Indian independence movement

|

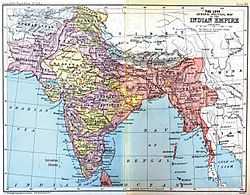

Imperial entities of India | |

| Dutch India | 1605–1825 |

|---|---|

| Danish India | 1620–1869 |

| French India | 1769–1954 |

| Casa da Índia | 1434–1833 |

| Portuguese East India Company | 1628–1633 |

| East India Company | 1612–1757 |

| Company rule in India | 1757–1858 |

| British Raj | 1858–1947 |

| British rule in Burma | 1824–1948 |

| Princely states | 1721–1949 |

| Partition of India |

1947 |

The term Indian Independence Movement encompasses activities and ideas aiming to end first East India Company rule (1757–1858), then the British Raj (1858–1947). The independence movement saw various national and regional campaigns, agitations and efforts, some nonviolent and others not so.

The first organized militant movements were in Bengal, but they later took to the political stage in the form of a mainstream movement in the then newly formed Indian National Congress (INC), with prominent moderate leaders seeking only their basic right to appear for Indian Civil Service examinations, as well as more rights, economic in nature, for the people of the soil. The early part of the 20th century saw a more radical approach towards political independence proposed by leaders such as the Lal, Bal, Pal and Aurobindo Ghosh.

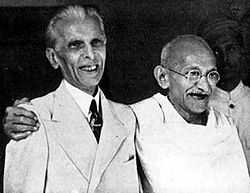

The last stages of the independence struggle from the 1920s onwards saw Congress adopt Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi's policy of nonviolence and civil resistance, Muhammad Ali Jinnah's constitutional struggle for the rights of minorities in India, and several other campaigns. Revolutionaries such as Subhas Chandra Bose and Bhagat Singh preached armed revolution to achieve independence. Poets & writers such as Allama Iqbal, Mohammad Ali Jouhar, Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul Islam used literature, poetry and speech as a tool for political awareness. Feminists such as Sarojini Naidu and Begum Rokeya championed the emancipation of Indian women and their participation in national politics. Babasaheb Ambedkar championed the cause of the disadvantaged sections of Indian society within the larger independence movement. The period of the Second World War saw the peak of the campaigns by the Quit India movement (led by Mahatma Gandhi) and the Indian National Army (INA) movement (led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose) and others, eventually resulting in the withdrawal of the British.

The work of these various movements led ultimately to the Indian Independence Act 1947, which created the independent dominions of India and Pakistan. India remained a Dominion of the Crown until 26 January 1950, when the Constitution of India came into force, establishing the Republic of India; Pakistan was a dominion until 1956, when it adopted its first republican constitution. In 1971, East Pakistan declared independence as the People's Republic of Bangladesh.

The Indian independence movement was a mass-based movement that encompassed various sections of society. It also underwent a process of constant ideological evolution.[1] Although the basic ideology of the movement was anti-colonial, it was supported by a vision of independent capitalist economic development coupled with a secular, democratic, republican, and civil-libertarian political structure.[2] After the 1930s, the movement took on a strong socialist orientation, due to the increasing influence of left-wing elements in the INC as well as the rise and growth of the Communist Party of India.[1] The All-India Muslim League was formed in 1906 as a separate Muslim party which later in 1940 called for separate state of Pakistan.

Background (1757–1883)

Early British colonialism in India

European traders first reached Indian shores with the arrival of the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama in 1498 AD at the port of Calicut, in search of the lucrative spice trade. Just over a century later, the Dutch and English established trading outposts on the subcontinent, with the first English trading post set up at Surat in 1612.[3] Over the course of the 17th and early 19th centuries, the British[4] defeated the Portuguese and Dutch militarily, but remained in conflict with the French, who had by then sought to establish themselves in the subcontinent. The decline of the Mughal empire in the first half of the 18th century provided the British with the opportunity to seize a firm foothold in Indian politics.[5] After the Battle of Plassey in 1757 AD, during which the East India Company's Indian army under Robert Clive defeated Siraj-ud-Daula, the Nawab of Bengal, the Company established itself as a major player in Indian affairs, and soon afterwards gained administrative rights over the regions of Bengal, Bihar and Midnapur part of Odissa, following the Battle of Buxar in 1764.[6] After the defeat of Tipu Sultan, most of South India came either under the Company's direct rule, or under its indirect political control as part a princely state in a subsidiary alliance. The Company subsequently gained control of regions ruled by the Maratha Empire, after defeating them in a series of wars. Punjab was annexed in 1849, after the defeat of the Sikh armies in the First (1845–1846) and Second (1848–49) Anglo-Sikh Wars.

In 1835, English was made the medium of instruction in India's schools. Western-educated Hindu elites sought to rid Hinduism of controversial social practices, including the varna caste system, child marriage, and sati. Literary and debating societies established in Calcutta (Kolkata) and Bombay (Mumbai) became forums for open political discourse.

Even while these modernising trends influenced Indian society, many Indians increasingly disliked British rule. With the British now dominating most of the subcontinent, many Brits increasingly disregarded local customs by, for example, staging parties in mosques, dancing to the music of regimental bands on the terrace of the Taj Mahal, using whips to force their way through crowded bazaars (as recounted by General Henry Blake), and mistreating Indians (including the sepoys). In the years after the annexation of Punjab in 1849, several mutinies broke out among the sepoys; these were put down by force.

First rebellion of India against British

Pazhassi Raja (eighteenth century)

Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja (also known as Cotiote Rajah or Pychy Rajah) (3 January 1753 – 30 November 1805) was one of the earliest freedom fighters in India. He was the prince regent of the princely state of Kottayam or Cotiote in Malabar, India between 1774 and 1805. His struggles with English East India Company is known as The Cotiote War. He is popularly known as Kerala Simham (Lion of Kerala) on account of his martial exploits.

Veerapandiya Kattabomman (eighteenth century)

The Indian independence movement had a long history in the Tamil-speaking districts of the then Madras Presidency going back to the 18th century. The first resistance to the British was offered by the legendary Puli Thevan in 1757. Since then there had been rebellions by polygars such as the Mamannar Marudu brothers, Veerapandiya Kattabomman, Oomathurai and Dheeran Chinnamalai.

Veerapandiya Kattabomma Karuthayya Nayakkar (also known as Kattabomman) was a courageous 18th-century Palayakarrar ('Polygar') chieftain from Panchalankurichi of Tamil Nadu, India. His ancestors migrated to Tamil Nadu from Kandukur area of Prakasam district in present day Andhra Pradesh during the Vijayanagara period. Also known as Kattabomma Nayakkar he was among the earliest to oppose British rule in these regions. He waged a war with the British six decades before the Indian War of Independence occurred in the Northern parts of India. He was captured and hanged in 1799 CE. His fort was destroyed and his wealth was looted by the British army. Today his native village Panchalankurichi in present day Thoothukudi district of Tamil Nadu is a historically important site.[1] Some polygars families also migrated to vedal village in Kanchipuram District, India.

Paika Bidroha / Paik Rebellion (1817 )

In September 1804 the King of Khurda, Kalinga, was deprived of the traditional rights of Jagannath Temple which was a serious shock to the King and the people of Odisha. Consequently in October 1804 a group of armed Paiks attacked the British at Pipili. This event alarmed the British force. Jayee Rajguru the chief of Army of Kalinga, requested all the Kings of the State to join hands for a common cause against the British. The Kings of Kujanga, Kanika, Harishpur, Marichipur and others made an alliance with the King of Khurda and prepared themselves for the battle. Jayee Rajguru was later hailed as the first martyr of India against Britain.[7] Jayee Rajguru was killed on 6 December 1806 in a procedure in which executioners tied his legs to the opposite bounded branches of a tree and released the branch .[8] But the rebellion had not stopped and Bakshi Jagabandhu commanded an armed rebellion against the British East India Company's rule in Odisha which is known as Paik Rebellion.

