Hyperhidrosis

| Hyperhidrosis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | R61 |

| ICD-9 | 780.8 |

| OMIM | 144110 144100 |

| MedlinePlus | 007259 |

| eMedicine | topic list |

| Patient UK | Hyperhidrosis |

Hyperhidrosis is the condition characterized by abnormally increased sweating/perspiration,[1] in excess of that required for regulation of body temperature. It is associated with a significant quality of life burden from a psychological, emotional, and social perspective. As such, it has been referred to as the 'silent handicap'.[2]

The words diaphoresis and hidrosis both can mean either perspiration (in which sense they are synonymous with sweating[3][4]) or excessive perspiration (in which sense they can be either synonymous with hyperhidrosis or differentiable from it only by clinical criteria involved in narrow specialist senses of the words).

Classification

Hyperhidrosis can either be generalized or localized to specific parts of the body. Hands, feet, armpits, and the groin area are among the most active regions of perspiration due to the relatively high concentration of sweat glands. When excessive sweating is localized (e.g. palms, soles, face, underarms, scalp) it is referred to as primary or focal hyperhidrosis. Generalized or secondary hyperhidrosis usually involves the body as a whole and is the result of an underlying condition.

Hyperhidrosis can also be classified depending by onset, either congenital or acquired. Focal hyperhidrosis is found to start during adolescence or even before and seems to be inherited as an autosomal dominant genetic trait. Primary or focal hyperhidrosis must be distinguished from secondary hyperhidrosis, which can start at any point in life. The latter form may be due to a disorder of the thyroid or pituitary glands, diabetes mellitus, tumors, gout, menopause, certain drugs, or mercury poisoning.

Hyperhidrosis may also be divided into palmoplantar (symptomatic sweating of primarily the hands or feet), gustatory hyperhidrosis, generalized and focal hyperhidrosis.[1]

Alternatively, hyperhidrosis may be classified according to the amount of skin affected and its possible causes.[7] In this approach, excessive sweating in an area greater than 100 cm2 (16 in2) (up to generalized sweating of the entire body) is differentiated from sweating that affects only a small area.

Cause

The cause of primary hyperhidrosis is unknown, although some surgeons claim it is caused by sympathetic over-activity. Nervousness or excitement can exacerbate the situation for many sufferers. Other factors can play a role; certain foods and drinks, nicotine, caffeine, and smells can trigger a response.

Humectants such as glycerin, lecithin, and propylene glycol, draw water into the outer layer of skin. Glycerin, lecithin, and propylene glycol are found in Vaseline. Hypothetically excessive use of vaseline over time may be one cause of palmar hyperhidrosis, however research needs to be conducted to provide evidence.

A common complaint of patients is they get nervous because they sweat, then sweat more because they are nervous.

- Hyperhidrosis of a relatively large area (generalized; over 100 cm2)

- In people with a past history of spinal cord injuries

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Posttraumatic syringomyelia

- Associated with peripheral neuropathies

- Familial dysautonomia (Riley-Day syndrome)

- Congenital autonomic dysfunction with universal pain loss

- Exposure to cold, notably associated with cold-induced sweating syndrome

- Associated with probable brain lesions

- Episodic with hypothermia (Hines and Bannick syndrome)

- Episodic without hypothermia

- Olfactory

- Associated with intrathoracic neoplasms or lesions

- Associated with systemic medical problems

- Pheochromocytoma

- Parkinson's disease

- Thyrotoxicosis

- Diabetes mellitus

- Fibromyalgia

- Congestive heart failure

- Anxiety

- Menopausal state

- Due to drugs or poisoning

- Night sweats

- Compensatory

- Associated with toxins

- Infantile acrodynia induced by chronic low-dose mercury exposure, leading to elevated catecholamine accumulation and resulting in a clinical picture resembling pheochromocytoma.

