Indo-Aryan languages

| Indo-Aryan | |

|---|---|

| Indic | |

| Geographic distribution: | South Asia |

| Linguistic classification: |

|

| Subdivisions: |

|

| ISO 639-5: | inc |

| Linguasphere: | 59= (phylozone) |

| Glottolog: | indo1321[1] |

|

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins

|

|

Archaeology |

|

Peoples and societies

|

|

Religion and mythology |

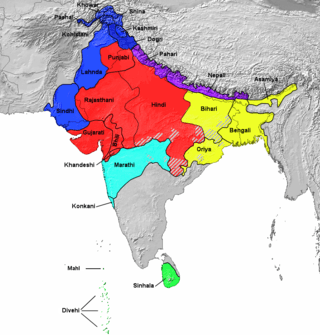

The Indo-Aryan (or Indic) languages are the dominant language family of the Indian subcontinent, spoken largely by Indo-Aryan people. They constitute a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages, itself a branch of the Indo-European language family. Indo-Aryan speakers form about one half of all Indo-European speakers (approx 1.5 of 3 billion), and more than half of all Indo-European languages recognized by Ethnologue.

The largest in terms of native speakers are Hindustani (Hindi-Urdu, about 240 million), Bengali (about 230 million), Punjabi (about 110 million),[2] Marathi (about 70 million), Gujarati (about 45 million), Bhojpuri (about 40 million), Oriya (about 30 million), Sindhi (about 20 million), Sinhala (about 16 million), Nepali (about 24 million), and Assamese (about 13 million), with a total number of native speakers of more than 900 million.

History

Indian subcontinent

- Old Indic (ca. 1500–300 BCE)

- early Old Indic: Vedic Sanskrit (1500 to 500 BCE)

- late Old Indic: Epic Sanskrit, Classical Sanskrit (500 to 300 BCE)

- Middle Indo-Aryan or Prakrits (ca. 300 BCE to 1500 CE) [see]

- Early Modern Indic (Mughal period, 1500 to 1800)

- early Dakkhini (Kalmitul-hakayat 1580)

- emergence of Khariboli (Gora-badal ki katha, 1620s)

Old Indo-Aryan

The earliest evidence of the group is from Vedic Sanskrit, the proto-language of the Indo-Aryan languages that is used in the ancient preserved texts of the Indian subcontinent, the foundational canon of Hinduism known as the Vedas. The Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni is of similar age to the language of the Rigveda, but the only evidence of it is a few proper names and specialized loanwords.

In about the 4th century BCE, the Vedic Sanskrit language was codified and standardized by the grammarian Panini, called "Classical Sanskrit" by convention.

Middle Indo-Aryan (Prakrits)

Outside the learned sphere of Sanskrit, vernacular dialects (Prakrits) continued to evolve. The oldest attested Prakrits are the Buddhist and Jain canonical languages Pali and Ardha Magadhi, respectively. By medieval times, the Prakrits had diversified into various Middle Indo-Aryan dialects. "Apabhramsa" is the conventional cover term for transitional dialects connecting late Middle Indo-Aryan with early Modern Indo-Aryan, spanning roughly the 6th to 13th centuries. Some of these dialects showed considerable literary production; the Sravakachar of Devasena (dated to the 930s) is now considered to be the first Hindi book.

The next major milestone occurred with the Muslim conquests on the Indian subcontinent in the 13th–16th centuries. Under the flourishing Mughal empire, Persian became very influential as the language of prestige of the Islamic courts due to adoptation of the foreign language by the Mughal emperors. However, Persian was soon displaced by Hindustani. This Indo-Aryan language is a combination with Persian elements in its vocabulary, with the grammar of the local dialects.

The two largest languages that formed from Apabhramsa were Bengali and Hindustani; others include Gujarati, Oriya, Marathi, and Punjabi.

New Indo-Aryan

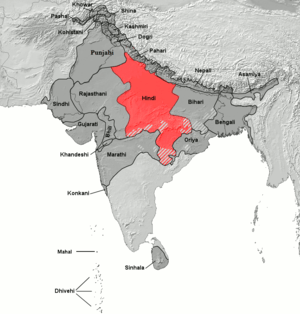

Dialect continuum

The Indo-Aryan languages of Northern India (that includes Assam Valley as for the language Assamese) and Pakistan form a dialect continuum. What is called "Hindi" in India is frequently Standard Hindi, the Sanskrit-ized version of the colloquial Hindustani spoken in the Delhi area since the Mughals. However, the term Hindi is also used for most of the central Indic dialects from Bihar to Rajasthan. The Indo-Aryan prakrits also gave rise to languages like Gujarati, Assamese, Bengali, Oriya, Nepali, Marathi, and Punjabi, which are not considered to be part of this dialect continuum.

