Indiana in the American Civil War

|

|

Union states in the American Civil War |

|---|

|

| Border states |

|

| Dual governments |

| Territories and D.C. |

|

Indiana, a state in the Midwestern United States, played an important role during the American Civil War. Despite significant anti-war activity in the state and southern Indiana's ancestral ties to the Southern United States, it was a mainstay of the Union war effort, and hunted down disloyal elements. During the course of the war, Indiana contributed approximately 210,000 soldiers and millions of dollars of horses, food and supplies to the U.S. Army. Residents of Indiana, also known as Hoosiers, served in every major engagement of the war and almost every engagement—minor or otherwise—in the western theater of the war. Indiana, an agriculturally rich state containing the fifth-highest population in the Union and sixth-highest of all states, was critical to Northern success.

The state experienced political strife when Governor Oliver P. Morton suppressed the Democratic Party-controlled General Assembly, which had a large Copperhead element that opposed the war. The action left the state without the authority to collect taxes but the Governor used private funds rather than rely on the legislature. The state experienced two minor raids by Confederate forces and one major raid in 1863, which caused a brief panic in southern portions of the state and in the capital city, Indianapolis.

The American Civil War altered Indiana's society, politics, and economy, beginning a population shift northward and leading to a relative decline in the agrarian southern part of the state. Wartime federal policies regarding banks, railroads, and industry fostered industrial and financial modernization and led to an increase in the standard of living.

Indiana's contributions

| War | American Civil War |

| Started | April 12, 1861 |

| Ended | April 9, 1865 |

| Soldiers | 208,367 Hoosiers |

| Sailors | 2,130 Hoosiers |

| Killed | 24,416 Hoosiers |

| Wounded | 50,000 Hoosiers |

| Result | Union victory |

Indiana was the first state in what was then considered the American Northwest to mobilize for the Civil War. News of the attack on Fort Sumter, which began the war, reached Indiana on April 12, 1861. On the next day, two mass meetings were held in the state and the state's position was decided: Indiana would remain in the Union and would immediately contribute men to suppress the rebellion. On April 14, Governor Morton issued a call to arms in order to raise men to meet the quota set by President Abraham Lincoln.[1] Indiana had the fifth-largest population of any state that remained in the Union, and was important for its agricultural yield which became even more valuable to the Union after the loss of the rich farmland of the South. These factors made Indiana critical to the Union's success.[2][3]

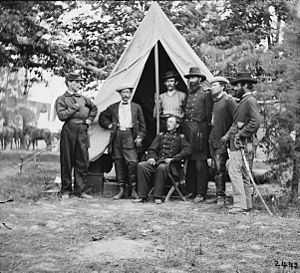

Lincoln initially requested that Indiana send 7500 men to join the Union Army. Five hundred men assembled the first day, and within three weeks, more than 22,000 men had volunteered—so many that thousands had to be turned away.[4] Before the war ended, Indiana contributed a total of 208,367 men, 15% of the state's total population, to fight and serve in the Union Army, and 2,130 to serve in the Union Navy.[4][5] Most of the soldiers from Indiana were volunteers, and 11,718 men reenlisted at least once.[6] The state only turned to conscription towards the end of the war, and a relatively small total of 3003 men were drafted. These volunteers and conscripts allowed the state to supply the Union with 126 infantry regiments, 26 batteries of artillery, and 13 regiments of cavalry.[7][8] By the end of the war, 46 general officers in the Union army had resided in Indiana at some point in their lives.[9]

More than 35% of the Hoosiers who entered the Union Army became casualties: 24,416 (about 6.75% of total war casualties) lost their lives in the conflict, and more than 50,000 were wounded.[6]

More than 60% of Indiana's regiments were mustered and trained in Indianapolis, the state capital. The state government financed a large portion of the costs involved, including barracking, feeding, and equipping the soldiers prior to their being sent as reinforcements to the standing Union armies. Indiana also maintained a state-owned arsenal in Indianapolis that served the Indiana home guard and as a backup supply depot for the Union Army.[10]

