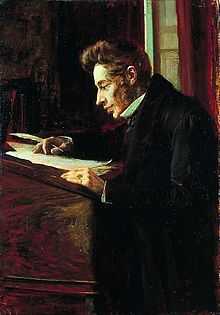

Influence and reception of Søren Kierkegaard

Søren Kierkegaard's influence and reception varied widely and may be roughly divided into various chronological periods. Reactions were anything but uniform, and proponents of various ideologies attempted to appropriate his work quite early.

Kierkegaard's reputation as a philosopher was first established in his native Denmark with his work Either/Or.[1] Henriette Wulff, in a letter to Hans Christian Andersen, wrote, "Recently a book was published here with the title Either/Or! It is supposed to be quite strange, the first part full of Don Juanism, skepticism, et cetera, and the second part toned down and conciliating, ending with a sermon that is said to be quite excellent. The whole book attracted much attention. It has not yet been discussed publicly by anyone, but it surely will be. It is actually supposed to be by a Kierkegaard who has adopted a pseudonym...."[1]

Kierkegaard's fame in Denmark increased with each publication of his philosophical works, including Fear and Trembling and Philosophical Fragments, and culminating in his magnum opus, the Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments. However, Kierkegaard's attack upon Christendom, represented by the Danish National Church near the end of his life, did not endear him to many in the clergy and theological circles. After his death, his original manuscript were bequeathed by his one-time fiancee, Regine Olsen for prosperity. She later donated most of his writings to the Danish Royal Library where they continue to be stored.

Kierkegaard's thought gained a wider audience with the translation of his works into German, French, and English.

Kierkegaard and philosophy and theology

Many 20th-century philosophers, both theistic and atheistic, drew concepts from Kierkegaard, including the notions of angst, despair, and the importance of the individual. His fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, in large part because the ascendant existentialist movement pointed to him as a precursor, although later writers celebrated him as a highly significant and influential thinker in his own right.[2] Since Kierkegaard was raised as a Lutheran,[3] he was commemorated as a teacher in the Calendar of Saints of the Lutheran Church on 11 November and in the Calendar of Saints of the Episcopal Church with a feast day on 8 September.

Philosophers and theologians influenced by Kierkegaard include Hans Urs von Balthasar, Karl Barth, Simone de Beauvoir, Niels Bohr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Emil Brunner, Martin Buber, Rudolf Bultmann, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Reinhold Niebuhr, Franz Rosenzweig, Jean-Paul Sartre, Joseph Soloveitchik, Paul Tillich, Malcolm Muggeridge, Thomas Merton, Miguel de Unamuno.[4] Paul Feyerabend's epistemological anarchism in the philosophy of science was inspired by Kierkegaard's idea of subjectivity as truth. Ludwig Wittgenstein was immensely influenced and humbled by Kierkegaard,[5] claiming that "Kierkegaard is far too deep for me, anyhow. He bewilders me without working the good effects which he would in deeper souls".[5] Karl Popper referred to Kierkegaard as "the great reformer of Christian ethics, who exposed the official Christian morality of his day as anti-Christian and anti-humanitarian hypocrisy".[6]

Kierkegaard and psychology

Kierkegaard had a profound influence on psychology. He is widely regarded as the founder of Christian psychology and of existential psychology and therapy.[7] Existentialist (often called "humanistic") psychologists and therapists include Ludwig Binswanger, Viktor Frankl, Erich Fromm, Carl Rogers, and Rollo May. May based his The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety. Kierkegaard's sociological work Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age critiques modernity.[8] Ernest Becker based his 1974 Pulitzer Prize book, The Denial of Death, on the writings of Kierkegaard, Freud and Otto Rank. Kierkegaard is also seen as an important precursor of postmodernism.[9]

Kierkegaard and literature

Kierkegaard influenced 19th-century literature writers as well as 20th-century literature. August Strindberg (1843-1912) found inspiration in Kierkegaard and the famous Norwegian dramatist and poet Henrik Ibsen (1828-1906) clearly seems to have been inspired by the Dane in famous works such as Brand. The other great Norwegian national writer and poet Bjornstjerne Bjornson (1832-1910) was also deeply inspired by Kierkegaard.[10] Finally the celebrated Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (17863-1944) closely studied key concepts such as anxiety, and this influence is notable in some of his iconic paintings such as The Scream.[11]

Other figures deeply influenced by his work include W. H. Auden, Jorge Luis Borges, Don DeLillo, Hermann Hesse, Franz Kafka,[12] David Lodge, Flannery O'Connor, Walker Percy, Rainer Maria Rilke, J.D. Salinger and John Updike.[13] Kierkegaard's work The Diary of a Seducer has been re-published several times, including Princeton University Press' translation with John Updike's foreword and Penguin Books' series Great Loves.