Paik Rebellion gave the nation the first direction towards the war for Independence. In 1817 with the leadership of Bakshi Jagabandhu . the landed militiants of Odisha to whom the English conquest had brought little but ruin and oppression. Brave and undaunted as the Paikas were in comparison to the British Sepoys, the nature of the country and their intimate knowledge of it gave them an advantage which rendered the contest very severe.

The Paiks were the traditional landed militia of Odisha. They served as warriors and were charged with policing functions during peacetime. The Paiks were organised into three ranks distinguished by their occupation and the weapons they wielded. These were the Paharis, the bearers of shields and the khanda sword, the Banuas who led distant expeditions and used matchlocks and the Dhenkiyas - archers who also performed different duties in Odisha armies.[9] With the conquest of Odisha by the East India Company in 1803 and the dethronement of the Raja of Khurda began the fall of the power and prestige of the Paiks. The attitude of the company to the Paiks was expressed by Walter Ewer, on the commission that looked into the causes of the Rebellion, thus: "Now there is no need of assistance of Paiks at Khurda. It is dangerous to keep them in British armed forces. Thus they should be treated and dealt as common Ryots and land revenue and other taxes should be collected from them. They must be deprived of their former Jagir lands (rent free lands given to the Paiks for their military service to the state.) Within a short period of time the name of Paik has already been forgotten. But still now where the Paiks are living they have retained their previous aggressive nature. In order to break their poisonous teeth the British Police must be highly alert to keep the Paiks under their control for a pretty long period, unless the Paik community is ruined completely the British rule cannot run smoothly."[10]

Discontent over the policies of the company was simmering in Odisha when, in March 1817, a 400-strong party of Kandhas crossed over into Khurda from the State of Ghumsur, openly declaring their rebellion against the company's rule. The Paiks under Jagbandhu joined them, looting and setting to fire the police station and post office at Banpur. The rebels then marched to Khurda itself, which the company abandoned, sacking the civil buildings and the treasury there. Another body of rebels captured Paragana Lembai, where they killed native officials of the company.[10][11]

The company government, led by E. Impey, the magistrate at Cuttack, dispatched forces to quell the rebellion under Lieutenant Prideaure to Khurda and Lieutenant Faris to Pipli in the beginning of April. These met with sustained attacks from the Paiks, forcing them to retreat to Cuttack, suffering heavy losses, and Faris himself was killed by the Paiks. Another force sent to Puri under Captain Wellington, however, faced little opposition, and on 9 April a force of 550 men was sent to Khurda. Three days later they took Khurda and declared martial law in the Khurda territory.[10][11]

Even as the British managed to wrest control of Khurda, Puri itself fell to the insurgents led by Bakshi Jagabandhu, and the British were forced to retreat to Cuttack by 18 April. Cuttack remained cut off from the now rebel-held portions of southern Odisha, and therefore the British remained unaware of the fate of the force they had dispatched to Khurda. The force's successes in Khurda allowed the commanding officer, Captain Le Fevere, to pursue the insurgents into Puri. This British party defeated a thousand-strong but ill-equipped force of the Paiks as they marched to Puri, and they retook Puri and captured the Raja before he could escape from the town.[10][11]

The uprising spread rapidly across Odisha, and there were several encounters between the British and Paik forces, including at Cuttack, where the latter were quickly put down. By May 1817, the British managed to re-establish their authority over the entire province, but it was a long while before the tranquillity finally returned to it.[10][11]

Vellore sepoy mutiny

The garrison of the Vellore Fort in July 1806 comprised four companies of British infantry from H.M. 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot and three battalions of Madras infantry.

Two hours after midnight, on 10 July, the sepoys in the fort shot down the European sentries and killed fourteen of their own officers and 115 men of the 69th Regiment, most of the latter as they slept in their barracks. Among those killed was Colonel St. John Fancourt, the commander of the fort. The rebels seized control by dawn, and raised the flag of the Mysore Sultanate over the fort. Tipu's second son Fateh Hyder was declared King.

However a British officer escaped and alerted the garrison in Arcot. Nine hours after the outbreak of the mutiny, a relief force comprising the British 19th Light Dragoons, galloper guns and a squadron of Madras cavalry, rode from Arcot to Vellore, covering 16 miles in about two hours. It was led by Sir Rollo Gillespie – one of the most capable and energetic officers in India at that time – who reportedly left Arcot within a quarter of an hour of the alarm being raised. Gillespie dashed ahead of the main force with a single troop of about 20 men.

Arriving at Vellore Gillespie found the surviving Europeans, about sixty men of the 69th, commanded by NCOs and two assistant surgeons, still holding part of the ramparts but out of ammunition. Unable to gain entry through the defended gate, Gillespie climbed the wall with the aid of a rope and a sergeant's sash which was lowered to him; and to gain time led the 69th in a bayonet-charge along the ramparts. When the rest of the 19th arrived, Gillespie had them blow the gates with their galloper guns, and made a second charge with the 69th to clear a space inside the gate to permit the cavalry to deploy. The 19th and the Madras Cavalry then charged and slaughtered any sepoy who stood in their way. About 100 sepoys who had sought refuge in the palace were brought out, and by Gillespie's order, placed against a wall and shot dead. John Blakiston, the engineer who had blown in the gates, recalled: "Even this appalling sight I could look upon, I may almost say, with composure. It was an act of summary justice, and in every respect a most proper one; yet, at this distance of time, I find it a difficult matter to approve the deed, or to account for the feeling under which I then viewed it.

The harsh retribution meted out to the sepoys snuffed out the unrest at a stroke and provided the history of the British in India with one of its true epics; for as Gillespie admitted, with a delay of even five minutes, all would have been lost. In all, nearly 350 of the rebels were killed, and another 350 wounded before the fighting had stopped.

The rebellion of 1857 and its consequences

The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a large-scale rebellion in northern and central India against the British East India Company's rule. It was suppressed and the British government took control of the company.

The conditions of service in the company's army and cantonments increasingly came into conflict with the religious beliefs and prejudices of the sepoys.[12] The predominance of members from the upper castes in the army, perceived loss of caste due to overseas travel, and rumours of secret designs of the government to convert them to Christianity led to deep discontentment among the sepoys.[13] The sepoys were also disillusioned by their low salaries and the racial discrimination practised by British officers in matters of promotion and privileges.[13] The indifference of the British towards leading native Indian rulers such as the Mughals and ex-Peshwas and the annexation of Oudh were political factors triggering dissent amongst Indians. The Marquess of Dalhousie's policy of annexation, the doctrine of lapse (or escheat) applied by the British, and the projected removal of the descendants of the Great Mughal from their ancestral palace at Red Fort to the Qutb (near Delhi) also angered some people.

The final spark was provided by the rumoured use of tallow (from cows) and lard (pig fat) in the newly introduced Pattern 1853 Enfield rifle cartridges. Soldiers had to bite the cartridges with their teeth before loading them into their rifles, and the reported presence of cow and pig fat was religiously offensive to both Hindu and Muslim soldiers.[14]

Mangal Pandey, a 29-year old sepoy, was believed to be responsible for inspiring the Indian sepoys to rise against the British. In the first week of May 1857, he killed a higher officer in his regiment at Barrackpore for the introduction of the offensive rule. He was captured and was sentenced to death when the British took back control over the regiment. On 10 May 1857, the sepoys at Meerut broke rank and turned on their commanding officers, killing some of them. They then reached Delhi on 11 May, set the company's toll house afire, and marched into the Red Fort, where they asked the Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, to become their leader and reclaim his throne. The emperor was reluctant at first, but eventually agreed and was proclaimed Shehenshah-e-Hindustan by the rebels.[15] The rebels also murdered much of the European, Eurasian, and Christian population of the city.[16]

Revolts broke out in other parts of Oudh and the North-Western Provinces as well, where civil rebellion followed the mutinies, leading to popular uprisings.[17] The British were initially caught off-guard and were thus slow to react, but eventually responded with force. The lack of effective organisation among the rebels, coupled with the military superiority of the British, brought a rapid end to the rebellion.[18] The British fought the main army of the rebels near Delhi, and after prolonged fighting and a siege, defeated them and retook the city on 20 September 1857.[19] Subsequently, revolts in other centres were also crushed. The last significant battle was fought in Gwalior on 17 June 1858, during which Rani Lakshmibai was killed. Sporadic fighting and guerrilla warfare, led by Tatya Tope, continued until spring 1859, but most of the rebels were eventually subdued.