The War Department established one of the United States' first national cemeteries, New Albany National Cemetery, for the war dead in New Albany, Indiana. Port Fulton, Indiana, in present-day Jeffersonville, was home to the third-largest Union military hospital, Jefferson General Hospital. Indianapolis was the site of Camp Morton, one of the Union's largest prisons for captured Confederate soldiers, with Lafayette, Richmond, and Terre Haute occasionally holding prisoners of war as well.[11]

Conflicts

Indiana regiments were present on most battlefields of the Civil War and saw much fighting outside of the state. Only one significant conflict, which caused a brief panic in Indianapolis and southern Indiana, occurred on Indiana soil during the war.

Raids

Confederate officer Adam Johnson briefly captured Newburgh, Indiana, on July 18, 1862, during the Newburgh Raid. Johnson convinced the Union troops garrisoning the town that he had cannon on the surrounding hills, when in fact they were merely camouflaged stovepipes. The raid convinced the federal government that it was necessary to supply Indiana with a permanent force of regular Union Army soldiers to counter future raids.[12]

The one major incursion into Indiana by the Confederate Army was Morgan's Raid. The raid occurred in July 1863 and was a Confederate cavalry offensive by troops under the command of John Hunt Morgan. In preparation for Morgan's planned raid, Hines' Raid, a minor incursion, was carried out by troops under Thomas Hines in June 1863.[13]

On July 8, 1863, Morgan crossed the Ohio River at Mauckport with 2,400 troopers. His landing was initially contested by a small party of the Indiana Legion, who withdrew when Morgan began firing artillery from the southern shore of the river. The militia quickly retreated towards Corydon, where a larger body of militia was gathering to block Morgan's advance. Morgan advanced rapidly on Corydon and fought the Battle of Corydon. After a short, fierce fight, Morgan took command of high ground south of the town. Corydon promptly surrendered after Morgan's artillery fired two warning shots into the town from the high ground. The town was sacked, but little damage was done to buildings in the town. Morgan continued his raid by moving northward and burning most of the town of Salem.[14]

His movements appeared to be a charge at Indianapolis, and panic spread through the capital. Governor Morton had called up the state militia as soon as Morgan's intention to cross into the state was known. More than 60,000 men of all ages came out to repel Morgan's raid. Morgan considered attacking Camp Morton in Indianapolis to free more than 5,000 Confederate prisoners of war imprisoned there, but decided against it. After destroying Salem, Morgan turned abruptly eastward and began moving towards Ohio. He continued to raid and pillage his way toward the Indiana-Ohio border until he left Indiana on July 13 as several Union armies began to converge on him. By the time he left, his raid had become a desperate attempt to escape back to the South.[15]

Indiana regiments

Many of Indiana's 165 regiments served with distinction in the war.[8] The regiments each consisted of approximately 1,500 men when formed, but as their numbers declined due to casualties, smaller regiments were merged. The first six regiments mustered at the start of the war were enlisted for six months and were put into action in the western theater.[8] Their short terms of service and few numbers were inadequate for the task of fighting the war, and by the end of 1861, Indiana fielded an additional sixty-five regiments whose men enlisted for terms of three years.[8] These three-year regiments were employed in large part in the western theater. As the war progressed, another forty-eight regiments were mustered in 1862, with about half being sent to the eastern theater, and the other half remaining in the west.[8] During 1863, eighteen regiments were raised to replace the casualties of the first two years' fighting.[8] During Morgan's Raid of that year, ten temporary regiments were created and enlisted for terms of three months apiece, but disbanded once the threat posed by Morgan was gone.[8] The last twenty-five regiments created in the state were mustered in 1864, and served until the end of the war. Most of Indiana's regiments were mustered out and disbanded by the end of 1864 as fighting declined, but some continued in service. The 13th Regiment Indiana Cavalry was the last regiment from the state to be mustered out of the U.S. Army, leaving service on November 10, 1865.[8]