- Hyperhidrosis of relatively small area (less than 100 cm2)

- Idiopathic unilateral circumscribed hyperhydrosis

- Reported association with:

- Blue rubber bleb nevus

- Glomus tumor

- POEMS syndrome

- Burning feet syndrome (Goplan's)

- Trench foot

- Causalgia

- Pachydermoperiostosis

- Pretibial myxedema

- Gustatory sweating associated with:

- Encephalitis

- Syringomyelia

- Diabetic neuropathies

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Parotitis

- Parotid abscesses

- Thoracic sympathectomy

- Auriculotemporal or Frey's syndrome

- Miscellaneous

- Lacrimal sweating (due to postganglionic sympathetic deficit, often seen in Raeder's syndrome)

- Harlequin syndrome

- Emotional hyperhidrosis

Treatment

Medications

Aluminium chloride is used in regular antiperspirants. However, hyperhydrosis sufferers need solutions or gels with a much higher concentration to effectively treat the symptoms of the condition. These antiperspirant solutions or hyperhydrosis gels are especially effective for treatment of axillary or underarm regions. Normally it takes around three to five days to see the results. The main secondary effect is irritation of the skin. For severe cases of plantar and palmar hyperhydrosis, there is some success using conservative measures such as higher strength aluminium chloride antiperspirants.[8] Treatment algorithms for hyperhidrosis recommend topical antiperspirants as the first line of therapy for hyperhidrosis. Both the International Hyperhidrosis Society (http://www.sweathelp.org) and the Canadian Hyperhidrosis Advisory Committee have published treatment guidelines for focal hyperhidrosis based on evidence based clinical support.

Injections of botulinum toxin type A, (Botox,[9] Dysport) are used to block neural control of sweat glands.[8][10] The effects can last from 3–9 months depending on the site of injections.[11] This procedure used for underarm sweating has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[12]

Prescription medications called anticholinergics, taken by mouth (orally), may be used to treat either generalized or focal hyperhidrosis.[13] Anticholinergics used for hyperhidrosis include propantheline, glycopyrronium bromide or glycopyrrolate, oxybutynin, methantheline, and benztropine. Use of these drugs can be limited, however, by the common side effects of the anticholinergic class—dry mouth, urinary retention, constipation, and visual disturbances such as mydriasis and cycloplegia. Additionally, many of the medications used to treat excessive sweating are not FDA approved for that purpose and are, rather, being used "off label." For people who find their hyperhidrosis is made worse by anxiety-provoking situations (public speaking, stage performances, special events such as weddings, etc.) and want temporary, short-term treatment for the duration of the event, an oral medication/anticholinergic can be of assistance. (Reference: Böni R. Generalized hyperhidrosis and its systemic treatment. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2002;30:44-47.)

Several anticholinergic drugs reduce hyperhidrosis. Oxybutynin (brand name Ditropan) is one that has shown promise,[8][14] although it has important side effects, which include drowsiness, visual symptoms and dryness in the mouth and other mucous membranes. A time release version of the drug is also available (Ditropan XL), with purportedly reduced effectiveness. Glycopyrrolate (Robinul) is another drug used on an off-label basis. The drug seems to be almost as effective as oxybutynin and has similar side-effects. Other anticholinergic agents that have tried to include propantheline bromide (Probanthine) and benztropine (Cogentin).

Surgical procedures

Sweat gland removal or destruction is one surgical option available for axillary hyperhydrosis. There are multiple methods for sweat gland removal or destruction such as sweat gland suction, retrodermal currettage, and axillary liposuction, Vaser, or Laser Sweat Ablation. Sweat gland suction is a technique adapted for liposuction.[15]

The other main surgical option is endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy (ETS), which cuts, burns, or clamps the thoracic ganglion on the main sympathetic chain that runs alongside the spine. Clamping is intended to permit the reversal of the procedure. ETS is generally considered a "safe, reproducible, and effective procedure and most patients are satisfied with the results of the surgery".[16] Satisfaction rates above 80% have been reported, and are higher for children.[17][18] The procedure causes relief of excessive hand sweating in about 85-95% of patients.[19] ETS may be helpful in treating axillary hyperhidrosis, facial blushing and facial sweating; however, patients with facial blushing and/or excessive facial sweating experience higher failure rates, and patients may be more likely to experience unwanted side effects.[20]

ETS side effects have been described as ranging from trivial to devastating.[21] The most common secondary effect of ETS is compensatory sweating, sweating in different areas than prior to the surgery. Major drawbacks related to compensatory sweating are seen in 20–80%.[22][23][24] Most people find the compensatory sweating to be tolerable while 1–51% claim that their quality of life decreased as a result of compensatory sweating."[17] Total body perspiration in response to heat has been reported to increase after sympathectomy.[25]

Additionally, the original sweating problem may recur due to nerve regeneration, sometimes within 6 months of the procedure.[22][23][26]