Hindustani

In the Hindi-speaking areas, for a long time the prestige dialect was Braj Bhasha, but this was replaced in the 19th century by the Khariboli-based Hindustani. Hindustani was strongly influenced by Sanskrit and Persian, with these influences leading to the emergence of Modern Standard Hindi and Modern Standard Urdu as registers of the Hindustani language.[3][4] This state of affairs continued until the Partition of India in 1947, when Hindi became the official language in India and Urdu became official in Pakistan; because the basic grammar remains identical, the difference is more sociolinguistic than on actual language basis.[5][6][7]

Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni

Some theonyms, proper names and other terminology of the Mitanni exhibit an Indo-Aryan superstrate, suggesting that an Indo-Aryan elite imposed itself over the Hurrian population in the course of the Indo-Aryan expansion. In a treaty between the Hittites and the Mitanni, the deities Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and Nasatya (Ashvins) are invoked. Kikkuli's horse training text includes technical terms such as aika (eka, one), tera (tri, three), panza (pancha, five), satta (sapta, seven), na (nava, nine), vartana (vartana, turn, round in the horse race). The numeral aika "one" is of particular importance because it places the superstrate in the vicinity of Indo-Aryan proper as opposed to Indo-Iranian or early Iranian (which has "aiva") in general [8]

Another text has babru (babhru, brown), parita (palita, grey), and pinkara (pingala, red). Their chief festival was the celebration of the solstice (vishuva) which was common in most cultures in the ancient world. The Mitanni warriors were called marya, the term for warrior in Sanskrit as well; note mišta-nnu (= miẓḍha, ≈ Sanskrit mīḍha) "payment (for catching a fugitive)" (M. Mayrhofer, Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindoarischen, Heidelberg, 1986–2000; Vol. II:358).

Sanskritic interpretations of Mitanni royal names render Artashumara (artaššumara) as Arta-smara "who thinks of Arta/Ṛta" (Mayrhofer II 780), Biridashva (biridašṷa, biriiašṷa) as Prītāśva "whose horse is dear" (Mayrhofer II 182), Priyamazda (priiamazda) as Priyamedha "whose wisdom is dear" (Mayrhofer II 189, II378), Citrarata as citraratha "whose chariot is shining" (Mayrhofer I 553), Indaruda/Endaruta as Indrota "helped by Indra" (Mayrhofer I 134), Shativaza (šattiṷaza) as Sātivāja "winning the race price" (Mayrhofer II 540, 696), Šubandhu as Subandhu 'having good relatives" (a name in Palestine, Mayrhofer II 209, 735), Tushratta (tṷišeratta, tušratta, etc.) as *tṷaiašaratha, Vedic Tvastr "whose chariot is vehement" (Mayrhofer, Etym. Wb., I 686, I 736).

Romani language

The Romani language is usually included in the Central Indo-Aryan languages.[9] Romani is conservative in maintaining almost intact the Middle Indo-Aryan present-tense person concord markers, and in maintaining consonantal endings for nominal case – both features that have been eroded in most other modern languages of Central India. It shares an innovative pattern of past-tense person concord with the languages of the Northwest, such as Kashmiri and Shina. This is believed to be further proof that Romani originated in the Central region, then migrated to the Northwest.

There are no known historical documents about the early phases of the Romani language.

Linguistic evaluation carried out in the nineteenth century by Pott (1845) and Miklosich (1882–1888) showed that the Romani language is to be a New Indo-Aryan language (NIA), not a Middle Indo-Aryan (MIA), establishing that the ancestors of the Romani could not have left India significantly earlier than AD 1000.

The principal argument favouring a migration during or after the transition period to NIA is the loss of the old system of nominal case, and its reduction to just a two-way case system, nominative vs. oblique. A secondary argument concerns the system of gender differentiation. Romani has only two genders (masculine and feminine). Middle Indo-Aryan languages (named MIA) generally had three genders (masculine, feminine and neuter), and some modern Indo-Aryan languages retain this old system even today.

It is argued that loss of the neuter gender did not occur until the transition to NIA. Most of the neuter nouns became masculine while a few feminine, like the neuter अग्नि (agni) in the Prakrit became the feminine आग (āg) in Hindi and jag in Romani. The parallels in grammatical gender evolution between Romani and other NIA languages have been cited as evidence that the forerunner of Romani remained on the Indian subcontinent until a later period, perhaps even as late as the tenth century.

