Integrated farming

’’’Integrated Farming’’’ (IF) is a whole farm management system which aims to deliver more sustainable agriculture. It is a dynamic approach which can be applied to any farming system around the world. It involves attention to detail and continuous improvement in all areas of a farming business through informed management processes. Integrated Farming combines the best of modern tools and technologies with traditional practices according to a given site and situation.

Definition

The International Organisation of Biological Control (IOBC) describes Integrated Farming as a farming system where high quality food, feed, fibre and renewable energy are produced by using resources such as soil, water, air and nature as well as regulating factors to farm sustainably and with as little polluting inputs as possible.[1]

Particular emphasis is placed on a holistic management approach looking at the whole farm as cross-linked unit, on the fundamental role and function of agro-ecosystems, on nutrient cycles which are balanced and adapted to the demand of the crops, and on health and welfare of all livestock on the farm. Preserving and enhancing soil fertility, maintaining and improving a diverse environment and the adherence to ethical and social criteria are indispensable basic elements. Crop protection takes into account all biological, technical and chemical methods which then are balanced carefully and with the objective to protect the environment, to maintain profitability of the business and fulfil social requirements.[2]

EISA European Initiative for Sustainable Development in Agriculture e. V. have an Integrated Farming Framework[3] which provides additional explanations on key aspects of Integrated Farming. These include: Organisation & Planning, Human & Social Capital, Energy Efficiency, Water Use & Protection, Climate Change & Air Quality, Soil Management, Crop Nutrition, Crop Health & Protection, Animal Husbandry, Health & Welfare, Landscape & Nature Conservation and Waste Management Pollution Control.

LEAF (Linking Environment and Farming) official website in the UK promotes a comparable model and defines Integrated Farm Management (IFM) as whole farm business approach that delivers sustainable farming.[4]

Classification

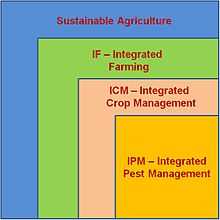

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FAO promotes Integrated Pest Management (IPM) as the preferred approach to crop protection and regards it as a pillar of both sustainable intensification of crop production and pesticide risk reduction”.[5] IPM thus is one indispensable element of Integrated Crop Management which in turn is one essential part of the holistic Integrated Farming approach towards sustainable agriculture.

KELLER, 1985 (quoted in Lütke Entrup et al., 1998 1) highlights that Integrated Crop Management is not to be understood as compromise between different agricultural production systems. It rather must be understood as production system with a targeted, dynamic and continuous use and development of experiences which were made in the so-called conventional farming. In addition to natural scientific findings, impulses from organic farming are also taken up.

History

Integrated Pest Management can be seen as starting point for an holistic approach to agricultural production. Following the excessive use of crop protection chemicals, first steps in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) were taken in fruit production at the end of the [19]50s. The concept was then further developed globally in all major crops. On the basis of results of the system-oriented IPM approach, models for Integrated Crop Management were developed. Initially, animal husbandry was not seen as part of such integrated approaches (Lütke Entrup et al., 1998 1).

In the years to follow, various national and regional initiatives and projects were formed. These include LEAF (Linking Environment And Farming) in the UK, FNL (Fördergemeinschaft Nachhaltige Landwirtschaft e.V.) in Germany, FARRE (Forum des Agriculteurs Responsables Respectueux de l'Environnement) in France, FILL (Fördergemeinschaft Integrierte Landbewirtschaftung Luxemburg) or OiB (Odling i Balans) in Sweden. However, there are few if any figures on the uptake of Integrated Farming in the major crops throughout Europe for example, leading to a recommendation by the European Economic and Social Committee in February 2014, that the EU should carry out an in-depth analysis of integrated production in Europe in order to obtain insights into the current situation and potential developments.[6] There is evidence, however, that between 60 and 80% of pome, stone and soft fruits were grown, controlled and marketed according to “Integrated Production Guidelines” in 1999 already in Germany for example.[7] In the UK, 22% of fresh fruit and vegetables are grown to Integrated Farm Management standards as recognised by the LEAF Marque.[8]

Animal husbandry and Integrated Crop Management (ICM) often are just two branches of one agricultural enterprise. In modern agriculture, animal husbandry and crop production must ber understood as interlinked sectors which cannot be looked at in isolation, as the context of agricultural systems leads to tight interdependencies. Uncoupling animal husbandry from arable production (too high stocking rates) is therefore not considered in accordance with the principles and objectives of Integrated Farming (Lütke Entrup et al., 1998 1). Accordingly, holistic concepts for Integrated Farming or Integrated Farm Management such as the EISA Integrated Farming Framework,[9] and the concept of sustainable agriculture are increasingly developed, promoted and implemented on the global level.

