Imbros

|

Mountains of Imbros | |

Gökçeada/Imbros | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Aegean Sea |

| Coordinates | 40°09′39″N 25°50′40″E / 40.16083°N 25.84444°ECoordinates: 40°09′39″N 25°50′40″E / 40.16083°N 25.84444°E |

| Area | 279 km2 (108 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 673 m (2,208 ft) |

| Highest point | İlyas Dağ |

| Country | |

|

Turkey | |

| District | Gökçeada District |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 8,210 (as of 2011) |

Imbros or İmroz, officially changed to Gökçeada since July 29, 1970[1][2] (older name in Turkish: İmroz; Greek: Ίμβρος Imvros), is the largest island of Turkey and the seat of Gökçeada District of Çanakkale Province. It is located in the Aegean Sea, at the entrance of Saros Bay and is also the westernmost point of Turkey (Cape İncirburnu). Imbros has an area of 279 km2 (108 sq mi) and contains some wooded areas.[3]

According to the 2011 census, the island-district of Gökçeada has a population of 8,210.[4] The main industries of Imbros are fishing and tourism. The population is predominantly Turkish but there are still about 250 Greeks on Imbros, most of them elderly. The island was primarily inhabited by ethnic Greeks[1] from ancient times through to approximately the middle of the twentieth century, when many emigrated to Greece, western Europe, the United States and Australia, due to a campaign of state-sponsored discrimination.[1][5][6] The island is noted for its vineyards and wine production.

History

In mythology

According to Greek mythology, the palace of Thetis, mother of Achilles, king of Phthia, was situated between Imbros and Samothrace. The stables of the winged horses of Poseidon were said to lie between Imbros and Tenedos.

Homer, in The Iliad wrote:

- In the depths of the sea on the cliff

- Between Tenedos and craggy Imbros

- There is a cave, wide gaping

- Poseidon who made the earth tremble,

- stopped the horses there.[7]

Eëtion, a lord of or ruler over the island of Imbros is also mentioned in the Iliad. He buys Priam's captured son Lycaon and restores him to his father.[8]

In antiquity

For ancient Greeks, the islands of Lemnos and Imbros were sacred to Hephaestus, god of metallurgy, and on ancient coins of Imbros an ithyphallic Hephaestus appears. In classical antiquity, Imbros, like Lemnos, was an Athenian cleruchy, a colony whose settlers retained Athenian citizenship; although since the Imbrians appear on the Athenian tribute lists, there may have been a division with the native population. The original inhabitants of Imbros were Pelasgians, as mentioned by Herodotus in The Histories.[9] Miltiades conquered the island from Persia after the battle of Salamis; the colony was established about 450 BC, during the first Athenian empire, and was retained by Athens (with brief exceptions) for the next six centuries. Thucydides, in his History of the Peloponnesian War describes the colonization of Imbros,[10] and at several places in his narrative mentions the contribution of Imbrians in support of Athens during various military actions.[11] He also recounts the escape of an Athenian squadron to Imbros.[12] In the late 2nd century A.D., the island may have become independent under Septimius Severus.[13]

Byzantine era

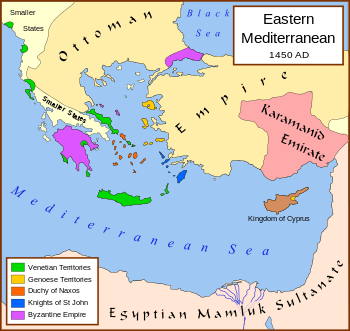

Prior to the Fall of Constantinople, several larger islands south of Imbros were under Genoese rule, part of territory historically held in the eastern Mediterranean by the independent Maritime Republic of Genoa (1005-1797, predating the East–West schism of 1054) a political development within the Western Roman Empire of city-states such as Venice, Pisa and Amalfi. Defended by the Genoese Navy, one of the largest and most powerful in the Mediterranean, Corsica remained a prominent western Mediterranean territory in the Tyrhennian Sea until Napoleon's conquest.