Classification

There can be no definitive enumeration of Indic languages, as their dialects merge into one another. Named languages are therefore social constructs as much as objective ones. The major ones are illustrated here; for the details, see the dedicated articles.

The classification follows Masica (1991) and Kausen (2006).

Dardic

The representative languages are:

Northern Zone

Northwestern Zone

- Dogri–Kangri (Western Pahari)

- Dogri, Kangri, Mandeali, etc.

- Punjabi (Eastern Punjabi)

- Lahnda (Western Punjabi)

- Sindhi

Western Zone

- Rajasthani

- Marwari, Rajasthani

- Gujarati

- Bhil

- Khandeshi

Central Zone (Madhya or Hindi)

- Western Hindi

- Hindustani, Haryanvi, etc.

- Eastern Hindi

- Fijian Hindi, Chhattisgarhi, etc.

Domari–Romani and related Parya historically belonged to the Central Zone but lost intelligibility with other languages of the group due to geographic distance and numerous grammatical and lexical innovations.

Eastern Zone (Magadhan)

These languages evolved circa 1000–1200 CE from eastern Middle Indo-Aryan dialects of Madhesh, Nepal such as the Magadhi Prakrit, Pali (the language of Gautama Buddha of Nepal and the major language of Buddhism), and Ardhamagadhi ("Half-Magadhi") from a dialect or group of dialects that were close, but not identical to, Vedic and Classical Sanskrit.[10]

Bhojpuri (incl. Caribbean Hindustani), though it is an eastern Indo Aryan language, it is more similar to Central group.

Southern Zone languages

These group of languages developed from Maharashtri. It is not clear if Dakhini (Deccani, Southern Urdu) is part of Hindustani along with Standard Urdu, or a separate Persian-influenced development from Marathi.

Konkani

The insular languages share several characteristics that set them apart significantly from the continental languages.

Unclassified

The following languages are related to each other, but otherwise unclassified within Indic:

Kuswaric[11]

- Dhanwar (Rai), Bote and Darai

Chinali–Lahul Lohar[12]

The following other poorly attested languages are listed as unclassified within the Indo-Aryan family by Ethnologue 17:

- Kanjari (Punjabi?), Od (Marathi?), Vaagri Booli, Degaru, Andh, Kumhali, Mina (not a distinct language?), Bhalay-Gowlan (perhaps in Southern), Sonha (perhaps in Central).

Phonology

Consonants

Stop positions[13]

The normative system of New Indo-Aryan stops consists of five points of articulation: labial, dental, "retroflex", palatal, and velar, which is the same as that of Sanskrit. The "retroflex" position may involve retroflexion, or curling the tongue to make the contact with the underside of the tip, or merely retraction. The point of contact may be alveolar or postalveolar, and the distinctive quality may arise more from the shaping than from the position of the tongue. Palatals stops have affricated release and are traditionally included as involving a distinctive tongue position (blade in contact with hard palate). Widely transcribed as [tʃ], Masica (1991:94) claims [cʃ] to be a more accurate rendering.

Moving away from the normative system, some languages and dialects have alveolar affricates [ts] instead of palatal, though some among them retain [tʃ] in certain positions: before front vowels (esp. /i/), before /j/, or when geminated. Alveolar as an additional point of articulation occurs in Marathi and Konkani where dialect mixture and others factors upset the aforementioned complementation to produce minimal environments, in some West Pahari dialects through internal developments (*t̪ɾ, t̪ > /tʃ/), and in Kashmiri. The addition of a retroflex affricate to this in some Dardic languages maxes out the number of stop positions at seven (barring borrowed /q/), while a reduction to the inventory involves *ts > /s/, which has happened in Assamese, Chittagonian, Sinhala (though there have been other sources of a secondary /ts/), and Southern Mewari.

Further reductions in the number of stop articulations are in Assamese and Romany, which have lost the characteristic dental/retroflex contrast, and in Chittagonian, which may lose its labial and velar articulations through spirantization in many positions (> [f, x]).

| Stop series | Language(s) |

|---|---|

| /p/, /t̪/, /ʈ/, /tʃ/, /k/ | Hindi, Punjabi, Dogri, Sindhi, Gujarati, Bihari, Maithili, Sinhala, Oriya, Standard Bengali, dialects of Rajasthani (except Lamani, NW. Marwari, S. Mewari) |

| /p/, /t̪/, /ʈ/, /ts/, /k/ | Nepali, E. and N. dialects of Bengali (Dacca, Maimansing, Rajshahi), dialects of Rajasthani (Lamani and NW. Marwari), Northern Lahnda's Kagani, Kumauni, many West Pahari dialects (not Chamba Mandeali, Jaunsari, or Sirmauri) |