Related to the ‘sustainable intensification’ of agriculture,[10] an objective which in part is discussed controversially, efficiency of resource use becomes increasingly important today. Environmental impacts of agricultural production depend on the efficiency achieved when using natural resources and all other means of production. The input per kg of output, the output per kg of input, and the output achieved per hectare of land – a limited resource in the light of world population growth – are decisive figures for evaluating the efficiency and the environmental impact of agricultural systems.[11] Efficiency parameters therefore offer important evidence how efficiency and environmental impacts of agriculture can be judged and where improvements can or must be made.

Against this background, documentation as well certification schemes and farm audits such as LEAF Marque[12] in the UK and 33 other countries throughout the world become more and more important tools to evaluate – and further improve – agricultural practices. Even though being by far more product- or sector-oriented, SAI Platform principles and practices[13] and GlobalGap[14] for example pursue similar approaches.

Objectives

Integrated Farming is based on attention to detail, continuous improvement and managing all resources available.[15]

Being bound to sustainable development, the underlying three dimensions “economic development”, “social development” and “environmental protection” are thoroughly considered in the practical implementation of Integrated Farming. However, the need for profitability is a decisive prerequisite: To be sustainable, the system must be profitable, as profits generate the possibility to support all activities outlined in the (EISA Integrated Farming) IF Framework.[16]

As a management and planning approach, Integrated Farming includes regular benchmarking of targets set against results achieved. The concept of the EISA Integrated Farming Framework for example has a clear focus on farmers’ awareness of their own performance. By regularly benchmarking their performance, farmers become aware of achievements as well as deficiencies, and by y paying attention to detail they can continuously work on improving the whole farming enterprise and their economic performance at the same time: According to findings in the UK, reducing fertiliser and chemical inputs to amounts according to the demand of the crops allowed for cost savings in the range of £2,500 - £10,000 per year and per farm.[17]

Prevalence

Following first developments in the [19]50s, various approaches to Integrated Pest Management, Integrated Crop Management, Integrated Production and Integrated Farming were developed worldwide (in Germany, Switzerland, US, Australia, and India, for example).[18][19][20][21][22] As the implementation of the general concept of Integrated Farming and its individual components always should be handled according to the given site and situation instead of following strict rules and recipes, the concept is virtually applicable – and being used to various degrees – all over the world.

Criticism

It should be mentioned, however, that there are also critical voices from environmental organisations for example. That is in part due to the fact that there are European Organic Regulations such as (EC) No 834/2007[23] or the new draft from 2014[24] but no comparable regulations for Integrated Farming. Whereas organic farming and the “Bio-Siegel” in Germany for example are legally protected, EU Commission has not yet considered to start working on a comparable framework or blueprint for Integrated Farming. When products are marketed as “Controlled Integrated Produce”, according control mechanisms and quality-labels are not based on national or European directives but are established and handled by private organisations and quality schemes such as LEAF Marque for example.[25]

See also

- Integrated Production

Additional reading

- Lütke Entrup, N., Onnen, O., and Teichgräber, B., 1998: Zukunftsfähige Landwirtschaft – Integrierter Landbau in Deutschland und Europa – Studie zur Entwicklung und den Perspektiven. Heft 14/1998, Fördergemeinschaft Integrierter Pflanzenbau, Bonn. ISBN 3-926898-13-5. (Available in German only)

- Oerke, E.-C., Dehne, H.-W., Schönbeck, F., and Weber, A., 1994: Crop Production and Crop Protection – Estimated Losses in Major Food and Cash Crops. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Lausanne, New York, Oxford, Shannon, Tokyo. ISBN 0-444-82095-7

References

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ Stand 25. Juli 2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 21.08.2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 05.09.2014

- ↑ as of 05.09.2014

- ↑ LEAFmarquecertification/whatis.eb LEAF’s Sustainability Report, page 10, as of 21.08.2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 05.09.2014

- ↑ of 08.10.2014

- ↑ LEAFmarquecertification/whatis.eb LEAF’s Sustainability Report, page 10, as of 21.08.2014

- ↑ as of 28.07.2014

- ↑ as of 28.07.2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 28.07.2014

- ↑ as of 05.09.2014

- ↑ as of 28.07.2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 25.07.2014

- ↑ as of 21.08.2014

- ↑ as of 28.07.2014

- ↑ as of 22.08.2014

- ↑ LEAFmarquecertification/whatis.eb LEAF’S Sustainability Report, page 10, as of 21.08.2014