At the beginning of the 13th century, when the Fourth Crusade and its aftermath temporarily disrupted Venice's relations with the Byzantine Empire, Genoa expanded its influence north of Imbros, into the Black Sea and Crimea. An extensive network of mercantile routes and associated ports promoted expansion of Byzantine culture, its goods and services - including scholars and craftsmen schooled in ancient Classical traditions - into Italy, France, Greece, Monaco, Russia, Tunisia, Turkey and Ukraine. The Renaissance's renewal of European culture was spawned in part by the rapid influx of exiles from Constantinople at the close of the 15th century. Not all the trade exchanges were as beneficial however: in the debit column can be recorded the 1347 European import of the plague via a Genoese trading post in the Black Sea. High mortality precipitated a weakening in the balance of maritime powers, leading to political strife with Venice and outright war. After a failing alliance with France against Barbary pirates, Genoa became a satellite of Spain; a native son and heir to its vital maritime tradition, Christopher Columbus, sponsored the discovery of the Americas in 1492.

Ottoman era

After the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 the Byzantine forces in Gökçeada left the island. In the aftermath following the withdrawal, delegates from the island went to İstanbul for an audience with the Ottoman Emperor Fatih Sultan Mehmed to discuss terms allowing them to live harmoniously within the Ottoman Empire.

After the island became Ottoman soil in 1455 it was administered by Ottomans and Venetians at various times. During this period, and particularly during the reign of Kanuni Sultan Süleyman (1520-1566), the island became a foundation within the Ottoman Empire. Relations between the Ottomans and Venetians occasionally led to hostilities - for example, in June 1717 during the Turkish-Venetian War (1714-1718), a tough but ultimately fairly indecisive naval battle between a Venetian fleet, under Flangini, and an Ottoman fleet was fought near Imbros in the Aegean Sea (see Battle of Imbros (1717)). Nevertheless, the island's residents continued to live in relative peace and prosperity until the 20th century.

In 1912 during the First Balkan War, Greece invaded the island. After the signing of the Treaty of Athens in 1913 all of the Aegean islands except Bozcaada and Gökçeada were ceded to Greece.

First World War

In 1915, Imbros played an important role as a staging post for the allied Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, prior to and during the invasion of the Gallipoli peninsula. A field hospital, airfield and administrative and stores buildings were constructed on the island. In particular, many ANZAC (Australian and New Zealand Army Corps) soldiers were based at Imbros during the Gallipoli campaign, and the island was used as an air and naval base by ANZAC, English, and French forces against Turkey. On 20 January 1918, a naval action (see Battle of Imbros (1918)) took place in the Aegean near the island when an Ottoman squadron engaged a flotilla of the British Royal Navy.

Between Turkey and Greece

Between November 1912 and September 1923, Imbros, together with Tenedos, were under Greek administration. Both islands were overwhelmingly Greek, and in the case of Imbros the population was entirely Greek.[1]

Because of their strategic position near the Dardanelles, the western powers, particularly Britain, insisted at the end of the Balkan Wars in 1913 that the island should be retained by the Ottoman Empire when the other Aegean islands were ceded to Greece. However, the islands remained under Greek administration.

In 1920, the Treaty of Sèvres with the defeated Ottoman Empire granted the island to Greece. The Ottoman government, which signed but did not ratify the treaty, was overthrown by the new Turkish nationalist Government of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, based in Ankara. After the Greco-Turkish War ended in Greek defeat in Anatolia, and the fall of Lloyd George and his Middle Eastern policies, the western powers agreed to the Treaty of Lausanne with the new Turkish Republic, in 1923. This treaty made the island part of Turkey; but it guaranteed a special autonomous administrative status for Imbros and Tenedos to accommodate the Greeks, and excluded them from the population exchange that took place between Greece and Turkey, due to their presence there as a majority.[14]

However shortly after the legislation of "Civil Law" on 26 June 1927 (Mahalli Idareler Kanunu), the rights accorded to the Greek population of Imbros and Tenedos were revoked, in violation of the Lausanne Treaty. Thus, the island was demoted from an administrative district to a sub-district which resulted that the island was to be stripped of its local tribunals. Moreover, the members of the local council were obliged to have adequate knowledge of the Turkish language, which meant that the vast majority of the islanders were excluded. Furthermore, according to this law, the Turkish government retained the right to dissolve this council and in certain circumstances, to introduce police force and other officials consisted by non-islanders. This law also violated the educational rights of the local community and imposed an educational system similar to that followed by ordinary Turkish schools.[15]

