Imperial Abbey of Kempten

| Princely Abbey of Kempten | |||||

| Fürststift Kempten | |||||

| State of the Holy Roman Empire | |||||

| |||||

|

| |||||

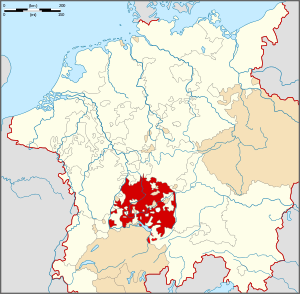

Imperial City and Imperial Abbey of Kempten, c. 1800 | |||||

| Capital | Kempten | ||||

| Government | Imperial abbey | ||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| - | Abbey founded | 752 | |||

| - | Imperial immediacy confirmed | 1062 | |||

| - | Prince–Abbacy | 1213 | |||

| - | Joined Swabian Circle | 1500 | |||

| - | Joined Catholic League | 1609 | |||

| - | Abbey property purchased by the City of Kempten | 1525 | |||

| - | Mediatised to Bavaria | 1803 | |||

| - | Cities united | 1819 | |||

| Coordinates: 47°43′40″N 10°18′48″E / 47.7277°N 10.3132°E | |||||

The Imperial Abbey of Kempten or Princely Abbey of Kempten[1] (German: Fürststift Kempten or Fürstabtei Kempten) was an ecclesiastical state of the Holy Roman Empire for centuries until it was annexed to the Electorate of Bavaria in the course of the German mediatization in 1803.

Geography

Located within the former Duchy of Swabia, the Princely Abbey was the second largest ecclesiastical Imperial State of the Swabian Circle by area, after the Prince-Bishopric of Augsburg. It stretched along the Iller River in the Allgäu region, from Waltenhofen (Martinszell) in the south to Legau and Grönenbach in the northwest, and up to Ronsberg and Unterthingau in the east.

The Imperial city of Kempten itself formed an Imperial State in its own right and an enclave within the abbey's territory. The Princely Abbey of Kempten covered approximately 1,000 square kilometres (390 square miles) and included some 85 villages and hundreds of hamlets and farms, making it one of the largest Imperial abbeys. At the time of its annexation to Bavaria in 1802, it had some 42,000 subjects.[2]

History

According to the 11th-century chronicles by Hermann of Reichenau, the monastery of Kempten dedicated to Virgin Mary and Gordianus and Epimachus was established around 752 under its first abbot Audogar. According to other sources, it was however erected by two Benedictine monks from the Abbey of Saint Gall, Magnus of Füssen and Theodor, who also founded the St Mang's Monastery in Füssen.[3]

The abbey had financial and political support from the ruling Carolingian dynasty, mainly from Hildegard of Vinzgouw, the second wife of Charlemagne, and her son Louis the Pious. It soon became one of the more prominent monasteries in the Carolingian Empire. It was rebuilt in 941 by the abbot Ulrich of Augsburg after Magyar raids.

Imperial Status

The status of Imperial immediacy (Reichsfreiheit) was confirmed by King Henry IV of Germany in 1062. The Kempten abbots assumed the title of a Prince-abbot (Fürstabt) in the 12th century. In 1213 the Hohenstaufen king Frederick II of Germany vested them with comital privileges in the abbey's territory and in 1218 also ceded the rights of a secular Vogt protector, confirmed by his son King Henry VII in 1224.

Several attempts under their successors Conrad IV and Rudolph I to regain the secular lordship ultimatively failed. The abbey's development of an Imperial estate was accomplished with the bestowing of a single vote in the Imperial Diet in 1548.

By a privilege granted by King Rudolph I, the town of Kempten had freed itself from the authority of the abbot and became a Free imperial city, starting a long rivalry. When during the German Peasants' War in 1525 the Kempten Prince-abbot had to seek shelter within the city walls, he was forced to sell his last property rights in the Imperial City in the so-called “Great Purchase”, marking the start of a tense co-existence of two independent estates bearing the same name next to each other.

Thirty Years' War

More conflict arose after the Imperial city of Kempten from 1527 onwards converted to Protestantism in direct opposition to the Catholic monastery. The citizens signed the 1529 Protestation at Speyer and the 1530 Augsburg Confession. In turn, Kempten Abbey joined the Catholic League in 1609. During the Thirty Years' War, the monastery buildings were burnt to the ground by Swedish troops in 1632.

From 1651, the Kempten Prince-abbot Roman Giel of Gielsberg commissioned a princely residence and the new abbey church St. Lorenz Basilica, one of the first major churches to be built after the war in Germany. Still in 1706, Kempten was the center of a religious controversy, when the abbot confiscated a Reformed church, which provoked King Frederick I of Prussia to confiscate all Benedictine properties until the church was returned.[4]

Secularisation

Emperor Charles VI granted the monastery complex town privileges in 1728, however, an autonomous municipality was not established. In 1775 the abbey ordered the last witchcraft trial in the Holy Roman Empire,[5] when Anna Maria Schwegelin was sentenced to death by decapitation, though the verdict was not enforced.

During the Napoleonic Wars the abbey's territory was occupied by Bavarian troops in 1802 and was formerly dissolved in the subsequent German mediatization (Reichsdeputationshauptschluss). The abbey's territory as well as the Imperial city of Kempten were annexed by Bavaria, in 1819 both territories were merged into a single communal entity within the Kingdom of Bavaria.

Notes

- ↑ There was a difference between a Reichsabtei (Imperial Abbey) and a Fürstabtei (Princely Abbey), particularly as regard the status of the abbot but, unfortunately, the tendency in English has been to lump them under the term "Imperial Abbey".

- ↑ http://www.historisches-lexikon-bayerns.de/artikel/artikel_45400

- ↑ Saint Gall (Princely Abbey) in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ↑ Whaley 2011, p. 324

- ↑ Beales 2003, p. 62

Bibliography

- Beales, Derek Edward Dawson (2003). Prosperity and Plunder: European Catholic Monasteries in the Age of Revolution, 1650-1815 (2003 ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521590907. - Total pages: 395

- Whaley, Joachim (2011). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume II: The Peace of Westphalia to the Dissolution of the Reich, 1648-1806 Oxford History of Early Modern Europe Series (2011 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199693078. - Total pages: 752

| ||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)