Inequality (mathematics)

- Not to be confused with Inequation. "Less than", "Greater than", and "More than" redirect here. For the use of the "<" and ">" signs as punctuation, see Bracket. For the UK insurance brand "More Th>n", see RSA Insurance Group.

In mathematics, an inequality is a relation that holds between two values when they are different (see also: equality).

- The notation a ≠ b means that a is not equal to b.

It does not say that one is greater than the other, or even that they can be compared in size.

If the values in question are elements of an ordered set, such as the integers or the real numbers, they can be compared in size.

- The notation a < b means that a is less than b.

- The notation a > b means that a is greater than b.

In either case, a is not equal to b. These relations are known as strict inequalities. The notation a < b may also be read as "a is strictly less than b".

In contrast to strict inequalities, there are two types of inequality relations that are not strict:

- The notation a ≤ b means that a is less than or equal to b (or, equivalently, not greater than b, or at most b).

- The notation a ≥ b means that a is greater than or equal to b (or, equivalently, not less than b, or at least b).

An additional use of the notation is to show that one quantity is much greater than another, normally by several orders of magnitude.

- The notation a ≪ b means that a is much less than b. (In measure theory, however, this notation is used for absolute continuity, an unrelated concept.)

- The notation a ≫ b means that a is much greater than b.

Properties

Inequalities are governed by the following properties. All of these properties also hold if all of the non-strict inequalities (≤ and ≥) are replaced by their corresponding strict inequalities (< and >) and (in the case of applying a function) monotonic functions are limited to strictly monotonic functions.

Transitivity

The transitive property of inequality states:

- For any real numbers a, b, c:

- If a ≥ b and b ≥ c, then a ≥ c.

- If a ≤ b and b ≤ c, then a ≤ c.

- If either of the premises is a strict inequality, then the conclusion is a strict inequality.

- E.g. if a ≥ b and b > c, then a > c

- An equality is of course a special case of a non-strict inequality.

- E.g. if a = b and b > c, then a > c

Converse

The relations ≤ and ≥ are each other's converse:

- For any real numbers a and b:

- If a ≤ b, then b ≥ a.

- If a ≥ b, then b ≤ a.

Addition and subtraction

A common constant c may be added to or subtracted from both sides of an inequality:

- For any real numbers a, b, c

- If a ≤ b, then a + c ≤ b + c and a − c ≤ b − c.

- If a ≥ b, then a + c ≥ b + c and a − c ≥ b − c.

i.e., the real numbers are an ordered group under addition.

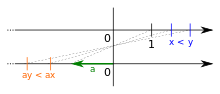

Multiplication and division

The properties that deal with multiplication and division state:

- For any real numbers, a, b and non-zero c:

- If c is positive, then multiplying or dividing by c does not change the inequality:

- If a ≥ b and c > 0, then ac ≥ bc and a/c ≥ b/c.

- If a ≤ b and c > 0, then ac ≤ bc and a/c ≤ b/c.

- If c is negative, then multiplying or dividing by c inverts the inequality:

- If a ≥ b and c < 0, then ac ≤ bc and a/c ≤ b/c.

- If a ≤ b and c < 0, then ac ≥ bc and a/c ≥ b/c.

- If c is positive, then multiplying or dividing by c does not change the inequality:

More generally, this applies for an ordered field, see below.

Additive inverse

The properties for the additive inverse state:

- For any real numbers a and b, negation inverts the inequality:

- If a ≤ b, then −a ≥ −b.

- If a ≥ b, then −a ≤ −b.

Multiplicative inverse

The properties for the multiplicative inverse state:

- For any non-zero real numbers a and b that are both positive or both negative:

- If a ≤ b, then 1/a ≥ 1/b.

- If a ≥ b, then 1/a ≤ 1/b.

- If one of a and b is positive and the other is negative, then:

- If a < b, then 1/a < 1/b.

- If a > b, then 1/a > 1/b.

These can also be written in chained notation as:

- For any non-zero real numbers a and b:

- If 0 < a ≤ b, then 1/a ≥ 1/b > 0.

- If a ≤ b < 0, then 0 > 1/a ≥ 1/b.

- If a < 0 < b, then 1/a < 0 < 1/b.

- If 0 > a ≥ b, then 1/a ≤ 1/b < 0.

- If a ≥ b > 0, then 0 < 1/a ≤ 1/b.

- If a > 0 > b, then 1/a > 0 > 1/b.

Applying a function to both sides

Any monotonically increasing function may be applied to both sides of an inequality (provided they are in the domain of that function) and it will still hold. Applying a monotonically decreasing function to both sides of an inequality means the opposite inequality now holds. The rules for the additive inverse, and the multiplicative inverse for positive numbers, are both examples of applying a monotonically decreasing function.

If the inequality is strict (a < b, a > b) and the function is strictly monotonic, then the inequality remains strict. If only one of these conditions is strict, then the resultant inequality is non-strict. The rules for additive and multiplicative inverses are both examples of applying a strictly monotonically decreasing function.