Other side effects include Horner's Syndrome (about 1%), gustatory sweating (less than 25%) and on occasion very dry hands (sandpaper hands).[27] Some patients have also been shown to experience a cardiac sympathetic denervation, which results in a 10% lowered heartbeat during both rest and exercise; leading to an impairment of the heart rate to workload relationship.[28]

Lumbar sympathectomy is a relatively new procedure aimed at those patients for whom endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy has not relieved excessive plantar (foot) sweating. With this procedure the sympathetic chain in the lumbar region is clipped or divided in order to relieve the severe or excessive foot sweating. The success rate is about 97% and the operation should be carried out only if patients first have tried other conservative measures.[29] This type of sympathectomy is no longer considered controversial in regards to hypotension and retrograde ejaculation.[30][31] The development of retrograde ejaculation, inability to maintain erection and hypertension as a result of this surgery appears to be rare to non-existent; journal articles describing the technique and case reports suggest that none of 18 men undergoing the procedure at two separate surgical units experienced sexual disability following surgery, while no mention is made of hypertension or sexual disabilities occurring in female patients.[30][31]

Percutaneous sympathectomy is a related minimally invasive procedure similar to the botulinum method, in which the nerve is blocked by an injection of phenol.[32] The procedure allows for temporary relief in most cases. Some medical professionals advocate the use of this more conservative procedure before the permanent surgical sympathectomy.

Non-surgical treatments

Iontophoresis was originally described in the 1950s, although the exact mode of action remains elusive.[33] The device is usually used for the hands and feet, but there has been a device created for the axillae (armpit) area and for the stump region of amputees. The affected area is placed in a device that has two pails of water with a conductor in each one. The hand or foot acts like a conductor between the positively- and negatively-charged pails. As the low current passes through the area, the minerals in the water clog the sweat glands, limiting the amount of sweat released. Some people have seen great results while others see no effect. Instructions for using iontophoresis devices will vary depending on the device used, but in general, patients sit with both hands or both feet, or one hand and one foot, immersed in shallow trays filled with tap water for a short period of time (20 to 40 minutes) while the device sends a mild electrical current through the water. The process is normally repeated every two to three days for ten sessions. Once the desired dryness has been achieved, patients are switched to a maintenance schedule, usually once per week to once every other week, depending on the individual. To maintain dryness, iontophoresis treatments should be conducted before sweating begins to return, or the process may need to be started all over again to obtain the desired dryness. (Reference: Anliker MD, Kreyden OP. Tap water iontophoresis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2002;30:48-56.) Iontophoresis with solutions containing glycopyrrolate (as opposed to tap water) can be used to treat more resistant cases. The device can be painful but pain is usually limited to areas where a patient has small pre-existing cuts, scratches, or hangnails. To prevent potential discomfort, these types of scratches and cuts on the surface of the skin should be covered with a thin layer of a Vaseline-type gel. (Reference: Levit F. Treatment of hyperhidrosis by tap water iontophoresis. Cutis. 1980;26:192-194.) Over time the body adjusts to the procedure. In a double-blind study of iontophoresis for the treatment of excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis) published in 1989, it took 2 weeks for 80% of palms to respond, and by 20 days 100% of hands, 78% of feet, and 75% of axillae (underarms) responded. Of the 24 sites (body parts) treated that had at least a 50% improvement in subjective sweating symptoms, there was a statistically significant decrease in mean sweat production after 1 month of treatment compared to controls. (Reference: Dahl JC, Glent-Madsen L. Treatment of hyperhidrosis manuum by tap water iontophoresis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1989;69:346-348) Sometimes, tap water in certain geographic locations may be too "soft" for iontophoresis to work. That is, it doesn't contain many minerals or electrolytes (tiny particles that help the electric current travel through the water and into the skin). Adding about a teaspoon of baking soda to the trays of water can rectify this. An additional option is to add a prescription class of medications called anticholinergics, in the form of a crushed tablet, to the water trays. Typically glycopyrrolate 2-mg tablets are used for this purpose.[34]