The first concrete sign of Turkification policy was undertaken in 1946, where the Turkish authorities installed the first wave of Turkish settlers from the Black Sea region.[16] Massive scale persecution against the local Greek element started in 1961, as part of the Eritme Programmi operation that aimed at the elimination of Greek education and the enforcement of economic, psychological pressure and violence. Under these conditions the Turkish government approved the appropriation of the 90% of the cultivated areas of the island and the settlement of additional 6,000 ethnic Turks from mainland Turkey.[17] Also, Greeks on the island were targeted as part of an official policy that included allowing inmates at a jail built on the island to roam free and harass locals.[18] Additional population settlements from Anatolia occurred in 1973, 1984 and 2000. The state provided special credit opportunities and agricultural aid in kind to those who would decide to settle in the island.[19] On the other hand the indigenous Greek population being deprived of its means of production and facing hostile behaviour from the government and the newly arrived settlers, left its native land. The peak of this exodus was in 1974.[20]

On October 28 2010, the Greek cemetery of the island was desecrated and the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs condemned this action.[21]

Geography

- Çınarlı

- Çınarlı is the main town on Imbros, known as Panaghia Balomeni (Παναγία Μπαλωμένη) in Greek. Most of the settlements on Imbros were given Turkish names in 1926. Çınarlı is in the middle of the island; there is a small airport under construction nearby.

- Bademli köyü

- Older Greek name is Gliky (Γλυκύ). It is located to the northeast of the island, between Çınarlı town and Kaleköy/Kastro.

- Dereköy

- Older Greek name is Schoinoudi (Σχοινούδι). It is located at the center of the west side of island. Due to the emigration of the Greek population (largely to Australia and the USA; some to Greece and Istanbul before the 1970s), Dereköy is largely empty today. However, many people return on every 15 August for the festival of the Virgin Mary.

- Eşelek / Karaca köyü

It is located at the southeast of the island. It is an agricultural area that produces fruit and vegetables.

- Kaleköy

- Older name is Kastro (Κάστρο) (Latin and Greek for castle). Located on the north-eastern coast of island, there is an antique castle near the village. Kaleköy also has a small port which was constructed by the French Navy during the occupation in the First World War, and is now used for fishing-boats and yachts.

- Şahinkaya köyü

- It is located near Dereköy.

- Şirinköy

- It is located in the southwest of island.

- Tepeköy

- Older Greek name is Agridia (Αγριδιά). It is located in the north of the island, and is home to the largest Greek population on the island. An extinct volcano is located south of village which is the highest point of island.

- Uğurlu köyü

- It is located in the west of the island.

- Yeni Bademli köyü

- It is located at the center-northeast of island, near Bademli. It has many motels and pensions.

- Yenimahalle

- Older Greek name is Evlampio (Ευλάμπιο). It is located near Çınarlı Town on the road to Kuzulimanı port.

- Zeytinli köyü

- Older Greek name is Aghios Theodoros (Άγιος Θεόδωρος). Demetrios Archontonis, known as Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople, was born there on 29 February 1940.

- Others

- Yeni Bademli köyü, Eşelek / Karaca köyü, Şahinkaya köyü, Şirinköy and Uğurlu köyü were established after 1970.

Cittaslow

Gökçeada is one of the eight "cittaslows" of Turkey and is the second in being accepted as one, after Seferihisar.[22]

Places to see

- Aydıncık/Kefaloz (Kefalos) beach: Best location for windsurfing

- Kapıkaya (Stenos) beach:

- Kaşkaval peninsula / (Kaskaval): Scuba diving

- Kuzulimanı (Haghios Kyrikas): Ferryport with 24-hour ferries to Gelibolu–Kabatepe port and Çanakkale port.

- Mavikoy/Bluebay: The first national underwater park in Turkey. Scuba diving allowed for recreational purposes.