20th-century thinkers

Philosophers and theologians influenced by Kierkegaard include Hans Urs von Balthasar, Karl Barth, Simone de Beauvoir, Niels Bohr, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Emil Brunner, Martin Buber, Rudolf Bultmann, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Karl Jaspers, Gabriel Marcel, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Reinhold Niebuhr, Franz Rosenzweig, Jean-Paul Sartre, Joseph Soloveitchik, Paul Tillich, Malcolm Muggeridge, Thomas Merton, Miguel de Unamuno.[4] Paul Feyerabend's epistemological anarchism in the philosophy of science was inspired by Kierkegaard's idea of subjectivity as truth. Sir Karl Popper, in his work The Open Society and its Enemies referred to Kierkegaard as "the great reformer of Christian ethics, who exposed the official Christian morality of his day as anti-Christian and anti-humanitarian hypocrisy".[6]

Kierkegaard after World War I

Kierkegaard's present stature in the English-speaking world owes much to the exegetical writings and improved Kierkegaard translations by the American theologian Walter Lowrie, the University of Minnesota philosopher David F. Swenson, and the Danish translators Howard and Edna Hong. Anthony Rudd's book Kierkegaard and the Limits of the Ethical and Alasdair MacIntyre's discussion of Kierkegaard in After Virtue and A Short History of Ethics did much to facilitate Kierkegaard's legacy in ethical thought in analytic philosophy.

Kierkegaard's influence on continental philosophy increased dramatically after the First and Second World Wars, especially among the German existenz thinkers and French existentialists. Jean-Paul Sartre, Emmanuel Levinas, and Karl Barth all owe a heavy debt to Kierkegaard. Paul Ricoeur and Judith Butler wrote monographs drawing new attention to Kierkegaard's work, and a 1964 UNESCO colloquium on Kierkegaard in Paris ranks as one of the most important events for a generation's reception of Kierkegaard, which included a keynote speaker, Sartre who gave his lecture The Singular Universal, which solidified Kierkegaard's influence over existentialism.[14] In America, interest in Kierkegaard was revived from the 1980s onwards, particularly by the American philosopher and curator of the Kierkegaard Library at St. Olaf College Gordon Marino, who has devoted several books and essays to Kierkegaard. In Kierkegaard's native Denmark, the Danish people hosted his 200th anniversary of Kierkegaard's birth in Copenhagen in May 2013.[15]

Kierkegaard has also influenced members of the analytical philosophy tradition, most notably Ludwig Wittgenstein, who considered Kierkegaard to be "the most profound thinker of the [nineteenth] century. Kierkegaard was a saint."[16]

Kierkegaard predicted his posthumous fame, and foresaw that his work would become the subject of intense study and research. In his journals, he wrote:

"What the age needs is not a genius—it has had geniuses enough, but a martyr, who in order to teach men to obey would himself be obedient unto death. What the age needs is awakening. And therefore someday, not only my writings but my whole life, all the intriguing mystery of the machine will be studied and studied. I never forget how God helps me and it is therefore my last wish that everything may be to his honour."[17]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Garff, Joakim. Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography. Trans. Bruce H. Kirmmse. Princeton, 2005, 0-691-09165-X

- ↑ Weston 1994

- ↑ Hampson 2001

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Unamuno refers to Kierkegaard in his book The Tragic Sense of Life, Part IV, "In The Depths of the Abyss"

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Creegan 1989

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Popper 2002

- ↑ Ostenfeld & McKinnon 1972

- ↑ Kierkegaard 2001

- ↑ Matustik & Westphal 1995

- ↑ See In God's Way, by Bjornson In God's Way. Bjornson names one of his characters Soren Pedersen. Kierkegaard's father's name was Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard.

- ↑ Kierkegaard's Influence on Literature, Criticism and Art: The Germanophone World Feb 28, 2013, by Jon Stewart p. xii

- ↑ McGee 2006

- ↑ Updike 1997

- ↑ Matuštík, M. (1995), Kierkegaard in Post/Modernity, Indiana University Press, p. 18.

- ↑ Kierkegaard in 2013

- ↑ Notes on Wittgenstein's Reading of Kierkegaard by Jens Glebe-Moeller.

- ↑ Dru 1938, p. 224

References

- Creegan, Charles (1989). "Wittgenstein and Kierkegaard". Routledge. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- Dru, Alexander (1938). The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hampson, Daphne (2001). Christian Contradictions: The Structures of Lutheran and Catholic Thought. Cambridge.

- Popper, Sir Karl R (2002). The Open Society and Its Enemies Vol 2: Hegel and Marx. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29063-5.

- Weston, Michael (1994). Kierkegaard and Modern Continental Philosophy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10120-4.

- McGee, Kyle. "Fear and Trembling in the Penal Colony". Kafka Project. Retrieved 2013-04-26.