I'm Not There

| I'm Not There | |

|---|---|

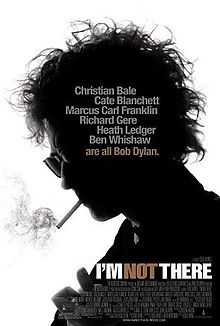

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Todd Haynes |

| Produced by |

Christine Vachon John Goldwyn |

| Written by |

Todd Haynes Oren Moverman |

| Starring |

Christian Bale Cate Blanchett Marcus Carl Franklin Richard Gere Heath Ledger Ben Whishaw |

| Narrated by | Kris Kristofferson |

| Music by | Bob Dylan |

| Cinematography | Edward Lachman |

| Edited by | Jay Rabinowitz |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | The Weinstein Company |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 135 minutes |

| Country |

Germany United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20 million (est.) |

| Box office | $11,523,779 |

I'm Not There is a 2007 biographical musical film directed by Todd Haynes, inspired by the life and music of American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan. Six actors depict different facets of Dylan's public personas: Christian Bale, Cate Blanchett, Marcus Carl Franklin, Richard Gere, Heath Ledger, and Ben Whishaw. At the start of the film, a caption reads: "Inspired by the music and the many lives of Bob Dylan". Apart from the song credits, this is the only mention of Bob Dylan in the film.

The film tells its story using non-traditional narrative techniques, intercutting the storylines of seven different Dylan-inspired characters. The title of the film is taken from the 1967 Dylan Basement Tape recording of "I'm Not There", a song that had not been officially released until it appeared on the film's soundtrack album. The film received a generally favorable response, and appeared on several top ten film lists for 2007, topping the lists for The Village Voice, Entertainment Weekly, Salon and The Boston Globe. Particular praise went to Cate Blanchett for her performance, culminating in a Volpi Cup from the Venice Film Festival, the Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actress, along with an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress nomination.

Plot

The Production Notes published by distributor The Weinstein Company, give this summary: "I'm Not There is a film that dramatizes the life and music of Bob Dylan as a series of shifting personae, each performed by a different actor—poet, prophet, outlaw, fake, star of electricity, rock and roll martyr, born-again Christian—seven identities braided together, seven organs pumping through one life story."[1] In the opening titles of the film, a caption reads: "Inspired by the music and the many lives of Bob Dylan".[2] Besides the song credits, this is the only time Dylan's name appears in the film.

The film begins with Jude Quinn (Cate Blanchett) walking onto a stage to perform, before cutting to him riding a motorcycle which crashes—a reference to Dylan having a serious motorcycle accident in 1966.[3] The film then cuts to Quinn's body on a mortuary slab as an autopsy begins.

Woody (Marcus Carl Franklin), an 11-year old African American boy, is seen with a guitar which carries the label "This machine kills fascists" as he travels the country. (Folk singer Woody Guthrie had an identical label on his guitar.)[4] Woody befriends the African-American Arvin family, who give him food and hospitality, and Woody in turn performs Bob Dylan's 1965 song "Tombstone Blues", accompanied by Richie Havens (as Old Man Arvin). At dinner, Mrs. Arvin advises Woody: "Live your own time, child, sing about your own time".

Later that night, Woody leaves the Arvins' home and catches a ride on a train, where a group of hobos try to rob him. He jumps from the train into a river, where a white couple rescue him and take him to their home. They receive a phone call from a juvenile correction center in Minnesota from which Woody had escaped. The phone call prompts Woody's swift departure, and he takes a Greyhound bus to Greystone Park Hospital in New Jersey, where he visits (the real) Woody Guthrie, leaving flowers at Guthrie's bedside and playing his guitar.

Ben Whishaw plays a young man with the same name as the nineteenth century French poet Arthur Rimbaud. Arthur is only seen in an interrogation room where he gives cryptic answers to (unseen) interrogators.

Christian Bale plays Jack Rollins, a young folk singer, whose story is framed as a documentary and told by interviewees such as fictional folk singer Alice Fabian—described by some critics as a Joan Baez-like figure[5][6]—played by Julianne Moore. Rollins is praised by folk fans who refer to his songs as anthems and protest songs, whereas Jack himself calls them finger-pointing songs. When Rollins accepts the "Tom Paine Award" from a civil rights organization, a drunken Rollins insults the audience and claims that he saw something of himself in JFK's assassin Lee Harvey Oswald. (Rollins's speech quotes from a speech Dylan made when receiving the Tom Paine Award from the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee in December 1963.)[7]

Bale also plays Pastor John, a Born Again Christian preacher, who appears to be the Jack Rollins character several years later, after he has travelled to California and joined a church. He has become a preacher and is seen declaring his faith to fellow church members and performing "Pressing On"—a song written and performed by Dylan on his 1980 gospel album Saved.

