Immigration Act of 1924

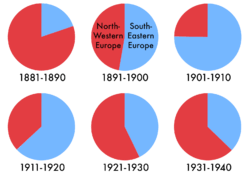

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the National Origins Act, and Asian Exclusion Act (Pub.L. 68–139, 43 Stat. 153, enacted May 26, 1924), was a United States federal law that limited the annual number of immigrants who could be admitted from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were already living in the United States in 1890, down from the 3% cap set by the Immigration Restriction Act of 1921, according to the Census of 1890. It superseded the 1921 Emergency Quota Act. The law was primarily aimed at further restricting immigration of Southern Europeans and Eastern Europeans. In addition, it severely restricted the immigration of Africans and prohibited the immigration of Arabs, East Asians, and Indians. According to the U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian the purpose of the act was "to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity".[1] Congressional opposition was minimal.

Provisions

The Immigration Act made permanent the basic limitations on immigration into the United States established in 1921 and modified the National Origins Formula established then. In conjunction with the Immigration Act of 1917, it governed American immigration policy until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which revised it completely.

For the next three years, until June 30, 1927, the 1924 Act set the annual quota of any nationality at 2% of the number of foreign-born persons of such nationality resident in the United States in 1890. That revised formula reduced total immigration from 357,803 in 1923–24 to 164,667 in 1924–25. The law's impact varied widely by country. Immigration from Great Britain and Ireland fell 19%, while immigration from Italy fell more than 90%.[2]

The Act established preferences under the quota system for certain relatives of U.S. residents, including their unmarried children under 21, their parents, and spouses aged 21 and over. It also preferred immigrants aged 21 and over who were skilled in agriculture, as well as their wives and dependent children under age 16. Non-quota status was accorded to: wives and unmarried children under 18 of U.S. citizens; natives of Western Hemisphere countries, with their families; non-immigrants; and certain others. Subsequent amendments eliminated certain elements of this law's inherent discrimination against women.

The 1924 Act also established the "consular control system" of immigration, which divided responsibility for immigration between the State Department and the Immigration and Naturalization Service. It mandated that no alien should be allowed to enter the United States without a valid immigration visa issued by an American consular officer abroad.

It provided that no alien ineligible to become a citizen could be admitted to the United States as an immigrant. This was aimed primarily at Japanese and Chinese aliens. It imposed fines on transportation companies who landed aliens in violation of U.S. immigration laws. It defined the term "immigrant" and designated all other alien entries into the United States as "non-immigrant", that is, temporary visitors. It established classes of admission for such non-immigrants.

History

Restriction of Southern and Eastern European immigration was first proposed in 1909 by Senator Henry Cabot Lodge.[3]

In the wake of the Post-World War I recession, many Americans believed that bringing in more immigrants from other nations would only make the unemployment rate higher. The Red Scare of 1919–1921 had fueled xenophobic fears of foreign radicals migrating to undermine American values and provoke an uprising like Russia's 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.[4] The number of immigrants entering the United States decreased for about a year from July 1919 to June 1920 but also doubled the year after that (Cannato 331).[5]

Congressman Albert Johnson and Senator David Reed were the two main architects of the act. In the wake of intense lobbying, the Act passed with strong congressional support.[6] There were nine dissenting votes in the Senate[7] and a handful of opponents in the House, the most vigorous of whom was freshman Brooklyn Representative Emanuel Celler. Over the succeeding four decades, Celler made the repeal of the Act his personal crusade.

Proponents of the Act sought to establish a distinct American identity by favoring native-born Americans over Jews, Southern Europeans, and Eastern Europeans in order to "maintain the racial preponderance of the basic strain on our people and thereby to stabilize the ethnic composition of the population".[8][9] Reed told the Senate that earlier legislation "disregards entirely those of us who are interested in keeping American stock up to the highest standard – that is, the people who were born here".[10] Southern/Eastern Europeans and Jews, he believed, arrived sick and starving and therefore less capable of contributing to the American economy, and unable to adapt to American culture.[8]

Some of the law's strongest supporters were influenced by Madison Grant and his 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race. Grant was a eugenicist and an advocate of the racial hygiene theory. His data purported to show the superiority of the founding Nordic races. Most proponents of the law were rather concerned with upholding an ethnic status quo and avoiding competition with foreign workers.[11] Samuel Gompers, a Jewish immigrant and founder of the AFL, supported the Act because he opposed the cheap labor that immigration represented, despite the fact that the Act would sharply reduce Jewish immigration.[12]

The law sharply curtailed immigration from those countries that were previously host to the vast majority of the Jews in America, almost 75% of whom immigrated from Russia alone.[13] Because Eastern European immigration only became substantial in the final decades of the 19th century, the law's use of the population of the United States in 1890 as the basis for calculating quotas effectively made mass migration from Eastern Europe, where the vast majority of the Jewish diaspora lived at the time, impossible.[14]