In 2011, the U.S. FDA approved an electromagnetic medical device for the treatment of underarm (axillary) hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating). The device is called miraDry (http://www.miradry.com). As of 2014, the hyperhidrosis treatment device is available in North America, Asia Pacific, and Europe. Treatment with this device is given in a physician's office and results in the thermolysis (destruction by heat) of the sweat glands beneath the underarm skin. A study by Drs. Chi-Ho Hong and Lupin on 31 patients showed 99% effectiveness in the treatment of underarm excessive sweating with sweat-reduction lasting at least 12 months.[35] Data also shows sweat gland necrosis [destruction] at 11 days after treatment and reduction of sweat glands 6 months after treatment. Further follow-up on these patients showed 100% efficacy and 100% patient satisfaction results at 18 months.[36] At two study sites in Canada, 31 patients were treated for underarm hyperhidrosis with the electromagnetic device. The patients received one to three treatment procedures, held two to three months apart. The study showed the treatments were 94% effective and that sweating was reduced an average of 82%.[37] A study published in the Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy in 2013 [38] showed that the handheld electromagnetic device was effective in treating both axillary (underarm) hyperhidrosis and axillary osmidrosis (foul-smelling sweat). As part of the study, 11 patients were treated with the electromagnetic device and then evaluated 7 months later for improvement of symptoms. At the follow-up, 83.3% of the underarms treated were determined to have experienced significant improvement in the hyperhidrosis disease severity. Among those underarms that had exhibited foul odor (osmidrosis), 93.8% showed good to excellent results. Treatment sessions are performed on an outpatient basis and typically take a total of one hour. Local anesthesia is used and patients can resume daily activities and return to work immediately. Patients are advised to wait a few days before exercise. Temporary swelling and discomfort in the treatment area post-treatment is expected, with an average duration of approximately one week. Some people experience mild to moderate edema under the arms that lasts about a week or two. Other transient effects can include the formation of papules or nodules and axillary hair loss. Altered sensation in the treatment area can last several months.[39]

Prognosis and impact

Hyperhidrosis can have physiological consequences such as cold and clammy hands, dehydration, and skin infections secondary to maceration of the skin. Hyperhidrosis can also have devastating emotional effects on one’s individual life.

Affected people are constantly aware of their condition and try to modify their lifestyle to accommodate this problem. This can be disabling in professional, academic and social life, causing embarrassments. Many routine tasks can result in a disproportionate level of sweating, which can be emotionally draining to these individuals.

Excessive sweating or focal hyperhidrosis of the hands interferes with many routine activities,[40] such as securely grasping objects. Some focal hyperhidrosis sufferers avoid situations where they will come into physical contact with others, such as greeting a person with a handshake. Hiding embarrassing sweat spots under the armpits limits the sufferers' arm movements and pose. In severe cases, shirts must be changed several times during the day and require additional showers both to remove sweat and control body odor issues or microbial problems such as acne, dandruff, or athlete's foot. Additionally, anxiety caused by self-consciousness to the sweating may aggravate the sweating. Excessive sweating of the feet makes it harder for patients to wear slide-on or open-toe shoes, as the feet slide around in the shoe because of sweat.

Some careers present challenges for hyperhidrosis sufferers. For example, careers that require the deft use of a knife may not be safely performed by people with excessive sweating of the hands. The risk of dehydration can limit the ability of some sufferers to function in extremely hot (especially if also humid) conditions.[41] Even the playing of musical instruments can be uncomfortable or difficult because of sweaty hands. There is a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving awareness of hyperhidrosis, its serious effects, scientific and medical research related to the condition, available treatments, and other support and resources available to people with the condition and their loved ones. This organization is called the International Hyperhidrosis Society (http://www.SweatHelp.org).

Epidemiology

Focal hyperhidrosis is estimated at 2.8% of the population of the United States.[40] It affects men and women equally, and most commonly occurs among people aged 25–64 years. Some may have been affected since early childhood.[40] About 30–50% have another family member afflicted, implying a genetic predisposition.[40]

In 2006, researchers of Saga University in Japan reported that primary palmar hyperhidrosis locus maps to 14q11.2–q13.[42]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. pp. 777–8. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ↑ Swartling, Carl et al. (2011). "Hyperhidros - det "tysta" handikappet". Läkartidningen (in Swedish) 108 (47): pp2428–2432.

- ↑ Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- ↑ Wolters Kluwer, Stedman's Medical Dictionary, Wolters Kluwer.

- ↑ Roberto de Menezes Lyra, Campos JR, Kang DW, Loureiro Mde P, Furian MB, Costa MG, Coelho Mde S; Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Torácica. (Nov 2008). "Guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of compensatory hyperhidrosis.". J Bras Pneumol. 34 (11): 967–77. PMID 19099105.

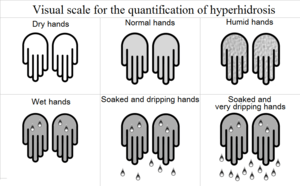

- ↑ Roberto de Menezes Lyra. (July–August 2013). "Visual scale for the quantification of hyperhidrosis.". J Bras Pneumol. 39 (4): 521–2. PMID 19099105.