| /p/, /t̪/, /ʈ/, /ts/, /tʃ/, /k/ | Marathi, Konkani, certain W. Pahari dialects (Bhadrawahi, Bhalesi, Padari, Simla, Satlej, maybe Kulu), Kashmiri |

| /p/, /t̪/, /ʈ/, /ts/, /tʃ/, /tʂ/, /k/ | Shina, Bashkarik, Gawarbati, Phalura, Kalasha, Khowar, Shumashti, Kanyawali, Pashai |

| /p/, /t̪/, /ʈ/, /k/ | Rajasthani's S. Mewari |

| /p/, /t/, /k/ | Assamese |

| /p/, /t/, /tʃ/, /k/ | Romani |

| /t̪/, /ʈ/ | Chittagonian |

Nasals[14]

Sanskrit was noted as having five nasal-stop articulations corresponding to its oral stops, and among modern languages and dialects Dogri, Kacchi, Kalasha, Rudhari, Shina, Saurasthtri, and Sindhi have been analyzed as having this full complement of phonemic nasals /m/ /n/ /ɳ/ /ɲ/ /ŋ/, with the last two generally as the result of the loss of the stop from a homorganic nasal + stop cluster ([ɲj] > [ɲ] and [ŋɡ] > [ŋ]), though there are other sources as well.

Charts

The following are consonant systems of major and representative New Indo-Aryan languages, as presented in Masica (1991:106–107), though here they are in IPA. Parentheses indicate those consonants found only in loanwords: square brackets indicate those with "very low functional load". The arrangement is roughly geographical.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Language comparison chart

| English | Vedic Sanskrit | Gujarati | Marathi | Hindustani | Punjabi | Sindhi | Bengali | Kashmiri | Bhojpuri | Oriya | Assamese | Maithili | Sinhala | Nepali | Pali | Romani | Saraiki (Southern Punjabi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| beautiful | sundara | sundar | sundar | sundar | sohnā | suhɳā | shundor | sondar | suhnar/khapsoorat | sundara | dhuniya, xundôr | sundar | sonduru,sundara | sundar | sundaro | shukar | sohnra |

| blood | rakta, loha | lohi, khoon, rakt | rakta | khūn, rakta, lahū | lahū, khūn | ratu | rôkto, lohit, lohu | ratth | khūn, lahū | rakta | tez | shonit | le,rudiraya,ruhiru | ragat | rat | laho, rat | |

| bread | rotika | paũ, roṭlā | chapāti, poli, bhākarī | chapātī, roṭī | roṭi | pʰulko | (pau-)ruṭi | tçhot | roṭī | pauruṭi | pauruti | roṭi | paan | paũroṭi | manro | roti, ma(n)ri, dhodha | |

| bring | anayati | lā- | ān- | lā- | lyā | ɖe | ano | ann | lāv- | nai an- | an- | anaah | ghenna | lyaunu | anel | ghin aa, Lai aa | |

| brother | bhrātṛ, bandhu | bhāi | bhau, bandhu | bhāī | prā, pāi, vīr | bʱau | bhai | boéy | bhāī, bhaīyā | bhai, bhaina | bhaiti | sahodaraya, beeya | bhaai, dai, daju | phral | bhrā, vīr, lala | ||

| come | āgatah | āv- | yē | ā- | ā, āo, ājā | ach | asho, ai | vall | āv- | ās-, ā- | ānha, ānhok | ā- | enna | āunu | āgachcha | āvel | āo |

| cry | rodana, rava | raḍ- | raḍ- | rō- | rō- | rōaɳ | kãd, kando-, rodan | wódun | ro- | kanda | kand- | adanawa,handanawa | runu | rodanam | rovel | rovanra | |

| dark | andhaḥkāra | andhārũ | andhār | andhera | hanerā | ôndʱah | ôndhokar, ãdhar | anyí-got | anhār, anhera | andhāra | andhar, ôndhôkar | anduru,andhakara | andhyaro | andhakaaro | kalo | andhara | |

| daughter | putrī, duhitṛ | chhokḍi | lek, mulagī, poragī | beṭi | tī, kuri | dʱī | me-lok | koor | dhiyā, beṭi, chhori | jhiya | ziyari, ziyek | duva,du | chhori | chhai | Dhee | ||

| day | divasa, dina | divas | divas, din,dina | din | din, dihara | ɖīhn | din, dibôsh | dóh | din | dina | din | dinaya,dawasa | din | dives | denh, jehara | ||

| do | karoti | kar- | kar- | kar- | kar- | kar- | koro | kar | kar- | kara- | kôr- | kar- | karanna | garnu | kerel | karo | |

