codimension one) that are in general position at x. Specifically, assume we have a nonsingular variety X, and n hypersurfaces Z1, ..., Zn which have local equations f1, ..., fn near x for polynomials fi(t1, ..., tn), such that the following hold:

-

.

. -

for all i. (i.e., x is in the intersection of the hypersurfaces.)

for all i. (i.e., x is in the intersection of the hypersurfaces.) -

(i.e., the divisors are in general position.)

(i.e., the divisors are in general position.) - The

are nonsingular at x.

are nonsingular at x.

Then the intersection number at the point x is

,

,

where  is the local ring of X at x, and the dimension is dimension as a k-vector space. It can be calculated as the localization

is the local ring of X at x, and the dimension is dimension as a k-vector space. It can be calculated as the localization ![k[U]_{\mathfrak{m}_x}](../I/m/5a26a1297917498190747662c6399269.png) , where

, where  is the maximal ideal of polynomials vanishing at x, and U is an open affine set containing x and containing none of the singularities of the fi.

is the maximal ideal of polynomials vanishing at x, and U is an open affine set containing x and containing none of the singularities of the fi.

2. The intersection number of hypersurfaces in general position is then defined as the sum of the intersection numbers at each point of intersection.

3. Extend the definition to effective divisors by linearity, i.e.,

and

and  .

.

4. Extend the definition to arbitrary divisors in general position by noticing every divisor has a unique expression as D = P - N for some effective divisors P and N. So let Di = Pi - Ni, and use rules of the form

to transform the intersection.

5. The intersection number of arbitrary divisors is then defined using a "Chow's moving lemma" that guarantees we can find linearly equivalent divisors that are in general position, which we can then intersect.

Note that the definition of the intersection number does not depend on the order of the divisors.

Further definitions

The definition can be vastly generalized, for example to intersections along subvarieties instead of just at points, or to arbitrary complete varieties.

In algebraic topology, the intersection number appears as the Poincaré dual of the cup product. Specifically, if two manifolds, X and Y, intersect transversely in a manifold M, the homology class of the intersection is the Poincaré dual of the cup product  of the Poincaré duals of X and Y.

of the Poincaré duals of X and Y.

Intersection multiplicities for plane curves

There is a unique function assigning to each triplet (P, Q, p) consisting of a pair of polynomials, P and Q, in K[x, y] and a point p in K2 a number Ip(P, Q) called the intersection multiplicity of P and Q at p that satisfies the following properties:

-

-

is infinite if and only if P and Q have a common factor that is zero at p.

is infinite if and only if P and Q have a common factor that is zero at p. -

is zero if and only if one of P(p) or Q(p) is non-zero (i.e. the point p is off one of the curves).

is zero if and only if one of P(p) or Q(p) is non-zero (i.e. the point p is off one of the curves). -

where the point p is at (x, y).

where the point p is at (x, y). -

-

for any R in K[x, y]

for any R in K[x, y]

Although these properties completely characterize intersection multiplicity, in practice it is realised in several different ways.

One realization of intersection multiplicity is through the dimension of a certain quotient space of the power series ring K[[x,y]]. By making a change of variables if necessary, we may assume that the point p is (0,0). Let P(x, y) and Q(x, y) be the polynomials defining the algebraic curves we are interested in. If the original equations are given in homogeneous form, these can be obtained by setting z = 1. Let I = (P, Q) denote the ideal of K[[x,y]] generated by P and Q. The intersection multiplicity is the dimension of K[[x, y]]/I as a vector space over K.

Another realization of intersection multiplicity comes from the resultant of the two polynomials P and Q. In coordinates where p is (0,0), the curves have no other intersections with y = 0, and the degree of P with respect to x is equal to the total degree of P, Ip(P, Q) can be defined as the highest power of y that divides the resultant of P and Q (with P and Q seen as polynomials over K[x]).

Intersection multiplicity can also be realised as the number of distinct intersections that exist if the curves are perturbed slightly. More specifically, if P and Q define curves which intersect only once in the closure of an open set U, then for a dense set of (ε,δ) in K2, P − ε and Q − δ are smooth and intersect transversally (i.e. have different tangent lines) at exactly some number n points in U. Ip(P, Q) = n.

Example

Consider the intersection of the x-axis with the parabola

Then

and

so

Thus, the intersection degree is two; it is an ordinary tangency.

Self-intersections

Some of the most interesting intersection numbers to compute are self-intersection numbers. This should not be taken in a naive sense. What is meant is that, in an equivalence class of divisors of some specific kind, two representatives are intersected that are in general position with respect to each other. In this way, self-intersection numbers can become well-defined, and even negative.

Applications

The intersection number is partly motivated by the desire to define intersection to satisfy Bézout's theorem.

The intersection number arises in the study fixed points, which can be cleverly defined as intersections of function graphs with a diagonals. Calculating the intersection numbers at the fixed points counts the fixed points with multiplicity, and leads to the Lefschetz fixed point theorem in quantitative form.

References

- William Fulton (1974). Algebraic Curves. Mathematics Lecture Note Series. W.A. Benjamin. pp. 74–83. ISBN 0-8053-3082-8.

- Robin Hartshorne (1977). Algebraic Geometry. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 52. ISBN 0-387-90244-9. Appendix A.

- William Fulton (1998). Intersection Theory (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 9780387985497.

- Algebraic Curves: An Introduction To Algebraic Geometry, by William Fulton with Richard Weiss. New York: Benjamin, 1969. Reprint ed.: Redwood City, CA, USA: Addison-Wesley, Advanced Book Classics, 1989. ISBN 0-201-51010-3. Full text online.

- Irwin Kra (1980). Riemann Surfaces. Graduate Texts in Mathematics 71. ISBN 0-387-90465-4.