- ↑ Freedberg, Irwin M.; Eisen, Arthur Z.; Wolff, Klaus; Austen, K. Frank; Goldsmith, Lowell A.; Katz, Stephen I., eds. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. p. 700. ISBN 978-0-07-138066-9.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Reisfeld, Rafael; Berliner, Karen I. (2008). "Evidence-Based Review of the Nonsurgical Management of Hyperhidrosis". Thoracic Surgery Clinics 18 (2): 157–66. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.01.004. PMID 18557589.

- ↑ http://www.botoxindubai.com/

- ↑ Ba, K O; Park, D M (1994). "Botulinum toxin and sweating". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 57 (11): 1437–8. doi:10.1136/jnnp.57.11.1437. PMC 1073208. PMID 7964832.

- ↑ Togel, B (2002). "Current therapeutic strategies for hyperhidrosis: a review". Eur J Dermatol 12 (3): 219–23. PMID 11978559.

- ↑ "Information for Healthcare Professionals: OnabotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Botox/Botox Cosmetic), AbobotulinumtoxinA (marketed as Dysport) and RimabotulinumtoxinB (marketed as Myobloc)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

- ↑ Togel B1, Greve B, Raulin C. (May–June 2002). "Current therapeutic strategies for hyperhidrosis: a review.". US National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health.

- ↑ Mijnhout, GS; Kloosterman, H; Simsek, S; Strack Van Schijndel, RJ; Netelenbos, JC (2006). "Oxybutynin: Dry days for patients with hyperhydrosis". The Netherlands journal of medicine 64 (9): 326–8. PMID 17057269.

- ↑ Bieniek, A; Białynicki-Birula, R; Baran, W; Kuniewska, B; Okulewicz-Gojlik, D; Szepietowski, JC (2005). "Surgical treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis with liposuction equipment: Risks and benefits". Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica 13 (4): 212–8. PMID 16356393.

- ↑ Henteleff, Harry J.; Kalavrouziotis, Dimitri (2008). "Evidence-Based Review of the Surgical Management of Hyperhidrosis". Thoracic Surgery Clinics 18 (2): 209–16. doi:10.1016/j.thorsurg.2008.01.008. PMID 18557593.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Steiner, Zvi; Cohen, Zahavi; Kleiner, Oleg; Matar, Ibrahim; Mogilner, Jorge (2007). "Do children tolerate thoracoscopic sympathectomy better than adults?". Pediatric Surgery International 24 (3): 343–7. doi:10.1007/s00383-007-2073-9. PMID 17999068.

- ↑ Dumont, Pascal; Denoyer, Alexandre; Robin, Patrick (2004). "Long-Term Results of Thoracoscopic Sympathectomy for Hyperhidrosis". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 78 (5): 1801–7. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.03.012. PMID 15511477.

- ↑ Prasad, A; Ali, M; Kaul, S (2010). "Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy for primary palmar hyperidrosis". Surgical endoscopy 24 (8): 1952–7. doi:10.1007/s00464-010-0885-5. PMID 20112111.

- ↑ Reisfeld, Rafael (2006). "Sympathectomy for hyperhydrosis: Should we place the clamps at T2–T3 or T3–T4?". Clinical Autonomic Research 16 (6): 384–9. doi:10.1007/s10286-006-0374-z. PMID 17083007.

- ↑ Schott, G D (1998). "Interrupting the sympathetic outflow in causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy". BMJ 316 (7134): 792–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7134.792. PMC 1112764. PMID 9549444.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gossot, Dominique; Galetta, Domenico; Pascal, Antoine; Debrosse, Denis; Caliandro, Raffaele; Girard, Philippe; Stern, Jean-Baptiste; Grunenwald, Dominique (2003). "Long-term results of endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy for upper limb hyperhidrosis". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 75 (4): 1075–9. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04657-X. PMID 12683540.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Yano, Motoki; Kiriyama, Masanobu; Fukai, Ichiro; Sasaki, Hidefumi; Kobayashi, Yoshihiro; Mizuno, Kotaro; Haneda, Hiroshi; Suzuki, Eriko et al. (2005). "Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy for palmar hyperhidrosis: Efficacy of T2 and T3 ganglion resection". Surgery 138 (1): 40–5. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2005.03.026. PMID 16003315.