The Indian Rebellion of 1857 was a major turning point in the history of modern India. While affirming the military and political power of the British,[20] it led to significant change in how India was to be controlled by them. Under the Government of India Act 1858, the Company was deprived of its involvement in ruling India, with its territory being transferred to the direct authority of the British government.[21] At the apex of the new system was a Cabinet minister, the Secretary of State for India, who was to be formally advised by a statutory council;[22] the Governor-General of India (Viceroy) was made responsible to him, while he in turn was responsible to the government. In a royal proclamation made to the people of India, Queen Victoria promised equal opportunity of public service under British law, and also pledged to respect the rights of the native princes.[23] The British stopped the policy of seizing land from the princes, decreed religious tolerance and began to admit Indians into the civil service (albeit mainly as subordinates). However, they also increased the number of British soldiers in relation to native Indian ones, and only allowed British soldiers to handle artillery. Bahadur Shah was exiled to Rangoon, Burma, where he died in 1862.

In 1876, in a controversial move Prime Minister Disraeli acceded to the Queen's request and passed legislation to give Queen Victoria the additional title of Empress of India. Liberals in Britain objected that the title was foreign to British traditions.[24]

Rise of organized movements

The decades following the Rebellion were a period of growing political awareness, manifestation of Indian public opinion and emergence of Indian leadership at both national and provincial levels. Dadabhai Naoroji formed the East India Association in 1867 and Surendranath Banerjee founded the Indian National Association in 1876.

Inspired by a suggestion made by A.O. Hume, a retired British civil servant, seventy-three Indian delegates met in Bombay in 1885 and founded the Indian National Congress. They were mostly members of the upwardly mobile and successful western-educated provincial elites, engaged in professions such as law, teaching and journalism. At its inception, the Congress had no well-defined ideology and commanded few of the resources essential to a political organisation. Instead, it functioned more as a debating society that met annually to express its loyalty to the British Raj and passed numerous resolutions on less controversial issues such as civil rights or opportunities in government (especially in the civil service). These resolutions were submitted to the Viceroy's government and occasionally to the British Parliament, but the Congress's early gains were srit. Despite its claim to represent all India, the Congress voiced the interests of urban elites; the number of participants from other social and economic backgrounds remained negligible.

The influence of socio-religious groups such as Arya Samaj (started by Swami Dayanand Saraswati) and Brahmo Samaj (founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and others) became evident in pioneering reforms of Indian society. The work of men like Swami Vivekananda, Ramakrishna Paramhansa, Sri Aurobindo, V. O. Chidambaram Pillai Subramanya Bharathy, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Rabindranath Tagore and Dadabhai Naoroji, as well as women such as the Scots–Irish Sister Nivedita, spread the passion for rejuvenation and freedom. The rediscovery of India's indigenous history by several European and Indian scholars also fed into the rise of nationalism among Indians.

Rise of Indian nationalism (1885–1905)

By 1900, although the Congress had emerged as an all-India political organisation, its achievement was undermined by its singular failure to attract Muslims, who felt that their representation in government service was inadequate. Attacks by Hindu reformers against religious conversion, cow slaughter, and the preservation of Urdu in Arabic script deepened their concerns of minority status and denial of rights if the Congress alone were to represent the people of India. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan launched a movement for Muslim regeneration that culminated in the founding in 1875 of the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh (renamed Aligarh Muslim University in 1920). Its objective was to educate wealthy students by emphasising the compatibility of Islam with modern western knowledge. The diversity among India's Muslims, however, made it impossible to bring about uniform cultural and intellectual regeneration.

The nationalistic sentiments among Congress members led to the movement to be represented in the bodies of government, to have a say in the legislation and administration of India. Congressmen saw themselves as loyalists, but wanted an active role in governing their own country, albeit as part of the Empire. This trend was personified by Dadabhai Naoroji, who went as far as contesting, successfully, an election to the British House of Commons, becoming its first Indian member.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was the first Indian nationalist to embrace Swaraj as the destiny of the nation. Tilak deeply opposed the then British education system that ignored and defamed India's culture, history and values. He resented the denial of freedom of expression for nationalists, and the lack of any voice or role for ordinary Indians in the affairs of their nation. For these reasons, he considered Swaraj as the natural and only solution. His popular sentence "Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it" became the source of inspiration for Indians.

In 1907, the Congress was split into two factions: The radicals, led by Tilak, advocated civil agitation and direct revolution to overthrow the British Empire and the abandonment of all things British. The moderates, led by leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, on the other hand wanted reform within the framework of British rule. Tilak was backed by rising public leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal and Lala Lajpat Rai, who held the same point of view. Under them, India's three great states – Maharashtra, Bengal and Punjab shaped the demand of the people and India's nationalism. Gokhale criticised Tilak for encouraging acts of violence and disorder. But the Congress of 1906 did not have public membership, and thus Tilak and his supporters were forced to leave the party.

But with Tilak's arrest, all hopes for an Indian offensive were stalled. The Congress lost credit with the people. A Muslim deputation met with the Viceroy, Minto (1905–10), seeking concessions from the impending constitutional reforms, including special considerations in government service and electorates. The British recognised some of the Muslim League's petitions by increasing the number of elective offices reserved for Muslims in the Indian Councils Act 1909. The Muslim League insisted on its separateness from the Hindu-dominated Congress, as the voice of a "nation within a nation".

Partition of Bengal, 1905

In July 1905, Lord Curzon, the Viceroy and Governor-General (1899–1905), ordered the partition of the province of Bengal supposedly for improvements in administrative efficiency in the huge and populous region.[25] It also had justifications due to increasing conflicts between Muslims and dominant Hindu regimes in Bengal. However, the Indians viewed the partition as an attempt by the British to disrupt the growing national movement in Bengal and divide the Hindus and Muslims of the region. The Bengali Hindu intelligentsia exerted considerable influence on local and national politics. The partition outraged Bengalis. Not only had the government failed to consult Indian public opinion, but the action appeared to reflect the British resolve to divide and rule. Widespread agitation ensued in the streets and in the press, and the Congress advocated boycotting British products under the banner of swadeshi. Hindus showed unity by tying Rakhi on each other's wrists and observing Arandhan (not cooking any food). During this time, Bengali Hindu nationalists begin writing virulent newspaper articles and were charged with sedition. Brahmabhandav Upadhyay, a Hindu newspaper editor who helped Tagore establish his school at Shantiniketan, was imprisoned and the first martyr to die in British custody in the 20th century struggle for independence.