| door | dvāra, kapāṭa | kerel | dār, darvāzā | darvāzā, kavad | būha, dar, darvāza | darvāzo | dôrja, dur | darwaaz, dār, daer ("window") | darvājā, kevadi | daraja, kabata | duar, dôrza | dora,duwaraya | dhoka | vudar | buha, dar | ||

| die | mar-, glah- | mar- | mar- | mar-, mar jā- | mar-, mar ja- | mar- | môr, more ja-, mara ja- | marun | mu, mar ja | mar- | môr- | maranaya,maruna | marnu | merel | marna | ||

| egg | aṇḍa, ḍimba | iṇḍũ | aṇḍa | anḍā | aṇḍā | aṇɖo, bedo | ḍim | thool | anḍā | anḍā, ḍimba | koni | bitharaya,biju | andaa | anro | anda, aana | ||

| salt | kṣāra, sala, lavaṇa | mithu | lavan/meeth | namak | lūn/nūn namak | lūn | lobon/noon | noon | noon/namak | labana | labon | nimak/noon | lunu | nun | khar/lavan | lon | loon/noon |

| earth | pṛthvi, mahi, bhuvana, dharitrī | pruthvi | pruthvi, dharani | prithvī, dhartī, zamīn | jag, jahān, tarti, zamīn | dhartī | prithibi, duniya | daertī (voiced-aspirated /dh/ > /d/) | jamīn, pirthvi | pruthibi | prithibi | pruthuvi,polova,bhoomi,bima | prithivi | phuv | zameen, dharti | ||

| eye | netra, lochna | āñkh | netra, ḍoḷā | āñkh | akh | akh | chokh | aéchh | āñkh | ākhi | soku | ainkh | asa,akshi,neth,nuwan | aankha | yakh | akh | |

| father | pitra, janaka | bāp | pitā, vaḍil, bāba | bāp | piyō, abba | piu, baba | bābā, abbā, bap | mol, bab | bāp, bābuji, pitāji | bāpa, bābā | dêuta | piya,thatha | buwā, pitā | dad | abbā, piyoo | ||

| fear | bhaya, bhi | bik, ḍar | bhītī, bhaya, ghābra | ḍar, ghabrāhat | ḍar | ɖapu | bhôe, ḍôr | dar | ḍar | ḍara | bhoi | bhay | baya,biya | dar | dar, trash | darr | |

| finger | aguli, aguliyaka | āñgḷi | bōt | anguli, ungli | ungal, ungli | aŋur | ang-gul | ungij | anguri | ānguthi | anguli | āngur | angili | aunla | angusht | ungil | |

| fire | agni, bhujyu | agni, jvaḷa | āg, agni, jāl | āg | agg | bāh | agun | agénn, nār | āgh | agni, nia | zui | agni,gini | āgo | manta | yag | bhaa | |

| fish | matsya | māchhli | māsa | machhlī | machhī | machhī | machh | gāda | machhri | mācha | mas | masun,mathasya,malu | māchā | machho | machhey | ||

| food | bhojana, khadati | anna, khorāk, poshaṇ | jēvana, bhojan | khānā, bhojan | khānā | khādho,ann, māni | khabar | khyann | khana, ann-roti | khādya, bhojana | ahar, khaiddyô, khuwa bostu | āhāra,kema,bojun,bhojana | khānā, anna, āhār | xal | roti-tukkur, khanra | ||

| go | gachati | jā- | jā- | jā- | jā- | vaɲ | ja-, jao-, gê- | gatçh | jā | ja- | zu-, za- | yanna | janu | jal | vanj | ||

| god | deva, ishwara, parmeshwara, devata | parmeshvar, dev, bhagvān | dev, parmeshwar, ishwar | bhagvān, parmeshvar, ishvar, khudā | pagvān, rab, waheguru, khudā | bhagvān, parmeshvar, ishvar, khudā, sāin, mālik | bhôgoban, rab, ishshor, khoda | dai, divta, bagvān, parmeeshar | bhagvān, mālik, iswar, daiva, daiya | bhagabāna, ṭhākura, diyan | debôta, bhôgôwan | devi,devathava | bhagawaan, dewataa, ishwor | devel | rab, mālik | ||

| good | shobhna, uttama | sārũ | changla | achhā | changa, wadia, palā | suʈʰo | bhalo | rut (moral "good"), jān (physical "good") | badhiya, changa, achha | bhāla | bhal | neek, neeman | hondhai | raamro | lachho, mishto | changa | |