Heath Ledger plays Robbie Clark, an actor who is starring in a biopic about the life of Jack Rollins (the folk singer played by Christian Bale). We see how Robbie met his French artist wife Claire, played by Charlotte Gainsbourg, in a Greenwich Village diner and they fell in love. (The scene in which Robbie and Claire run romantically through the streets of New York re-enacts the cover of the 1963 album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan which depicts Dylan arm in arm with his then-girlfriend Suze Rotolo in Greenwich Village.)[8] Robbie and Claire's relationship deteriorates when Claire glimpses Robbie womanising at a party. As their marriage ends, Robbie and Claire fight over custody of their children. We see Robbie taking his daughters on a trip while archival clips show Henry Kissinger and Le Duc Tho signing the Paris Peace Accords. (Bob Dylan was divorced from his first wife, Sara Dylan, on June 29, 1977 and the divorce involved court battles over the custody of their children.)[9] In his production notes, Haynes wrote that Robbie and Claire's relationship is "doomed to a long stubborn protraction (not unlike Vietnam, which it parallels)."[6]

Cate Blanchett plays Jude Quinn, a character who, according to the Weinstein Production Notes, "closely follows Dylan's mid-sixties adventures."[1] Jude is seen at a folk festival performing a rock version of "Maggie's Farm" to outraged folk music fans. (Dylan performed this song at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, which provoked booing and controversy.)[10] Jude is seen arriving at a press conference in London and answering questions. (Some of these questions are quotes from Dylan's KQED press conference in San Francisco on December 3, 1965.)[11][12] Jude's operations in London are supervised by his manager, Norman (who resembles Bob Dylan's 1960s manager Albert Grossman). In a surreal scene, Jude is seen gambolling at high speed in a park with the Beatles. (The speeded-up film echoes the style of Dick Lester's direction in A Hard Day's Night.)[13] Jude is then confronted by BBC cultural reporter, Keenan Jones, played by Bruce Greenwood (the name of this character echoes Dylan's song "Ballad of a Thin Man" with its chorus: "Something is happening here/ And you don't know what it is, do you Mr. Jones?").

Jude and his entourage meet poet Allen Ginsberg, played by David Cross, who suggests Jude may be "selling out" to God. Keenan Jones later asks Jude whether he cares about what he sings about every night, to which Jude replies, "How can I answer that if you've got the nerve to ask me?" and walks out of the interview. (Dylan makes a similar response to a reporter from Time magazine in D. A. Pennebaker's documentary about Dylan's 1965 English tour, Dont Look Back.)[14] The Dylan song "Ballad of a Thin Man" plays as Keenan Jones moves through a surreal episode in which he appears to act out the song's lyrics.[15] In concert, Jude performs "Ballad of a Thin Man", when one of his outraged fans shouts "Judas!" Jude replies "I don't believe you". (This scene re-enacts the "Judas!" shout at Dylan's Manchester concert on May 17, 1966. The moment is captured on Dylan's album Live 1966.)

Back in his hotel suite, Jude watches Keenan Jones on television reveal the true identity of Jude Quinn is "Aaron Jacob Edelstein". (In October 1963, Newsweek published a hostile profile of Dylan, revealing that he was originally named Robert Zimmerman, and implying that he had lied about his middle-class origins.)[16] Jude throws a party where the guests include the "queen of the underground" Coco Rivington (Michelle Williams), whom Jude insults. (The description of Rivington as "Andy's new bird" suggests this character is modeled on Edie Sedgwick, a socialite and actress within Andy Warhol's circle.)[13] Jude and Ginsberg later stand in front of a huge crucifix, while Jude shouts at the figure on the cross: "Why don't you do your early stuff?" After being whisked off in a car, Jude passes out, as "his dangerous game propels him into existential breakdown."[1]