- ↑ Boscardim, PC (2011). "Thoracic sympathectomy at the level of the fourth and fifth ribs for the treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis". J Bras. Pneumol. 37 (1): 6–12. PMID 21390426.

- ↑ Kopelman, Doron; Assalia, Ahmad; Ehrenreich, Marina; Ben-Amnon, Yuval; Bahous, Hany; Hashmonai, Moshe (2000). "The Effect of Upper Dorsal Thoracoscopic Sympathectomy on the Total Amount of Body Perspiration". Surgery Today 30 (12): 1089–92. doi:10.1007/s005950070006. PMID 11193740.

- ↑ Walles, T.; Somuncuoglu, G.; Steger, V.; Veit, S.; Friedel, G. (2008). "Long-term efficiency of endoscopic thoracic sympathicotomy: Survey 10 years after surgery". Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery 8 (1): 54–7. doi:10.1510/icvts.2008.185314. PMID 18826967.

- ↑ Fredman, B (2000). "Video-assisted transthoracic sympathectomy in the treatment of primary hyperhidrosis: friend or foe?". Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 10 (4): 226–9. PMID 10961751.

- ↑ Abraham, P; Picquet, J; Bickert, S; Papon, X; Jousset, Y; Saumet, JL; Enon, B (2001). "Infra-stellate upper thoracic sympathectomy results in a relative bradycardia during exercise, irrespective of the operated side". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery 20 (6): 1095–100. doi:10.1016/S1010-7940(01)01002-8. PMID 11717010.

- ↑ Reisfeld, Rafael (2008-05-04). "Lumbar Sympathectomy". Retrieved 2008-05-04.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Rieger, R.; Pedevilla, S. (2006). "Retroperitoneoscopic lumbar sympathectomy for the treatment of plantar hyperhidrosis: Technique and preliminary findings". Surgical Endoscopy 21 (1): 129–35. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0690-8. PMID 16960674.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Reisfeld, Rafael (2011-02-11). "Lumbar Sympathectomy with Clamping Method Paper". Retrieved 2011-02-11.

- ↑ Wang, Yeou-Chih; Wei, Shan-Hua; Sun, Ming-Hsi; Lin, Chi-Wen (2001). "A New Mode of Percutaneous Upper Thoracic Phenol Sympathicolysis: Report of 50 Cases". Neurosurgery 49 (3): 628–34; discussion 634–6. doi:10.1097/00006123-200109000-00017. PMID 11523673.

- ↑ Kreyden, Oliver P (2004). "Iontophoresis for palmoplantar hyperhidrosis". Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 3 (4): 211–4. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00126.x. PMID 17166108.

- ↑ P. Stolman, Lewis (October 1998). "Treatment of Hyperhidrosis" (PDF). Dermatologic Clinics.

- ↑ Hong HC, Lupin M, O'Shaughnessy KF. Clinical evaluation of a microwave device for treating axillary hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg. 2012; 38:728-735, http://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/Hong%20study%20%282012%29%20.pdf

- ↑ Lupin M, Hong HC-H, O'Shaughnessy KF. Long-term evaluation of microwave treatment for axillary hyperhidrosis. Lasers Surg Med. 2012; 44:6, http://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/Lupin_Microwave_Treatment_%20FollowUp.pdf

- ↑ http://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/Evaluation_miraDry_Lupin.pdf

- ↑ Lee SJ et al. "The efficacy of a microwave device for treating axillary hyperhidro... - PubMed - NCBI".

- ↑ http://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/Lupin_Microwave_Treatment_%20FollowUp.pdf and http://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/Hong%20study%20%282012%29%20.pdf

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Haider, A.; Solish, N (2005). "Focal hyperhidrosis: Diagnosis and management". Canadian Medical Association Journal 172 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040708. PMC 543948. PMID 15632408.

- ↑ http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/473206_2[]

- ↑ Higashimoto, Ikuyo; Yoshiura, Koh-Ichiro; Hirakawa, Naomi; Higashimoto, Ken; Soejima, Hidenobu; Totoki, Tadahide; Mukai, Tsunehiro; Niikawa, Norio (2006). "Primary palmar hyperhidrosis locus maps to 14q11.2-q13". American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 140A (6): 567–72. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.31127. PMID 16470694.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

- ↑ "Glycerin Topical". WebMD. (2014)www.webmd.com/drugs/2/drug-20275/glycerin-top/details.