All India Muslim League

The All India Muslim League was founded by the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference at Dhaka (now Bangladesh), in 1906, in the context of the circumstances that were generated over the partition of Bengal in 1905. Being a political party to secure the interests of the Muslim diaspora in British India, the Muslim League played a decisive role during the 1940s in the Indian independence movement and developed into the driving force behind the creation of Pakistan in the Indian subcontinent.But when Muslim league passed Pakistan resolution based on Two Nation theory of Jinnah, Nationalist leaders like Maulana Azad and others stood against it. All-India Jamhur Muslim League was formed parallel to Muslim League with Raja of Mahmoodabad (a close associate of Jinnah) as its president and Dr.Maghfoor Ahmad Ajazi its general secretary.[26]

In 1906, Muhammad Ali Jinnah joined the Indian National Congress, which was the largest Indian political organization. Like most of the Congress at the time, Jinnah did not favour outright independence, considering British influences on education, law, culture and industry as beneficial to India. Jinnah became a member on the sixty-member Imperial Legislative Council. The council had no real power or authority, and included a large number of un-elected pro-Raj loyalists and Europeans. Nevertheless, Jinnah was instrumental in the passing of the Child Marriages Restraint Act, the legitimization of the Muslim waqf (religious endowments) and was appointed to the Sandhurst committee, which helped establish the Indian Military Academy at Dehra Dun.[27] During the First World War, Jinnah joined other Indian moderates in supporting the British war effort, hoping that Indians would be rewarded with political freedoms.

First World War

The First World War began with an unprecedented outpouring of support towards Britain from within the mainstream political leadership, contrary to initial British fears of an Indian revolt. India contributed massively to the British war effort by providing men and resources. About 1.3 million Indian soldiers and labourers served in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, while both the Indian government and the princes sent large supplies of food, money and ammunition. However, Bengal and Punjab remained hotbeds of anti colonial activities. Nationalism in Bengal, increasingly closely linked with the unrests in Punjab, was significant enough to nearly paralyse the regional administration.[28][29]

None of the overseas conspiracies had significant impact on Indians inside India, and there were no major mutinies or violent outbursts. However, they did lead to profound fears of insurrection among British officials, preparing them to use extreme force to frighten the Indians into submission.[30]

Nationalist response to war

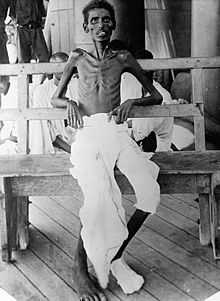

In the aftermath of the First World War, high casualty rates, soaring inflation compounded by heavy taxation, a widespread influenza epidemic and the disruption of trade during the war escalated human suffering in India.

The pre-war nationalist movement revived as moderate and extremist groups within the Congress submerged their differences in order to stand as a unified front. They argued their enormous services to the British Empire during the war demanded a reward, and demonstrated the Indian capacity for self-rule. In 1916, the Congress succeeded in forging the Lucknow Pact, a temporary alliance with the Muslim League over the issues of devolution of political power and the future of Islam in the region.

British reforms

The British themselves adopted a "carrot and stick" approach in recognition of India's support during the war and in response to renewed nationalist demands. In August 1917, Edwin Montagu, the secretary of state for India, made the historic announcement in Parliament that the British policy for India was "increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions with a view to the progressive realization of responsible government in India as an integral part of the British Empire." The means of achieving the proposed measure were later enshrined in the Government of India Act 1919, which introduced the principle of a dual mode of administration, or diarchy, in which both elected Indian legislators and appointed British officials shared power. The act also expanded the central and provincial legislatures and widened the franchise considerably. Diarchy set in motion certain real changes at the provincial level: a number of non-controversial or "transferred" portfolios, such as agriculture, local government, health, education, and public works, were handed over to Indians, while more sensitive matters such as finance, taxation, and maintaining law and order were retained by the provincial British administrators.[31]

Gandhi arrives in India

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (Mahatma Gandhi) had been a prominent leader of the Indian nationalist movement in South Africa, and had been a vocal opponent of basic discrimination and abusive labour treatment as well as suppressive police control such as the Rowlatt Acts. During these protests, Gandhi had perfected the concept of satyagraha, which had been inspired by the philosophy of Baba Ram Singh (famous for leading the Kuka Movement in the Punjab in 1872). In January 1914 (well before the First World War began) Gandhiji was successful. The hated legislation against Indians was repealed and all Indian political prisoners were released by General Jan Smuts.[32] Gandhi accomplished this through extensive use of non-violent protest, such as boycotting, protest marching, and fasting by him and his followers.[33]

Gandhi returned to India, on 9 January 1915 and initially entered the political fray not with calls for a nation-state, but in support of the unified commerce-oriented territory that the Congress Party had been asking for. Gandhi believed that the industrial development and educational development that the Europeans had brought with them were required to alleviate many of India's problems. Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a veteran Congressman and Indian leader, became Gandhi's mentor. Gandhi's ideas and strategies of non-violent civil disobedience initially appeared impractical to some Indians and Congressmen. In Gandhi's own words, "civil disobedience is civil breach of unmoral statutory enactments." It had to be carried out non-violently by withdrawing cooperation with the corrupt state. Gandhi's ability to inspire millions of common people became clear when he used satyagraha during the anti-Rowlatt Act protests in Punjab. Gandhi had great respect for Lokmanya Tilak. His programmes were all inspired by Tilak's "Chatusutri" programme.

Gandhi's vision would soon bring millions of regular Indians into the movement, transforming it from an elitist struggle to a national one. The nationalist cause was expanded to include the interests and industries that formed the economy of common Indians. For example, in Champaran, Bihar, Gandhi championed the plight of desperately poor sharecroppers and landless farmers who were being forced to pay oppressive taxes and grow cash crops at the expense of the subsistence crops which formed their food supply. The profits from the crops they grew were insufficient to provide for their sustenance.

The positive impact of reform was seriously undermined in 1919 by the Rowlatt Act, named after the recommendations made the previous year to the Imperial Legislative Council by the Rowlatt Commission. The Rowlatt Act vested the Viceroy's government with extraordinary powers to quell sedition by silencing the press, detaining the political activists without trial, and arresting any individuals suspected of sedition or treason without a warrant. In protest, a nationwide cessation of work (hartal) was called, marking the beginning of widespread, although not nationwide, popular discontent.

The agitation unleashed by the acts led to British attacks on demonstrators, culminating on 13 April 1919, in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre (also known as the Amritsar Massacre) in Amritsar, Punjab. The British military commander, Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer, blocked the main, and only entrance-cum-exit, and ordered his soldiers to fire into an unarmed and unsuspecting crowd of some 15,000 men, women and children. They had assembled peacefully at Jallianwala Bagh, a walled courtyard, but Dyer had wanted to execute the imposed ban on all meetings and proposed to teach all Indians a lesson the harsher way.[34] A total of 1,651 rounds were fired, killing 379 people (as according to an official British commission; Indian officials' estimates ranged as high as 1,499 and wounding 1,137 in the massacre.)[35] Dyer was forced to retire but was hailed as a hero in Britain, demonstrating to Indian nationalists that the Empire was beholden to public opinion in Britain, but not in India.[36] The episode dissolved wartime hopes of home rule and goodwill and opened a rift that could not be bridged short of complete independence.[37]

Non-cooperation movements

The independence movement as late as 1918 was an elitist movement far removed from the masses of India, focusing essentially on a unified commerce-oriented territory and hardly a call for a united nation. Gandhi changed all that and made it a mass movement.

First non-cooperation movement

At the Calcutta session of the Congress in September 1920, Gandhi convinced other leaders of the need to start a non-cooperation movement in support of Khilafat as well as for swaraj (self rule). The first satyagraha movement urged the use of khadi and Indian material as alternatives to those shipped from Britain. It also urged people to boycott British educational institutions and law courts; resign from government employment; refuse to pay taxes; and forsake British titles and honours. Although this came too late to influence the framing of the new Government of India Act 1919, the movement enjoyed widespread popular support, and the resulting unparalleled magnitude of disorder presented a serious challenge to foreign rule. However, Gandhi called off the movement following the Chauri Chaura incident, which saw the death of twenty-two policemen at the hands of an angry mob.