The 19th Indiana Volunteer Infantry Regiment served as part of the Iron Brigade. The 19th made critical contributions to some of the most important engagements of the war, including the Second Battle of Bull Run, but was almost completely destroyed in the Battle of Gettysburg.[16]

The 14th Indiana Infantry Regiment, also called the Gallant Fourteenth, was another notable Indiana regiment. In the Battle of Gettysburg, it was the regiment that secured Cemetery Hill on the first day of the three-day fight. Another famous regiment was the 9th Indiana Infantry Regiment, which fought in many major battles and was among the first Hoosier regiments to see action in the war.[17]

The 28th Indiana Colored Infantry Regiment was formed on March 31, 1864, at Camp Fremont in Indianapolis near what is now the Fountain Square district. It was the only black regiment formed in Indiana during the war and lost 212 men during the conflict.[18] The regiment signed on for 36 months, but the war was effectively over in fewer than eleven months from their enlistment, cutting the regiment's length of service short.[18]

The last casualty of the Civil War was a Hoosier of the 34th Regiment Indiana Infantry. Private John J. Williams died at the Battle of Palmito Ranch on May 13, 1865.[19]

Politics

Although winning only 40% of the vote nationwide in 1860, Abraham Lincoln won Indiana's 13 electoral votes with 51.09% of the vote statewide, compared to Stephen Douglas's 42.44%, John Breckenridge's 4.52%, and John Bell's 1.95%.[20]

Due to their location across the Ohio River from Louisville, Kentucky, the Indiana cities of Jeffersonville, New Albany, and Port Fulton saw increased trade and military activity. Some of this increase was due to Kentucky's desire to stay neutral in the war. In addition, Kentucky was home to many Confederate sympathizers, and bases were needed for Union operations against Confederates in Kentucky. Militarily, it was safer to store war supplies in towns on the north side of the Ohio River. Camp Joe Holt was established between Jeffersonville and New Albany in what is the present-day visitor's center of the Falls of the Ohio State Park in Clarksville, Indiana. Towards the end of the war, Port Fulton was home to the third-largest hospital in the United States, Jefferson General Hospital.[21]

Southern influence

In 1861, when Kentucky governor Beriah Magoffin refused an order to allow pro-Union forces to mobilize in his state—he issued a similar order regarding Confederate forces—Indiana governor Morton issued orders allowing loyal Kentuckians to join Indiana regiments. Many Kentucky troops, especially from the city of Louisville, joined Hoosier regiments at Camp Joe Holt. Morton repeatedly came to the military rescue of Kentucky's pro-Union government during the war and became known as the "Governor of Indiana and Kentucky." Morton also was called the "Soldier's Friend" because he organized the General Military Agency of Indiana, the Soldiers' Home, Ladies' Home, and Orphans' Home to help meet the needs of Indiana's soldiers and their families. Morton also established an arsenal in Indianapolis to supply the Indiana Militia, Home Guard, and the federal government.[22]

The Civil War era showed the extent of Southern influence on Indiana. Much of southern and central Indiana had strong ties to the South. Many of the region's early settlers had come from the Confederate state of Virginia and from Kentucky. Governor Morton wrote to President Lincoln that no other free state was so populated with southerners, and they kept Morton from being as forceful against secession as he wanted to be.[23]

Indiana Senator Jesse D. Bright had been a leader among the Indiana Democratic Party for several years prior to the outbreak of the war. In 1862, Bright was expelled from the United States Senate on allegations of disloyalty. He had written a letter to "His Excellency, Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederation", in which Bright offered the services of a friend to sell the South firearms. As of 2011, he was the last senator to be expelled from the Senate.[24] Bright was replaced with a pro-Union Democrat, former governor Joseph A. Wright.[25]