| grass | truna, kusha | ghāsthāro | gavata | ghās | kāh | ghãhu | ghash | dramunn | ghās | ghāsa | ghã | thana,thruna | ghaas | char | ghā | ||

| hand | hasta | hāth | hāt | hāth | hath | hatʰu | hat | atth | hāth | hāta | hat | atha,hasthaya | hāt | vast | hat | ||

| head | shira, mastaka, kapāla | māthũ | ḍoke | sir, shīsh | sir, sīs | matʰo | matha | kalla | sīr | munḍa | mur | oluwa,sirasa | tauko, seer | shero | ser | ||

| heart | hrdaya | hruday | rudaya | dil | dil | dil | hridôe | ryeda | dil, hivara, jiyara | hrudaya | hridai, hiyan | hada,herdaya | hridaya, mutu | ilo | Dil | ||

| horse | ashva, ghotaka, hayi | ghoḍũ | ghoda | ghoṛa | koṛa | ghoɽʱo | ghoṛa | gur | ghoṛa | ghoda | ghůra | ashvaya,thuranga | ghoda | khoro, grast | ghora | ||

| house | graha, alaya | ghar | ghar | kār | ghôr | ɡʱar, jaɡʱah | gar (voiced-aspirate /gh/ > /g/) | ghar | ghara | ghôr | gedhara,gruha | ghar | kher | ghar | |||

| hunger | bubuksha, kshudhā | bhukh | bhūkh | bhūkh | pukh | bhūkhayal | khide | bo'tchh | bhūkh | bhoka | bhuk | kusagini,badagini | bhok | bokh | bhuk | ||

| language | bhasha, vaani | bhāshā | bhāshā | bhāshā, zabān | boli, zabān, pasha | ɓoli, bhasha, zabān | bhasha | booyl, zabān | bhākhā, boli, jubaan | bhāsā | bhaxa | bhāshā | bhashawa,basa | bhaashaa | chhib | boli, zaban | |

| laugh (v.) | hāsa, smera | has- | hās- | hãs- | has- | kʰillu | hãsh- | assun | hãs- | hās- | hã- | hina,sinaha,sina | hasnu | asal | khill | ||

| life | jivana, jani | jivan, jindagi | jīvan, jīv | jīvan, zindagī | jindrī, jīvan, zindagi | zindagī | jibon | zoo, zindagayn | jinigi | jibana, prāna | zibôn | jiban | jeevithe | jeewan, jindagi | jivipen | zindgey | |

| moon | chandramā, soma, māsa | chandra, chāndo | chandra | chandramā, chandā, chānd | chann, chānd | chanɖ | chãd, chôndro | tçandram | channa, channarma, mah | chandra | zunbai | chandra,sandu,handa | chandramā, juun | chhon | chandr | ||

| mother | janani, martr | mā, bā | āi, māi | mā | mā, bebe, amma | māo, amma | ma, amma, mao | maeyj | matāri, māi, amma | mā, bou | ai, ma | myay | mawa,amma,matha | aamaa, maataa | dai | amma, maa | |

| mouth | moḍhũ, mukh | tond, mukha | mūñh | mūñh, mukh | mūñh, vāt | aaes | mūñh | mukh | mukh | moonh | mukha, kata | mui | mukh | ||||

| name | nāma | nām | nāv | nām | nā | nālo | nam | naav | nā, nām | nāma, nā | nam | nām | nama | nām | nav | nā | |

| night | raatri, rajani | rāt, rātri, nishā | rātra | rāt, rātri, nishā | rāt | rāt | rat, ratri, ratro | raath | rāt | rāti | rati | rat | rāthriya,rae | raat, raatri | raat | ||

| open | uttana, udhatita | khullũ | khol, ughad | khulā | khulla, khol | khol | khola | khol | khullā | kholā | khula | harinna | khulla | rat | khulla | ||

| peace | shānti | shānti, shāntatā | shānti | shānti, aman | shānti, aman, sakūn | shānti, aman | shanti | aman, shaenti | sānti-sakoon, aman | sānti | xanti | shaanti, aman | samaya,shāntiya | shaanti | kotor | aman, sakoon | |

| place | stapana, sthala, bhu | jagyā, sthaļ | sthān, sthal, jāga | sthān, jagah | jagā, thāñ, asthān | jaɠah, thāñ | jaega, sthan, jomin | jaay | jagah | jāgā | thai | sthanaya | thaaun, sthal | than | jaga | ||

| queen | rāni, rājpatni | rāṇi, madhurāṇi | rāni, rājmātā | rāni, malkā | rāni, malka | rāɳi | rāni | māhraeny (also used for "newly-wed bride") | rāni, begam | rāṇi | rani | rajina,devi,bisawa | rāni | rani, thagarni | ranri, malka | ||