Richard Gere portrays the outlaw Billy the Kid. Billy searches for his dog, Henry, and then meets his friend, Homer. As the people of the small town of Riddle celebrate Halloween, a funeral takes place and a band performs Dylan's Basement Tapes song "Goin' to Acapulco" (sung by Jim James with the band Calexico). Following the service, Pat Garrett (Bruce Greenwood – who earlier in the film played Keenan Jones, a journalist who had interrogated Jude Quinn) arrives and threatens the townspeople. Billy dons a mask to disguise himself and tells Garrett to clear out of Riddle County. Garrett orders the authorities to arrest Billy and he is taken to the county jail. Billy escapes from jail and hops a ride on a train, where he finds a guitar which reads "This Machine kills Fascists": the same guitar that Woody Guthrie played at the start of the film. Billy's final words are "People are always talking about freedom, the freedom to live a certain way without being kicked around. 'Course the more you live a certain way the less it feels like freedom. Me? I can change during the course of a day. When I wake I'm one person, when I go to sleep I know for certain I'm somebody else. I don't know who I am most of the time. It's like you got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room. There's no telling what can happen," which echoes remarks Dylan has made in interviews.[17]

The film ends with a close-up of the real Bob Dylan playing a harmonica solo during a live performance of "Mr. Tambourine Man".[13] The footage was shot by D. A. Pennebaker during Dylan's 1966 World Tour.[18]

Cast

- Marcus Carl Franklin as Woody. This character refers to Dylan's youthful obsession with folk singer Woody Guthrie.[19]

- Christian Bale as Jack Rollins and Pastor John. Jack Rollins portrays Dylan during his acoustic, 'protest' phase which includes The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan and The Times They Are a-Changin'. Pastor John embodies Dylan's "born-again" period when he recorded Slow Train Coming and Saved.

- Cate Blanchett as Jude Quinn. Quinn is a portrayal of Dylan in 1965–1966, when he controversially played electric guitar at the Newport Folk Festival, and toured the UK with a band and was booed.[20] This phase of Dylan's life was documented by D. A. Pennebaker in the film Eat the Document.[21]

- Richard Gere as Billy the Kid. Billy refers to Dylan playing the role of Alias in Sam Peckinpah's 1973 western Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.[22][23]

- Heath Ledger as Robbie Clark, an actor who portrays Jack Rollins in a biopic and becomes as famous as the person he portrays; he experiences the stresses of a disintegrating marriage, reflecting Dylan's personal life around the time of 1975's Blood on the Tracks.

- Ben Whishaw as Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud is depicted as a man being questioned and responding with quotes from Dylan's interviews and writings. Dylan wrote in his autobiography Chronicles that he was influenced by Rimbaud's outlook.[24]

The above seven characters represent different aspects of Bob Dylan's life and music.[2][6]

- Charlotte Gainsbourg as Claire, wife of Robbie Clark (a representation of Sara Dylan and Suze Rotolo)[6][13]

- David Cross as Allen Ginsberg

- Eugene Brotto as Peter Orlovsky

- Bruce Greenwood as Keenan Jones, a fictional reporter who investigates Jude Quinn, and Pat Garrett, nemesis of Billy the Kid

- Julianne Moore as Alice Fabian, a singer who resembles Joan Baez[5]

- Michelle Williams as Coco Rivington, who resembles Andy Warhol star Edie Sedgwick[13]

- Mark Camacho as Norman, the manager of Jude Quinn (a representation of Dylan's manager until 1970, Albert Grossman)

- Benz Antoine as Bobby Seale, the Black Panther leader, and Rabbit Brown

- Craig Thomas as Huey Newton, the Black Panther leader

- Richie Havens as Old Man Arvin

- Kim Roberts as Mrs. Arvin

- Kris Kristofferson as The Narrator

- Don Francks as Hobo Joe

- Vito DeFilippo and Susan Glover as Mr. and Mrs. Peacock, a middle-class couple who take "Woody Guthrie" in after a near-drowning incident

- Paul Spence as Homer, Billy the Kid's friend.

Production

Development

Todd Haynes and his producer, Christine Vachon, approached Bob Dylan's manager, Jeff Rosen, to obtain permission to use Dylan's music and to fictionalize elements of Dylan's life. Rosen suggested that Haynes should send a one-page synopsis of his film for submission to Dylan. Rosen advised Haynes not to use the word 'genius'.[6] The page Haynes submitted began with a quote from Arthur Rimbaud: "I is someone else", and then continued:

- If a film were to exist in which the breadth and flux of a creative life could be experienced, a film that could open up, as opposed to consolidating, what we think we already know walking in, it could never be within the tidy arc of a master narrative. The structure of such a film would have to be a fractured one, with numerous openings and a multitude of voices, with its prime strategy being one of refraction, not condensation. Imagine a film splintered between seven separate faces — old men, young men, women, children — each standing in for spaces in a single life.[6]