Membership in the party was opened to anyone prepared to pay a token fee, and a hierarchy of committees was established and made responsible for discipline and control over a hitherto amorphous and diffuse movement. The party was transformed from an elite organisation to one of mass national appeal and participation.

Gandhi was sentenced in 1922 to six years of prison, but was released after serving two. On his release from prison, he set up the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, on the banks of river Sabarmati, established the newspaper Young India, and inaugurated a series of reforms aimed at the socially disadvantaged within Hindu society — the rural poor, and the untouchables.[38][39]

This era saw the emergence of new generation of Indians from within the Congress Party, including C. Rajagopalachari, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Subhas Chandra Bose and others- who would later on come to form the prominent voices of the Indian independence movement, whether keeping with Gandhian Values, or, as in the case of Bose's Indian National Army, diverging from it.

The Indian political spectrum was further broadened in the mid-1920s by the emergence of both moderate and militant parties, such as the Swaraj Party, Hindu Mahasabha, Communist Party of India and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. Regional political organisations also continued to represent the interests of non-Brahmins in Madras, Mahars in Maharashtra, and Sikhs in Punjab. However, people like Mahakavi Subramanya Bharathi, Vanchinathan and Neelakanda Brahmachari played a major role from Tamil Nadu in both independence struggle and fighting for equality for all castes and communities.

Purna Swaraj

Following the rejection of the recommendations of the Simon Commission by Indians, an all-party conference was held at Bombay in May 1928. This was meant to instill a sense of resistance among people. The conference appointed a drafting committee under Motilal Nehru to draw up a constitution for India. The Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress asked the British government to accord dominion status to India by December 1929, or a countrywide civil disobedience movement would be launched. By 1929, however, in the midst of rising political discontent and increasingly violent regional movements, the call for complete independence from Britain began to find increasing grounds within the Congress leadership. Under the presidency of Jawaharlal Nehru at its historic Lahore session in December 1929, the Indian National Congress adopted a resolution calling for complete independence from the British. It authorised the Working Committee to launch a civil disobedience movement throughout the country. It was decided that 26 January 1930 should be observed all over India as the Purna Swaraj (total independence) Day. Many Indian political parties and Indian revolutionaries of a wide spectrum united to observe the day with honour and pride.

Karachi Congress session-1931

A special session was held in Karachi to endorse the Gandhi-Irwin Pact. The goal of Purna swaraj was reiterated. Two resolutions were adopted-one on Fundamental rights and other on National Economic program. This was the first time the congress spelt out what swaraj would mean for the masses.

Dandi March and Civil Disobedience

Gandhi emerged from his long seclusion by undertaking his most famous campaign, a march of about 400 kilometres (240 miles) from his commune in Ahmedabad to Dandi, on the coast of Gujarat between 11 March and 6 April 1930. The march is usually known as the Dandi March or the Salt Satyagraha. At Dandi, in protest against British taxes on salt, he and thousands of followers broke the law by making their own salt from seawater. It took 24 days for him to complete this march. Every day he covered 10 miles and gave many speeches.

In April 1930, there were violent police-crowd clashes in Calcutta. Approximately 100,000 people were imprisoned in the course of the Civil disobedience movement (1930–31), while in Peshawar unarmed demonstrators were fired upon in the Qissa Khwani bazaar massacre. The latter event catapulted the then newly formed Khudai Khidmatgar movement (founder Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the Frontier Gandhi) onto the National scene. While Gandhi was in jail, the first Round Table Conference was held in London in November 1930, without representation from the Indian National Congress. The ban upon the Congress was removed because of economic hardships caused by the satyagraha. Gandhi, along with other members of the Congress Working Committee, was released from prison in January 1931.

In March 1931, the Gandhi-Irwin Pact was signed, and the government agreed to set all political prisoners free (Although, some of the key revolutionaries were not set free and the death sentence for Bhagat Singh and his two comrades was not taken back which further intensified the agitation against Congress not only outside it but within the Congress itself). In return, Gandhi agreed to discontinue the civil disobedience movement and participate as the sole representative of the Congress in the second Round Table Conference, which was held in London in September 1931. However, the conference ended in failure in December 1931. Gandhi returned to India and decided to resume the civil disobedience movement in January 1932.

For the next few years, the Congress and the government were locked in conflict and negotiations until what became the Government of India Act 1935 could be hammered out. By then, the rift between the Congress and the Muslim League had become unbridgeable as each pointed the finger at the other acrimoniously. The Muslim League disputed the claim of the Congress to represent all people of India, while the Congress disputed the Muslim League's claim to voice the aspirations of all Muslims.

Elections and the Lahore resolution

The Government of India Act 1935, the voluminous and final constitutional effort at governing British India, articulated three major goals: establishing a loose federal structure, achieving provincial autonomy, and safeguarding minority interests through separate electorates. The federal provisions, intended to unite princely states and British India at the centre, were not implemented because of ambiguities in safeguarding the existing privileges of princes. In February 1937, however, provincial autonomy became a reality when elections were held; the Congress emerged as the dominant party with a clear majority in five provinces and held an upper hand in two, while the Muslim League performed poorly.

In 1939, the Viceroy Linlithgow declared India's entrance into the Second World War without consulting provincial governments. In protest, the Congress asked all of its elected representatives to resign from the government. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the president of the Muslim League, persuaded participants at the annual Muslim League session at Lahore in 1940 to adopt what later came to be known as the Lahore Resolution, demanding the division of India into two separate sovereign states, one Muslim, the other Hindu; sometimes referred to as Two Nation Theory. Although the idea of Pakistan had been introduced as early as 1930, very few had responded to it. However, the volatile political climate and hostilities between the Hindus and Muslims transformed the idea of Pakistan into a stronger demand.

Revolutionary activities

Apart from a few stray incidents, armed rebellions against the British rulers did not occur before the beginning of the 20th century. The Indian revolutionary underground began gathering momentum through the first decade of 20th century, with groups arising in Bengal, Maharastra, Odisha, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and the Madras Presidency including what is now called South India. More groups were scattered around India. Particularly notable movements arose in Bengal, especially around the Partition of Bengal in 1905, and in Punjab.[40] In the former case, it was the educated, intelligent and dedicated youth of the urban middle class Bhadralok community that came to form the "Classic" Indian revolutionary,[40] while the latter had an immense support base in the rural and Military society of the Punjab. Organisations like Jugantar and Anushilan Samiti had emerged in the 1900s (decade). The revolutionary philosophies and movement made their presence felt during the 1905 Partition of Bengal. Arguably, the initial steps to organize the revolutionaries were taken by Aurobindo Ghosh, his brother Barin Ghosh, Bhupendranath Datta etc. when they formed the Jugantar party in April 1906.[41] Jugantar was created as an inner circle of the Anushilan Samiti which was already present in Bengal mainly as a revolutionary society in the guise of a fitness club.