| read | pathati, vachana | vānch- | vāch- | paṛh- | paṛh- | paɽʱ- | pôṛ- | parun | paṛh- | paḍh- | pôṛh- | kiyawanna | padh- | chaduvu | parhnra, parh | ||

| rest | vishrama | ārām | vishrām | ārām | arām | ārām | aram, bishrom | araam | rām | ārām, visrām | zirani | vishrāma shalawa,thanayama | ārām, bishrām | Araam | |||

| say | vadati, vadanti | bōl- | bōl-, sāng- | bōl-, keh- | bōl, ākh, keh | cau - chau | bôl- | vann | bōl- | kah- | kũ- | baiju | pawasanna,kiyanna | bhannu | phenel | bol, aakh | |

| sister | svasr, bhagini | bêhn | bhagini, baheen | behn | pēn, didi | bēɳ | bon, apa, didi | baeynn | bahin, didi, didiya | bhauṇi | bhonti | bahin | bhaen,bhaengi | sohouri,souri | phen | bheinr | |

| small | alpa, laghu, kanishtha | nāhnũ | lahān, laghu | chhoṭā | nikka, chhoṭā | nanɖo | chhoṭo | lokutt, nyika, pyoonth | chhoṭ, nanhi | choṭa, sana | xoru | chhoit | chuti,podi | saano | tikno, xurdo | nikka, chauta | |

| son | sunu, putra | chhokḍo | mulgā | bēṭā | put, puttar, munḍa | puʈ | chhele, pola | nyechu, pothur | putt/chhora | pua | putek | puthra,putha,puthu | chhora | chhavo | putr | ||

| soul | ātmā, atasa | ātmā | ātmā | ātmā, rūh | ātmā, rūh | ātmā, rūh | attã, ãtta | āthmā | rūh | ātmā | ātmā | ātmā | ātmā | di | rooh | ||

| sun | sūrya | sūraj, sūrya | sūrya | sūrya, sūraj | sūraj | siju | shūrjo, roud | siri | sūraj | sūrjya | xuirzyô, baeli | sūraj | ira,hiru,sūrya | sūrya | kham | sijh | |

| ten | dasha | das | dahā | das | das, daha | ɖaha | dôsh | duh | das | dasa | dôh | dahaya,dasa | dus | desh | dah | ||

| three | trī, trayah | traṇ | tīn | tīn | tin | ʈeh | tin | t're | tīn | tini | tini | thuna | tin | trin | trai | ||

| village | grāma | gāñḍu | gāv, khēda | gāoñ | pinḍ, gāñ | ɠoʈʰ | gram, gaon | gām | gāoñ-dehāt, jageer | gān, grāma | gaon | gama,gramaya | gaun | gav | dehat, jhoauk, vasti | ||

| want | ichhati, kankshati, amati, apekshita | joi- | pāhijē, havē | chāh- | chāh- | kʰap, chāh- | chāh- | yatshun, kan'tchun | chāh- | darakara | lôg- | oone,awashyayi | chaahanaa | kamel, mangel | chah | ||

| water | pāniya, jala | pāṇi | pāṇi | pāni, jal | pāni, jal | pāṇi | pāni, jôl | poyn, zal (used for "urine" only) | pāni | pāṇi, jala | pani | jalaya,wathura,paen | pāni, jal | pani | panri | ||

| when | kada, ched | kyahre | kēvhā, kadhee | kab | kad, kadoñ | kaɖahn | kôkhon, kôbe | karr | kab | kebe | ketiyan | kakhan, kahiya | kawadhada,kedinada | kahile | kana | kadanr | |

| wind | pavan, vāyu, vātā | havā, pavan | vāra | havā, pavan | havā, paun | havā | batash, haoa | tshath, hava | hāvā | pabana | bôtãh | hulan, sulan, pavana, vathaya | huri, batas | balval | hava, phook | ||

| wolf | vrka, shvaka | shiyāl | kōlha | bhēṛhiyā | pēṛhiyā, baghiyār | ɡidʱar | sheal | vrukh | bhērhiyā | gadhiyā | xiyal | siyār | vurkaya | shyaal, bwanso | ruv | baghiyaar | |

| woman | nāri, vanitā, strī, mahilā, lalanā | mahilā, nāri | bāi, mahilā, stree | aurat, strī, mahilā, nāri | aurat, zanāni, tīvīn | māi | mohila, nari, shtri | zanaan | mehraru, aurat, janaani | stree, nāri | mohila, maiki manuh | kanthawa,gahaniya,sthriya,