Dylan gave Haynes permission to proceed with his project. Haynes developed his screenplay with writer Oren Moverman. In the course of writing, Haynes has acknowledged that he became uncertain whether he could successfully carry off a film which deliberately confused biography with fantasy in such an extreme way. According to the account of the film that Robert Sullivan published in the New York Times: "Haynes called Jeff Rosen, Dylan’s right hand, who was watching the deal-making but staying out of the scriptwriting. Rosen, he said, told him not to worry, that it was just his own crazy version of what Dylan is."[6]

In a comment on why six actors were employed to portray different facets of Dylan's personality, Haynes wrote:

The minute you try to grab hold of Dylan, he's no longer where he was. He's like a flame: If you try to hold him in your hand you'll surely get burned. Dylan's life of change and constant disappearances and constant transformations makes you yearn to hold him, and to nail him down. And that's why his fan base is so obsessive, so desirous of finding the truth and the absolutes and the answers to him – things that Dylan will never provide and will only frustrate.... Dylan is difficult and mysterious and evasive and frustrating, and it only makes you identify with him all the more as he skirts identity.[25]

A further Dylan-based character named Charlie, based on Charlie Chaplin, was dropped before filming began. Haynes described him as "a little tramp, coming to Greenwich Village and performing feats of magic and being an arbiter of peace between the beats and the folkies."[26]

Filming

Principal photography for the film took place in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.[6] Music festival scenes were filmed in Chambly, Quebec in the summer of 2006.[27]

Music

The film features numerous songs by Dylan, performed by Dylan and also recordings by other artists. The songs feature as both foreground—performed by artists on camera (e.g. "Goin' to Acapulco", "Pressing On")—and background accompaniment to the action. A notable non-Dylan song in the movie is "(I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone" by The Monkees, which plays in the background of a party scene set in London.

Release

The film premiered at the 34th Telluride Film Festival on August 31, 2007. It opened in theaters in Italy and played the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2007. It opened in limited release in the United States and Canada in November, and was released in Australia on Boxing Day 2007. It was rated R by the Motion Picture Association of America for language, some sexuality, nudity and drug use.

Home media

I'm Not There was released on DVD as a 2-disc special edition on May 6, 2008.[28] The DVD special features include audio commentary from Haynes, deleted scenes, featurettes, a music video, audition tapes for certain cast members, trailers, and a Bob Dylan filmography and discography.[28]

Reception

Critical response

I'm Not There received generally positive reviews from critics. The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reported that 77% of critics gave the film positive reviews, based on 141 reviews.[29] Metacritic reported the film had an average score of 73 out of 100, based on 35 reviews.[30]

Writing in The Chronicle of Higher Education, critic Anthony DeCurtis said that casting six different actors, including a woman and an African-American child, to play Dylan was "a preposterous idea, the sort of self-consciously 'audacious'—or reassuringly multi-culti—gambit that, for instance, doomed the Broadway musical based on the life and music of John Lennon. Yet in I'm Not There, the strategy works brilliantly." He especially praised Blanchett:

| “ | Her performance is a wonder, and not simply because, as Jude Quinn, she inhabits the twitchy, amphetamine-fired Dylan of 1965–66 with unnerving accuracy. Casting a woman in this role reveals a dimension to the acerbic Dylan of this era that has rarely been noted. Even as she perfectly mimics every jitter, sneer, and caustic put-down, Blanchett's translucent skin, delicate fingers, slight build, and pleading eyes all suggest the previously invisible vulnerability and fear that fueled Dylan's lacerating anger. It's hard to imagine that any male actor, or any less-gifted female actor for that matter, could have lent such rich texture to the role.[31] | ” |

Several reviewers praised Blanchett's performance as the mid-60s Dylan. Newsweek magazine described Blanchett as "so convincing and intense that you shrink back in your seat when she fixes you with her gaze."[32] The Charlotte Observer called Blanchett "miraculously close to the 1966 Dylan."[33] The film won the Grand Jury Prize and Best Actress honors for Blanchett at the 64th Venice International Film Festival.[34] Blanchett also won the Golden Globe Award for her performance, in addition to several critics awards. She was nominated for a Screen Actors Guild Award and an Academy Award.