The Anushilan Samiti and Jugantar opened several branches throughout Bengal and other parts of India and recruited young men and women to participate in the revolutionary activities. Several murders and looting were done, with many revolutionaries being captured and imprisoned. The Jugantar party leaders like Barin Ghosh and Bagha Jatin initiated making of explosives. Amongst a number of notable events of political terrorism were the Alipore bomb case, the Muzaffarpur killing tried several activists and many were sentenced to deportation for life, while Khudiram Bose was hanged. The founding of the India House and The Indian Sociologist under Shyamji Krishna Varma in London in 1905 took the radical movement to Britain itself. On 1 July 1909, Madan Lal Dhingra, an Indian student closely identified with India House in London shot dead William Hutt Curzon Wylie, a British M.P. in London. 1912 saw the Delhi-Lahore Conspiracy planned under Rash Behari Bose, an erstwhile Jugantar member, to assassinate the then Viceroy of India Charles Hardinge. The conspiracy culminated in an attempt to Bomb the Viceregal procession on 23 December 1912, on the occasion of transferring the Imperial Capital from Calcutta to Delhi. In the aftermath of this event, concentrated police and intelligence efforts were made by the British Indian police to destroy the Bengali and Punjabi revolutionary underground, which came under intense pressure for sometime. Rash Behari successfully evaded capture for nearly three years. However, by the time that the First World War opened in Europe, the revolutionary movement in Bengal (and Punjab) had revived and was strong enough to nearly paralyse the local administration.[28][29] in 1914, Indian revolutionaries made conspiracies against British rule, but the plan failed and many revolutionaries sacrificed their life and others were arrested and sent to the Cellular Jail (Kalapani) in Andaman and Nicobar Islands. During the First World War, the revolutionaries planned to import arms and ammunitions from Germany and stage an armed revolution against the British.[42]

In 1905, during Dussehra festivities Vinayak Damodar Savarkar organised setting up of a bonfire of foreign goods and clothes. Along with his fellow students and friends he formed a political outfit called Abhinav Bharat. Vinayak was soon expelled from college due to his activities but was still permitted to take his Bachelor of Arts degree examinations.After his joining Gray's Inn law college in London Vinayak took accommodation at Bharat Bhawan India House. Organised by expatriate social and political activist Pandit Shyamji, India House was a thriving centre for student political activities. Savarkar soon founded the Free India Society to help organise fellow Indian students with the goal of fighting for complete independence through a revolution, declaring.Savarkar was studying revolutionary methods and he came into contact with a veteran of the Russian Revolution of 1905, who imparted him the knowledge of bomb-making. Savarkar had printed and circulated a manual amongst his friends, on bomb-making and other methods of guerrilla warfare. In 1909, Madan Lal Dhingra, a keen follower and friend of Savarkar, assassinated British MP Sir Curzon Wylie in a public meeting. Dhingra's action provoked controversy across Britain and India, evoking enthusiastic admiration as well as condemnation. Savarkar published an article in which he all but endorsed the murder and worked to organise support, both political and for Dhingra's legal defence. At a meeting of Indians called for a condemnation of Dhingra's deed, Savarkar protested the intention of condemnation and was drawn into a hot debate and angry scuffle with other attendants. A secretive and restricted trial and a sentence awarding the death penalty to Dhingra provoked an outcry and protest across the Indian student and political community. Strongly protesting the verdict, Savarkar struggled with British authorities in laying claim to Dhingra's remains following his execution. Savarkar hailed Dhingra as a hero and martyr, and began encouraging revolution with greater intensity. In London, Savarkar founded the Free India Society (FIS), and in December 1906 he opened a branch of Abhinav Bharat Society. This organisation drew a number of radical Indian students, including P.M. Bapat, V.V.S. Iyer, Madanlal Dhingra, and Virendranath Chattopadhyaya. Savarkar had lived in Paris for some time, and frequently visited the city after moving to London. When the then British Collector of Nasik, A.M.T. Jackson was shot by a youth, Veer Savarkar finally fell under the net of the British authorities. He was implicated in the murder citing his connections with India House. Savarkar was arrested in London on 13 March 1910 and sent to India. When the ship S.S. Morea reached the port of Marseilles on 8 July 1910, Savarkar escaped from his cell through a porthole and dived into the water, swimming to the shore in the hope that his friend would be there to receive him in a car. But his friend was late in arriving, and the alarm having been raised, Savarkar was re-arrested.Following a trial, Savarkar was sentenced to 50 years imprisonment and transported on 4 July 1911 to the infamous Cellular Jail in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. On 2 May 1921, the Savarkar brothers were moved to a jail in Ratnagiri, and later to the Yeravda Central Jail. He was finally released on 6 January 1924 under stringent restrictions – he was not to leave Ratnagiri District and was to refrain from political activities for the next five years. However, police restrictions on his activities would not be dropped until provincial autonomy was granted in 1937.

The Ghadar Party operated from abroad and cooperated with the revolutionaries in India. This party was instrumental in helping revolutionaries inside India catch hold of foreign arms. After the First World War, the revolutionary activities began to slowly wane as it suffered major setbacks due to the arrest of prominent leaders. In the 1920s, some revolutionary activists began to reorganise.

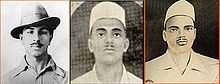

Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) was formed under the leadership of Chandrasekhar Azad. Kakori train robbery was done largely by the members of HSRA. Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt threw a bomb inside the Central Legislative Assembly on 8 April 1929 protesting against the passage of the Public Safety Bill and the Trade Disputes Bill while raising slogans of "Inquilab Zindabad", though no one was killed or injured in the bomb incident. Bhagat Singh surrendered after the bombing incident and a trial was conducted. Sukhdev and Rajguru were also arrested by police during search operations after the bombing incident. Following the trial (Central Assembly Bomb Case), Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were hanged in 1931. Allama Mashriqi founded Khaksar Tehreek in order to direct particularly the Muslims towards the independence movement.[43]

Surya Sen, along with other activists, raided the Chittagong armoury on 18 April 1930 to capture arms and ammunition and to destroy government communication system to establish a local governance. Pritilata Waddedar led an attack on a European club in Chittagong in 1932, while Bina Das attempted to assassinate Stanley Jackson, the Governor of Bengal inside the convocation hall of Calcutta University. Following the Chittagong armoury raid case, Surya Sen was hanged and several others were deported for life to the Cellular Jail in Andaman. The Bengal Volunteers started operating in 1928. On 8 December 1930, the Benoy-Badal-Dinesh trio of the party entered the secretariat Writers' Building in Kolkata and murdered Col. N. S. Simpson, the Inspector General of Prisons.

On 13 March 1940, Udham Singh shot Michael O'Dwyer(the last political murder out side India), generally held responsible for the Amritsar Massacre, in London. However, as the political scenario changed in the late 1930s — with the mainstream leaders considering several options offered by the British and with religious politics coming into play — revolutionary activities gradually declined. Many past revolutionaries joined mainstream politics by joining Congress and other parties, especially communist ones, while many of the activists were kept under hold in different jails across the country.

Government of India through the Ministry of Home Affairs has later notified 38 movements/struggles across Indian territories as the ones that led to the country gaining independence from the British Raj. The Kallara-Pangode Struggle is one of these 39 agitations.

Final process of Indian independence movement

In 1937, provincial elections were held and the Congress came to power in seven of the eleven provinces. This was a strong indicator of the Indian people's support for complete Independence.

When the Second World War started, Viceroy Linlithgow unilaterally declared India a belligerent on the side of Britain, without consulting the elected Indian representatives. In opposition to Linlithgow's action, the entire Congress leadership resigned from the local government councils. However, many wanted to support the British war effort, and indeed the British Indian Army is the largest volunteer force, numbering 2,500,000 men during the war.[44]

Especially during the Battle of Britain in 1940, Gandhi resisted calls for massive civil disobedience movements that came from within as well as outside his party, stating he did not seek India's independence out of the ashes of a destroyed Britain. In 1942, the Congress launched the Quit India movement. There was some violence but the Raj cracked down and arrested tens of thousands of Congress leaders, including all the main national and provincial figures. They were not released until the end of the war was in sight in 1945.

The independence movement saw the rise of three movements: The first of these, the Kakori conspiracy (9 August 1925) was led by Indian youth under the leadership of Pandit Ram Prasad Bismil; second was the Azad Hind movement led by Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose which saw its inception early in the war and joined Germany and Japan to fight Britain; the third one saw its inception in August 1942, was led by Lal Bahadur Shastri[45] and reflected the common man resulting the failure of the Cripps' mission to reach a consensus with the Indian political leadership over the transfer of power after the war.