Conflict with the Democrats

On April 21, 1861, Morton called a special session of the Indiana General Assembly to allow him to raise additional regiments for service in the Union Army. Initially the legislature, which was controlled by the Democratic Party, was supportive of his measures and passed the legislation Morton requested.[26] After the legislature adjourned in May, the Indiana Daily Sentinel newspaper and some prominent Democrats in the state changed their opinion of the war. The Sentinel ran anti-war articles, including one entitled "Let Them Go In Peace". The Democratic position was clarified at a state convention in the summer of 1862. The convention was chaired by Thomas Hendricks, and convention members stated that they supported the integrity of the Union and the war effort but opposed the abolition of slavery.[27]

During 1862, Morton never called the Indiana General Assembly into session. Morton feared the legislature's Democratic majority would attempt to hinder the war effort and could vote to secede from the Union. Republican legislators stay away from the capitol to prevent the General Assembly from attaining the quorum needed for the body to act. No budget or tax provisions were passed. This rapidly led to a crisis as Indiana ran out of money to conduct business, and the state was on the edge of bankruptcy. Going beyond his constitutional powers, Morton solicited millions of dollars in private loans. His move was successful, and Morton was able privately to fund the state government and the war effort in Indiana. Morton urged pro-war Democrats to abandon their party in the name of unity for the duration of the war.[28] In one notorious incident, Morton had soldiers disrupt a Democratic state convention in an incident that would latter be referred to as the Battle of Pogue's Run.[29]

Indiana's political polarity worsened after the Emancipation Proclamation made freeing the slaves a war goal in 1863. Many of the formerly pro-war Democrats moved to openly oppose the war. The same year, Morton began a crackdown on dissidents.[30] While most of the state was decidedly pro-Union, a group of Southern sympathizers known as the Sons of the Golden Circle had a strong presence in northern Indiana. This group proved enough of a threat that General Lew Wallace, commander of Union forces in the region, had to spend considerable time countering their activities. By June 1863, the group was successfully broken up by Wallace and Morton. Many Golden Circle members were arrested without formal charges, the pro-Confederate press was prevented from printing anti-war material, and the writ of habeas corpus was denied to anyone suspected of disloyalty. Confederate special agent Thomas Hines went to French Lick in June 1863, seeking support for Confederate General John Hunt Morgan's eventual raid into Indiana. Hines met with Sons of Liberty "major general" William A. Bowles, inquiring if Bowles could offer any support for Morgan's upcoming raid. Bowles told Hines he could raise a force of 10,000, but before the deal was finalized, Hines was told a Union force was approaching, causing him to flee. As a result, there would be no support for Morgan's Raid by Bowles, which caused Morgan to treat harshly anyone in Indiana who claimed to be sympathetic to the Confederacy.[31]

In reaction to his actions cracking down on dissent, the Indiana Democratic Party called Morton a "Dictator" and an "Underhanded Mobster" while Republicans countered that the Democrats were using treasonable and obstructionist tactics in the conduct of the war.[32] Large-scale support for the Confederacy among Golden Circle members and Southern Hoosiers in general fell away after Morgan's Raid, when Confederate raiders ransacked many homes bearing the banners of the Golden Circle despite their proclaimed support for the Confederates. After that, said Confederate Colonel Basil W. Duke, "The Copperheads and Vallandighammers fought harder than the others" against Morgan's Raiders.[33] When Hoosiers failed to rise in large numbers in support of Morgan's Raid, Morton slowed his crackdown on Confederate sympathizers, theorizing that because they had failed to come to Morgan's aid in large numbers, they would similarly fail to come to the aid of a larger invasion.[34]