- Marmaros beach: Also has a small waterfall.

- Pınarbaşı (Spilya) beach: Longest (and most sandy) beach on the island.

Climate

| Climate data for Imbros | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

25 (77) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

24 (75) |

18 (64) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5 (41) |

5 (41) |

6 (43) |

11 (52) |

14 (57) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

21 (70) |

18 (64) |

13 (55) |

9 (48) |

6 (43) |

12.2 (53.8) |

| Avg. precipitation days | 11 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 12 | 15 | 99 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 105 | 123 | 171 | 219 | 295 | 333 | 366 | 350 | 267 | 195 | 132 | 93 | 2,649 |

| Source: Weatherbase[23] | |||||||||||||

Population

Greek population

The island was primarily inhabited by ethnic Greeks from ancient times through to approximately the middle of the twentieth century. Data dating from 1922 taken under Greek rule and 1927 data taken under Turkish rule showed a strong majority of Greek inhabitants on Imbros, and the Greek Orthodox Church had a strong presence on the island.

Article 14 of the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) exempted Imbros and Tenedos from the large-scale population exchange that took place between Greece and Turkey, and required Turkey to accommodate the local Greek majority and their rights:

The islands of Imbros and Tenedos, remaining under Turkish sovereignty, shall enjoy a special administrative organisation composed of local elements and furnishing every guarantee for the native non-Moslem population insofar as concerns local administration and the protection of persons and property. The maintenance of order will be assured therein by a police force recruited from amongst the local population by the local administration above provided for and placed under its orders.

However, the treaty provisions relating to administrative autonomy for Imbros and protections of minority populations never influenced the Turkish government."[24] The result was a significant decline in the Greek population of the island.[24]

A recent development whose long-term significance remains to be evaluated was the three-day visit of Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, a native of Imbros, (11–13 August 2011) in the course of which he met Stavros Lambrinidis, the foreign minister of Greece, apparently the first minister in office to visit the island, not officially though, since the Treaty of Lausanne (sources:SOP;Oecumenisme Informations no.420, December 2011).

Human rights

The Greek émigrés from Turkey assert numerous violations of the religious, linguistic, and economic rights guaranteed as matters of international concern by the Treaty, including freedom of the Orthodox religion and the right to practice the professions. Leaders of the Greek community in Turkey "voluntarily waived" these rights in 1926; but the Treaty provides (Article 44) that these rights can only be modified by the consent of the majority of the Council of League of Nations. The émigrés assert that the signatures to the waivers were obtained by orders of the police, and that Avrilios Spatharis and Savvas Apostologlou, who refused to sign, were imprisoned. The Greek government appealed this action to the Council and was upheld, but Turkey has not complied.

In addition, the following grievances apply particularly to Imbros:

- In 1923, Turkey dismissed the elected government of the island, and installed mainlanders. 1,500 Imbriots who had taken refuge from the Turkish War of Independence on Lemnos and in Thessalonica were denied the right to return, as undesirables and their property was confiscated.[25]

- In 1927, the system of local administration on Imbros was abolished, and the Greek schools closed. In 1952-3, the Greek Imbriots were permitted to build new ones, closed again in 1964.[26]

- In 1943, Turkey arrested the Metropolitan of Imbros and Tenedos with other Orthodox clerics. They also confiscated the lands on Imbros belonging to the monasteries of Great Lavra and Koutloumousiou on Mount Athos, expelled the tenants, and installed settlers; when the Mayor of Imbros and four village elders protested, they were arrested and sent to the mainland.

- Between 1964 and 1984, almost all the usable land on Imbros had been expropriated, for inadequate compensation, for an army camp, a minimum-security prison, reforestation projects, a dam project, and a national park.[26]

- Nicholas Palaiopoulos, a town councilor, was arrested and imprisoned in 1966 for complaining to the Greek Ambassador on the latter's visit to Imbros; he, together with the Mayor of Imbros and 20 others, was imprisoned again in 1974.

- The old Cathedral at Kastro (Kaleköy) was desecrated on the night of the Turkish landing on Cyprus in 1974 ; the present Cathedral was looted in March 1993; criminal activities have included a number of rapes and murders, officially blamed on convicts and soldiers, but none of them has been solved.