Quit India Movement

The Quit India Movement (Bharat Chhodo Andolan) or the August Movement was a civil disobedience movement in India launched on 8 August 1942 in response to Gandhi's call for immediate independence of India and against sending Indians to World War II. He asked all teachers to leave their schools, and other Indians to leave their respective jobs and take part in this movement. Due to Gandhi's political influence, his request was followed by a massive proportion of the population.

At the outbreak of war, the Congress Party had during the Wardha meeting of the working-committee in September 1939, passed a resolution conditionally supporting the fight against fascism,[46] but were rebuffed when they asked for independence in return. In March 1942, faced with an increasingly dissatisfied sub-continent only reluctantly participating in the war, and deteriorations in the war situation in Europe and South East Asia, and with growing dissatisfactions among Indian troops- especially in Europe- and among the civilian population in the sub-continent, the British government sent a delegation to India under Stafford Cripps, in what came to be known as the Cripps' Mission. The purpose of the mission was to negotiate with the Indian National Congress a deal to obtain total co-operation during the war, in return of progressive devolution and distribution of power from the crown and the Viceroy to elected Indian legislature. However, the talks failed, having failed to address the key demand of a timeframe towards self-government, and of definition of the powers to be relinquished, essentially portraying an offer of limited dominion-status that was wholly unacceptable to the Indian movement.[47] To force the British Raj to meet its demands and to obtain definitive word on total independence, the Congress took the decision to launch the Quit India Movement.

The aim of the movement was to force the British Government to the negotiating table by holding the Allied war effort hostage. The call for determined but passive resistance that signified the certitude that Gandhi foresaw for the movement is best described by his call to Do or Die, issued on 8 August at the Gowalia Tank Maidan in Bombay, since renamed August Kranti Maidan (August Revolution Ground). However, almost the entire Congress leadership, and not merely at the national level, was put into confinement less than 24 hours after Gandhi's speech, and the greater number of the Congress khiland were to spend the rest of the war in jail.

On 8 August 1942, the Quit India resolution was passed at the Bombay session of the All India Congress Committee (AICC). The draft proposed that if the British did not accede to the demands, a massive Civil Disobedience would be launched. However, it was an extremely controversial decision. At Gowalia Tank, Mumbai, Gandhi urged Indians to follow a non-violent civil disobedience. Gandhi told the masses to act as an independent nation and not to follow the orders of the British. The British, already alarmed by the advance of the Japanese army to the India–Burma border, responded the next day by imprisoning Gandhi at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. The Congress Party's Working Committee, or national leadership was arrested all together and imprisoned at the Ahmednagar Fort. They also banned the party altogether. All the major leaders of the INC were arrested and detained. As the masses were leaderless the protest took a violent turn. Large-scale protests and demonstrations were held all over the country. Workers remained absent en masse and strikes were called. The movement also saw widespread acts of sabotage, Indian under-ground organisation carried out bomb attacks on allied supply convoys, government buildings were set on fire, electricity lines were disconnected and transport and communication lines were severed. The disruptions were under control in a few weeks and had little impact on the war effort. The movement soon became a leaderless act of defiance, with a number of acts that deviated from Gandhi's principle of non-violence. In large parts of the country, the local underground organisations took over the movement. However, by 1943, Quit India had petered out.

All the other major parties rejected the Quit India plan, and most cooperated closely with the British, as did the princely states, the civil service and the police. The Muslim League supported the Raj and grew rapidly in membership, and in influence with the British.

Indian National Army

The entry of India into the war was strongly opposed by Subhas Chandra Bose, who had been elected President of the Congress in 1938 and 1939, but later removed from the presidency and expelled from the organization. Bose then founded the All India Forward Bloc. In 1940, a year after war broke out, the British had put Bose under house arrest in Calcutta. However, he escaped and made his way through Afghanistan to Nazi Germany to seek Hitler and Mussolini's help for raising an army to fight the British. The Free India Legion comprising Erwin Rommel's Indian POWs was formed. However, in light of Germany's changing fortunes, a German land invasion of India became untenable and Hitler advised Bose to go to Japan and arranged for a submarine. Bose was ferried to Japanese Southeast Asia, where he formed the Azad Hind Government, a Provisional Free Indian Government in exile, and reorganised the Indian National Army composed of Indian POWs and volunteering Indian expatriates in South-East Asia, with the help of the Japanese. Its aim was to reach India as a fighting force that would build on public resentment to inspire revolts among Indian soldiers to defeat the British raj.

The INA was to see action against the allies, including the British Indian Army, in the forests of Arakan, Burma and in Assam, laying siege on Imphal and Kohima with the Japanese 15th Army. During the war, the Andaman and Nicobar islands were captured by the Japanese and handed over by them to the INA.

The INA failed owing to disrupted logistics, poor supplies from the Japanese, and lack of training.[48] It surrendered unconditionally to the British in Singapore in 1945. Bose, however, attempted to escape to Japanese-held Manchuria in an attempt to escape to the Soviet Union, marking the end of the entire Azad Hindmovement

Christmas Island Mutiny and Royal Indian Navy mutiny

After two Japanese attacks on Christmas Island in late February and early March 1942, relations between the British officers and their Indian troops broke down. On the night of 10 March, the Indian troops assisted by Sikh policemen mutinied, killing five British soldiers and imprisoning the remaining 21 Europeans on the island. Later on 31 March, a Japanese fleet arrived at the island and the Indians surrendered.[49]

The Royal Indian Navy mutiny (also called the Bombay Mutiny) encompasses a total strike and subsequent mutiny by Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy on board ship and shore establishments at Bombay (Mumbai) harbour on 18 February 1946. From the initial flashpoint in Bombay, the mutiny spread and found support throughout British India, from Karachi to Calcutta and ultimately came to involve 78 ships, 20 shore establishments and 20,000 sailors.[50]

The agitations, mass strikes, demonstrations and consequently support for the mutineers, therefore continued several days even after the mutiny had been called off. Along with this, the assessment may be made that it described in crystal clear terms to the government that the British Indian Armed forces could no longer be universally relied upon for support in crisis, and even more it was more likely itself to be the source of the sparks that would ignite trouble in a country fast slipping out of the scenario of political settlement.[51]

Independence and partition of India

On 3 June 1947, Viscount Louis Mountbatten, the last British Governor-General of India, announced the partitioning of British India into India and Pakistan. With the speedy passage through the British Parliament of the Indian Independence Act 1947, at 11:57 on 14 August 1947 Pakistan was declared a separate nation, and at 12:02, just after midnight, on 15 August 1947, India also became an independent nation. Violent clashes between Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims followed. Prime Minister Nehru and deputy prime minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel invited Mountbatten to continue as Governor General of India. He was replaced in June 1948 by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari. Patel took on the responsibility of bringing into the Indian Union 565 princely states, steering efforts by his "iron fist in a velvet glove" policies, exemplified by the use of military force to integrate Junagadh and Hyderabad State into India (Operation Polo). On the other hand, Pandit Jawahar Lal Nehru kept the issue of Kashmir in his hands.

The Constituent Assembly completed the work of drafting the constitution on 26 November 1949; on 26 January 1950, the Republic of India was officially proclaimed. The Constituent Assembly elected Dr. Rajendra Prasad as the first President of India, taking over from Governor General Rajgopalachari. Subsequently India invaded and annexed Goa and Portugal's other Indian enclaves in 1961), the French ceded Chandernagore in 1951, and Pondichéry and its remaining Indian colonies in 1956, and Sikkim voted to join the Indian Union in 1975.