Smuggling into Confederate territory was common in the early days of the war, when the Union Army had not yet pushed the front lines far to the south of the Ohio River. The towns of New Albany and Jeffersonville were pressured by the Cincinnati Daily Gazette to stop trading with the South, especially with Louisville, as Kentucky's proclaimed neutrality was perceived as Southern-leaning. A fraudulent steamboat company was set up to go between Madison and Louisville, with its boat, the Masonic Gem, making regular trips to Confederate ports for trade. Throughout the war, New Albany and Jeffersonville were the origin of many Northern goods smuggled into the Confederacy.[35]

Southern sympathizers

While not particularly numerous, some Hoosiers chose to fight for the South. Most traveled to Kentucky to join Confederate regiments formed in that state. Sgt. Henry L. Stone of Greencastle rode with John Hunt Morgan when he raided Indiana. The exact number of Hoosiers to serve in Confederate armies is unknown, but there are numerous references to such men.[36] Former U.S. Army officer Francis A. Shoup briefly led the Indianapolis Zouave militia, but left for Florida prior to the start of the war and ultimately become a Confederate Brigadier General.[10]

Republican takeover

For the loans needed to run the state during the long period of no legislative support, Morton turned to James Lanier, a wealthy banker from Madison, Indiana. On two occasions, Lanier loaned the state more than $1 million (USD) without security. When the Republican Party gained a legislative majority in 1864, he was paid back and the grateful state preserved his Madison residence as a historic site.[4] Without Lanier's support the government would certainly have bankrupted and hurt the Union war effort. There was little the legislature could do but watch as the Governor ran the state with private financing, as Morton had the Republican legislators leave Indianapolis for Madison, to prevent a quorum.[37]

The 1864 Republican legislative majority came at a critical turning point in the war, as the North was slowly tightening the blockade of the South. The new legislature fully supported Morton's policies and worked to meet the state's commitments to the war effort. It validated the loans Morton had taken to run the state, assumed them as state debt, and commended Morton for his actions in the interim.[4] Later in the year Lincoln again won the state of Indiana's electoral votes, winning 53.6% to George McClellan's 46.4%.[38]

Aftermath

News of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's surrender reached Indianapolis at 11 p.m. on April 9, 1865.[39] The Indianapolis Journal called the subsequent celebrations within the city "demented".[39] The celebrations ceased after news of the assassination of Lincoln arrived on April 15. Lincoln's funeral train passed through the capital city on April 30, and 100,000 people attended his bier at the Indiana State House.[39]

Economic

The Civil War forever altered Indiana's economy. Before the war, New Albany was the largest city in the state, primarily due to its commerce with the South. More than 50% of the wealthiest Hoosiers had lived in New Albany at the start of the war.[40] Trade with the South dwindled during the war, and after the war much of Indiana saw New Albany as too friendly to the South.[41] New Albany's formerly robust industry building steamboats for Southern trade ended in 1870. The last steamboat built in New Albany was named the Robert E. Lee. The city never regained its pre-war stature, the population leveling at 40,000 people, and only its antebellum, early-Victorian Mansion-Row remains from its boom period.[41]

The war caused Indiana's industry to grow exponentially. The shift in population to the central and northern portions of the state was accelerated as new industry and cities began to develop around the Great Lakes and the railroad depots created during the war. Colonel Eli Lilly after the war founded Eli Lilly and Company which grew into the state's largest corporation. Charles Conn, another war veteran, founded C.G. Conn Ltd. in Elkhart which gave rise to a new industry there, building musical instruments. Indianapolis was also the wartime home of Doctor Richard Gatling; there he invented the Gatling Gun, one of the world's first machine guns, but it was not officially approved by the United States government until after the war.[42] In contrast to the growing industrial power of central and northern Indiana, Southern Indiana remained largely agricultural for another 40 years.