Lobbyists from California, where a majority of Japanese and other East Asian immigrants had settled, were especially concerned with excluding Asian immigrants. An 1882 law had already put an end to Chinese immigration, but as Japanese (and, to a lesser degree, Korean and Filipino) laborers began arriving and putting down roots in Western states, an exclusionary movement formed in reaction to the "Yellow Peril." Valentine S. McClatchy, founder of The McClatchy Company and a leader of the anti-Japanese movement, argued, "They come here specifically and professedly for the purpose of colonizing and establishing here permanently the proud Yamato race," citing their supposed inability to assimilate to American culture and the economic threat they posed to white businessmen and farmers. Despite some hesitation from President Calvin Coolidge and strong opposition from the Japanese government, with which the U.S. government had previously maintained a cordial economic and political relationship, the act was signed into law on May 24, 1924.[4]

Results

The Act controlled "undesirable" immigration by establishing quotas. The Act barred specific origins from the Asia–Pacific Triangle, which included Japan, China, the Philippines (then under U.S. control), Siam (Thailand), French Indochina (Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia), Singapore (then a British colony), Korea, the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia), Burma (Myanmar), India, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and Malaya (mainland part of Malaysia).[15] Based on the Naturalization Acts of 1790 and 1870, only people of white or African descent were eligible for naturalization, and the Act forbade further immigration of any persons ineligible to be naturalized.[15] The Act set no limits on immigration from Latin American countries.[16]

In the 10 years following 1900, about 200,000 Italians immigrated annually. With the imposition of the 1924 quota, 4,000 per year were allowed. By contrast, the annual quota for Germany after the passage of the Act was over 57,000. Some 86% of the 155,000 permitted to enter under the Act were from Northern European countries, with Germany (including Poles; see: Partitions of Poland), Britain, and Ireland having the highest quotas. The new quotas for immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe were so restrictive that in 1924 there were more Italians, Czechs, Yugoslavs, Greeks, Lithuanians, Hungarians, Portuguese, Romanians, Spaniards, Jews, Chinese, and Japanese that left the United States than those who arrived as immigrants.[17]

The quotas remained in place with minor alterations until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965.

See also

- Anti-Italianism

- Eugenics in the United States

- History of laws concerning immigration and naturalization in the United States

- Leslie Charteris, specifically exempted from the provisions of the Act

- List of United States Immigration Acts

- Racial equality proposal

- White Australia policy

- Antisemitism in the United States

- Yellow Peril

References

- ↑ "The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act)". U.S Department of State Office of the Historian. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ↑ Murray, Robert K. (1976). The 103rd Ballot: Democrats and the Disaster in Madison Square Garden. New York: Harper & Row. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-06-013124-1.

- ↑ Lodge, Henry (1909). "The Restriction of Immigration" (PDF). University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 2012-03-02.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Imai, Shiho. "Immigration Act of 1924". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ Cannato, Vincent J. American Passage: The History of Ellis Island. New York: Harper, 2009. Print.

- ↑ "Immigration Bill Passes Senate by Vote of 62 to 6". New York Times. April 19, 1924. Retrieved February 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Senate Vote #126 (May 15, 1924)". govtrack.us. Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jones, Maldwyn Allen (1960). American Immigration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 277.

- ↑ "Who Was Shut Out?: Immigration Quotas, 1925–1927". History Matters. George Mason University. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ↑ Stephenson, George M. (1964). A History of American Immigration. 1820–1924. New York: Russel & Russel. p. 190.

- ↑ Eckerson, Helen F. (1966). "Immigration and National Origins". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. The New Immigration 367: 4–14. doi:10.1177/000271626636700102. JSTOR 1034838.

- ↑ Gompers, Samuel. "Immigration and labor".

- ↑ Stuart J. Wright, An Emotional Gauntlet: From Life in Peacetime America to the War in European Skies (University of Wisconsin Press, 2004), 163

- ↑ Julian Levinson, Exiles on Main Street: Jewish American Writers and American Literary Culture (Indiana University Press, 2008), 54

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Guisepi, Robert A. (January 29, 2007). "Asian Americans". World History International.

- ↑ Hayes, Helene (2001). U.S. Immigration Policy and the Undocumented. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. p. . ISBN 978-0-275-95411-6.

- ↑ Steven G. Koven, Frank Götzke, American Immigration Policy: Confronting the Nation's Challenges (Springer, 2010), 133

Sources

- Lemay, Michael Robert; Barkan, Elliott Robert, eds. (1999). U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Issues: A Documentary History. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30156-8.

- Zolberg, Aristide (2006). A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02218-8.

External links

- Statistics of who was allowed in after the Immigration Act of 1924

- "'Shut the Door': A Senator Speaks for Immigration Restriction" – transcript of speech given before Congress by Sen. Ellison D. Smith, April 9, 1924

- Eugenics Laws Restricting Immigration

- Text of 1924 Immigration Act and enabling proclamation by the President

- Quotas defined in Immigration Law of 1924

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||