Following independence in 1947, India remained in the Commonwealth of Nations, and relations between the UK and India have been friendly. There are many areas in which the two countries seek stronger ties for mutual benefit, and there are also strong cultural and social ties between the two nations. The UK has an ethnic Indian population of over 1.6 million. In 2010, Prime Minister David Cameron described Indian – British relations as a "New Special Relationship".[52]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chandra 1989, p. 26

- ↑ Chandra 1989, p. 521

- ↑ Heehs 1998, p. 9

- ↑ The English colonial empire, including the territories and trading posts in Asia, came under British control following the union of England and Scotland in 1707.

- ↑ Heehs 1998, pp. 9–10

- ↑ Heehs 1998, pp. 11–12

- ↑ Rout, Hemant Kumar (2012). "Villages fight over martyr’s death place - The New Indian Express". newindianexpress.com. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

historians claim he is actually the first martyr in the country’s freedom movement because none was killed by the Britishers before 1806

- ↑ "Controversy over Jayee Rajguru’s place of assassination | Odisha Reporter". odishareporter.in. 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

was assassinated by the British government in a brutal manner on December 6, 1806

- ↑ Mohanty, N.R. (August 2008). "The Oriya Paika Rebellion of 1817" (PDF). Orissa Review: 1–3. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Paikaray, Braja (February–March 2008). "Khurda Paik Rebellion - The First Independence War of India" (PDF). Orissa Review: 45–50. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Paik Rebellion". Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Chandra 1989, p. 33

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chandra 1989, p. 34

- ↑ "The Uprising of 1857". Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 November 2009.

- ↑ Chandra 1989, p. 31

- ↑ David, S (202) The Indian Mutiny, Penguin; p. 122

- ↑ Chandra 1989, p. 35

- ↑ Chandra 1989, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Chandra 1989, p. 39

- ↑ Heehs 1998, p. 32

- ↑ "Official, India". World Digital Library. 1890–1923. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ↑ Heehs 1998, pp. 47–48

- ↑ Heehs 1998, p. 48

- ↑ Robert P. O'Kell (2014). Disraeli: The Romance of Politics. U of Toronto Press. pp. 443–44.

- ↑ John R. McLane, "The Decision to Partition Bengal in 1905," Indian Economic and Social History Review, July 1965, 2#3, pp 221–237

- ↑ Jalal, Ayesha (1994) The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4

- ↑ Official website, Government of Pakistan. "The Statesman: Jinnah's differences with the Congress". Archived from the original on 27 January 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2006.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Gupta 1997, p. 12

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Popplewell 1995, p. 201

- ↑ Lawrence James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (2000) pp 439–518

- ↑ James, Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (2000) pp 459–60, 519–20

- ↑ Denis Judd, Empire: The British Imperial Experience From 1765 To The Present (pp 226-411998)

- ↑ "The Indian Independence Movement". Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ↑ Nigel Collett, The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer (2006)

- ↑ Nick Lloyd, The Amritsar Massacre: The Untold Story of One Fateful Day (2011)

- ↑ Derek Sayer, "British Reaction to the Amritsar Massacre 1919–1920," Past & Present, May 1991, Issue 131, pp 130–164

- ↑ Dennis Judd, "The Amritsar Massacre of 1919: Gandhi, the Raj and the Growth of Indian Nationalism, 1915–39," in Judd, Empire: The British Imperial Experience from 1765 to the Present (1996) pp 258- 72

- ↑ Sankar Ghose, Mahatma Gandhi (1991) p. 107

- ↑ Sanjay Paswan and Pramanshi Jaideva, Encyclopaedia of Dalits in India (2003) p. 43

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Fraser 1977, p. 257

- ↑ Banglapedia article by Mohammad Shah

- ↑ Rowlatt Report (§109–110); First Spark of Revolution by A.C. Guha, pp. 424–34.

- ↑ Khaksar Tehrik Ki Jiddo Juhad Volume 1. Author Khaksar Sher Zaman

- ↑ Roy, Kaushik, "Military Loyalty in the Colonial Context: A Case Study of the Indian Army during World War II," Journal of Military History (2009) 73#2 pp 144–172

- ↑ Dr.'Krant'M.L.Verma Swadhinta Sangram Ke Krantikari Sahitya Ka Itihas (Vol-2) p.559

- ↑ "The Congress and The Freedom Movement". Indian National Congress. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 24 September 2007.

- ↑ Culture and Combat in the Colonies. The Indian Army in the Second World War. Tarak Barkawi. J Contemp History. 41(2), 325–355.pp:332

- ↑ "Forgotten armies of the East – Le Monde diplomatique – English edition". Mondediplo.com. 10 May 2005. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- ↑ "Christmas Island History". Christmas Island Tourism Association. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ↑ Notes on India By Robert Bohm.pp213

- ↑ James L. Raj; Making and unmaking of British India. Abacus. 1997. p571, p598 and; Unpublished, Public Relations Office, London. War Office. 208/819A 25C

- ↑ Nelson, Dean (7 July 2010). "Ministers to build a new 'special relationship' with India". The Daily Telegraph.

Bibliography

- Brown, Judith M. Gandhi's Rise to Power: Indian Politics 1915–1922 (Cambridge South Asian Studies) (1974)

- MK Gandhi. My Experiments with Truth Editor's note by Mahadev Desai (Beacon Press) (1993)

- Brown, Judith M., 'Gandhi and Civil Resistance in India, 1917–47', in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garton Ash (eds.), Civil Resistance and Power Politics: The Experience of Non-violent Action from Gandhi to the Present. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-955201-6.

- Jalal, Ayesha. The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan (Cambridge South Asian Studies) (1994)

- Majumdar, R.C. History of the Freedom movement in India. ISBN 0-8364-2376-3.

- Gandhi, Mohandas (1993). An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments With Truth. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5909-9.

- Sofri, Gianni (1995–1999). Gandhi and India: A Century in Focus. Janet Sethre Paxia (translator) (English edition translated from the Italian ed.). Gloucestershire: The Windrush Press. ISBN 1-900624-12-5.

- Gonsalves, Peter. Khadi: Gandhi's Mega Symbol of Subversion, (Sage Publications), (2012)

- Gopal, Sarvepalli. Jawaharlal Nehru – Volume One: 1889 – 1947 – A Biography (1975), standard scholarly biography

- Seal, Anil (1968). Emergence of Indian Nationalism: Competition and Collaboration in the Later Nineteenth Century. London: Cambridge U.P. ISBN 0-521-06274-8.

- Singh, Jaswant. Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence (2010)

- Chandra, Bipan; Mridula Mukherjee, Aditya Mukherjee, Sucheta Mahajan, K.N. Panikkar (1989). India's Struggle for Independence. New Delhi: Penguin Books. p. 600. ISBN 978-0-14-010781-4.

- Heehs, Peter (1998). India's Freedom Struggle: A Short History. Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-19-562798-5.

- Sarkar, Sumit (1983). Modern India: 1885–1947. Madras: Macmillan. p. 486. ISBN 0-333-90425-7.

- Wolpert, Stanley A. Jinnah of Pakistan (2005)

- Wolpert, Stanley A. Gandhi's Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi (2002)

- M.L.Verma Swadhinta Sangram Ke Krantikari Sahitya Ka Itihas (3 Volumes) 2006 New Delhi Praveen Prakashan ISBN 81-7783-122-4.

- Sharma Vidyarnav Yug Ke Devta : Bismil Aur Ashfaq 2004 Delhi Praveen Prakashan ISBN 81-7783-078-3.

- M.L.Verma Sarfaroshi Ki Tamanna (4 Volumes) 1997 Delhi Praveen Prakashan.

- Mahaur Bhagwandas Kakori Shaheed Smriti 1977 Lucknow Kakori Shaheed Ardhshatabdi Samaroh Samiti.

- South Asian History And Culture Vol.-2 pp. 16–36,Taylor And Francis group

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indian independence movement. |

- Muslim freedom martyrs of India – TCN News

- Indian Government

- Timeline of Indian independence movement

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||