Political

When the war ended, the state's Democrats were upset over their treatment during the war. The Democratic Party in Indiana staged a quick comeback, and Indiana became the first state after the Civil War to elect a Democratic governor. Thomas Hendricks' rise to office initiated a period of Democratic control that reversed many of the political gains made by the Republican Party during the war.[43]

Indiana's Senators were strong supporters of the radical Reconstruction plans proposed by Congress. Both Oliver Morton (who was elected to the Senate after his term as governor) and Senator Schuyler Colfax voted in favor of the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson. Morton was especially disappointed in Congress' failure to remove him.[44]

When the South came back under firm Democratic control at the end of the 1870s, Indiana, which was closely split between the parties, became a key swing state that often decided the balance of power in Congress and the Presidency. Almost every presidential election between the Civil War and World War I included one or more Hoosiers as national political parties tried to win the support of Indiana's electorate. In 1888, while at the height of the state's post-war political influence, General Benjamin Harrison was elected President, the first Hoosier to assume the office.

Social

More than half the state's households contributed one or more members to fight in the war.[2] This made the effects of the conflict widely felt throughout the state. After the war, veterans programs were initiated to help wounded soldiers with housing, food, and other basic needs. Orphanages and asylums were established to help the wives and children of the war dead. In terms of the war dead, more Hoosiers died in the Civil War than in any other conflict. Although twice as many men were mustered in World War II, more than twice as many Hoosiers died in the Civil War.[45]

Women had been especially active in supporting the war on the home front, and many used their organizational skills to promote prohibition through the WCTU and woman suffrage. Zerelda Wallace, the stepmother of General Lew Wallace, founded the Indiana chapter of the WCTU. Suffrage legislation was introduced in the Indiana General Assembly during the term of Governor Thomas Hendricks, but the bill was defeated.[46][47]

The Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument in downtown Indianapolis was built to honor the Indiana veterans of the Civil War. The construction began in 1888 after two decades of discussion and was finally completed in 1901.[48]

See also

Notes

- ↑ John D. Barnhart, "The Impact of the Civil War on Indiana," Indiana Magazine of History (1961) 57#3 pp. 185-224 online

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Barhhart, "The Impact of the Civil War on Indiana," pp. 185-224

- ↑ "United States Census of 1860" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. p. 2. Retrieved 2008-10-15.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Northern Indiana Historical Society. "Indiana History Chapter Five". Indiana Center for History. Archived from the original on March 11, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "Indiana in the Civil War". Civil War Indiana.com. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "The Impact of the Civil War on Indiana," pp. 185-224

- ↑ Funk (1967) p.6

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Funk (1969) pp.218–220

- ↑ "Indiana's Prominent Civil War Personalities". Civil War Indiana. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved 2009-04-20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bodenhamer p.441

- ↑ Roger Pickenpaugh, Captives in Gray: The Civil War Prisons of the Union (2009)

- ↑ David Eicher, The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (2002) pp 310-311.

- ↑ Horan pp.24–25

- ↑ David L. Mowery, and Douglas W. Bostick, Morgan's Great Raid: The Remarkable Expedition from Kentucky to Ohio (2013) ch 3

- ↑ Mowery and Bostick, Morgan's Great Raid (2013) pp 81-82

- ↑ Alan D. Gaff, On Many a Bloody Field: Four Years In The Iron Brigade (Indiana University Press, 1996)

- ↑ Terrell, Indiana in the war of the Rebellion (1869) pp 561-77

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Bodenhamer p.442

- ↑ "Fact Sheet". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

- ↑ Leip, Dave. "1860 Presidential General Election Results – Indiana". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ Kramer pp.164–165, 168

- ↑ Foulke p.155

- ↑ Sharp p. 94

- ↑ "Friendship or Treason?". United States Senate. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ↑ James Albert Woodburn (1903). Party politics in Indiana during the civil war. American Historical Association. p. 231.

- ↑ Stampp (1949) ch 5

- ↑ Thomas E. Rodgers, "Liberty, Will, and Violence: The Political Ideology of the Democrats of West-Central Indiana during the Civil War," Indiana Magazine of History (1996) 92#2 pp. 133-159 in JSTOR

- ↑ Kenneth M. Stampp, Indiana Politics during the Civil War (1949) ch 6

- ↑ Bodenhamer pp. 441–443

- ↑ Stampp (1949) ch 10

- ↑ Horan pp.25–27

- ↑ David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. pp. 444–45. ISBN 978-0-253-11249-1.