- In July 1993, the Turkish National Security began a program to settle mainland Turks on Imbros (and Tenedos).

All of these events have led to the Greeks emigrating from both islands. Before 1964, the population of Imbros was 7,000 Greeks, and 200 mainland Turkish officials; by 1970 the Greeks were a minority at 40% of the population, and there remains only a very small Greek community on Imbros today, comprising several hundred mostly elderly people. Most of the former Greeks of Imbros and Tenedos are in diaspora in Greece, the United States, and Australia.[27]

Population change in Imbros

| Town and villages[29][30] | 1927 | 1970 | 1975 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1997 | 2000 | ||||||||

| Çınarlı (Panaghia Balomeni) | - | - | 3578 | 615 | 3806 | 342 | 4251 | 216 | 767 | 70 | 721 | 40 | 553 | 26 | 503 | 29 |

| Bademli (Gliky) | - | - | 66 | 144 | 1 | 57 | 40 | 1 | 13 | 34 | 29 | 22 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 13 |

| Dereköy (Shinudy) | - | - | 73 | 672 | 391 | 378 | 319 | 214 | 380 | 106 | 99 | 68 | 82 | 40 | 68 | 42 |

| Eşelek | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 152 | - |

| Fatih | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3962 | 45 | 4284 | 32 | 4135 | 21 | 4180 | 25 |

| Kaleköy (Kastro) | - | - | 38 | 36 | 24 | - | - | 128 | 94 | - | 105 | - | 90 | - | 89 | - |

| Şahinkaya | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 168 | - | 107 | - | 86 | - |

| Şirinköy | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 189 | - |

| Tepeköy (Agridia) | - | - | 3 | 504 | 4 | 273 | 2 | 193 | 1 | 110 | 75 | 2 | 2 | 39 | 2 | 42 |

| Uğurlu | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 460 | - | 490 | - | 466 | - | 401 | - |

| Yenibademli | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 416 | - | 660 | - | 628 | - | 581 | - |

| Yenimahalle (Evlampio) | - | - | 182 | 143 | 162 | 121 | 231 | 81 | 359 | 59 | 970 | 27 | 2240 | 25 | 2362 | 27 |

| Zeytinli (Aghios Theodoros) | - | - | 30 | 507 | 15 | 369 | 36 | 235 | 72 | 162 | 25 | 130 | 12 | 82 | 12 | 76 |

| TOTAL | 157 | 6555 | 3970 | 2621 | 4403 | 1540 | 4879 | 1068 | 6524 | 586 | 7626 | 321 | 8330 | 248 | 8640 | 254 |

Culture

A Turkish documentary of 2013, "Rüzgarlar" (Winds), by Selim Evci, is focused on the discriminative government policies of the 1960s against the Greek population.[31]

Another Turkish movie film "Dedemin İnsanları" (The People of my Grandfather), is based on the exchange of population between Turkey and Greece in 1923. Among other places, some scenes were filmed in Imbros.[32]

Notable people from Imbros

- Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople, spiritual leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- Michael Critobulus 15th century politician and historian.

- Archbishop Iakovos of America, Primate of the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America (1959-1996).

See also

- Treaty of Lausanne

- Greco-Turkish relations

- Treaty of Sèvres

- Tenedos

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Alexis Alexandris, "The Identity Issue of The Minorities In Greece An Turkey", in Hirschon, Renée (ed.), Crossing the Aegean: An Appraisal of the 1923 Compulsory Population Exchange Between Greece and Turkey, Berghahn Books, 2003, p. 120

- ↑ "Hüzün Adası: İmroz", Yeniçağ, July 12, 2007

- ↑ Gökçeada", from Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- ↑ "::Türkiye Ýstatistik Kurumu Web sayfalarýna Hoţ Geldiniz::". Tuik.gov.tr. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ Hurriyet Daily News. "Greeks look to revive identity on Gökçeada", August 22, 2011.

- ↑ Mohammadi, A., Ehteshami, A. "Iran and Eurasia" Garnet&Ithaca Press, 2000, 221 pages. p. 192

- ↑ Homer, The Iliad Book XIII.

