Ice giant

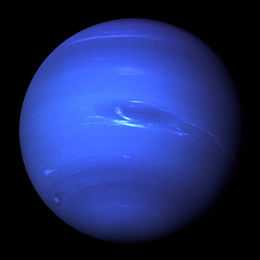

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of substances heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System, Uranus and Neptune. They consist of only about 20% hydrogen and helium in mass, as opposed to the gas giants (Jupiter and Saturn), which are both more than 90% hydrogen and helium in mass. In the 1990s, it was realized that Uranus and Neptune are a distinct class of giant planet, separate from the other giant planets. They have become known as ice giants because their constituent compounds were ices when they were primarily incorporated into the planets during their formation, either directly in the form of ices or trapped in water ice. There is, however, very little solid ice remaining within the ice giants today.[1]

Terminology

In 1952, science fiction writer James Blish coined the term gas giant to refer to the large non-terrestrial planets of the Solar System. However, in the 1990s, the compositions of Uranus and Neptune were discovered to be significantly different from those of Jupiter and Saturn. They are primarily composed of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, constituting a separate type of giant planet altogether. Because Uranus and Neptune, during their formations, incorporated their material as either ices or gas trapped in water ice, the term ice giant came into use.[1]

Today, there is very little ice left in Uranus and Neptune. H2O primarily exists as supercritical fluid at the temperatures and pressures within them.[1]

Formation

Modelling the formation of the terrestrial and gas giants is relatively straightforward and uncontroversial. The terrestrial planets of the Solar System are widely understood to have formed through collisional accumulation of planetesimals within the protoplanetary disc. The gas giants—Jupiter, Saturn, and their extrasolar counterpart planets—are thought to have formed after solid cores around 10 Earth masses (M⊕) formed through the same process and then accreted gas envelopes from the surrounding solar nebula over the course of several million years (Ma) or more.[2]

The formation of Uranus and Neptune through a similar process of core accretion is far more problematic. The escape velocity for the small protoplanets about 20 astronomical units (AU) from the centre of the Solar System would have been comparable to their relative velocities. Such bodies crossing the orbits of Saturn or Jupiter would have been liable to be sent on hyperbolic trajectories ejecting them from the system. Such bodies, being swept up by the gas giants, would also have been likely to just be accreted into the larger planets or thrown into cometary orbits.[2]

In spite of the trouble modelling their formation, many ice giant candidates have been observed orbiting other stars, since 2004. This indicates that they may be common in the Milky Way.[1]

Migration

Considering the orbital challenges of protoplanets 20 AU or more from the centre of the Solar System would experience, a simple solution is that the ice giants formed between the orbits Jupiter and Saturn before being gravitationally scattered outward to their now more distant orbits.[2]

Disk instability

Gravitational instability of the protoplanetary disk could also possibly produce several gas giant protoplanets out to distances of up to 30 AU. Slightly-higher-density regions in the disk could lead to the formation of clumps that eventually collapse to planetary densities.[2] A disk with even marginal gravitational instability could yield protoplanets between 10 and 30 AU over one thousand years (ka). This is much shorter than the 100,000 to 1 million years required to produce protoplanets through core accretion of the cloud and could make it viable in even the shortest-lived disks, which exist for only a few million years.[3]

A problem with this model is determining what kept the disk stable prior to the instability. There are several possible mechanisms allowing gravitational instability to occur during disk evolution. A close encounter with another protostar could provide a gravitational kick to an otherwise stable disk. A disk evolving magnetically is likely to have magnetic dead zones, due to varying degrees of ionization, where mass moved by magnetic forces could pile up, eventually becoming marginally gravitationally unstable. A protoplanetary disk may simply accrete matter slowly, causing relatively short periods of marginal gravitational instability and bursts of mass collection, followed by periods where the surface density drops below what is required to sustain the instability.[3]

Photoevaporation

Observations of photoevaporation of protoplanetary disks in the Orion Trapezium Cluster by extreme ultraviolet (EUV) radiation emitted by θ1 Orionis C suggests another possible mechanism for the formation of ice giants. Multiple-Jupiter-mass gas-giant protoplanets could have rapidly formed due to disk instability before having the majority of their hydrogen envelopes stripped off by intense EUV radiation from a nearby massive star.[2]