- ↑ James Ford Rhodes (1906). History of the United States from the compromise of 1850 to the end of the Roosevelt administration. Macmillan. p. 316.

- ↑ Rhodes p.317

- ↑ E. Merton Coulter, Confederate States of America, 1861-1865 (1950) pp.295–96

- ↑ Holliday p.29

- ↑ Bodenhamer p.1023

- ↑ Leip, Dave. "1864 Presidential General Election Results – Indiana". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Bodenhamer p.443

- ↑ Miller H. p.48

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Findling p.53

- ↑ Farwell p.345

- ↑ Stampp (1949) ch 7

- ↑ Morton pp.54–55

- ↑ Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era: 1850-1880 (1965) pp 580-81

- ↑ Rosemary Skinner Keller et al. (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Religion in North America: Women and religion: methods of study and reflection. Indiana University Press. p. 303.

- ↑ Thornbrough, Indiana in the Civil War Era: 1850-1880 (1965) pp 258-61

- ↑ Bodenhamer p.1278

References

- Barnhart, John D. "The Impact of the Civil War on Indiana," Indiana Magazine of History (1961) 57#3 pp. 185–224 in JSTOR

- Baxter, Nancy Niblack (1995). Gallant Fourteenth: The Story of an Indiana Civil War Regiment. Emmis Books. ISBN 0-9617367-8-X.

- Bodenhamer, David (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- Findling, John (2003). A History of New Albany, Indiana. Indiana University Southeast.

- Foulke, William D. (1899). Life of Oliver P. Morton. Bowen-Merrill Company.

- Funk, Arville L (1967). Hoosiers In The Civil War. Chicago: Adams Press. ISBN 0-9623292-5-8.

- Funk, Arville L (1983) [1969]. A Sketchbook of Indiana History. Rochester, Indiana: Christian Book Press.

- Holliday, John. (1911). Indianapolis and the Civil War. E. J. Hecker.

- Horan, James D. (1954). Confederate Agent: A Discovery in History. Crown Publishers.

- Kramer, Carl (2007). This Place We Call Home. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34850-0.

- Nation, Richard F. "Violence and the Rights of African Americans in Civil War-Era Indiana," Indiana Magazine of History (2004) 100#3 pp 215–230, online

- Nelson, Jacquelyn S. "The Military Response of the Society of Friends in Indiana to the Civil War," Indiana Magazine of History (1985) 81#2 pp 101–130, on Quakers; online

- Rodgers, Thomas E. "Hoosier Women and the Civil War Home Front," Indiana Magazine of History (2001) 97#2 pp 105–128 online

- Sharp, Walter Rice. "Henry S. Lane and the Formation of the Republican Party in Indiana," Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1920) 7#2 pp. 93–112 in JSTOR

- Stampp, Kenneth M. Indiana politics during the Civil War (1949); monograph by leading scholar

- Thornbrough, Emma Lou. Indiana in the Civil War Era, 1850-1880 (1965); the standard scholarly history

- Towne, Stephen E. "Killing the Serpent Speedily: Governor Morton, General Hascall, and the Suppression of the Democratic Press in Indiana, 1863," Civil War History (2006) 52#1 pp 41–65.

Historiography

- Towne, Stephen E. "Tending the Soil," Ohio Valley History (Summer 2011), 11#2 pp 41–55; scholarship published since 1999

Primary sources

- Nation, Richard F., and Stephen E. Towne. Indiana's War: The Civil War in Documents (2009), primary sources excerpt and text search

- Terrell, W.H.H. Indiana in the War of the Rebellion. Report of the Adjutant General (1969), reprinted by Indiana Historical Collections Volume XLI (1960)

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||