As an example, consider the application of the natural logarithm to both sides of an inequality when a and b are positive real numbers:

- a ≤ b ⇔ ln(a) ≤ ln(b).

- a < b ⇔ ln(a) < ln(b).

This is true because the natural logarithm is a strictly increasing function.

Ordered fields

If (F, +, ×) is a field and ≤ is a total order on F, then (F, +, ×, ≤) is called an ordered field if and only if:

- a ≤ b implies a + c ≤ b + c;

- 0 ≤ a and 0 ≤ b implies 0 ≤ a × b.

Note that both (Q, +, ×, ≤) and (R, +, ×, ≤) are ordered fields, but ≤ cannot be defined in order to make (C, +, ×, ≤) an ordered field, because −1 is the square of i and would therefore be positive.

The non-strict inequalities ≤ and ≥ on real numbers are total orders. The strict inequalities < and > on real numbers are strict total orders.

Chained notation

The notation a < b < c stands for "a < b and b < c", from which, by the transitivity property above, it also follows that a < c. Obviously, by the above laws, one can add/subtract the same number to all three terms, or multiply/divide all three terms by same nonzero number and reverse all inequalities according to sign. Hence, for example, a < b + e < c is equivalent to a − e < b < c − e.

This notation can be generalized to any number of terms: for instance, a1 ≤ a2 ≤ ... ≤ an means that ai ≤ ai+1 for i = 1, 2, ..., n − 1. By transitivity, this condition is equivalent to ai ≤ aj for any 1 ≤ i ≤ j ≤ n.

When solving inequalities using chained notation, it is possible and sometimes necessary to evaluate the terms independently. For instance to solve the inequality 4x < 2x + 1 ≤ 3x + 2, it is not possible to isolate x in any one part of the inequality through addition or subtraction. Instead, the inequalities must be solved independently, yielding x < 1/2 and x ≥ −1 respectively, which can be combined into the final solution −1 ≤ x < 1/2.

Occasionally, chained notation is used with inequalities in different directions, in which case the meaning is the logical conjunction of the inequalities between adjacent terms. For instance, a < b = c ≤ d means that a < b, b = c, and c ≤ d. This notation exists in a few programming languages such as Python.

Inequalities between means

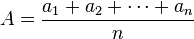

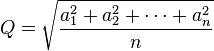

There are many inequalities between means. For example, for any positive numbers a1, a2, …, an we have H ≤ G ≤ A ≤ Q, where

(harmonic mean), ![G = \sqrt[n]{a_1 \cdot a_2 \cdots a_n}](../I/m/c4b2be327655964f6682cd4b090a3882.png)

(geometric mean),

(arithmetic mean),

(quadratic mean).

Power inequalities

A "power inequality" is an inequality containing ab terms, where a and b are real positive numbers or variable expressions. They often appear in mathematical olympiads exercises.

Examples

- For any real x,

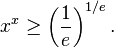

- If x > 0, then

- If x ≥ 1, then

- If x, y, z > 0, then

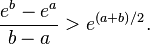

- For any real distinct numbers a and b,

- If x, y > 0 and 0 < p < 1, then

- If x, y, z > 0, then

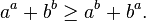

- If a, b > 0, then

-

- This inequality was solved by I.Ilani in JSTOR,AMM,Vol.97,No.1,1990.

- If a, b > 0, then

-

- This inequality was solved by S.Manyama in AJMAA,Vol.7,Issue 2,No.1,2010 and by V.Cirtoaje in JNSA,Vol.4,Issue 2,130-137,2011.

- If a, b, c > 0, then

- If a, b > 0, then

-

- This result was generalized by R. Ozols in 2002 who proved that if a1, ..., an > 0, then

-

- (result is published in Latvian popular-scientific quarterly The Starry Sky, see references).

Well-known inequalities

Mathematicians often use inequalities to bound quantities for which exact formulas cannot be computed easily. Some inequalities are used so often that they have names:

- Azuma's inequality

- Bernoulli's inequality

- Boole's inequality

- Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

- Chebyshev's inequality

- Chernoff's inequality

- Cramér–Rao inequality

- Hoeffding's inequality

- Hölder's inequality

- Inequality of arithmetic and geometric means

- Jensen's inequality

- Kolmogorov's inequality

- Markov's inequality

- Minkowski inequality

- Nesbitt's inequality

- Pedoe's inequality

- Poincaré inequality

- Samuelson's inequality

- Triangle inequality

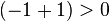

Complex numbers and inequalities

The set of complex numbers  with its operations of addition and multiplication is a field, but it is impossible to define any relation ≤ so that

with its operations of addition and multiplication is a field, but it is impossible to define any relation ≤ so that  becomes an ordered field. To make

becomes an ordered field. To make  an ordered field, it would have to satisfy the following two properties:

an ordered field, it would have to satisfy the following two properties:

- if a ≤ b then a + c ≤ b + c

- if 0 ≤ a and 0 ≤ b then 0 ≤ a b

Because ≤ is a total order, for any number a, either 0 ≤ a or a ≤ 0 (in which case the first property above implies that 0 ≤  ). In either case 0 ≤ a2; this means that

). In either case 0 ≤ a2; this means that  and

and  ; so

; so  and

and  , which means

, which means  ; contradiction.