In the Carina Nebula, EUV fluxes are approximately 100 times higher than in Trapezium's Orion Nebula. Protoplanetary disks are present in both nebulae. Higher EUV fluxes make this an even more likely possibility for ice-giant formation. The stronger EUV would increase the removal of the gas envelopes from the protoplanets before they could collapse sufficiently to resist further loss.[2]

Characteristics

The ice giants represent one of two fundamentally different categories of giant planets present in the Solar System. The other group being the more-familiar gas giants, which are composed of more than 90% hydrogen and helium (by mass). Their hydrogen is thought to extend all the way down to their small rocky cores, where hydrogen molecular ion transitions to metallic hydrogen under the extreme pressures of hundreds of gigapascals (GPa).[1]

The ice giants are primarily composed of heavier elements. Based on the abundance of elements in the universe, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur are most likely. Although the ice giants also have hydrogen envelopes, these are much smaller. They account for less than 20% of their mass. Their hydrogen also never reaches the depths necessary for the pressure to create metallic hydrogen.[1] These envelopes nevertheless limit observation of the ice giants' interiors, and thereby the information on their composition and evolution.[4]

Atmosphere and weather

The gaseous outer layers of the ice giants exhibit phenomena with several similarities to those of the gas giants. This includes long-lived, high-speed equatorial winds, polar vortices, large-scale circulation patterns, and complex chemical processes driven by ultraviolet radiation from above and mixing with the lower atmosphere.[1]

Studying the ice giants' atmospheric pattern also gives insights into atmospheric physics. Their compositions promote different chemical processes and they receive far less sunlight in their distant orbits than any other planets in the Solar System (increasing the relevance of internal heating on weather patterns).[1]

The largest visible feature on Neptune is the recurring Great Dark Spot. It forms and dissipates every few years, as opposed to the similarly-sized Great Red Spot of Jupiter, which has persisted for centuries. Neptune emits the most internal heat per unit of absorbed sunlight, a ratio of approximately 2.6. Saturn, the next-highest emitter, only has a ratio of about 1.8. Uranus emits the least amount of heat, ten times less than Neptune. It is suspected that this may be related to its extreme 98˚ axial tilt. This causes its seasonal patters to be very different from that of any other planet in the Solar System.[1]

There are still no complete models explaining the atmospheric features observed in the ice giants.[1] Understanding these features will help elucidate how the atmospheres of giant planets in general function.[5] Consequently, such insights could help scientist better predict the atmospheric structure and behaviour of giant exoplanets discovered to be very close to their host stars (pegasean planets) and exoplanets with masses and radii between that of the giant and terrestrial planets found in this solar system.[4]

Interior

Because of their large sizes and low thermal conductivities, the planetary interior pressures range up to several hundred GPa and temperatures of several thousand kelvins (K).[6]

In March 2012, it was found that the compressibility of water used in ice-giant models could be off by one third.[7] This value is important for modeling ice giants, and has a ripple effect on understanding them.[7]

Magnetic fields

The magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune are both unusually displaced and tilted.[8] Their field strengths are intermediate between those of the gas giants and those of the terrestrial planets, being 50 and 25 times that of Earth's, respectively.[8] Their magnetic fields are believed to originate in an ionized convecting molten-ice mantle.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Hofstadter 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Boss 2003, § 1.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Boss 2003, § 2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hofstadter 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Hofstadter 2011, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Nellis 2012.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The Interiors of Ice Giant Planets (2012)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 The nature and origin of planetary magnetic fields

Bibliography

- Boss, Alan P. (December 2003). "Rapid Formation of Outer Giant Planets by Disk Instability". The Astrophysical Journal 599: 577–581. doi:10.1086/379163.

- Hofstadter, Mark (2011), "The Atmospheres of the Ice Giants, Uranus and Neptune", White Paper for the Planetary Science Decadal Survey (US National Research Council), retrieved 18 January 2015

- Nellis, William (February 2012). "Viewpoint: Seeing Deep Inside Icy Giant Planets". Physics 5 (25). doi:10.1103/Physics.5.25.

External links

| Look up ice giant in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Sandia experiments may force revision of astrophysical models of the universe - Sandia Labs

- Viewpoint: Seeing Deep Inside Icy Giant Planets

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||