- ↑ Homer, The Iliad, Book XXI.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, Book V.

- ↑ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book VII.

- ↑ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Books III, IV, and V.

- ↑ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book VIII.

- ↑ Oxford Classical Dictionary: "Imbros"

- ↑ See link to the text of the Treaty of Lausanne, below

- ↑ Alexandris, Alexis (1980). Imbros and Tenedos:: A Study of Turkish Attitudes Toward Two Ethnic Greek Island Communities Since 1923. Pella Publishing Company. p. 21.

- ↑ Babul, 2004: 5

- ↑ Λιμπιτσιούνη, Ανθή Γ. "Το πλέγμα των ελληνοτουρκικών σχέσεων και η ελληνική μειονότητα στην Τουρκία, οι Έλληνες της Κωνσταντινούπολης της Ίμβρου και της Τενέδου". Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης. pp. 98–99.

- ↑ "Turkish public unaware of truth of Imbros: Patriarch". Hürriyet Daily News. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012. "According to Feryal Tansuğ, a historian at Istanbul’s Bahçeşehir University, who compiled the book “İmroz Rumları, Gökçeada Üzerine” (Rums of Imbros, on Gökçeada), non-Muslims on the island were targeted as part of an official policy that included allowing inmates at a jail built on the island to roam free and harass locals."

- ↑ Babul, 2004: 5-6

- ↑ Babul, 2004: 6

- ↑ "Turkish public unaware of truth of Imbros: Patriarch". Hürriyet Daily News. 31 October 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Turkey - Cittaslow International". www.cittaslow.org. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ "Imroz, Turkey Travel Weather Averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Human Rights Watch (1992). Denying Human Rights and Ethnic Identity: The Greeks in Turkey. p. 27.

- ↑ Libitsiouni, Anthi. "Το πλέγμα των ελληνοτουρκικών σχέσεων και η ελληνική μειονότητα στην Τουρκία,. Οι Έλληνες της Κωνσταντινούπολης, της Ίμβρου και της Τενέδου, 1955-1964" (PDF). University of Thessaloniki. pp. 108–109. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights. "Gökçeada (Imbros) and Bozcaada (Tenedos): preserving the bicultural character of the two Turkish islands as a model for co-operation between Turkey and Greece in the interest of the people concerned" (PDF). Parliamentary Assembly Assemblée parlementaire. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ↑ Struggle for Justice, pp.33-73; they ascribe the resettlement program to an article in the Turkish magazine "Nokta".

- ↑ Babul, Elif. "Belonging to Imbros: Citizenship and Sovereignty in the Turkish Republic" (PDF). Bogazici University. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ↑ http://www.gokceada.bel.tr/ Gökçeada Municipality official page

- ↑ Alanur Çavlin Bozbeyoğlu, Işıl Onan, "Changes in the demographic characteristics of Gökçeada"

- ↑ "ΒΙΝΤΕΟ: Τα τουρκικά εγκλήματα στην Ίμβρο, αποκαλύπτει τουρκική ταινία". onalert.gr. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ from Christy dim 9 months ago not yet rated (2012-05-31). "Dedemin İnsanları - My Grandfather's people (with english subs) on Vimeo". Vimeo.com. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

Further reading

- The struggle for justice : 1923-1993 : 70 years of Turkish provocation and violations of the Treaty of Lausanne : a chronicle of human rights violations; Citizen's Association of Constantinople-Imvros-Tenedos-Eastern Thrace of Thrace. Komotini (1993)

- "Greeks look to revive identity on Gökçeada" in Hürriyet Daily News, 22 August 2011.

- Papers presented to the II. National Symposium on the Aegean Islands, 2–3 July 2004, Gökçeada, Çanakkale.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gökçeada. |

- Official website of the Gökçeada District

- Official website of the Gökçeada Municipality

- Gökçeada Airport

- Gökçeada in "I was in Turkey.com"

- The Greeks of Imbros, video of the book İmroz Rumları / Gökçeada Üzerine, a film directed by Yannis Katomeris, ISBN 978-605-5419-75-2

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||