mahilawa,lalanawa,liya,landa,vanithawa |

mahilaa, naari, stree | juvli | aurat, treimat, zaal, zanaani | ||

| year | varsh, shārad | varash | varsh | sāl, varsh | sāl, varah | sāl | bôchhor | váreeh | sāl | barsa | bôsôr | barxa | varshaya | barsha | bersh | saal | |

| yes / no | hyah, kam / na, ma | hā / nā | hōy, hō, hā / nāhi, nā | hāñ / nā, nahīñ | hāñ, āho / nā, nahīñ | hā/ na | hê, hoi, ho, oi / na | aa / ná, ma | hāñ / nā | han / | hoi / nohoi | ow / nā | ho / hoina, la / nai | va / na | ha / na | ||

| yesterday | hyah, gatdinam, gatkale | (gai-)kāl(-e) | kāl | kal | kal | kal | (gôto-)kal(-ke) | kāla, rāth | kālh | (gata-)kāli | (zuwa-)kali | ēyeh | hijo | ij | kal | ||

| English | Vedic Sanskrit | Gujarati | Marathi | Hindi | Punjabi | Sindhi | Bengali | Kashmiri | Bhojpuri | Oriya | Assamese | Maithili | Sinhala | Nepali | Pali | Romani | Saraiki (Southern Punjabi) |

See also

- Indo-Aryans

- Indo-Iranians

- Indo-Aryan migration

- Proto-Vedic Continuity

- The family of Brahmic scripts

- Linguistic history of India

- Indo-Aryan loanwords in Tamil

References

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Indo-Aryan". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ "världens-100-största-språk-2010". Nationalencyclopedin. Govt. of Sweden publication. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ Kulshreshtha, Manisha; Mathur, Ramkumar (24 March 2012). Dialect Accent Features for Establishing Speaker Identity: A Case Study. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4614-1137-6.

- ↑ Robert E. Nunley, Severin M. Roberts, George W. Wubrick, Daniel L. Roy (1999), The Cultural Landscape an Introduction to Human Geography, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-080180-1,

... Hindustani is the basis for both languages ...

- ↑ "Urdu and its Contribution to Secular Values". South Asian Voice. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ↑ "Hindi/Urdu Language Instruction". University of California, Davis. Retrieved 3 Jan 2015.

- ↑ "Ethnologue Report for Hindi". Ethnologue. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- ↑ Paul Thieme, The 'Aryan' Gods of the Mitanni Treaties. JAOS 80, 1960, 301–17

- ↑ "Romani (subgroup)". SIL International. n.d. Retrieved September 15, 2013.

- ↑ Oberlies, Thomas Pali: A Grammar of the Language of the Theravāda Tipiṭaka, Walter de Gruyter, 2001.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Kuswaric". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "Chinali–Lahul Lohar". Glottolog. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Masica (1991:94–95)

- ↑ Masica (1991:95–96)

- John Beames, A comparative grammar of the modern Aryan languages of India: to wit, Hindi, Panjabi, Sindhi, Gujarati, Marathi, Oriya, and Bangali. Londinii: Trübner, 1872–1879. 3 vols.

- Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh, eds. (2003), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Madhav Deshpande (1979). Sociolinguistic attitudes in India: An historical reconstruction. Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers. ISBN 0-89720-007-1, ISBN 0-89720-008-X (pbk).

- Chakrabarti, Byomkes (1994). A comparative study of Santali and Bengali. Calcutta: K.P. Bagchi & Co. ISBN 81-7074-128-9

- Erdosy, George. (1995). The Indo-Aryans of ancient South Asia: Language, material culture and ethnicity. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-014447-6.

- Kobayashi, Masato.; & George Cardona (2004). Historical phonology of old Indo-Aryan consonants. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. ISBN 4-87297-894-3.

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Misra, Satya Swarup. (1980). Fresh light on Indo-European classification and chronology. Varanasi: Ashutosh Prakashan Sansthan.

- Misra, Satya Swarup. (1991–1993). The Old-Indo-Aryan, a historical & comparative grammar (Vols. 1–2). Varanasi: Ashutosh Prakashan Sansthan.

- Sen, Sukumar. (1995). Syntactic studies of Indo-Aryan languages. Tokyo: Institute for the Study of Languages and Foreign Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Vacek, Jaroslav. (1976). The sibilants in Old Indo-Aryan: A contribution to the history of a linguistic area. Prague: Charles University.

External links

- The Indo Aryan languages, 10-25-2009

- The Indo-Aryan languages Colin P.Masica

- Survey of the syntax of the modern Indo-Aryan languages (Rajesh Bhatt), February 7, 2003.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||