Todd McCarthy, writing in the film trade magazine Variety, concluded that the film was well-made, but was ultimately a speciality event for Dylan fans, with little mainstream appeal. He wrote: "Dylan freaks and scholars will have the most fun with I'm Not There, and there will inevitably be innumerable dissertations on the ways Haynes has both reflected and distorted reality, mined and manipulated the biographical record and otherwise had a field day with the essentials, as well as the esoterica, of Dylan's life. All of this will serve to inflate the film's significance by ignoring its lack of more general accessibility. In the end, it's a specialists' event."[2]

For Roger Ebert, the film was enjoyable cinematically, yet never sought to resolve the enigmas of Dylan's life and work: "Coming away from I'm Not There, we have, first of all, heard some great music (Dylan surprisingly authorized use of his songs both on his own recordings and performed by others). We've seen six gifted actors challenged by playing facets of a complete man. We've seen a daring attempt at biography as collage. We've remained baffled by the Richard Gere cowboy sequence, which doesn't seem to know its purpose. And we have been left not one step closer to comprehending Bob Dylan, which is as it should be."[5]

Dylan's response

In September 2012, Dylan commented on I'm Not There in an interview published in Rolling Stone. When journalist Mikal Gilmore asked Dylan whether he liked the film, he responded: "Yeah, I thought it was all right. Do you think that the director was worried that people would understand it or not? I don't think he cared one bit. I just think he wanted to make a good movie. I thought it looked good, and those actors were incredible."[35]

Top ten lists

The film appeared on several critics' lists of the top ten films of 2007.

|

|

Accolades

- Academy Awards:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, nominee)[38]

- 61st British Academy Film Awards

- Best Actress in a Supporting Role (Cate Blanchett, nominee)

- Broadcast Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, nominee)

- Central Ohio Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Chicago Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Golden Globe Awards:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Independent Spirit Awards

- Robert Altman Award (cast and crew, winner)

- Best Director (Todd Haynes, nominee)

- Best Film (nominee)

- Best Supporting Actor (Marcus Carl Franklin, nominee)

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Las Vegas Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Los Angeles Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, runner-up)

- New York Film Critics Circle:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, runner-up)

- New York Film Critics Online:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- National Society of Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Nilsson Awards for Film

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)

- Best Cinematography

- Best Compiled Soundtrack

- Satellite Awards:

- Best Actress – Comedy or Musical (Cate Blanchett, nominee)

- Screen Actors Guild (SAG):

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, nominee)

- Southeastern Film Critics:

- Best Supporting Actress (Cate Blanchett, runner-up)

- Venice Film Festival:

- CinemAvvenire Award – Best Film (winner)

- Golden Lion (Todd Haynes, nominee)

- Special Jury Prize (Todd Haynes, winner)

- Volpi Cup Best Actress (Cate Blanchett, winner)[39]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 The Weinstein Company 2007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 McCarthy 2007

- ↑ Heylin 2003, pp. 266–267

- ↑ Gray 2006, pp. 287–289

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Ebert 2007

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Sullivan 2007

- ↑ Part of Dylan's speech went: "There's no black and white, left and right to me any more; there's only up and down and down is very close to the ground. And I'm trying to go up without thinking of anything trivial such as politics." (Shelton 1986, pp. 200–205)

- ↑ "NYC Album Art: The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan". Gothamist. 2006-04-18. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Gray, pp. 198–200

- ↑ Unterberger 2007

- ↑ Heylin 1996, p. 87

- ↑ Dylan's 1965 press conference reproduced in: Hedin (ed.), 2004, Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader, pp. 51–58.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Hoberman 2007

- ↑ Pennebaker 2006, p. 128

- ↑ "You walk into the room/ With your pencil in your hand/ You see somebody naked / And you say: 'Who is that man?'"

- ↑ Heylin 2003, pp. 129–130

- ↑ In his 1997 interview with David Gates of Newsweek, Dylan said: "I don't think I'm tangible to myself. I mean, I think one thing today and I think another thing tomorrow. I change during the course of a day. I wake and I'm one person, and when I go to sleep I know for certain I'm somebody else. I don't know who I am most of the time. It doesn't even matter to me." (Gates 1997)

- ↑ "I'm Not There Question". Expectingrain.com. October 21, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- ↑ Dylan 2004, pp. 243–246

- ↑ Shelton 1986, pp. 301–304

- ↑ Lee 2000, pp. 40–60

- ↑ "Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid". IMDb.com. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ↑ C. P. Lee wrote: "In Garrett's ghost-written memoir, The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid, published within a year of Billy's death, he wrote that 'Billy's partner doubtless had a name which was his legal property, but he was so given to changing it that it is impossible to fix on the right one. Billy always called him Alias.'" (Lee 2000, pp. 66–67)

- ↑ Dylan 2004, p. 146

- ↑ "Haynes in Weinstein Company press notes for "I'm Not There", quoted in Footnote fetishism & "I'm Not There" by Jim Emerson". Jim Emerson's scanners::blog. 2007-10-10.