; contradiction.

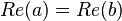

However, an operation ≤ can be defined so as to satisfy only the first property (namely, "if a ≤ b then a + c ≤ b + c"). Sometimes the lexicographical order definition is used:

- a ≤ b if

<

<  or (

or ( and

and  ≤

≤  )

)

It can easily be proven that for this definition a ≤ b implies a + c ≤ b + c.

Vector inequalities

Inequality relationships similar to those defined above can also be defined for column vector. If we let the vectors  (meaning that

(meaning that  and

and  where

where  and

and  are real numbers for

are real numbers for  ), we can define the following relationships.

), we can define the following relationships.

-

if

if  for

for

-

if

if  for

for

-

if

if  for

for  and

and

-

if

if  for

for

Similarly, we can define relationships for  ,

,  , and

, and  . We note that this notation is consistent with that used by Matthias Ehrgott in Multicriteria Optimization (see References).

. We note that this notation is consistent with that used by Matthias Ehrgott in Multicriteria Optimization (see References).

The property of Trichotomy (as stated above) is not valid for vector relationships. For example, when ![x = \left[ 2, 5 \right]^\mathsf{T}](../I/m/9d181beb090d8faf7950642e17d17d92.png) and

and ![y = \left[ 3, 4 \right]^\mathsf{T}](../I/m/d893e24b0332d1f3cca2a37352cc4a25.png) , there exists no valid inequality relationship between these two vectors. Also, a multiplicative inverse would need to be defined on a vector before this property could be considered. However, for the rest of the aforementioned properties, a parallel property for vector inequalities exists.

, there exists no valid inequality relationship between these two vectors. Also, a multiplicative inverse would need to be defined on a vector before this property could be considered. However, for the rest of the aforementioned properties, a parallel property for vector inequalities exists.

General Existence Theorems

For a general system of polynomial inequalities, one can find a condition for a solution to exist. Firstly, any system of polynomial inequalities can be reduced to a system of quadratic inequalities by increasing the number of variables and equations (for example by setting a square of a variable equal to a new variable). A single quadratic polynomial inequality in n-1 variables can be written as:

where X is a vector of the variables  and A is a matrix. This has a solution, for example, when there is at least one positive element on the main diagonal of A.

and A is a matrix. This has a solution, for example, when there is at least one positive element on the main diagonal of A.

Systems of inequalities can be written in terms of matrices A, B, C, etc. and the conditions for existence of solutions can be written as complicated expressions in terms of these matrices. The solution for two polynomial inequalities in two variables tells us whether two conic section regions overlap or are inside each other. The general solution is not known but such a solution could be theoretically used to solve such unsolved problems as the kissing number problem. However, the conditions would be so complicated as to require a great deal of computing time or clever algorithms.

See also

- Binary relation

- Bracket (mathematics), for the use of similar ‹ and › signs as brackets

- Fourier-Motzkin elimination

- Inclusion (set theory)

- Inequation

- Interval (mathematics)

- List of inequalities

- List of triangle inequalities

- Partially ordered set

- Relational operators, used in programming languages to denote inequality

Notes

References

- Hardy, G., Littlewood J.E., Pólya, G. (1999). Inequalities. Cambridge Mathematical Library, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-05206-8.

- Beckenbach, E.F., Bellman, R. (1975). An Introduction to Inequalities. Random House Inc. ISBN 0-394-01559-2.

- Drachman, Byron C., Cloud, Michael J. (1998). Inequalities: With Applications to Engineering. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98404-6.

- Murray S. Klamkin. ""Quickie" inequalities" (PDF). Math Strategies.

- Arthur Lohwater (1982). "Introduction to Inequalities". Online e-book in PDF format.

- Harold Shapiro (2005,1972–1985). "Mathematical Problem Solving". The Old Problem Seminar. Kungliga Tekniska högskolan. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "3rd USAMO". Archived from the original on 2008-02-03.

- Pachpatte, B.G. (2005). Mathematical Inequalities. North-Holland Mathematical Library 67 (first ed.). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-51795-2. ISSN 0924-6509. MR 2147066. Zbl 1091.26008.

- Ehrgott, Matthias (2005). Multicriteria Optimization. Springer-Berlin. ISBN 3-540-21398-8.

- Steele, J. Michael (2004). The Cauchy-Schwarz Master Class: An Introduction to the Art of Mathematical Inequalities. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54677-5.

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Inequality", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Graph of Inequalities by Ed Pegg, Jr., Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- AoPS Wiki entry about Inequalities