- ↑ Male 2007

- ↑ Hardy 2006

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Gibron 2008

- ↑ "I'm Not There Movie Reviews, Pictures – Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "I'm Not There (2007): Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 2008-05-19.

- ↑ The Chronicle of Higher Education, November 23, 2007, p.15

- ↑ Gates 2007

- ↑ Lawrence Toppman, "Everybody's 'There' except Bob D." from The Charlotte Observer, November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Blanchett wins top Venice award

- ↑ Gilmore 2012

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 36.7 36.8 36.9 36.10 36.11 36.12 36.13 36.14 36.15 36.16 Metacritic: 2007 Film Critic Top Ten Lists

- ↑ Travers 2007

- ↑ Oscar Legacy: The 80th Academy Awards (2008) Nominees and Winners

- ↑ Coppa Volpi for best actors since 1935

References

- "Blanchett wins top Venice award". BBC News Online. 2007-09-08. Retrieved 2007-09-08.

- "Coppa Volpi for best actors since 1935". La Biennale di Venezia. Retrieved 2014-03-25.

- Dylan, Bob (2004). Chronicles: Volume One. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-2815-4.

- Ebert, Roger (2007-11-21). "I'm Not There". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- Gates, David (October 6, 1997). "Dylan Revisited". Newsweek. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- Gates, David (2007-11-07). "'Full-on Rave' for Dylan Film". Newsweek. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- Gibron, Bill (2008-05-07). "I'm Not There: Two-Disc Collector's Edition". DVD talk. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- Gilmore, Mikal (2012-09-27). "Bob Dylan Unleashed: A Wild Ride on His New LP and Striking Back at Critics". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- Gray, Michael (2006). The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Continuum International. ISBN 0-8264-6933-7.

- Hardy, Dominique (2006-08-29). "Tournage du film I'm Not There: Chambly en vedette". Journal de Chambly (in French). Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- Hedin, Benjamin (ed.) (2004). Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader. W.W.Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-32742-6.

- Heylin, Clinton (1996). Bob Dylan: A Life In Stolen Moments. Book Sales. ISBN 0-7119-5669-3.

- Heylin, Clinton (2003). Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades Revisited. Perennial Currents. ISBN 0-06-052569-X.

- Hoberman, J. (2007-11-13). "Like a Complete Unknown: I'm Not There and the Changing Face of Bob Dylan on Film". The Village Voice. Retrieved 2014-03-23.

- Lee, C.P. (2000). Like a Bullet of Light: The Films of Bob Dylan. Helter Skelter. ISBN 1-900924-06-4.

- Male, Andrew (2007-12-06). "Dylan Director Comes Clean". Mojo. Archived from the original on 2007-12-31. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

- McCarthy, Todd (2007-09-04). "Review: ‘I’m Not There’". Variety. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

- "Metacritic: 2007 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2008-01-02. Retrieved 2008-01-05.

- "Oscar Legacy: The 80th Academy Awards (2008) Nominees and Winners". The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- Pennebaker, D.A. (2006). Dont Look Back. New Video Group Inc. ISBN 0-7670-9157-4.

- Scott, A. O. (2007-11-21). "Another Side of Bob Dylan, and Another, and Another ...". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- Shelton, Robert (1986). No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan (2003 ed.). Da Copa Press. ISBN 0-306-81287-8.

- Sullivan, Robert (2007-10-07). "This Is Not a Bob Dylan Movie". New York Times. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- Unterberger, Richie (2007-02-26). "Interview with Joe Boyd". Richieunterberger.com. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- The Weinstein Company (2007-09-01). "I'm Not There: Production Notes". twcpublicity.com. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- Travers, Peter (2007-12-19). "Peter Travers' Best and Worst Movies of 2007: 9. I'm Not There". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2014-03-26.

See also

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: I'm Not There |

- I'm Not There at the Internet Movie Database

- I'm Not There at AllMovie

- I'm Not There at Box Office Mojo

- I'm Not There at Rotten Tomatoes

- I'm Not There - Metacritic

- Director Todd Haynes talks about I'm Not There at the 2007 New York Film Festival

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||